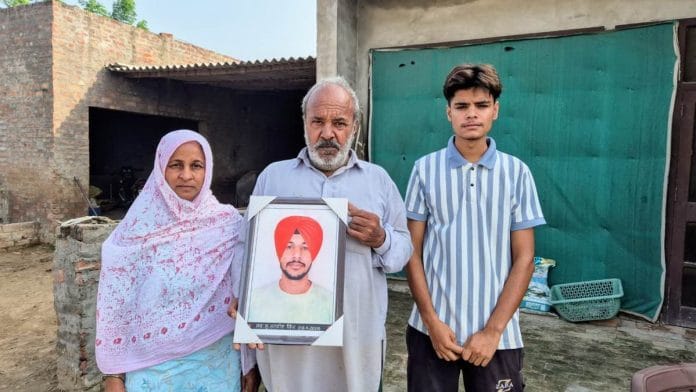

Mansa: The father stares into the distance, fighting back tears as the memory of his 25-year-old son Tanveer grips him. He says the image of his boy lying lifeless in the field, pesticide frothing at his mouth, replays in his mind every night. What haunts him more than that image is the Rs 5 lakh debt that drove his son to take his life.

The Green Revolution state of Punjab is ironically in the middle of an acute farm debt burden. The farmers holding the grain bowl of the country are drowning under loans today—a spectre that has come on top of the state suffering from alarmingly low groundwater tables, unsustainable MSP-dependent crops, lack of industries, and unemployment.

“At this age, I am back in the field. Bank agents visit my house almost every week. I have to look after my younger son’s welfare,” said Tanveer’s father Dilraj Singh, a marginal farmer and resident of Bhaini Bagha village of Mansa in the Malwa region.

Farmer union leaders say nearly every fourth household in Bhaini Bagha has lost a young man who found death easier than relentless pressure from loan sharks. While NCRB data shows farm suicides in Punjab declined from 302 in 2019 to 174 in 2023, unions say cases are severely underreported, with many deaths attributed to other causes. These men have left behind families now burdened by both grief and debt — young widows and ageing parents trapped in the same cycle their sons could no longer endure.

Punjab’s agricultural crisis is a vicious cycle. The wheat-paddy system keeps farmers barely afloat, even as it depletes soil health, groundwater, and long-term prospects. Input costs climb while earnings stay flat. Crop diversification is promoted as the fix, but without support or secure markets, farmers cling to the ‘safety’ of rice and wheat, deepening the crisis. There are not enough industries and jobs and the state’s once-strong entrepreneurial energy is sputtering. The result is slow implosion.

The question of how to implement diversification has never been addressed by policymakers or the government, they’re only giving sermons to the farmer without policy input or mix

– Devinder Sharma, agriculture expert

Drug abuse and dunki migration are two of the most visible fallouts. Another is debt, the burden of which is proving fatal for many. The average monthly income of farmers in Punjab is the second highest in India at about Rs 26,000 a month. Yet the average debt per agricultural household in Punjab stands at Rs 2.03 lakh, the third highest in the country after Kerala and Andhra Pradesh. Over 54 per cent of the state’s farming families are in debt. Total farmer loans exceed Rs 1.4 lakh crore.

“I earn close to nothing,” said Dilraj Singh, who cultivates wheat and capsicum. “I owe the aarthiya (middleman) money, so he deducts the loan amount from the produce that I take to the mandi. I get almost nothing for myself, except kanak (wheat). Can I run my house with that amount?”

The state itself is buckling under debt. In 2025, NITI Aayog ranked Punjab last among 18 major states on fiscal health. The government’s debt is about Rs 4.17 lakh crore, with about 40 per cent of its revenue spent in servicing it and paying interest. Punjab’s youth unemployment rate is 20.2 per cent, well above the national average of 14.6 per cent, according to the Periodic Labour Force Survey’s April-June 2025 data.

More than half the rural population depends on farming according to the Punjab State Warehousing Corporation, but the state does not have a formal agricultural policy. Little has been done to move farmers beyond paddy, which threatens to hollow out the state from the ground up. The last farm loan waiver came in 2016. Redressal systems barely function. This year, the worst floods in decades and Trump’s tariffs have only added to the pressures for farmers.

