Vrindavan, Jaipur & New Delhi: A constant stream of devotees shuffle through the narrow lanes of Vrindavan, Uttar Pradesh, to reach the Shri Banke Bihari Temple. A bespectacled college student films the crowd, keeping up an excited live commentary for his followers. A newlywed couple confers quietly with a saffron-robed sadhu. Shops lining the street do brisk trade in everything from Krishna idols and diyas to jalebis and kachoris.

India’s pilgrimage business is booming. And it’s not just old people who are launching off on temple tourism. Young Indians are swarming places of worship in droves, with Hindu revivalism and Instagram Reels in mind.

“I think it’s our responsibility to undertake pilgrimages once in our life, especially since calamities around the world have increased,” said Devatar Roy, a law student from Assam, explaining the meteoric rise of devotees in the temple town. “Our dharma, our culture — it is important to see that with our eyes.”

Religious tourism in India is undergoing a renaissance. Once seen as the preserve of pensioners or the devout poor, pilgrimage travel has gone mainstream. College students, middle-class families, and high-end travellers alike are scrambling to book temple-centric trips, from Kedarnath in Uttarakhand to Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu.

A post-Covid reality check and pivot toward faith, government-led temple-infrastructure development and better access to pilgrimage cities is redefining India’s tourism sector. For long, ‘tourism push’ meant wooing foreigners to the Taj Mahal, Jaisalmer, and Palace on Wheels. In Modi’s decade, the priority has shifted to the domestic base. And it shows in the budget allocations too.

The domestic numbers are adding up. According to the Uttar Pradesh Department of Tourism, 65 million domestic tourists visited Mathura-Vrindavan in 2022–23, second only to Varanasi. That’s over eight times the number of domestic tourists Goa received that year. And it’s not just UP. A KPMG report noted that over 1.4 billion domestic tourists visited pilgrimage sites across India in 2022, up from 677 million in 2021.

In parallel, foreign tourists coming into India is slowly rebounding to pre-pandemic levels, but still falling far short of its potential. The government doesn’t seem particularly concerned either. Ministry of Tourism data shows that over the past five years, the marketing budget for promoting foreign travel has been slashed drastically from Rs 524 crore in 2021–22 to just Rs 3 crore in 2025–26 for the flagship ‘Incredible India’ campaign — a 99 per cent cut. By contrast, Rs 137 crore has been allocated to boost domestic tourism.

We have seen a decline in [foreign] tourists. If not in footfall, then definitely in terms of revenue. India has become expensive. Now mainly budget travellers come here

-Ashok Jain , art & handicrafts shop proprietor in Agra

“We have great potential as a destination — world heritage sites, food, culture, iconic hotels and beautiful experiences,” said Dipak Deva, managing director of Sita World Travel, an agency that focuses on inbound tourism. “The problem is we are not telling the world about India. There is no money being spent by the government on the Incredible India campaign.”

Despite the lack of support, India recorded 9.52 million Foreign Tourist Arrivals (FTAs) in 2023—a 48 per cent jump from 6.44 million in 2022, inching closer to the pre-pandemic high of 10.93 million in 2019. Provisional data for 2024 suggests a further uptick, with 9.66 million FTAs.

This rebound came even as the government scaled down its foreign tourism machinery. On 13 March 2023, then tourism minister G Kishan Reddy told the Lok Sabha that only six of 31 overseas tourism posts had been filled. He also said the ministry planned to shut all overseas tourism offices by the end of that month. The Ministry of Tourism currently has no foreign offices listed on its website.

In recent years, as India’s pollution and women’s safety problems have made international headlines, foreign tourist arrivals have been less than impressive. Many Indians reacted with what appeared to be a shrug.

Meanwhile, the Indian government has turned its attention inward. Schemes like the Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual Augmentation Drive (PRASHAD) have identified destinations such as Guruvayur Temple in Kerala, Nada Saheb Gurudwara in Haryana and Ambaji Temple in Gujarat for infrastructure upgrades.

