New Delhi: The three-foot-long, 12th-century sculpture Parrot Lady had a special message for visitors at the ‘Return of Treasures’ exhibition in Khajuraho last year.

“You are viewing me in this exhibition not only as a nayaka [leading lady] but also as a previous victim of illicit trafficking, stolen and forcibly taken far away from my home,” read the text label.

The sculpture was finally returned to India from Canada in 2015, where it had been in the hands of an art collector who’d bought it on eBay. Its repatriation was part of Narendra Modi’s prestigious and aggressive drive to recover trafficked artefacts. Since 2014, a whopping 640 stolen antiquities have been brought back to India, compared to only 13 retrieved between 1947 and 2014.

Each object’s return is celebrated and wrapped in triumphant headlines. But their afterlife in India reveals a more complex story of both revival and roadblocks. These artefacts offer lessons in national pride, worship rituals, and historical research. Yet there are also questions around inadequate documentation, limited public access, and a gap between repatriation and actual reinstatement in their original sites.

For years, Western museums and governments have been reluctant to return objects to poorer nations, citing concerns about safekeeping. In India, the reality is mixed.

On the upside, some objects are having a spectacular rebirth, with new lives in exhibitions, museums, and even temple sanctuaries.

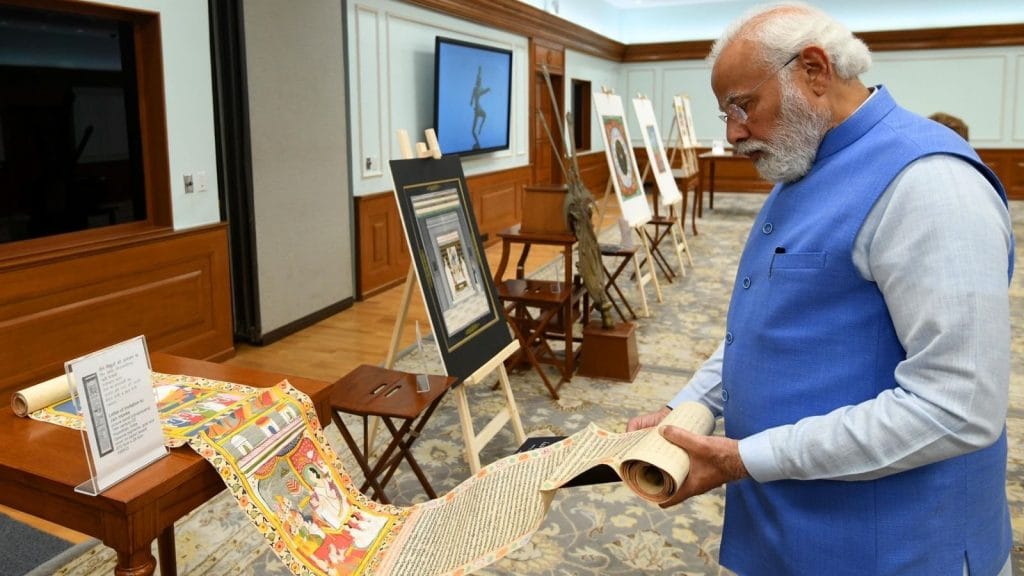

After Khajuraho, the G20 summit in Delhi hosted another exhibition of repatriated treasures. Among the stars of the show were the 12th-century Dancing Ganesha and the 11th-century marble Brahma-Brahmani, displayed in a section titled ‘Glimpses of Return’. Each artefact came with detailed information, complete with place of origin and unique accession number.

The retrieved antiquities span centuries and continents. The 10th-century green chlorite Durga Mahishamardini came from a museum in Stuttgart, the Kushana-era Seated Buddha from the National Gallery of Australia, and an 8th-century stone panel of the god Revanta from auction house Christie’s US branch.

“Their return signifies a cultural revival and a powerful message—heritage belongs to its roots,” said Nandini Sahu, spokesperson and joint director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). “They are fragments of India’s soul.”

