Jalna: Diwali was approaching. The school principal’s home in Jalna was abuzz with festival cooking. The OBC cleaner made bhakri flatbread and offered it to the Maratha cook in the house.

What followed was shocking. But it showed how the ongoing Maratha quota protests in Maharashtra are shifting people’s ties on the ground.

“The Maratha lady refused to touch the bhakri made by the OBC woman,” Sunanda Tikde, the principal, recalled.

But the OBC cleaner retorted with a taunt: “Amcha sarkha aarakshan pahije na? Mag amcha haat chi bhakri kha (You want reservation like us? Then, eat the bhakri made by us).”

Tikde’s cook and cleaner are forced to interact with each other at work, but in many villages across Jalna, Marathas and OBCs have turned their backs on each other. Neighbours no longer chat, children have been told to stop playing with each other, and both communities socially boycott each other’s events.

“We had a death in our extended family a few days ago. Normally, the entire village would have turned up to help us, but this time the Marathas stayed away,” said Balasaheb Dakhne, a social worker from the OBC community who lives in Antarwali Sarati village.

People are going about their daily lives, but there’s an undercurrent of tension. Muscle-flexing hoardings by both communities every few metres serve as constant reminders that all is not well.

Tikde, an OBC woman herself, witnessed these fraught caste dynamics playing out in her own house. The altercation reflected the changing equation between the OBCs and Marathas in Marathwada’s Jalna district, the epicentre of protests by both communities.

Traditionally dominant Marathas are now vying for OBC reservations, citing economic hardship. The historically marginalised OBCs are pushing back, determined to protect their government job and education quotas.

The Maratha community has been demanding a quota since the 1980s, but the intensity and trajectory of the movement shifted dramatically this year. Manoj Jarange-Patil, a veteran quota activist from Jalna, has been garnering a swelling following in Maharashtra over the past few months.

His demand: that the BJP-Shiv Sena government recognises Marathas as Kunbis, an OBC caste entitled to reservation benefits, even as the battle for a standalone quota languishes in the Supreme Court.

All Marathas initially belonged to the agrarian Kunbi caste, according to community leaders and historians. Over time, however, Marathas claimed lineage with warrior groups, adopting a Kshatriya identity, while Kunbis retained their Shudra status.

Eventually, the Mandal Commission included Kunbis in the list of Other Backward Classes (OBCs), but left out Marathas.

Now, old wounds related to Maratha dominance have been re-opened. Even OBCs who supported the struggle for Maratha reservation are furious and holding counter-agitations in Jalna.

“They suddenly wanted what was ours,” said Baliram Khatke, an OBC and sarpanch of Vadi Godri village.

Also Read: JCB showering flowers, packed rallies — how Jarange-Patil is building ‘mass leader’ image

The epicentre of protests

A small farmer and a former hotel worker, Jarange-Patil lives in a bare house with one room and a kitchen in a settlement known only as karkhanyacha mage—the place behind the factory—near Antarwali Sarati village. The sugar factory belongs to Rajesh Tope, an MLA of the Sharad Pawar-led Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), but it is Jarange-Patil’s house that is now the most famous landmark here.

Until four months ago, Jarange-Patil was known only in pockets of Marathwada. Then, on 29 August, he organised a rally at Paithan Phata, a junction of villages, and announced that he was launching a full-fledged agitation and hunger strike for Maratha reservation.

“He chose Antarwali Sarati village because of its location. It is central to a number of villages in this cluster and has a spacious courtyard where people can gather,” said Prahlad Baburao Gadgil, a resident of Antarwali Sarati and a Jarange-Patil supporter.

“Our OBC brothers didn’t object and, in fact, helped us.”

Dhangars, Malis, and all others have nothing against us Marathas.

They are being deliberately provoked

—Balasaheb Tarakh, Maratha farmer from Antarwali Sarati village

This was neither Jarange-Patil’s first protest nor his first hunger strike. It could have perhaps ended like all his previous protests—with an assurance from a local government official. However, a police lathi charge altered the protest’s trajectory. While the government faced accusations of police brutality, Jarange-Patil continued with his fast, catapulting himself to hero status.

Overnight, Jarange-Patil went from local activist to a state-wide Maratha leader, and Jalna became the command post in the latest wave of quota protests.

In November, when he launched his next fast, a delegation of state ministers trekked to Jalna to dissuade him. Jarange-Patil relented only after setting a deadline of 24 December, warning that he would “choke Mumbai” if Marathas did not get their OBC caste certificates by then.

However, this outcome now seems unlikely. The OBCs are no longer sympathetic and are holding counter-protests, which included a major rally on 17 November that was attended by leaders across the political spectrum. On the ground, the divide between OBCs and Marathas continues to widen.

There has always been an undercurrent of subtle social discrimination, particularly from affluent and powerful Marathas.