Since the scheme’s launch in 2015, Rs 1,647 crore has been sanctioned across 48 projects, with Rs 1,037 crore disbursed. But projects aren’t just limited to temples. In Varanasi, for instance, Rs 9 crore was sanctioned for river cruise tourism.

“The traditional, high-density temple towns like Shirdi (Maharashtra) and Tirupati (Andhra Pradesh) remain all-time hits,” said Neeraj Singh Dev, executive vice president at Thomas Cook & SOTC, prominent international travel agencies. “But apart from them, you see these new religious circuits coming up with an inventory of hotels, direct connectivity between metro and non-metro cities. That is really boosting travel in this space.”

The dual impact of the pandemic and access to religious content cannot be understated, according to Seshadri Chari, an RSS member who also serves on the BJP’s National Executive Committee.

Also Read: Braj is new launchpad for religious influencers—Gopi glam, dance reels, temple tours

Spiritual sojourns, with a Sangh push

Large, colourful murals of Lord Krishna greet visitors at the entrance of Vrindavan’s Tourist Facilitation Centre. Built for Rs 9.36 crore under the PRASHAD scheme, the centre is part of the government’s ongoing temple-town makeover.

“Ever since the Covid-19 pandemic, this centre has seen a large increase in the number of tourists,” said Kuldeep Dixit, 38, a Vrindavan resident who manages the facility. “Of course, demand is also seasonal. Bengalis come here during Holi. Gujaratis visit between January and February.”

In the peak May heat, the centre offers a welcome refuge to pilgrims. The main hall is packed with pilgrims stretched out on mats or mattresses. Dormitory beds and non-AC rooms go for as little as Rs 50 to Rs 200 a night, making it one of the few affordable options for lower income travellers, mostly farmers and daily-wage labourers.

Sprawled on a mat near a cluster of chairs, a group of farmers from Indore, Madhya Pradesh, sit cross-legged and discuss their itinerary for the day. They have stopped by Vrindavan on their way to the Char Dham Yatra. This year, they have free time to travel.

“Rainfall was low this year and labour is in short supply,” said Mahesh Gujar, 55, who grows soyabean, onions, wheat, and potatoes. “Pollution from the industrial area has also affected this year’s output, so we thought now is a good time to undertake the Char Dham.”

But Gujar was quick to clarify that faith was the primary driver of his travels. He proudly rattled off previous pilgrimages, from Mount Abu to Haridwar and Vaishno Devi.

“Hindus have finally opened their eyes. We have been guided by the teachings of Pradeep Mishra ji,” he said, referring to a Madhya Pradesh-based spiritual leader. He’s among the country’s innumerable spiritual and religious leaders, many of whom have large followings and exert significant influence.

As paap (sins) is increasing, punya (virtue) is also increasing. To balance the rise in sins, more people are visiting temples

-Hariom Khandelwal, visitor to Vrindavan from Bengaluru

Mishra has over 8 million subscribers on YouTube, where he posts his speeches and sermons. His digital following skyrocketed during the pandemic, when smartphones became both temple and television. Influenced by such figures, many like Gujar are undertaking pilgrimages with renewed vigour.

Vrindavan has its own share of spiritual gurus. Thousands arrive daily to visit Premanand Govind Sharan (Premanand Ji Maharaj) at his ashram in the temple town. Former Indian cricket captain Virat Kohli added to the buzz after visiting the ashram multiple times, most recently a day after announcing his retirement.

The dual impact of the pandemic and access to religious content cannot be understated, according to Seshadri Chari, an Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) member who also serves on the BJP’s National Executive Committee. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), he said, are actively recruiting sanyasis and sadhus so that ‘Hindu unity is achieved’.

“If I tell you to quit smoking, you may not listen to me. But if the same advice is coming from a religious leader you follow, no matter the size of their following, you tend to listen,” added Chari.

This, he noted, was the same technique used by VHP in the Ram Janmabhoomi movement for garnering support. Although the movement was rooted in Ayodhya, smaller temples across the country were brought into the fray. People in remote towns and villages felt part of something bigger that they connected to on a spiritual level.

