Rohtak: As soon as Akhil Kumar, Assistant Commissioner of Police, Traffic at Jhajjar, got off the phone after a meeting with top cops, he set aside his neatly penned notes and opened his iPad. On the screen was a live feed from his boxing academy in Hisar. “Do not sit idly, get up and train!” he said into the mic. The former Olympian and Commonwealth boxing champion’s booming voice is a cue to his students gathered at the boxing ring to start training for the day.

43-year-old Kumar has settled down as a police officer post-retirement but has not surrendered his love for boxing. He wakes up at 5 am every day to monitor his academy remotely. He sends extensive training notes via WhatsApp, keeps a constant check through the CCTV cameras, and intermittently gives instructions like Bigg Boss—he is never far away.

Gone are the days when international medalists in Haryana led a poor life. A medal still doesn’t guarantee endless wealth and fame, but it does come with stable government jobs and respect in society. And for those who did not reach the Olympic podium that’s more than enough.

An Olympic medal is also a ‘ticket’ to politics for wrestlers and boxers from the state. While Sushil Kumar languishes in jail, his medal-winning colleagues Bajrang Punia and Yogeshwar Dutt have entered the ring of politics. So has boxer Vijender Singh. Other popular athletes Gita and Babita Phogat, and Vinesh Phogat, who aren’t Olympic champions, are also active politicians. But not all of them are cut out for politics. Many just head straight to the lowest-hanging permanent government job.

For me, wrestling coaching was not just about medals, it was also about training my students to get government jobs, to light up a stove at their houses.

– Coach Ranbir Dhaka

Kumar is among the hundreds of athletes in Haryana whose post-retirement lives are spent away from the limelight. Most Indians will never know the ticket checker on their train has represented the country on the international stage.

Sports analyst Charu Sharma highlights the brutal and extremely competitive nature of contact sports where the risk of injury is high and often career-ending. “This means only the very best succeed, only 0.1 per cent of people, and they’re able to make some sort of a career. Through sport, many are able to find some sort of employment, but they seldom make it to top boss positions,” he told ThePrint over the phone.

Sharma emphasised that extensive counselling of sportspersons is necessary so they can understand and settle down for a low-wage structure in life. Veteran coach, Ranbir Dhaka also highlighted the importance of jobs in Haryana’s boxing and wrestling rings, where students often come from humble backgrounds.

“Haryana’s sportspersons, especially those in combat sports, come from humble backgrounds. For them, taking up the sport is also a means of landing a stable job. And many world champions, Commonwealth and Asian Games winners, those who represented India at the Olympics are doing just that,” said Dhaka, a retired coach from Rohtak. “For me, wrestling coaching was not just about medals, it was also about training my students to get government jobs, to light up a stove at their houses.”

Also read: No games, medals, opportunities for fame—Haryana wrestlers lost without entering the ring

Easing into retirement

Pinki Malik, the 2016 Commonwealth champion in freestyle wrestling, is now gearing up for her last match. Her eyes are set on gold in the National Championships, scheduled for later this year. But the gold medal is not her ultimate goal anymore. It is just a means to an end—a coveted promotion in the railways, from a deputy ticket-checking inspector to a ticket inspector.

After an illustrious career spanning 18 years, Malik is easing into retirement. Instead of waking up every morning at the break of dawn and heading to Rohtak’s Chotu Ram stadium where she trained under legendary coach Kuldeep Malik, she now gets up, wears a black blazer and hops onto the train heading to Delhi from Bikaner. It’s a demanding job with nine days of continuous work and just one day of leave. She hasn’t been able to visit any of the majestic castles in Rajasthan, there’s simply no time.

A majority of athletes, like Kumar and Malik, spend their retirement years serving on the railways and in the police. But the love of the game never really leaves their heart. They still dream of waking up early in the morning to sweat it out.

I have seen my coach Kuldeep work so hard through the years and train so many wrestlers, but it is a thankless job. I don’t want to coach students looking at his struggle

– Pinki Malik, wrestler

“Jis kaam se pehchaan hai, ussi ke paas rehna chahiye (One should remain close to the work they’re widely known for),” Kumar said. While his stature within Haryana Police affords him and his family a comfortable life, he remains under-confident about his skills as a cop. “I am not very well-read. I took up sports because I wasn’t very good at studies,” he said with a tired smile.