However, of the 640 antiquities, only about a dozen—including the Parrot Lady statue, now in the Khajuraho Museum—have been returned to the temples or locations they were taken from.

“Most of these are in Tamil Nadu,” said an ASI official speaking on condition of anonymity.

After they land in India, the rest usually end up in one of two places: the ASI’s Gallery of Confiscated and Retrieved Antiquities and its Central Antiquities Collection (CAC) in Purana Qila or the National Museum. Not all are on public display.

“The ASI should not keep them in closed rooms and should display them at site museums. ASI is only a custodian. It’s public property,” said DN Dimri, former director of antiquities at the ASI. “Things are being brought back with so much effort, then effort should also be made to send them back to their place of origin.”

Not all the idols returned to Delhi get the gallery spotlight. Many are kept out of public view, tucked away in the ASI’s highly secured Central Antiquity Collection in Purana Qila.

Also Read: Villagers use Saraswati riverbed for cow dung, cremation, crop. ‘Where do we keep cattle?’

Art galleries to altars

It wasn’t just another busy day at Chennai Central station. Priests in traditional attire waited, musicians stood poised with drums, and curious onlookers strained their necks as the Tamil Nadu Express from Delhi pulled up to the platform. It was carrying a precious cargo: a 16th-century Nataraja statue that had been stolen in 1982 from a temple in Tamil Nadu’s Tirunelveli district.

As the idol emerged from the railway coach, the notes of the Siva Bhoothagana Vadhyam, a composition dedicated to Lord Shiva, filled the air. Priests broke into hymns, their voices rising in praise. That day, 13 September 2019, marked the idol’s long-awaited return to the state after it was traced to the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) and repatriated.

“We were excited and fortunate to have our Lord back,” said M Krishnamurthi, head priest of the Kulasekaramudaiyan Samedha Aramvalartha Nayagiamman temple in Kallidaikurichi, Tirunelveli.

The priest recounted the moment the idol was taken out of its sealed box at the station. He draped the idol made of panchaloha (an alloy of five metals) with a silk veshti, decorated it with flowers, and performed a pooja.

“After the legal process, the deity arrived in our temple. From then, it has been worshipped with full rituals,” he said.

For decades, the temple had been using a replica of the Nataraja idol.

“We finally replaced that one with the original idol. It’s like the homecoming of our deity,” he added.

It will be of no use if the antiquities remain locked in store rooms. There is a need to speed up the process of transferring after coming back to India

-DN Dimri, former ASI director of antiquities

And that’s where the idol has stayed except for a short detour that year when it was produced in the court of the additional chief judicial magistrate court at Kumbakonam to establish its provenance.

The Nataraja is one of several stolen artefacts returned to their original sanctums by the idol wing CID (IW-CID) of the Tamil Nadu Police, which also investigates idol thefts.

In 2022, the unit facilitated the return of three more idols: a Nataraja bronze statue to the Kailasanathar temple, a bronze idol of child-saint Sambandar to the Sayavaneswarar temple, and a Shiva-Parvati idol to the Vanmeeganathar temple.