“There was a programme called Ram Shila, where you worshiped a brick inscribed with ‘Shri Ram’ at your local temple, which was then used in the construction of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya,” said Chari. “Because the Sangh Parivar has a great footprint across the country, there was a function across each and every village.”

As access improves, the range of travellers is growing more diverse — from young, tech-savvy devotees embracing a renewed sense of religiosity to high-net-worth individuals seeking spiritual journeys without compromising on comfort.

Youthful devout fervour meets 5G

The increase in religiosity is not just limited to the elderly. During the pandemic, young people with smartphones, unlimited data, and free time turned to YouTube, Instagram, and other social media platforms to access religious content.

“In my days, we would go to temple only during the time of examinations,” said Chari, laughing. “Now, so many students I know went to the Kumbh Mela this year.”

When he asked why, he said his students cited the “star alignment once in 144 years”. Surprised, Chari asked them whether they believed that. But to them, belief was irrelevant — the opportunity to experience this kind of event was a once in a lifetime opportunity.

That impulse— to explore religious identity — coursed through the crowds outside the temples in Mathura and Vrindavan.

At Shri Krishna Janmasthan temple, young pilgrims, newly married couples and groups of friends smiled as they took in the environment. Some spoke of realising life’s fragility during the pandemic, others of dharma, karma, and making amends.

“In Kaliyuga, only by remembering the name of God can one break the cycle of birth and death,” said Pandit Sanjiv Punetha, a sales officer at a dairy company, standing outside a food stall. “Earlier, there was misinformation spread by opponents of our Sanatan Dharma, due to which the public was misguided. But now the saints and scholars of our religion have reclaimed our identity.”

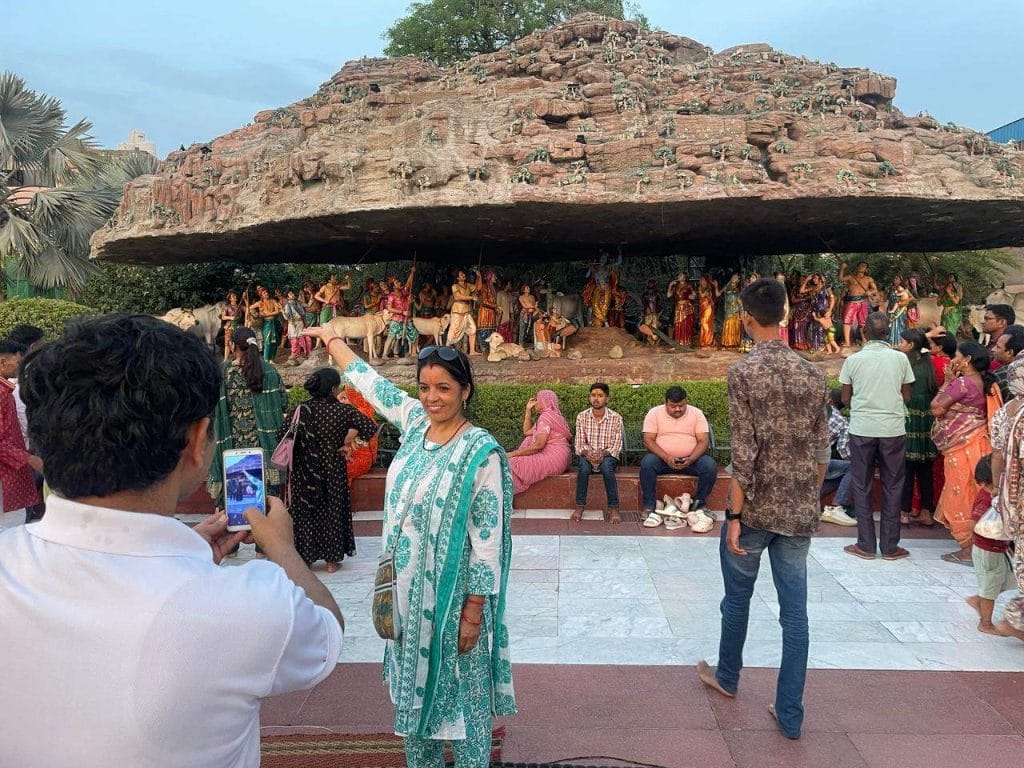

Outside Prem Mandir, thousands streamed through the gates, pausing for photos in front of the elaborate religious installations. The most popular: Lord Krishna dancing on the giant serpent Kaliya Naag. Religious devotion and selfies went hand in hand.