But Kumar never misses a day of work. His training as a sportsperson also gives him a rather relaxed demeanour. He addresses his subordinates as ‘bhai’ (brother) and seeks to bring an egalitarian approach to his police work.

While Kumar gives back to society through his academy, Malik eventually wants to train athletes within railways. But she doesn’t want to become a coach.

“I have seen my coach Kuldeep work so hard through the years and train so many wrestlers, but it is a thankless job. I don’t want to coach students looking at his struggle,” she said.

Malik is happy to settle down and start a family. She got married in 2021 to a family of coaches. Her husband, father-in-law, brother and sister-in-law are all coaches of various sports.

“I have had a successful career and now I am settling down in my job. I come from a small village and this job is very important to me. I have no complaints,” she said.

Also read: Haryana Khap has come a long way for women in 2 decades. Only for the medal-winning ones

‘Thankless coaching’

Ranbir Dhaka served as a coach with the Sports Authority of India for 35 long years. He turned to coaching when a ligament tear cut short his career as a wrestler. Most of his days were spent at the Mehar Singh Akhada in Rohtak.

Before his coaching career picked up, Dhaka competed in the circuit in the 1980s and made it all the way to the world championships.

After competing at the World Championships (1986) and Asian Games (1985), Dhaka called it quits and started working as a CISF constable. But the akhada kept calling him back, so he left his high-paying government job after six years and dived into coaching.

“Many of my colleagues retired as Superintendent of Police from CISF. I could have led a cushy life, but I just couldn’t give up wrestling,” he said.

Manoj Kumar, a boxing gold medallist at the 2010 Commonwealth Games opened a coaching centre in Kurukshetra in 2022. He runs the academy with his brother, whom he considers his coach. He spends his time touring with his team to various competitions. “We wish to create a legacy,” he told ThePrint over the phone from a competition in Visakhapatnam.

Coaching allows athletes to create a legacy, and elevate their status in society. A lot of sportspersons keep an eye on the coveted Dronacharya Award—a sports coaching award from the Government of India. And with academies coming up in various towns and districts, coaching is fast becoming a viable career option.

Many of my colleagues retired as Superintendent of Police from CISF. I could have led a cushy life, but I just couldn’t give up wrestling

– Coach Ranbir Dhaka

Dhaka is also a recognisable face in Rohtak, dearly called coach sahab. He is invited for ribbon cutting and foundation laying ceremonies by the city’s residents. When he retired, his students came together to gift him a KIA Seltos, a Honda Activa, and close to Rs 20 lakh in cash. They wanted to ensure that coach sahab led a comfortable life.

A 5ft 6, Dhaka is relatively short but still commands any room he walks into. To reign in the unruly wrestlers, he holds no punches. When he took charge as the coach at Mehar Singh Akhada, there were only seven students. Gradually, Dhaka and his team expanded the wrestling school. It currently has 1,500 students.

Wrestlers trained here have gone on to represent the country at the Olympics, and won medals at world championships, Asian Games and Commonwealth Games. And Dhaka has travelled the world with them, but only in spirit—he was never allowed to go on international tours. Sports Authority of India coaches were sent instead.

For Dhaka, the akhada and its mitti (mud) are a temple. Though his workout routine has mellowed down from 1,000 burpees a day to morning and evening strolls in the park with neighbours, Dhaka still oversees the workings at the wrestling school.

I always wanted the Dronacharya Award. I applied for it many times, but these awards are only given to people who have good political connections within the federations.

– Coach Ranbir Dhaka

Dhaka’s influence on the world of Haryana’s wrestling and the Jaat community also saw him rise to the occasion when wrestlers staged a protest against sexual harassment in New Delhi. Dhaka was present at the protest site every day. He was among the seniors who advised the athletes against immersing their medals in the Ganga.

For all his hard work and influence, Dhaka has not been recognised by the Indian government—the Dronacharya Award remains elusive to the 70-year-old. It would be the final feather in his cap.

“I always wanted the Dronacharya Award. I applied for it many times, but these awards are only given to people who have good political connections within the federations, I never did. This year I have applied again but now that I was a part of the protest, I don’t think I will get it,” Dhaka said with a sense of defeat, while sipping green tea on the lawn of his house, located just outside Rohtak.

