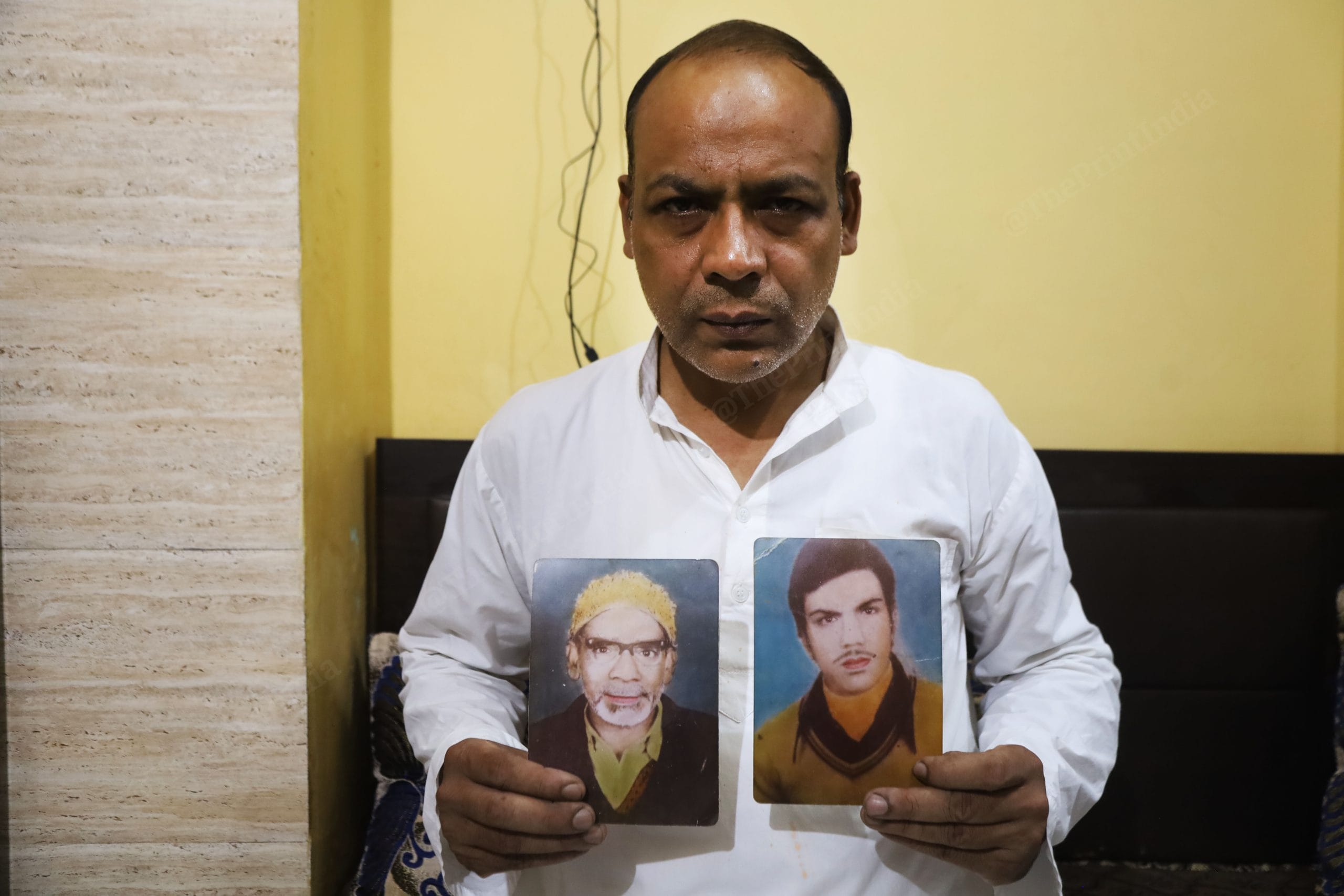

Moradabad: In 43 years, Nazim Hussain has visited several mortuaries and at least seven jails in Allahabad, Bareilly, Mumbai, and Hyderabad looking for his father, his two older brothers and a family domestic worker. “We even went to the jail in Andaman and Nicobar,” said Hussain, who was barely seven when the police dragged the four men from their house in Moradabad’s Galshahid Mohalla on 13 August 1980.

Now, the memories of the Eid riots locked away in the attic of his mind for over four decades have become a deluge, tumbling out one after the other.

The police, the smoke, the tear gas, the tears.

Within hours of a violent action by the local police against the Muslim community outside Ek Raat Wali Masjid over a pig, the police knocked on Hussain’s doors between 11 am and noon. They dragged his father Haji Anwar Hussain, his brothers Sajjad and Kaisar, and domestic worker Abdul Salam into a police vehicle that melted into the smoke. Their backs were the last he saw of them.

The indiscriminate firing by the police on Muslim worshippers that killed hundreds of people, including children, remained in news until 1983 — and then there was complete silence. Local political leaders from the community who rose over the years distanced themselves—until May 2023. That’s when Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath announced that his government would table the Justice MP Saxena report in the state assembly. The report had given a clean chit to the police.

Justice Saxena had given a clean chit to police brutality. What happened to my father, my uncles, and our worker?