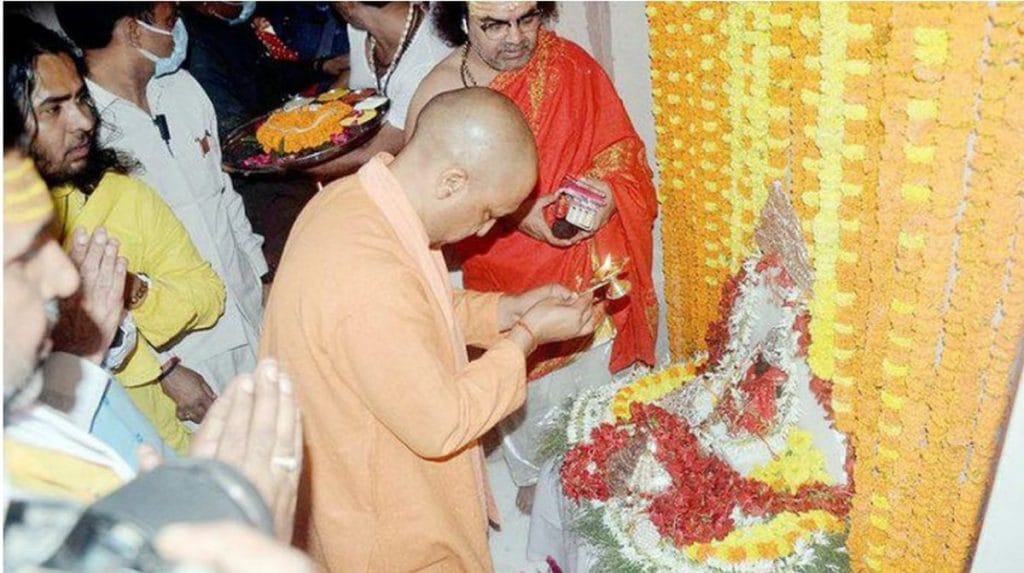

Most of the stolen idols returned to temples are from Tamil Nadu, but in 2021, an 18th-century idol of Maa Annapurna was installed at the newly constructed Annapurna temple inside the Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor in Varanasi.

The statue, smuggled out of India in 1913 by Canadian lawyer and arts patron Norman MacKenzie, was handed over to the ASI in 2015. Worshipped as the goddess of food and a manifestation of Parvati, Maa Annapurna is also called the Queen of Varanasi. The idol’s four-day journey from Delhi to Varanasi ended in a grand ceremony led by Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath.

“After 108 years, Maa Annapurna’s idol has returned to Kashi once again. The credit goes to the MP from Kashi PM Narendra Modi,” said Adityanath at the event.

Despite the official count of 640 artefacts retrieved in the past decade, however, nearly half—297—have yet to arrive in India. These were handed over by the United States during Modi’s September visit and received the sanction order for transportation to India on 16 December.

Of those that are in the country, the majority are still in Delhi, said the ASI official quoted earlier.

Found and ‘lost’ again?

Not all the idols returned to Delhi get the gallery spotlight. Many are kept out of public view, tucked away in the ASI’s highly secured Central Antiquity Collection (CAC) in Purana Qila.

These antiquities rarely receive special treatment. The ASI follows its standard protocols for conservation, but public display remains limited and selective.

“When an antiquity is received by ASI, curatorial and conservation experts examine its state of conservation,” said Sanjib Kumar Singh, museologist and former spokesperson of the National Museum. “The top officials of the ASI decide what to display for the public or not.”

But even artefacts displayed in public don’t always seem to receive regular upkeep.

In 2017, the Seated Buddha statue was repatriated with great fanfare and welcomed at the National Museum by then Culture Minister Mahesh Sharma. This sandstone statue, over 2,000 years old and stolen from Mathura in 1992, was returned from Australia. It now sits outside the office of the museum’s director general. While age has left it with broken parts, more recent neglect is evident—on an afternoon this month, there were cobwebs on its right hand.

Critics argue that government institutions are not always ideal custodians for such treasures.

In a 2016 article, author and economist Sanjeev Sanyal wrote that artefacts, especially temple idols, belong with their original communities.

“The famous Pathur Nataraja, for instance, was retrieved from Britain in 1991 but has not been seen since,” he pointed out. Temple idols, he added, are part of living traditions, and their “real beauty and meaning” only emerge in these contexts.

Objects are coming to our country, but are we doing their qualitative assessment or turning them into non-performing assets?

-Noted art historian

Similarly, academic and conservationist Samayita Banerjee has raised concerns about systemic neglect. In a 2018 article, she cited the theft of 1,300 miniature paintings from Jaipur’s City Palace Museum and the disappearance of 125 antique jewellery pieces from the National Museum in 1968. Banerjee warned that artefacts returning home risk being ‘lost’ again—both literally and figuratively.

Returning artefacts to their original homes, though, is no simple task.