“Punjab is caught in a chakravyuh with no way out,” said economist RS Ghuman, Professor Emeritus at Guru Nanak Dev University. “The state of Punjab is not in a position to solve its debt crisis, and the central government is not in a mood to do it.”

He added that 80 to 90 per cent of all suicides are in the Malwa region, where after cotton failure about a decade ago farmers shifted to paddy.

The paddy trap

At the centre of Punjab’s agrarian climate crisis is the over-reliance on paddy. A crop that once made the state rich is now bleeding it dry and only band-aid fixes are on offer.

While only about 30 per cent of the state’s land is suited to the water-guzzling crop, it’s now grown on 64 per cent. It needs roughly 5,000 litres of water to produce a kilo of rice, yet free power for irrigation and fertiliser subsidies make it the easiest choice. The Minimum Support Price (MSP) and government procurement guarantee a buyer for every sack of grain.

About 90 per cent of Punjab’s Kharif acreage (32.4 lakh hectares) is under paddy and 97 per cent of Rabi land (36 lakh hectares) is under wheat.

But a system meant to protect farmers from exploitation now risks desertification of the food bowl of India. Crop diversification is advocated but few meaningful incentives exist to promote it. Maize, pulses, oilseeds, or vegetables are seen as risky as they fluctuate in price and don’t have procurement support.

“Other crops simply don’t give the farmers the kind of assurance and yield that paddy does, so they’re unwilling to move from it,” a member of the farmer welfare board said on the condition of anonymity.

But it’s also about a deeper stagnation of Punjab’s entrepreneurial spirit. There’s a strong resistance to change, as evident in the 2020-21 protests against the three farm laws that sought to reduce the role of state-run Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandis.

No farmer can only rely on agriculture as their source of income. They won’t be able to earn money if that is the case. They need to diversify and do something else

-Gora Singh, farmer and Bharatiya Kisan Union (Ugrahan) leader

“No state needed agricultural reform more than Punjab, given the talent and entrepreneurship of its farmers that created the Green Revolution. Yet, none was more opposed to it. It came from broken politics, decades of frustration and the single-focus evolution of its entrepreneurial virility: emigrate, emigrate, emigrate,” wrote ThePrint Editor-in-Chief Shekhar Gupta in a 2023 column.

According to data from Punjab Agricultural University, returns over variable costs for wheat, barley, and maize average about Rs 43,000 per acre. For gram and lentil, returns hover at Rs 25,084, and for summer moong and mash, it’s Rs 30,997 per acre. These estimates don’t include labour cost. Lentils yield only 4.5 quintals per acre and have no guaranteed market. Paddy, by contrast, gives an estimated yield of 30 quintals and fetches Rs 41,148 per acre.

Agriculture expert Devinder Sharma, part of the Supreme Court’s high-powered committee on agrarian reforms, hinted at Punjab’s agrarian success becoming its own obstacle.

“The productivity of Punjab is among the highest globally if you take wheat and paddy—about 11 tonnes per hectare per year, among the top five in the world,” he said. “There’s also almost 100 per cent procurement of wheat and paddy from farmers because they desire an assured price. If we start offering the same for diversified crops, then they would also shift.”

Sharma noted there’s awareness among farmers that wheat and paddy have done enough damage to soil and water, but other crops were never given a fighting chance at the policy level.

“The question of how to implement diversification has never been addressed by policymakers or the government, they’re only giving sermons to the farmer without policy input or mix,” he added.

When diversification fails

The few villages that turned to diversification haven’t gained much either. In some, the profits look good on paper, but there’s deep anxiety beneath the veneer of prosperity. And the pull of paddy never really goes away.

In Bhaini Bagha, about 500-600 of the village’s 4,000 acres are under capsicum, which can yield profits of Rs 2-3 lakh per acre. But in summer, farmers switch back to paddy, earning around Rs 1 lakh per acre.