“As paap (sins) is increasing, punya (virtue) is also increasing,” said Hariom Khandelwal, 33, from Bengaluru, who was visiting the temple for a second time. “To balance the rise in sins, more people are visiting temples.”

Until relatively recently, the desire to visit temples largely remained unfulfilled without adequate facilities.

Recognising this, the government accelerated infrastructure development at pilgrimage sites. Improved road networks, new airports, cleaner temple surroundings, and the growth of online travel bookings have made these destinations more accessible than ever before.

What has changed from the past is that you have more people from the upper middle class and HNIs travelling for pilgrimages. This is down to increased connectivity of flights, better infrastructure and the opening up of four and five-star hotels

-Neeraj Singh Dev, executive vice-president, Thomas Cook & SOTC

In January 2024, ahead of the Ram Temple inauguration, Prime Minister Narendra Modi took part in a cleaning drive at the Kalaram temple complex in Nashik, Maharashtra. The symbolic gesture was aimed at promoting the government’s Swachh Bharat Mission, with Modi urging the country’s youth to take up temple cleanliness drives.

“The dirt and squalor at temples can really put you off. But I went to the Padmanabhaswamy temple in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, and it was wonderfully maintained,” said Chari, adding that even the washrooms were impressive. “Much better than the ones at Patna airport, where I am sitting right now.”

As access improves, the range of travellers is growing more diverse — from young, tech-savvy devotees embracing a renewed sense of religiosity to high-net-worth individuals seeking spiritual journeys without compromising on comfort.

Pilgrimage gets the 5-star touch

At the Jaipur office of SOTC for Holidays, bright yellow posters advertising travel to Australia, South Africa, and Europe entice customers with deep pockets. But the bestseller is closer to home: the ‘Char Dham Yatra by Helicopter’ package. Bookings are sold out for May and most of June. The premiumisation of religious tourism has arrived.

“Most of our customers are looking for comfort,” said Vikas Bisht, a deputy manager at SOTC, adding that these packages primarily cater to senior citizens. “We provide helicopters from point to point. Without this you would have to walk for hours.”

The Rs 2.2 lakh-per-person package covers five nights of stay, all meals, and helicopter transport to the four pilgrimage sites in Uttarakhand — Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath.

Another major draw is the offer of VIP darshans, a kind of legitimised cheat code that lets pilgrims bypass long queues. What were earlier seen as roadblocks by the rich are now being circumvented by hefty fees.

“What has changed from the past is that you have more people from the upper middle class and HNIs [High Net Worth Individuals] traveling for pilgrimages,” said Neeraj Singh Dev of Thomas Cook & SOTC. “This is down to increased connectivity of flights, better infrastructure and the opening up of four and five-star hotels.”

His company’s focus is now squarely on the high-end market. The old-school train and dharamshala model is no longer the default. Instead, there are sub-brands for luxury religious travel.

SOTC’s Darshans and Thomas Cook’s Spiritual Journey offer tailor-made experiences for customers who want to skip temple lines, avoid long train journeys, and live in high-end comfort. Four-night per person packages, excluding flights, range from Rs 25,800 for the Rath Yatra in Odisha to Rs. 27,500 for a temple tour around Tamil Nadu.

“This is the wave we are riding on,” said Dev, adding that pilgrimage travel has been on a roll over the last three years. Events like the Maha Kumbh Mela and the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya have catapulted the concept to new heights. “A new Golden Religious Triangle — Kashi, Prayagraj and Ayodhya — has become hugely popular.”

Luxury hotels are taking notice. In May 2024, Marriott opened its 150th hotel in India at Katra, overlooking the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine and offering guests an alcohol-free, vegetarian-only environment. A year earlier, the international chain opened a hotel in Varanasi. In 2019, Indian Hotels Company Limited (IHCL) opened a Dravidian architecture-inspired Taj hotel in Tirupati. Five-star hotel brands like Taj, Oberoi and Trident already have projects underway in Ayodhya.