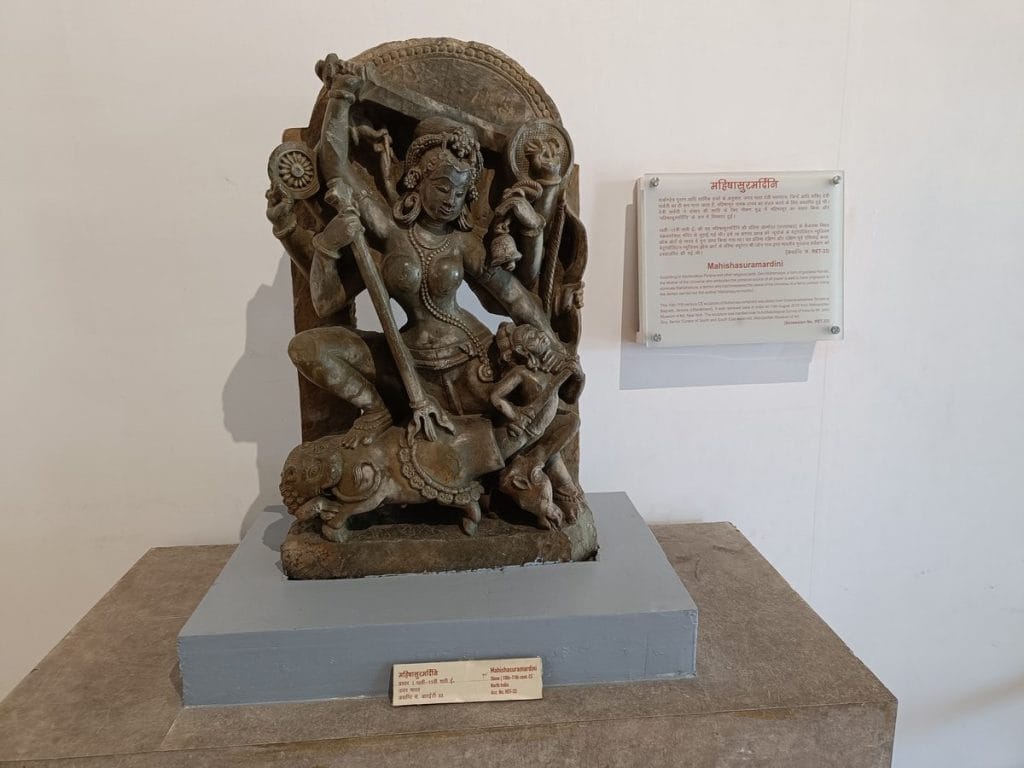

During his tenure as director of antiquities at the ASI from 2014 to 2019, DN Dimri said he oversaw the return of several artefacts to their regions of origin, including a Mahishasuramardini statue, stolen from Pulwama and repatriated to a museum in Srinagar.

“It will be of no use if the antiquities remain locked in store rooms. There is a need to speed up the process of transferring after coming back to India,” Dimri said.

However, many artefacts remain in storage due to lack of documentation, as well as logistical and security concerns.

Dimri pointed to the case of a carved stone Nataraja stolen from Rajasthan’s Baroli temple complex in 1998. Even after its repatriation from the UK in 2020, it could not be returned to its original site.

“There are no proper security arrangements in that area, so the statue could not be sent to the original place,” Dimri said. “Care also has to be taken that the statue does not get stolen again.”

Last year, a Parliamentary Standing Committee report on heritage theft said that out of an estimated 58 lakh antiquities in India, only 16.8 lakh have been documented so far.

Stolen heritage on show

In a hushed corner of Delhi’s Purana Qila, Rohit Gupta’s eyes widened as he stood before a gently spotlit 12th-century Chola-period Sridevi statue. The deity stood in a graceful tribhanga posture, holding a lotus stem in her raised left hand. For the Delhi University history student, the Gallery of Retrieved Antiquities was a vivid connection to his coursework. And it stoked his national pride.