But Dhaka has no regrets. For him, the greatest achievement is that he has helped more than 600 families find employment during his tenure. “Only a handful of students are able to win medals. Unfortunately, a lot of wrestlers also turn to crime. But the biggest satisfaction is that we have trained countless students and seen them start families with stable government jobs, I am most proud of that,” Dhaka said.

He said that many wrestlers have gone on to work in railways, police, and some have opened businesses. “Majority of them work as property dealers,” said Dhaka.

But opening academies is not an easy task. Acquiring land for an extensive academy is difficult to begin with, and then comes the investment. Olympic bronze medal winner Yogeshwar Dutt opened a sprawling academy at Ghilor Kalan in Haryana, and Sushil Kumar used to oversee training at Chhatrasal stadium in New Delhi before his arrest. But Olympic medals open doors, they give athletes more influence and means to start these ventures.

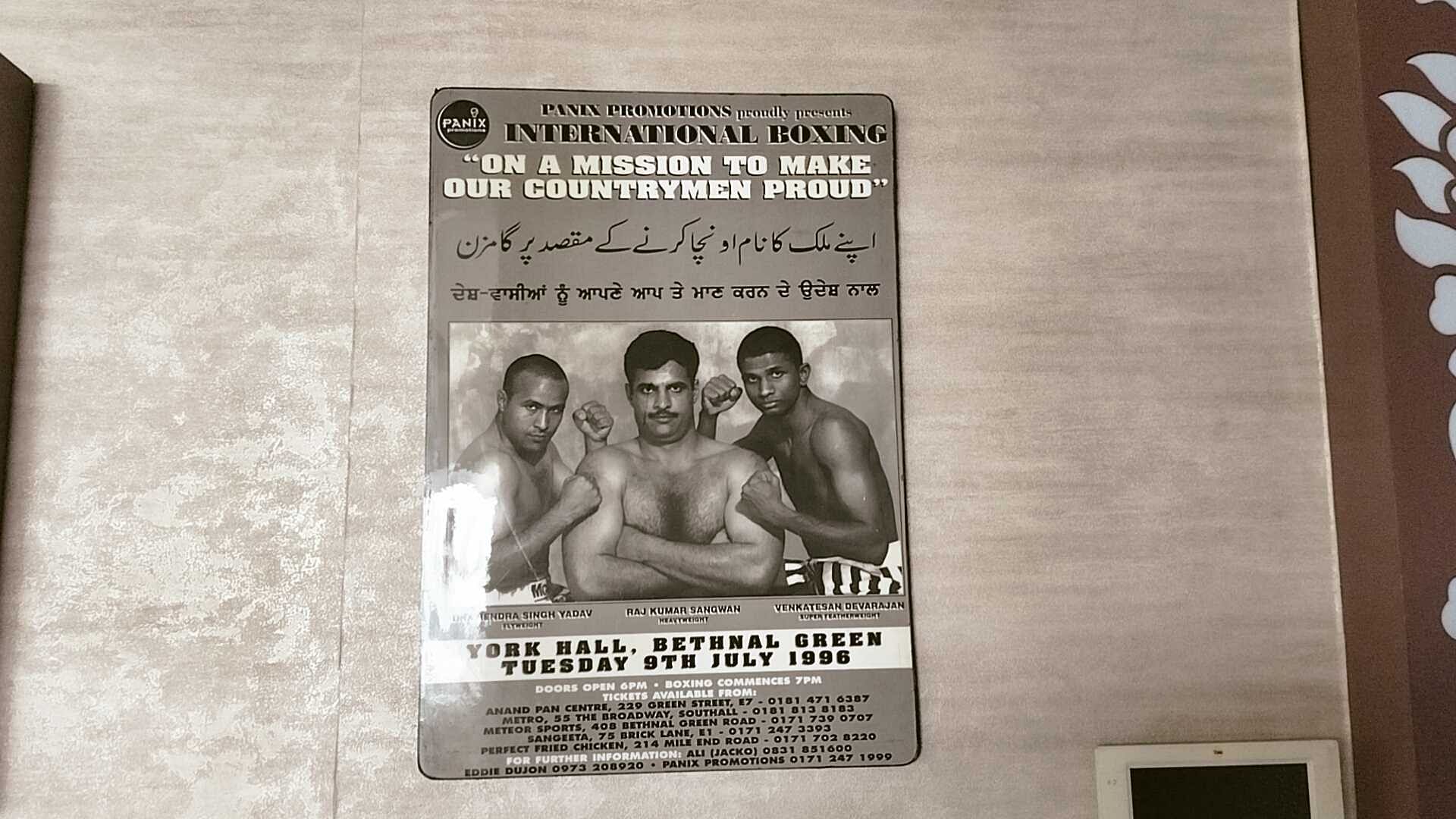

In the early 2000s, Asian games champion Raj Kumar Sangwan opened his own boxing academy. It ran successfully in Delhi’s Kendriya Vidyalaya Sainik Farm till 2014. But due to paucity of funds and ‘heartbreak’ he had to shut it down.