Even at this year’s Maha Kumbh Mela — for decades seen as a pilgrimage for the poor — wealthy Indians enjoyed the comfort of a VIP experience. A five-star tent city was constructed, complete with luxury tents, helicopter rides and private access to the Sangam area.

“We stayed at one of the IRCTC tents at the Kumbh Mela and it was only 500 meters from the main Sangam,” said Anita Shivdasani, a Mumbai-based garment exporter, who paid Rs 22,000 for two people. She also visited Kedarnath by a glass-floored helicopter, describing it as an unforgettable experience.

“I wouldn’t have gone without these arrangements,” she added.

New money in old temple towns

Whatever the hour, there’s a pilgrim takeover on the benches and pavements outside Vrindavan’s Prem Mandir. Though temples remain shut from noon to 5 pm, the shops and restaurants that have sprouted around them are always busy catering to devotees.

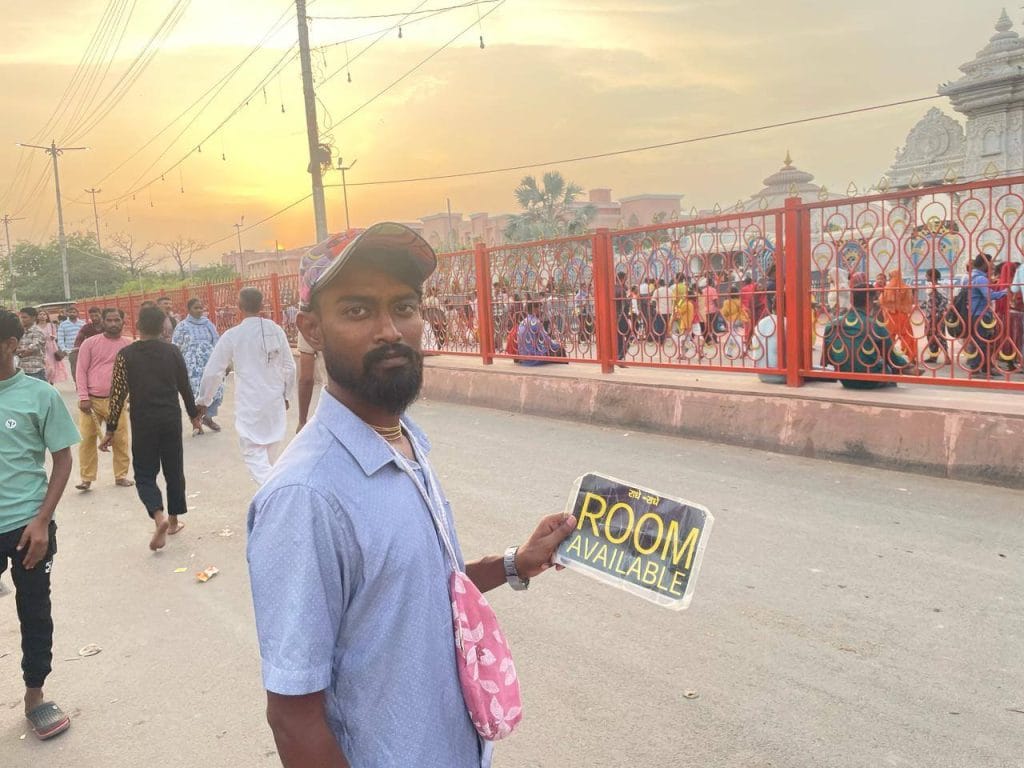

The pilgrimage boom has answered prayers for economic opportunities. Touts scuttle through the crowds with large ‘Rooms Available’ signs. Street vendors sell peacock feathers and some specialise in painting foreheads with vermillion.

Big brands aren’t passing up on the opportunity either.

Fifty metres down the road from Prem Mandir, restaurant chain Bikanervala offers a fully air-conditioned dining experience for pilgrims with a little more to spend. The floor above is occupied by Hotel Prem Inn, one of the many budget hotels that have come up.