Old resentments, ‘unofficial reservation’

In the cluster of villages surrounding Antarwali Sarati, residents from both Maratha and OBC communities acknowledge a historical sense of kinship. However, there has always been an undercurrent of subtle social discrimination, particularly from affluent and powerful Marathas.

The 1980 Mandal Commission, which paved the way for OBC reservation, classified Marathas as a forward caste. Even amid the reservation fight, there is still a faint trace of this social ‘superiority’ among Marathas.

The Maratha community bands together to get their own elected to power

—Jaidev Dole, political analyst

“There is an unofficial reservation that the Maratha community here benefits from,” said Jaidev Dole, an academic and political analyst based in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (formerly Aurangabad) in the Marathwada region. “Maratha business owners, directors of cooperative sugar factories, and banks hire more people from their own caste.”

However, Santosh Danve, a BJP MLA from Bhokardan in Jalna district, dismissed this claim.

“Look at the list of employees in any such establishment and you will see that there is no disparity,” said Danve, who belongs to the Maratha community. The real problem, he added, was dwindling jobs in sugar factories due to automation and financial strain.

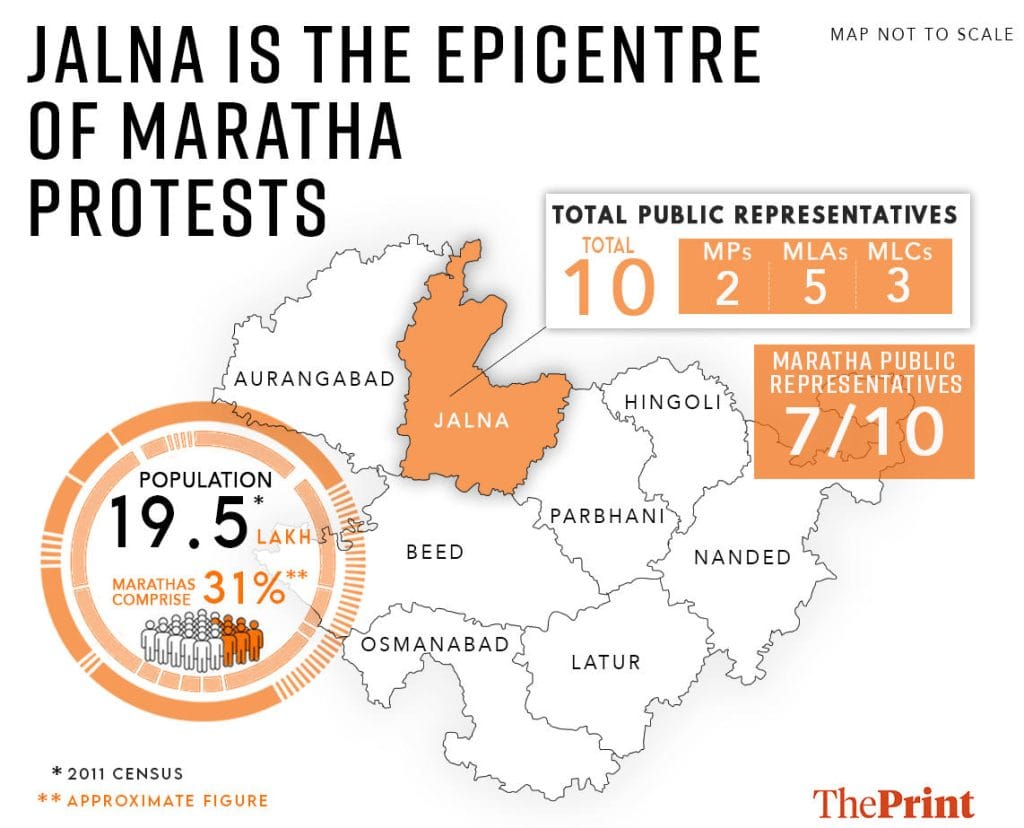

Marathas account for approximately 31 per cent of the state’s population, with the greatest numbers in Marathwada and Western Maharashtra. OBCs constitute over 38 per cent, according to the estimates of the state Backward Classes Commission.

Jalna, situated in the water-scarce Marathwada region’s north and home to approximately 19.5 lakh people, has a similar caste distribution, residents say.

Many OBC leaders occupy important positions in local governance, including village sarpanches and municipal council presidents. However, political representation at the Lok Sabha and state assembly levels has by and large been dominated by Maratha politicians. Of the 10 public representatives from the district—two MPs, five MLAs, and three MLCs—seven are from the Maratha community.

“The Maratha community bands together to get their own elected to power,” Dole claimed.

Satsang Mundhe, a Congress leader who helped organise the 17 November OBC rally in Jalna earlier this month, said there was a longstanding trend of Maratha leaders across parties joining forces to maintain their community’s political dominance in Marathwada.