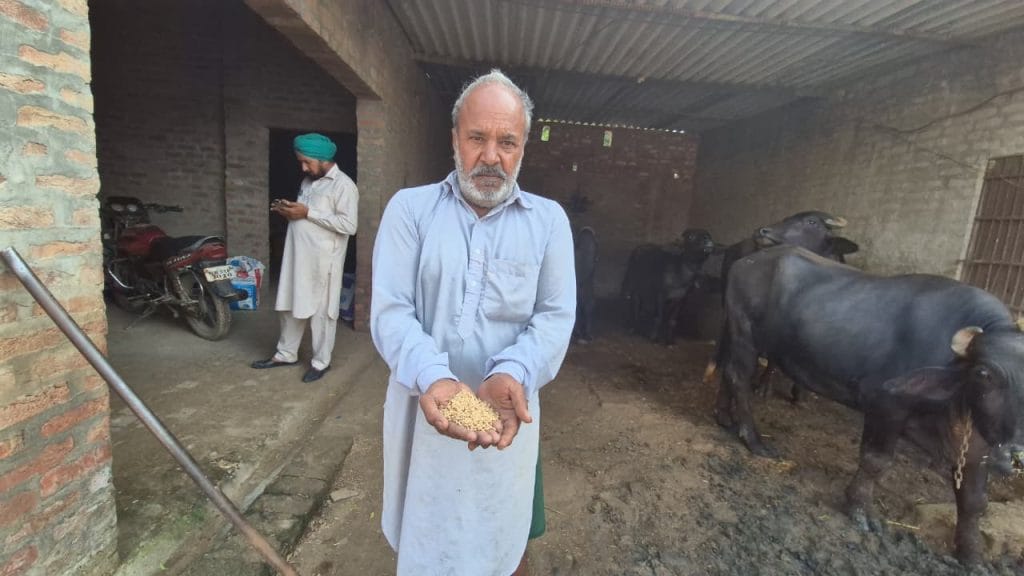

Among them is BKU (Ugrahan) leader Gora Singh, who has been growing capsicum and wheat for over a decade. Despite his earnings, his income is stretched.

“I myself am in debt of Rs 10 lakh. There is so much expenditure to do in agriculture. From fertiliser, to tractor. And we also have other expenditures as well, like healthcare and weddings,” Singh said.

No other crop is being procured at MSP even if that is announced by the government. And if there is farmer-level initiative, it fails. Also, even if a small area is diversified, farmers face a market glut in the mandis

-Professor RS Ghuman

On the policy front, the results of recent attempts at diversification are yet to be seen.

In the 2025-26 state budget, Rs 115 crore was earmarked for diversification, including pulses and maize. A few months later, the Punjab government launched pilot projects for maize in Sangrur, Bathinda, Pathankot, Gurdaspur, Jalandhar, and Kapurthala, offering Rs 17,500 per hectare incentives and procurement at Rs 2,400 per quintal.

However, earlier initiatives such as the 2024-25 PHASE (Punjab Horticulture Advancement and Sustainable Entrepreneurship) scheme for crop diversification and the Bhav Antar Bhugtan Yojana, a price-risk mitigation programme introduced the year before, reportedly never took off and weren’t even mentioned in this year’s budget.

“Crop diversification is a nice buzz word and we have been talking about it for a long time, but on a policy level nothing has been done to really incentivise the farmer to move away from paddy,” Sidhu said.

Professor RS Ghuman also said that no viable substitute for paddy exists, much as was the case 20 years ago.

“No other crop is being procured at MSP even if that is announced by the government. And if there is farmer-level initiative, it fails. Also, even if a small area is diversified, farmers face a market glut in the mandis,” he said.

The answer to the agrarian crisis, Ghuman added, is simple: setting up industries and creating jobs.

Gora Singh echoed this, noting that what’s necessary is not crop diversification but business diversification.

“No farmer can only rely on agriculture as their source of income. They won’t be able to earn money if that is the case. They need to diversify and do something else,” he said.

Debt spiral

Despite the rich farmer stereotype, many in Punjab are using loans to prop up their farms and households. It’s a land of extravagance and emigration dreams, but realities haven’t kept up. Many now live in fear of aarthiyas — the commission agents who lend them money and recover it at harvest.

Much of what farmers borrow today goes into hospitals, weddings, and school fees. In Malwa, healthcare especially pushes families into crippling debt. The cotton belt is now called the cancer belt due to the high number of cases, linked to the use of chemical pesticides and fertilisers.

Keeping up appearances adds to the burden. One farmer, who was participating in a protest demanding compensation for flood damage to crops in Mansa district, told ThePrint how his sons forced him to take a debt of Rs 4 lakh to buy a car, promising to repay it.