“Most weekends we are completely booked,” said Suraj Sharma, 23, a receptionist at Hotel Prem Inn. As a Vrindavan resident, Sharma has seen the shifting tide of business in his hometown, which he says is mostly from the National Capital Region.

He too said Covid-19 changed the tourist profile. It forced even the young to confront their own mortality.

“Younger people would think they would earn first and go on pilgrimages later in life. But during the pandemic, even young people died,” said Sharma. “Now, younger people are travelling in small groups, visiting a few places on the same trip, and worrying about earning later.”

Multigenerational trips are on the rise as well, according to Dev, with more children in their 30s and 40s taking their parents on religious tours.

“These trips are so convenient now that multigenerational families are able to travel together,” said Dev. “We saw tons of young people taking their parents to the Golden Temple in Amritsar and for the Maha Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj.”

Even outside the premium segment, temple towns are full of families. Outside Prem Mandir, fathers ferry their children on tired shoulders, mothers carry bags filled with snacks, and grandparents snap pictures. Many have swapped expensive hill stations for religious destinations.

Within the Shree Krishna Janmabhoomi Temple complex in Mathura, the shops sell everything from golden diyas and miniature idols to toy guns and kitchen sets. Nakul Chauhan, 44, whose father opened their store in 1978, said business has changed over the last three years. Not only are there more visitors, according to him, they are coming for different reasons— not just faith but leisure.

“After the pandemic, social media reels highlighted all these pilgrimage sites,” said Chauhan. “This has led to an increase in visitors, and of course my business.” Most of the items sold at his shop have some connection to the temple — a yellow Lord Krishna kurta, items for pooja path (prayers), tiny replicas of the temple.

Across from his shop, a Tamil Nadu tour group is herded around the complex by a guide. According to Dev, distance shapes duration. They seem determined to take in every detail.

“The longer the distance they come from, the longer the trip they do,” said Dev, adding that if people are coming all the way from South India, they tend to mix sightseeing with temple visits. “Someone from Kerala visiting the Golden Temple in Amritsar will extend their trip to include Dharamshala as well, for the leisure part.”

But even as temple towns thrive, India’s traditional tourist hubs are going through a churn.

Weddings in, foreigners out?

At Kalakriti, an arts and culture store in Agra, proprietor Ashok Jain is doling out instructions to his craftsmen in the middle of the display area. Taj Mahal-inspired marble bowls, wooden chess sets, and intricate silk carpets take up space on the shelves. The halls of the store, once visited by Hollywood actress Julia Roberts and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, are devoid of any foreign tourists.

“We have seen a decline in tourists. If not in footfall, then definitely in terms of revenue,” said Jain, whose store’s façade is inspired by Mughal architecture. “India has become expensive. Now mainly budget travellers come here.”

Jain and his colleague, Sonal Sethi, lamented on how an increase in hotel prices and lack of amenities has driven down foreign tourism in Agra. The Kalakriti auditorium is home to the world’s largest replica of the Taj Mahal, but increasingly its seats are lying vacant.

“Around 70 per cent of a tourist’s expenses go towards hotel accommodation,” said Jain, adding that the remaining 30 per cent goes towards transportation, guides, shopping, and food. “Only 12 per cent goes towards miscellaneous expenses. And this has a direct impact on us.”

Tour operators have felt the impact. At the parking lot of Touraids (i), a travel agency down the road from Kalakriti, over two dozen tourist vehicles lie idle. General manager Mahatim Singh sits in an office right opposite, in a non-descript warehouse where he leads operations.

Singh explained that the decline in foreigners isn’t down to one single factor. War between Russia and Ukraine, the rising cost of living in Europe, and other countries promoting domestic travel have all led to a decline in inbound tourists. But he ascribes most blame to India’s own hospitality sector.

“It’s the dynamic pricing of hotels that brings uncertainty to foreign tourists,” said Singh, referring to the four- and five-star luxury hotels with a national presence. “There is no consistency. Tourists will inquire about prices and a few days later, these same hotels will jack up the rates.”

