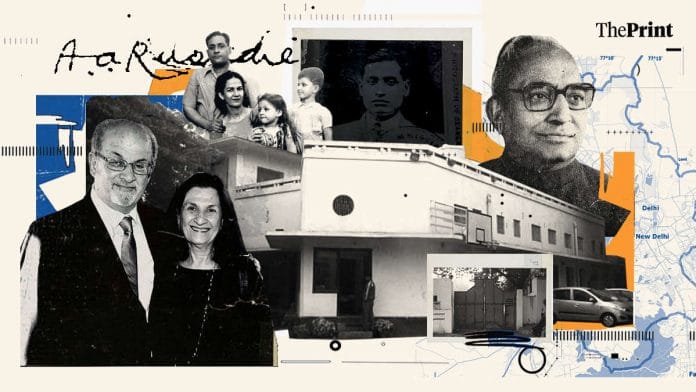

New Delhi: Narendra Jain has been displeased for decades—with equal parts loved and loathed author Salman Rushdie. The politician-cum-businessman doesn’t have much in common with the New York-based novelist, who is currently working on a memoir after being stabbed at an event. Except, technically, the Rushdie family owned the Jain bungalow—their unassuming, single-storeyed home, located on a quiet street in Delhi’s Civil Lines.

The house in question, 4 Flagstaff Road, with its sun-soaked front lawns, has been mired in a complicated legal battle ever since Salman Rushdie’s father ‘sold’ it to politician Bhiku Ram Jain for Rs 3.75 lakh in 1970. And, as of last week, the Delhi High Court set aside the house’s previous valuation of Rs 130 crore, and declared that it be valued afresh. Jain declined to comment on what he thinks this sum will be, saying that they were waiting for the court to decide.

Today, it is the residence of Jain’s brother Arvind and his wife. They’re currently renovating, and the metallic smell of paint is in the air.

Jain treads carefully into the drawing room, where the couches are covered. It’s dimly lit, brought alive by a single orange wall—the wallpaper consists of an assortment of deer and peacocks.

“All of this has been done by us,” says Jain, pride in his voice evident.

Also read: ‘Bogus deals, fake will’ & a landlord named Rushdie — curious case of Delhi HC’s ‘oldest’ civil suit

Where it all began

The ‘tryst’ with the Rushdie family began in 1970, with their fathers. Congress politician Bhiku Ram Jain’s family was expanding, and he needed a home. His neighbour Najja Ram Kapoor, a property dealer, introduced him to Anis Ahmed Rushdie, Salman Rushdie’s father. Anis spent most of his time in London and was only too keen to rent out Flagstaff Road’s Bungalow Number 4.

But in the 53 years since it was ‘sold’, a lot has happened.

Salman Rushdie has written several bestsellers, won the Booker Prize, received a fatwa, and has been married three times. Narendra Jain has switched political parties three times, and lives on the road adjacent to Flagstaff Road, named after his father Bhiku.

While Rushdie has been preoccupied by the perils of writing fiction, Jain has been consumed by various courts across Delhi in an endless legal battle with a family that barely exists to him.

“From 1970 to 2023, not a single member of the [Rushdie] family has come here. The territory of India has not seen the blood of the Rushdies,” declares Jain. “And we’ve gone through the entire rigmarole of trying to get in touch with them.”

Their medium of communication has changed, but whether it’s a letter or an email, the subject remains the same. The Jains want the Rushdies to acknowledge the 1970 sale of the house, and pronounce them as owners. Narendra Jain has called, texted, messaged Rushdie on Facebook, and even tracked down his daughters in the US and UK—only to be met with a stony silence.

Even as they live their lives, the case lingers on in the background. In 2012, the Supreme Court asked the Jains to pay the bungalow’s current market price—anywhere between Rs 80-100 crore.

“I told them—sir, I’m ready to pay Rs 6 crore to buy peace. It’s been 40 years of litigation. My father has passed away. We will also pass away. And then this property will just be lying there. We have to settle someday,” says Jain.