In proportionate terms, Punjab has been very susceptible to farmer suicide. For farmers without supplementary income, it becomes very difficult to afford basic things like children’s education

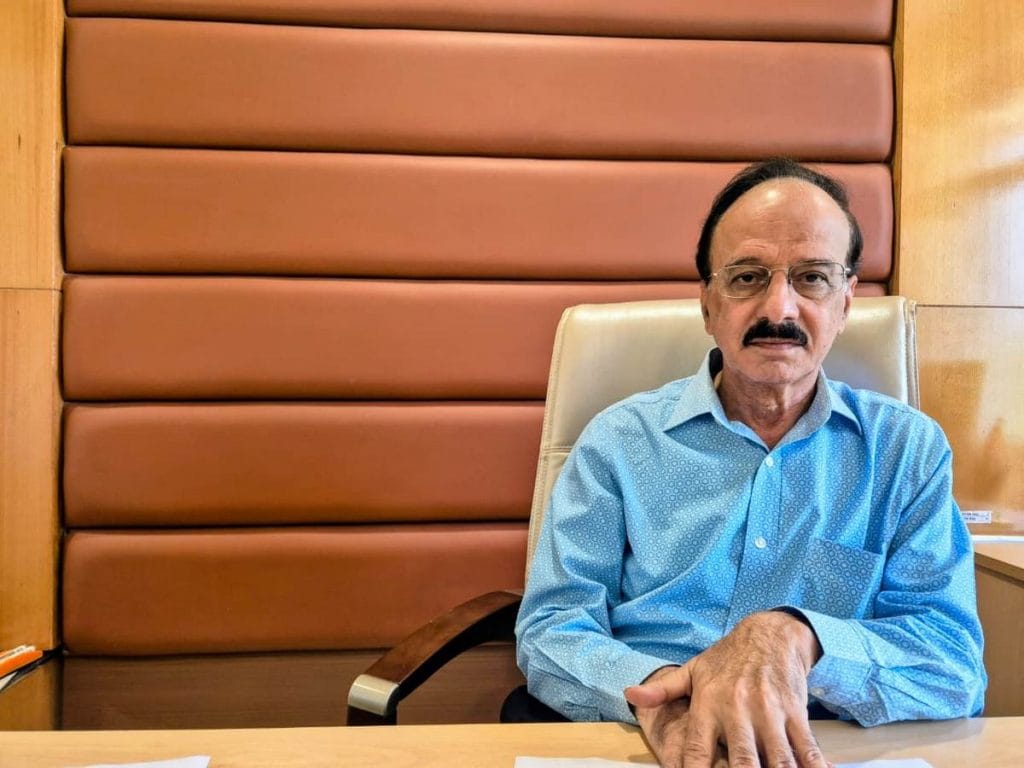

KBS Sidhu, former special chief secretary, Punjab

“My sons are now unable to pay the loan, and the bank has claimed a stake on my entire land of 2 acres. I am completely stuck,” the farmer said, asking not to be named.

But Ghuman cautions against pinning the blame on farmers’ choices.

“A lot of people blame Punjabi extravagance over the high debt — while that may be an issue, it is not the issue,” he said. Instead, he pointed to spiking costs and diminishing returns.

“When return on paddy increases, then rent of land also increases exorbitantly. It can reach Rs 80,000-90,000 per acre, one of the major reasons for high farmer indebtedness. Tenancy in Punjab is very high where 25 per cent of all land is leased out,” he said.

At the same time, growth rate of net income per acre is declining and cost is constantly increasing.

“Incremental cost is higher than incremental yield,” said Ghuman, adding that crop failure and over-mechanisation of farms are common culprits as well.

Even small and regional farmers buy heavy-duty equipment like super seeders and tractors, which have high maintenance costs. Many say they go in for purchases because community equipment is inaccessible.

“The tractors available at the panchayat or with big landowners are given on a lottery system. They’re not easily available, and the rent is also very high,” said Gora Singh.

Invisible suicides

With a toddler in her arms, 31-year-old Manjeet Kaur looks with resigned anger at a portrait of her late husband.

“I have made peace with the fact that the journey ahead is going to be a difficult one,” she said. A year ago, her husband Harpreet, a farmer, consumed pesticide at home. He was rushed to hospital but died nine days later. In the agony of those last days, he had clarity.