These hotels aren’t too worried, according to him. They’ve found more alternative revenue streams. Destination weddings and corporate events have become their new cash cows.

“They earn high margins on weddings. Then there’s a new segmentation they have discovered called MICE (meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions),” said Singh. “That’s why now, you have more budget travellers coming to India.”

Domestically, luxury hotels have become the domain of high-end destination weddings, from Jaipur and Udaipur to Goa. Places that were largely frequented by foreign tourists are now hosting some of the most glamorous Indian nuptials.

“Earlier weddings were about large numbers, but in the last five years, the rise of luxury destination weddings with a slightly smaller crowd is a lot more,” said Nitya Bagri, founder of A New Knot, a wedding planning company. “We organise 11-12 weddings every season (Nov – Feb), of which around 8 are in Rajasthan.” said Nitya Bagri, founder of A New Knot, a wedding planning company. Most hotels require a buyout of the entire properly, she added, so the venue is exclusively for the wedding.

Instead of relaxing, I was always on guard, worried I would be overcharged or misled. It’s a shame, because India is beautiful and has so much to offer. But after that experience, I’ve found myself avoiding it for vacations

-Samuel T, a New York resident who visited Delhi and Mumbai

There aren’t many properties that can handle her clients’ demands, according to Bagri. But hotel chains are catching up. Udaipur, for one, added four new luxury hotels in the past year—including a Taj, ITC and Fairmont—primarily to accommodate weddings, she said.

“We have struggled in securing hotel space for the luxury end due to large domestic wedding blocks,” said Jamshyd Sethna, founder of Banyan Tours, a luxury travel agency. “It’s easy money for the hotels, though a huge negative impact on service standards and food and beverage quality.”

Despite these challenges, Sethna says luxury tourism isn’t on the decline. In the first year after the pandemic, his company made a 70 per cent revenue recovery. By the second year, they were 15 per cent higher than even pre-pandemic levels.

A report by Booking.com, How India Travels 2024, corroborates Sethna’s experience. India recorded a 17 per cent year-on-year growth in luxury accommodation, with 39 per cent of travellers opting for five-star hotels.

But not every foreign tourist walks away impressed. Their experience doesn’t end with the marble floors and gilded walls of high-end hotels. And often, the reality outside the hotel doesn’t measure up.

India’s foreign exchange earnings through tourism in 2024 were estimated at US$ 33.18 billion, an 18 per cent increase over the previous year. But tour operators argue that India is losing big-spending tourists to destinations like Thailand and Vietnam.

An unwelcoming experience

Luxury hotels are just the tip of the opaque pricing iceberg. For Samuel M, a 34-year-old New York resident, what was meant to be a week of “pure relaxation” in India last year turned into a nightmare of haggling and headaches.

“From the moment I landed in Delhi, it felt like I had to be on high alert,” he said. “The first hiccup was with my Uber from the airport.” The app showed a fixed price, but the driver demanded ‘extra traffic charges’ at drop-off. “It wasn’t a huge amount, but it set the tone.”

This was just the start of a harrowing set of experiences for the American citizen. He called up his next hotel, in Mumbai, for room rate confirmation but was quoted a different price than what his Indian friend was given.

“This was enough to make me feel uneasy and, honestly, a bit unwelcome,” he said, adding that throughout his stay, he found himself constantly double-checking bills, negotiating with drivers, and second-guessing every offer.

Being overcharged for everyday services isn’t new for foreign visitors in India. What’s worrying, say tour operators, is how this has percolated into the formal travel sector. It raises questions about the country’s ability to attract tourists or draw return visitors.

“Instead of relaxing, I was always on guard, worried I would be overcharged or misled,” said Samuel, who is married to an NRI. “It’s a shame, because India is beautiful and has so much to offer. But after that experience, I’ve found myself avoiding it for vacations.”

Visiting India for a college friend’s wedding, 27-year-old Kate Blasco from USA lamented on the infrastructure challenges she faced during her nine-day trip. Like the millions of tourists who find it difficult to navigate the nation’s roads and traffic, Blasco wasn’t spared either.