Also read: Salman Rushdie trapped by alliance of implacably regressive and insufferably progressive

Two families, one home

Bungalow Number 4 is not a house past its prime. Constructed in 1908, it’s been meticulously maintained. According to Jain, it originally belonged to a colonial-era commissioner. He marvels at the house’s sturdiness, airy rooms, and high ceilings. The fans are old-style, suspended high up. There aren’t too many windows. One room is completely enclosed, except for a small opening in one corner.

It’s an ordinary home. An anomaly only because Flagstaff Road consists largely of mansions in various shades—the glass and wood-panelled palatial residences, and the older, larger kothis. What further wrests it into the background is its powerful neighbour. Right next door lives Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal. Policemen are swarming, and the Jain/Rushdie house isn’t high on their priority list.

However, it’s still the core of the Delhi High Court’s oldest civil suit.

In the backdrop of the legal quagmire, Narendra Jain and his four brothers got married in the front garden—a long, relatively narrow expanse of green. They had 15 children, 12 of whom have been married in the same lawn. There’s a canopy of trees in one corner, lush grass in the other.

“We have so many parties there. New year’s parties, Diwali parties, family functions, weddings. That’s the most wonderful part. It’s one of our rituals,” he says.

The 5,373 square yard estate is divided by a hedge, on the other side of which live the Chand family. Walking along the driveway, Jain points to a particularly weathered portion—that’s where he and his brothers used to play badminton.

Jain says he was witness to the agreement between his father, Bhikhu Ram, and Anis Rushdie, in the same garden. That was over five decades ago.

Rushdie’s father died in 1987, and Jain’s father in 2005. Among other things, Bhiku Ram Jain passed down to his son the case—traversing various courts in the city, dealing with the emergence of a reportedly fake will, “interlopers”, and, according to Jain, even a fake buyer.

But the palatial lawns and the building that was constructed over a century ago aren’t worth much now, he argues. The property can’t be developed or redeveloped, and no subdivision can take place. “I wouldn’t buy it. We can’t develop it, we can’t divide it. I want to buy peace,” says Jain. “The property has no value.” It can be torn down and made into a mass of builders’ flats, owing to the floor-to-area restrictions in Civil Lines.

What frustrates him even more is that whatever the property value is, it would be a “paltry sum” for Rushdie. “He’s the author of The Satanic Verses. He’s a global celebrity. What is money to him?”

Also read: It wasn’t easy to support Salman Rushdie in Bangladesh. Then I realised fatwas are contagious

Handcuffed to history

Jain is certain that it’s a lack of generosity on Rushdie’s part—“small-mindedness”. Over the past many years, the case has found its way into the news cycle—largely because of the Rushdie connection. Headlines always mention him. How could he not know, Jain asks.

It might be argued that the Haroun and the Sea of Stories writer, while extremely high-profile, has also been preoccupied with the travails of his own life. It was only last year that he lost an eye, after being repeatedly stabbed at an event where he was set to deliver a lecture.

For his disgruntled ‘tenant’, though, it was written in the cards. “He was stabbed nine times. It was destiny. It happened to him because of what he has done to me.”

While India features prominently in several of Rushdie’s books—he has previously referred to the country as his “greatest inspiration”—he doesn’t appear to be as enamoured with Delhi as he is with Mumbai, the city of his birth and central character in Midnight’s Children. His latest novel, Victory City, focuses on the 14th century Vijayanagar Empire.

In Midnight’s Children, Rushdie’s Saleem Sinai says: “We are handcuffed to history.” In Jain’s case, this is partially true. He’s bound to where his history is situated—within the confines of a nondescript white building, the place where his family lore has unfolded.

It’s now his ancestral home. The place that witnessed his father’s legacy, and where he is building his. And according to him, property, litigation, and money go hand in hand. “It’s a matter of concern, of course. But everything is,” he says.

As for Rushdie, he may have legions of fans spread across the globe, but Narendra Jain—the 4 Flagstaff Road’s long-suffering tenant—is not one of them. “I’ve never read any of his books,” he scoffs.

(Edited by Prashant)