“Recently, I have gone through the Chola Kingdom in my textbooks. So, I was in a quest to find some of the statues and see them, and my search brought me to Purana Qila,” said Gupta, who was there on a weekday along with about five other visitors. “This gallery stands as a poignant reminder of a nation’s unwavering quest to reclaim its stolen past.”

In this corner of the Mughal fortress, visitors step into a different timeline altogether. The U-shaped gallery, an extension of the CAC, was inaugurated in 2019 with nearly 200 artefacts recovered from across the globe, although many also ‘travel’ to other museums or exhibitions. Most of these treasures, spanning the 2nd century BC to the 19th century AD, also have dramatic 21st-century return stories.

For instance, the Sridevi statue that Gupta admired, originally from Tamil Nadu, was seized by Homeland Security in New York and returned to India in 2016 aboard PM Modi’s Air India One.

Gallery staff claim more than 100 visitors arrive daily to view the retrieved artefacts.

“Kitni behtareen kalakari hai. Hazaron saalon ke baad bhi chamak barkarar hai (What amazing craftsmanship. Even after thousands of years, the shine is intact),” said an elderly visitor to a companion, admiring a 12th-century bronze sculpture of the goddess Parvati.

But it’s ‘whereabouts unknown’ for much of India’s artistic heritage.

Last year, a Parliamentary Standing Committee report on heritage theft said that out of an estimated 58 lakh antiquities in India, only 16.8 lakh have been documented so far.

And though loot of temple idols by invaders and colonial rulers have long captured the public imagination, much of the pillaging has occurred in more recent decades. UNESCO estimates that around 50,000 pieces of art were stolen from Indian temples between 1979 and 1989, many now housed in Western museums or private collections.

As archaeologist Vinay Kumar Gupta noted in a 2019 paper, “lawful and organised looting by the colonial powers changed into unlawful and disorganised looting.”

Chasing a lost past

The government’s drive to bring back antiquities only targets items stolen after Independence. India’s British rulers used various legal mechanisms to legitimise their loot, and much of it is now protected by laws like the British Museum Act of 1963, which blocks their return.

But even with more recent thefts, getting antiquities back can be a wild goose chase. In many cases, it has taken several years.

Two first-century Mithuna sculptures, stolen in 2009 from the ruins of a Vishnu temple in Kota, had a convoluted trip back.

One of the stolen pieces was spotted in an advertisement in a 2010 issue of Art of Asia, a Hong Kong journal. The lead came from French national Michel Postel, who tipped off then Indian ambassador Rajan Mathai. Interpol issued an alert, and the US Department of Homeland Security eventually seized the sculptures, which were returned to India in 2017. The sculptures are now displayed at the Purana Qila gallery, with a red placard telling their story.

“Most of the antiquities were acquired by art dealer Subhash Kapoor,” said DN Dimri, former director of antiquities at the ASI. Kapoor, one of the world’s most prolific art smugglers, is currently in jail in India.

The bulk of the 640 antiquities retrieved in the past 10 years have come from the US, numbering 578, followed by Australia, Singapore, Canada, Germany, and the UK. In July 2024, India and the USA signed a cultural property agreement on the sidelines of the 46th World Heritage Committee to curb illicit trafficking of Indian artefacts.

“Before and after independence, statues were taken out of our country in an unethical manner. With India’s growing reputation around the world, various countries have started returning its heritage to India,” said PM Narendra Modi in May 2023, adding that no museum in the world should hold on to any artwork acquired unethically.

Filling the gaps—or not?

The returning antiquities boost national pride and are seen as a sign of India’s global might. But it is uncertain if they are filling a critical gap in scholarship. Art historians are yet to engage with them for research. They have raised questions about the uniqueness of the returned objects.

“In the West, museums are dynamic, and university students often write research papers on antiquities. Objects are coming to our country, but are we doing their qualitative assessment or turning them into non-performing assets?” asked a renowned art historian, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The movement of these antiquities has to go through through proper documentation and checks. And before transportation, conservation status has to be checked. It is not possible to display all the antiquities

-Nandini Sahu, spokesperson and joint director general, ASI

He also questioned whether retrieved antiquities sent to museums are accompanied by adequate budgetary support for their upkeep and study.