“He said, ‘I am sorry, I didn’t think of you or our son before taking this final step. What will happen to you if I die?’” Manjeet recalled.

Harpreet owed Rs 8 lakh, and Manjeet accrued an additional debt of Rs 2 lakh while he was hospitalised.

“Harpreet used to be upset all the time. Our house is falling apart, there’s seepage in every wall. He had many people to pay off and consumed alcohol under stress,” she said.

Former Punjab special chief secretary KBS Sidhu said that most farmer households are small or medium, holding about 2 acres, though on paper they appear bigger since they take land on rent.

“In proportionate terms, Punjab has been very susceptible to farmer suicide. For farmers without supplementary income, it becomes very difficult to afford basic things like children’s education,” he added. “Even though there has been a notional dip in numbers in the past two or three years, the problem of suicides isn’t something the state should ignore.”

My son spent his life trying to rid us of his father’s debt, who had died after a year of crop failure. And now he’s dead too

-Rani Kaur, who lost both her husband and son Harpreet to suicide

Many of these deaths go uncounted in official statistics, which have consistently shown deaths in the low hundreds each year. However, a 2016 survey by Punjab Agricultural University, Punjabi University, and Guru Nanak Dev University recorded 16,000 farmer suicides between 2000 and 2015.

Bhaini Bagha village lies in Punjab’s Malwa region, where indebtedness and farmer suicides are most common. The belt was worst affected by a whitefly infestation of cotton crops in 2015. Many farmers were compelled to take loans and shift to paddy cultivation.

Even though landholdings here are relatively bigger than in other parts of the state, farm suicides are mostly reported from this region— known as Punjab’s political heart.

Harpreet’s case is one of generational debt. Thirty years ago, before he was born, his father had died by suicide in the exact same way.

“My son spent his life trying to rid us of his father’s debt, who had died after a year of crop failure. And now he’s dead too,” cried Rani Kaur, Harpreet’s mother.

Both Harpreet and Tanveer’s families haven’t received the Rs 3 lakh compensation given by the government in suicide cases, which are often hard to prove.

In Harpreet’s case, the FIR didn’t use the word “suicide”, so his death was treated as an accident, Manjeet said.

“The omission of just one word has cost me so dearly,” she wept.

Also Read: Dalit women reclaiming Punjab’s farmlands. ‘We are born on this land, have a right to it’

Conflicts of interest, policy failure

Hounded by loan recovery agents, friends Tanveer and Harpreet died within a month of each other in Bhaini Bagha. Even now, bank representatives knock on their families’ doors demanding payment.

A huge chunk of their debt wasn’t from banks but informal moneylenders. Their families say that even after years of repayment, the interest keeps mounting and the goalpost keeps drifting away.

Informal lenders, typically big farmers or middlemen, tend to charge exorbitant interest rates, ranging between 18 and 24 per cent, trapping small cultivators in endless debt cycles.

The last farm loan waiver came in 2016, under then Chief Minister Captain Amarinder Singh — the first since 1987. According to the state’s farmer welfare board, loans worth Rs 4,160 crore were waived, but 1.15 lakh applications are still pending.

The tribunals have failed completely. There’s no mechanism to file complaints, no separate office, no website. Farmers are not aware, and there’s no participation

-Col (retd) Jasjit ‘Jass’ Gill, social activist

The problem is compounded by a conflict of interest, according to Sidhu— many commission agents are also union leaders. This means the problem of farmer indebtedness is often ignored at the union level.

“These are the people who are incidentally farmer leaders, the very people who should be addressing the problem of high-cost debt. The dual role of aarthiyas and conflict of interest must be studied. They keep blank cheques signed from farmers to deduct payment whenever it comes in,” he said.

A mechanism to protect farmers from such exploitation exists largely in theory— the Punjab Settlement of Agricultural Indebtedness Act 2016, which was passed as a response to the farmers’ protests after the whitefly attack on cotton.

It was intended to create district-level forums and a state tribunal to settle disputes over non-institutional debt quickly. It superseded the Punjab Relief of Indebtedness Act, 1934, which aimed to regulate harsh debt recovery practices and allow resolution through conciliation instead of lengthy litigation. Neither law did much to redress farmers’ concerns.