We never had this sort of a divisive atmosphere between the two communities earlier… there is a lot of bitterness now on the ground.

— Santosh Danve, BJP MLA from Bhokardan in Jalna

“In 2009, when BJP’s Gopinath Munde, one of Maharashtra’s tallest OBC political leaders, was spearheading the preparation for the Lok Sabha election in the Marathwada region, members of the Maratha community were circulating messages saying, ‘Vajli tutari, kara tayari and hatva Vanjari’ (The blowhorn has been sounded, now prepare and displace the Vanjari),” Mundhe said.

Munde, who died in 2014, belonged to the Vanjari OBC community.

MLA Danve told ThePrint that the Maratha community needs reservation due to “a lot of poverty”, but acknowledged that the demand has strained relations with the OBCs.

“We never had this sort of a divisive atmosphere between the two communities earlier. After the lathi charge incident, the Maratha community strongly supported Jarange-Patil as a genuine face (of the movement). Unfortunately, loose talk from some leaders provoked people from both sides,” he said. “There is a lot of bitterness now on the ground. Even if the Marathas get reservation, it looks like this bitterness between the two communities will not go away easily.”

The BJP MLA, son of Union minister Raosaheb Danve, added that even minor incidents are now being given a casteist and political colour. He recounted an incident in which Jarange-Patil accused the Danve family’s supporters of tearing down Maratha community banners proclaiming gaobandi (entry prohibition) for politicians in Antarwali Sarati.

According to Danve, those banners were blocking a local woman’s shop during Diwali celebrations, directly impacting her livelihood. “The woman requested the village sarpanch to have the banners removed for a few days until Diwali was over. It was a local incident that was unnecessarily made to be political and triggered the community further,” said Danve.

ThePrint called and messaged Rajesh Tope, an MLA from the Sharad Pawar-led NCP under whose constituency Antarwali Sarati falls, but no response was received.

When Jarange-Patil organised a mega rally on 14 October near Antarwali Sarati, the OBC residents showed support and solidarity… then a sense of betrayal took over.

Warm welcome to war cry

Marathas, once generally prosperous with large landholdings, saw their wealth and property fragment as families grew. The community encompasses rich landlords and factory owners, but also farmers, and daily wage labourers.

The agrarian Maratha farmers from Marathwada are not much better off than their OBC counterparts.

“The Marathas have always been a dominant political class, but we never had any bitterness with our Maratha neighbours on a day-to-day basis. Economically, they are not very different from us. Everyone here, on an average, has small farm holdings of one to two acres,” said Vadi Godri sarpanch Baliram Khatke. “Manoj Jarange-Patil has also been a friend for many years. He is a simple, well-intentioned man.”

When Jarange-Patil organised a mega rally on 14 October near Antarwali Sarati, the OBC residents showed support and solidarity. They opened their doors to the droves of Maratha visitors and offered them food and water.

“We always supported the Maratha community’s demand for reservation. A few people may be rich and politically powerful, but many Marathas are struggling. Throughout Jarange-Patil’s hunger strike, and especially on the 14 October rally, we helped them in every way we could. Some of us also offered their land free of cost for parking facilities,” Khatke said.

Then, everything changed. A sense of betrayal took over.

“What Jarange Patil said in that rally stunned us,” Khatke recalled.

At that rally, Khatke and other OBC residents heard Jarange-Patil demand loud and clear that the entire Maratha community be given reservation from the OBC quota.

The experience left a bad taste in their mouths. Villagers still complain about how large groups of Marathas trampled all over their crops on their way to Jarange-Patil’s rally.

A month later, on 17 November, the OBC community too held a mega rally in Jalna’s Ambad. OBC leaders from different parties gathered on the stage to protest the Maratha demand for reservation as Kunbis.

They questioned how Marathas could claim social deprivation after years of having a dominant position in the caste hierarchy. The loudest voice was that of Chhagan Bhujbal , an NCP leader and minister in the Eknath Shinde-led Maharashtra cabinet.

Days after the OBC rally, the district saw another major protest, this time by the Dhangar shepherd community, which currently receives 3.5 per cent reservation under the Nomadic Tribes (C) category. They have long demanded to be reclassified under the Scheduled Tribes category, which gets 7 per cent reservation.

The protest grew out of hand when some members allegedly vandalised the district collector’s office after government officials refused to meet them and accept their memorandum.

“When the Marathas were protesting and Manoj Jarange-Patil was on a fast, the entire government machinery, even the Chief Minister, descended in Jalna to try to placate them,” said one of the Dhangar protesters, speaking on condition of anonymity. “And here, when we are protesting, not even a single government official from the district collectorate wants to meet us.”

But Balasaheb Tarakh, a Maratha farmer from Antarwali Sarati, suggested that political machinations by OBC leaders were at play.