Even as India pours resources into diplomatic, logistical, and legal efforts to bring back antiquities, the historian pointed out that India often already has similar specimens. So, they don’t necessarily add to existing historiography.

“Objects coming from abroad do not mean that they are of excellent quality. Objects of better quality are already kept in the National Museum,” he said, referring to their uniqueness and scholarly significance.

Also Read: Could Vadnagar rewrite history? 3,000-yr-old Gujarat town holds clues to India’s ‘dark age’

Paper trail and roadblocks

Retrieving stolen antiquities is only half the battle. Pinning down their origins and verifying documentation can be just arduous. The ASI’s antiquity wing must investigate each artefact’s provenance. Only when it matches beyond doubt with historical records is it sent back to the place from where it was stolen.

“For this, the theft report or any missing report with the ASI is checked,” said Nandini Sahu, spokesperson and joint director general, ASI. But sometimes, even police complaint records are missing—or have themselves been stolen.

Earlier this month, the Supreme Court said it was “shocking” that fresh FIRs were filed in idol theft cases after 41 police files went missing in Tamil Nadu. The petitioner alleged a “serious conspiracy” involving police, civil servants, and organised crime, with the stolen idols valued at Rs 300 crore on the international market.

A lack of documentation can delay a final homecoming for years or even decades. A 12th-century bronze Buddha repatriated from the UK in 2018 remains in the custody of the ASI. Of 14 bronze statues stolen from Nalanda Museum in 1961, only one has been recovered; it’s been stored at the CAC since its repatriation in 2018.

Despite such incidents, progress has been made, according to Sahu, who gave the example of the Kaliya Marthana Krishna, a Chola-era bronze statue that was handed over to the Tamil Nadu idol Wing in September.

“The movement of these antiquities has to go through through proper documentation and checks. And before transportation, conservation status has to be checked,” said Sahu. “It is not possible to display all the antiquities. So, we have to keep it somewhere. That is the Centre Antiquities Collection.”

The ASI’s conservation wing oversees these status checks for fragility and other parameters.

“Only a few objects were shown during the G20. Movements of sensitive antiquities are not done. These artefacts are our heritage and important for understanding the past,” said Arvin Manjul, archaeologist and director (antiquities) at the ASI.

But for some, these antiquities are as relevant today as they were centuries ago.

An emotional homecoming

In 2022, Tamil Nadu’s Idol Wing CID handed over a bronze idol of a standing Sambandar to the Sayavaneswarar temple in Tamil Nadu’s Sayanavam village—over 50 years after it was stolen.

The statue of Sambandar—a revered Shaiva poet-saint of the 7th century, who composed over 16,000 hymns dedicated to Lord Shiva—was “voluntarily returned” by the National Gallery of Australia.

“Finding the idol and reinstalling it in the temple was no less than a dream come true,” said B Chandrasekara Sivachariyar, an 80-year-old priest at the Chola-era temple.

The priest recalled that the idol was stolen when he was around 20 years old. Its return saw village-wide celebrations, with the entire temple decorated and special prayers performed.

“It was an overwhelming moment. Everyone’s eyes were moist when the idol was returned,” he said.

For him, the Sambandar idol’s return elevated the temple’s prestige. Along with the Shiva idol, it is now worshipped every day.

“Sambandar’s hymns are now included in the daily prayers,” he added.

“I didn’t think I would live to see this again in my lifetime,” he said.

“Sambandar’s hymns are now part of the worship rituals,” said the priest. “I didn’t think I would be able to see this again in my lifetime.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

What and all we human beings do on imagery or idolatry is having the origin in our Mind which is everlasting eternal energy. Whole world is encoded in Mind. Pursuing is timeless whether it is about past – great or dead and future whether it will be for reaching – higher or beyond. The point is keeping the Enlightened awareness meditating mind.