An amendment in 2018 reduced the proposed 22 district-level forums to just five division-level ones, and even these never took off. It has been speculated that the amendment was necessitated by retired judges refusing to work in these forums because of the paltry salary.

As a 2018 article in the Tribune put it: “Had the Punjab Government even allotted a fraction of the loan waiver budget to set up a dedicated and funded debt relief forum, the agricultural debt landscape could have at least started changing a bit.”

This state of affairs has been unfavourably contrasted with the Kerala State Debt Relief Commission, which was started in 2007 with an initial budget of Rs 130 crore and heard 2,000 cases a month. While this model too has been criticised in recent years for being “toothless” and “paralysed” by lack of funds, it’s still functional with a website that provides occasional updates.

In Punjab, though, many farmers and union leaders said they had never even heard of the state’s tribunals. ThePrint contacted Revenue Secretary Manvesh Sidhu via e-mail and WhatsApp. This report will be updated if a response is received.

Colonel (retd) Jasjit ‘Jass’ Gill, an Army veteran and social worker, has filed a writ petition in the Punjab and Haryana High Court seeking a moratorium on all agricultural loans until these tribunals become operational.

“The tribunals have failed completely. There’s no mechanism to file complaints, no separate office, no website. Farmers are not aware, and there’s no participation,” Gill said over a Zoom call. He filed the petition in 2016 and it is still pending, which he claimed “means the government has not satisfied the Punjab and Haryana High Court.” The next hearing is in November.

Gill also said that the issue of high interest rates charged by NRIs or arthiyas or zamindars should also be addressed. He pointed out that the government failed to act on a 1930 law called the Punjab Regulation of Accounts Act, mandating middlemen to keep detailed records of loans extended to farmers.

“If businessmen can have tribunals like NCLT [National Company Law Tribunal], why not a farmer who can go to a tribunal with their grievances?” Gill said. “These are small Rs 2-3 lakh loans over which farmers are dying by suicide.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

A good article by the Print. The Central Government must take concrete steps to help guide farming in Punjab towards less ecologically harmful practices. Correct application of financial incentives, such as the ones highlighted in this article, can play a role in this. Any money spent supporting these hardworking families will pay back many fold in terms of a better and more diversified food supply for the country.

I don’t think we can blame central government for farmers’ low income at this time because farmers reforms in bring were vehemently opposed by the farmer unions. Given the widening gap between price consumers pay and price farmers get for crops, marketing reforms are need of hour that was pushed back

The solution to Punjab (and Other States) is to “embrace” AgriVoltaics (AV) that enables one to Graze and Grow food below as one generates Pollution Free Solar Electricity above.

Using 5% of India’s 2.2 Million km2 of Farmland, AV can provide ALL the Energy Needed for a ZERO POLLUTION BHARAT… Bharat 2050 …. with a 15TW, 18,000TWh/yr AV System.

This System, financed by State/Central Govt’s Implementing the 1992 UN Rio Agreement, PRINCIPLE #16 (already accepted by the GOI), can provide USD2+Trillion/yr, PAID BY THE POLLUTERS IN INDIA ONLY. It can FINANCE the above, as it Transitions the Dirty-n-Polluted India today, to a ZERO POLLUTION BHARAT by 2050… or earlier. This also halts the 2.5 Million Premature Deaths annually and 35Million DALY of Suffering caused by Pollution in India… TODAY…

The above PV-AV System, sharing the Farmers Farmland, can generate, from the 18 Trillion KWh/yr of Electricity generated, a Net Income of INR 72 Trillion/yr (INR 72 Lakh Crores/yr), for the Farmers (INR4 / KWhe) in India.

The Punjab farmers will get their own share…. and break-out of this “Chakravuu of Agricultural Debt” ….. forever. ???

NOW….. DO IT…. IMPLEMENT PRINCIPLE #16 & SECURE THE FUTURE OF A ZERO POLLUTION BHARAT & ZERO DEBT FOR THE FARMERS TOO…!!!

Central govt needs to be firm now. MSP of rice must be reduced to discourage rice and promote pulses. Rice procurement from Punjab must be reduced. And procurement from Bihar and Bengal must be increased instead. Give the good quality rice seeds to water-abundant Bihar and Bengal.