“Their leaders came to our villages and filled multiple cars with members from the OBC community to take to the rally. The Dhangars, Malis, all the others, they have nothing against us Marathas. They are being deliberately provoked,” Tarakh said.

In a controversial video, Jarange Patil is heard saying: “Layki naslelya lokan khali Marathyana kaam karave lagat ahe (Marathas are having to work under people who have no worth).

No more joint kirtans

On a Wednesday evening in Antarwali Sarati, villagers gathered in front of a temple ahead of an upcoming kirtan— a daily ritual of spiritual sermons and musical devotionals. A young boy proudly wore an iktara, a musical instrument, around his neck.

This evening’s crowd primarily consisted of Marathas, but resident Lahoo Ganpatrao Tarakh, 65, insisted that these functions transcended community boundaries. “Everyone attends these kirtans, Marathas and OBCs alike. We all live in harmony,” he said.

The platform in front of the temple was the same spot where Jarange-Patil had staged his hunger strike. “So many of our OBC brothers also sat for the protest supporting our cause,” Tarakh said. He claimed OBC villagers were absent from the kirtan since they “must be out on their fields”.

But those from the OBC community claim that the camaraderie is all in the past. They are angry with the Marathas.

At Dodadgaon, another village about 8 kilometres away, a small crowd gathered at a temple on a Thursday evening. All the people belonged to the OBC community. Dodadgaon is located right across the road from the Mandal Stambh, a first-of-its-kind monument set up by former MLA Narayanrao Mundhe to honour the OBC community.

“At this time, many of our villagers used to make their way to Antarwali Sarati for the kirtan. But we don’t want to go there anymore,” said sarpanch Bandu Munde.

Provocative social media forwards are doing the rounds on the phones of both communities. One depicts Dhangar community members on top of electricity poles protesting police actions. Another shows a government schoolteacher urging students to pledge support for Maratha reservation. The caption asks how a school teacher can endorse a caste.

Yet another is a clip from one of Jarange-Patil’s speeches from when he was touring parts of Maharashtra in November, addressing rallies to drum up support for his cause.

In this video, Jarange Patil is heard saying: “Layki naslelya lokan khali Marathyana kaam karave lagat ahe (Marathas are having to work under people who have no worth).”

Also Read: Six friends & an amorphous group of Marathas — the backbone of Manoj Jarange-Patil’s quota stir

‘Unworthy’

Jarange-Patil’s term ‘layki naslele’ (unworthy) hit hard for the OBC residents back home.

Sarpanch Munde, who had provided his land for parking during Jarange Patil’s Antarwali Sarati rally, was visibly disturbed. “What does unworthy even mean? What is he trying to say?” Munde asked.

Jarange-Patil subsequently clarified his remark, but his explanation did little to dispel the perception of a Maratha superiority complex.

I pay Rs 1 lakh a year as tuition fee. My OBC friend pays Rs 40,000. Why the discrepancy when we both come from humble backgrounds?

—Shivraj Jarange-Patil, son of Manoj Jarange-Patil

“What did I say wrong?” he asked. “Our situation is now such that our educated are unemployed. Despite being intelligent, we are not able to work per our standards. Our educated today are suffering. Everyone agrees. Just don’t give it any caste or colour. Show me one instance where I have been casteist. I cooperate with every caste and religion,” Jarange-Patil said.

Data indicates that Marathas are better educated than OBCs, Scheduled Castes, or Scheduled Tribes.

According to a 2021 research paper by Sumeet Mhaskar, a professor at OP Jindal Global University, 22.88 per cent of Marathas are graduates, compared to 18.74 per cent, 19.24 per cent, and 7.87 percent of OBCs, SCs, and STs respectively. At the top are Brahmins and other upper castes, with 34.48 per cent and 36.41 per cent, respectively, being graduates.

Members of the Maratha community in Jalna argue that they struggle to access good quality, affordable education.

There is some irony in this situation. Mhaskar notes that influential Marathas control more than 50 per cent of the state’s privately managed engineering and medical colleges. The fees tend to be “exorbitant”, which means that Marathas of modest means have to rely on public institutions where seats are in short supply. “(T)hey see educational reservation as a solution to the crisis,” Mhaskar writes.

The plight of Jarange-Patil’s son, Shivraj, is an example of this struggle.

He said he aspired to study computer engineering at a reputed college in Pune, but his marks weren’t high enough to earn him a general category seat.

Shivraj Jarange-Patil ended up enrolling at a Jalna college run by the Tope family’s trust, Matsyodari Shikshan Sanstha. His father had to take a loan to fund the expensive computer engineering course.

“I pay Rs 1 lakh a year as tuition fee. My OBC friend pays Rs 40,000. Why the discrepancy when we both come from humble backgrounds?” Shivraj asked. He made it a point to add that his OBC friend agrees with him.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)