“There aren’t many marked sidewalks or streetlights, so we often would find ourselves trying to cross the street and we were in the middle of a very busy road,” she said, adding that they had to dodge vehicles or find lulls in the flow of traffic to dart across. “Doing this while also taking care of your belongings is nearly impossible.”

Delhi’s infamous high AQI (Air Quality Index) cast another pall.

“When we first landed, the AQI was in the high 300s,” she said. “I was concerned about how exposure for even a couple of days could impact how I was feeling. Something that gave me pause was deciding whether we should do indoor activities versus going outside and exploring the city.”

Foreign tourist arrivals may be recovering, but many visitors leave disillusioned. Cultural heritage alone cannot sustain the sector. Pricing opacity, poor infrastructure, and environmental degradation remain serious obstacles to becoming a top destination.

The Indian government faces a double challenge: keeping up the momentum in domestic religious tourism while also enticing foreign travellers who are willing to spend.

Also Read: Indian weddings get a new destination in tier-2 cities—Rishikesh, Khajuraho, Corbett

Rise in budget tourists, not big spenders

Smoking a cigarette on the veranda of Moustache Hostel in Jaipur, 34-year-old Tim Fournier is on the last leg of his solo trip around India. The Swiss national flew into Delhi, saw the Taj Mahal in Agra, relaxed on Goa’s beaches, and ended with a flight to Jaipur.

India is increasingly seeing budget and solo travellers. According to Booking.com’s 2024 report, 35 per cent of tourists are choosing one- and two-star hotels, with hostels and service apartments growing in popularity.

“I was fascinated by the history of the country,” Fournier said, after taking a sip of his beer. “My girlfriend never wanted to come here, so after we broke up, I booked a flight.”

The hostel he is staying at charges between Rs 400 to Rs 1,000 per night. For Fournier, apart from airfare, the entire trip was affordable.

Back home, his work as a chef and ski instructor provided enough savings for an international trip to India, but fell short for a comfortable vacation around Europe.

“Everyone told me the country is a bit dirty and you need to get vaccines. But I’m not shocked, it’s a lot like Thailand,” he said, adding that one of his friends is married to an Indian, so he knew what to expect. “She told me you are either going to love it or hate it.”

Low-cost hostels are sprouting up across the country, especially in popular destinations like Delhi, Jaipur, and Agra. In Paharganj, just outside New Delhi Railway Station, a cluster of hostels caters to the budget traveller.

At the front desk of the Paharganj Zostel, a popular hostel chain with properties across India, the receptionist said that over the last three years, they have consistently been getting foreigners during the October to March peak season.

But for Deva, this isn’t the ideal tourist for India. He wants people to come to the country and spend serious money.

“I don’t believe in guest numbers. I believe in tourism revenue,” he said. “At the end of the day, this is what is advantageous to the host country.” He pointed to Kotor in Montenegro as a cautionary tale: “Tourists get off the cruise, walk around the city and don’t even spend ten dollars.”

India’s foreign exchange earnings through tourism in 2024 were estimated at US$ 33.18 billion, an 18 per cent increase over the previous year. But tour operators argue that India is losing big-spending tourists to destinations like Thailand and Vietnam. In 2024, Bangkok became the most visited tourist destination in the world, with 32.4 million visitors.

“Tourism is the only export where there can’t be any tariffs,” said Deva, referencing US President Donald Trump’s tax hikes on Indian textiles, automobiles, and pharma. “Every dollar an international visitor spends on hotels, airlines, guides, local crafts and food is hard foreign exchange credited directly to our balance of payments.”

The Indian government faces a double challenge: keeping up the momentum in domestic religious tourism while also enticing foreign travellers who are willing to spend. Luxury hotels, focused on weddings and events, may not lead that effort. For now, it’s budget and solo travellers who continue to check into hostels like Blue Beds in Jaipur.

“Look, I’ve seen no downward trend amongst budget travellers coming to our hostel,” said Anuj, the receptionist at Blue Beds. “But a few foreigners did decide to go to the Kumbh Mela this year.”

Udit Hinduja is a graduate from the inaugural batch of ThePrint School of Journalism.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)