I suffered heartbreaks. Many ace boxers who had trained under us gave us no credit. I didn’t want to be in this thankless coaching job

– Former boxer Raj Kumar Sangwan

“We charged fees that covered only our running cost, which included the staff’s salary, electricity and rent, but there’s no profitability in the academies. Athletes come from poor backgrounds and we can’t charge them more,” Sangwan said at his home in Gurugram.

At his academy, Sangwan trained many promising boxers including Sumit Sangwan, Balbeer Singh and Praveen More. But many athletes soon forgot about their school once they gained credit, Sagwan said.

Sangwan had to struggle to get recognition. His move to open a private academy had miffed a lot of professionals at the Sports Authority of India, he said. And he was overlooked for the Arjuna Award. He then approached Delhi High Court to get his due. The matter was settled out of the court and he got the award in 1997.

“I suffered heartbreaks. Many ace boxers who had trained under us gave us no credit. I didn’t want to be in this thankless coaching job,” he said.

Also read: ‘Wrestlers have to manage on their own’ in India—What Dara Singh told Nehru

Entering the federation

Another natural transition for athletes post-retirement is sports administration. It is a space reserved for more ‘successful’ athletes. They’re aware of an athlete’s needs, and precisely what needs to be done to improve the sport. But red tape and politics make some averse to the idea of federation politics.

“Sports administration is not easy. Some of us think if we enter the federation, we can bring change from within. But it is not worth it, you need to be good at cultivating political connections,” a retired athlete said.

Sangwan served on the ad hoc committee for boxing for 10 years, lending a hand to the selection process, but eventually left as he got tired of the politics. Sangwan tasted success in the sport when it was extremely rare—he won his first gold medal at the Asian Games in 1991.

Sports administration is not easy. Some of us think if we enter the federation, we can bring change from within. But it is not worth it, you need to be good at cultivating political connections

– Retired athlete

As a 13-year-old, his eyes lit up when he saw Amitabh Bachchan facilitating 1982 Asian Games champion Kaur Singh. Then an active member of the National Cadet Corps, Sangwan decided then and there that he too wanted to pursue sports as a career and stand on the world’s biggest stages.

It was almost as if the universe conspired to make Sangwan’s dream come true. When he joined a college at Bhiwani, he signed up to be part of its college boxing contingent—and he was the lone applicant. Sangwan trained at Bhiwani stadium under coach RS Yadav.

Eventually, the legendary Captain Hawa Singh took over the facility and provided sophisticated training to many young sportspersons there, including Sangwan. Captain Singh gave wings to Sangwan’s dreams. “He used to tell me I would sit in an aeroplane one day,” Sangwan remembered.

Sangwan peaked at an international ranking of number four, the first for an Indian boxer.

“Back then we hardly had any facilities. Our gloves were made of jute, and we used to cover our hands with crepe bandages underneath them, instead of a boxing hand wrap, and play with canvas shoes!” Sangwan said.

At his home in Gurugram, Sangwan proudly displays his many achievements including the Arjuna Award, a poster of a 1996 boxing league match in the United Kingdom. He later went to the United States to train in professional boxing and learn the business of boxing.

But Sangwan gave up professional boxing and returned to India in 1996 to start a family.

In the early 2000s, Sangwan worked with IOS, a sports agency, to start a professional boxing tournament in India. In 2005, long before the Indian Premier League had been conceived, Sangwan hosted a private boxing tournament at Delhi’s Ansal Plaza Open Air Theatre. They pitched five Indian players in front of five International Players—one of them was Vijender Singh.

Now he spends his time on news channels as a sports analyst and runs an advocacy group for Arjuna Award winners.

“It is important to remember our sports stars, to learn from them, and improve with the help of their experience. But we forget them and ignore them,” he said. “To become better at sports, retired sports persons need to be celebrated, commemorated.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)