“My Abbu was shot,” says one long-time resident of Eidgah, located in the heart of Moradabad. People have been gathering over the day in listless agitation talking to journalists, television reporters and activists who have returned to the scene of the tragedy.

“My younger sister lost my hand and got stampeded,” says another person. They are the keepers of the memories, burdened with the responsibility of finding the fate of their loved ones. And now that the country’s gaze is back on Moradabad, they all want to be counted.

“My brother was picked by the police and never returned,” a third voice emerges. They are the last generation of teenagers and children—now in their 50s, 60s, and 70s—who bore witness to the events of that Eid.

Haji Anwar Hussain’s family rejoiced when CM Adityanath announced its decision to table the report. They hoped for closure. Instead, it has ripped open their unhealed wounds.

“Justice Saxena had given a clean chit to police brutality. What happened to my father, my uncles, and our worker?” said Nazim’s nephew Faheem Hussain. He was a child when his father Sajjad Hussain was taken away by the police.

The language used [in the Justice Saxena report] against ordinary Muslims is so dehumanising. You carry your children and elderly to plan riots?

Also read:

The dreadful night, a never-ending wait

The area around Eidgah still bears the scars of the violence—charred walls, smoke-blackened roof edges, hastily patched bullet holes. The local police station that was burnt down by the mob has been rebuilt, but not the homes around it.

The greyish-green door of Haji Wasim’s (60) house is still pockmarked with bullet holes. It is now a storeroom for his grocery shop, filled with tins of besan, packets of Surf Excel, and bottles of cooking oil. Kittens scamper around the piles of groceries, while their mother, a ginger cat, lazes on the floor.

Haji Wasim’s mother Jamila Khatun was allegedly shot by PAC when she was hiding in one of the rooms along with her four children. After shooting her in her arm, the PAC opened fire in the courtyard.

The four children remained terrorised, peeking from the wooden door. Some of the blackened spots on the roof edges due to flames are still there.

“Her dead body lay in the courtyard for three days but we weren’t allowed to bury her. An MP from Rampur Mikki Miya got to know about the case, and he arranged for curfew passes.” Wasim recalled.

He said that before the family could prepare for the last rites, the PAC came and took away the body for postmortem.

“We never got the body and we couldn’t bury our mother,” Wasim added.

A few metres away is Nazim Hussain’s family house. The patriarch, Haji Anwar Hussain, had locked and barricaded the doors. Children, aunts, uncles and elders sat quietly in a room—waiting.

Outside, the police and the Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) were on the hunt for the rioters.

The Hussain family recalls the sound of boots and shots being fired coming from the street outside. Suddenly, there was a knock.

“Open the door,” Nazim recalled a PAC jawan shouting and another voice saying, “We have to search your house.”

Nazim’s sister-in-law Sajida Begum picks up from where he left off. She remembers an “army of angry jawans” barging into the house.

They dragged four members into the waiting police vehicles.

“They were without slippers. We could see their backs. We kept crying,” said Sajida Begum, who is in her 70s now.

For several days, the family kept vigil in the local mortuary thinking the worst had happened. They have not celebrated “Meethi Eid” [Eid-Ul-Fitr] since then. Every 13 August, relatives meet to mourn the missing men.

Our father would have been in his 80s today. Every time we see a man that age, we become hopeful.

For many families, what happened to Muslims in Moradabad on 13 August 1980 is still a mystery.

Thousands had congregated outside Ek Raat Wali Masjid for Eid celebrations and prayers. There were stalls, posters for 788-brand bidis, and bright banners for shops selling sweets and toys.

A rumour started to gain ground that a pig had entered the area. It sparked anger, and many reportedly started throwing rocks and stones at the police outposts. Additional District Magistrate DP Singh was beaten to death by a mob. Four police constables—Dhirendra Singh, Haridutt Pant, Magananand, and Parsadi Lal—died. The fact-finding Saxena report cleared the police for its use of excessive force. It noted that all 34 who died in the initial melée were crushed in a stampede, not shot.

But it doesn’t answer Faheem’s question: “What happened to my father? My uncle? My grandfather?”

He is now 50, and cannot give up hope. He looks for his father in every elderly stranger that crosses his path.

“Our father would have been in his 80s today. Every time we see a man that age, we become hopeful.”

Independent India’s ‘Jallianwala Bagh massacre’

In the days following the violence, politicians came, made promises and left. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi addressed the events in her Independence Day speech two days later.

Faheem’s family has witnessed 15 chief ministers and all political parties, including SP, BSP, Congress, and BJP, come to power, and yet no one has acted on the promise that Indira Gandhi made to his mother Sajida on 16 October 1980.

Sajida remembers leaning on Gandhi’s shoulders while crying profusely.

“When she gave me some paper, I threw it and refused to accept any momentary help. All I asked from her was to find my husband and the family members.” Sajida said that the prime minister left with a promise to help her in finding her husband.

The family vowed not to vote for the Congress ever again and have stuck to it, as have several other Muslim families. In the 2019 Lok Sabha election, the party fielded a 32-year-old YouTuber, Imran Pratapgarhi, from Moradabad. He lost his deposit.

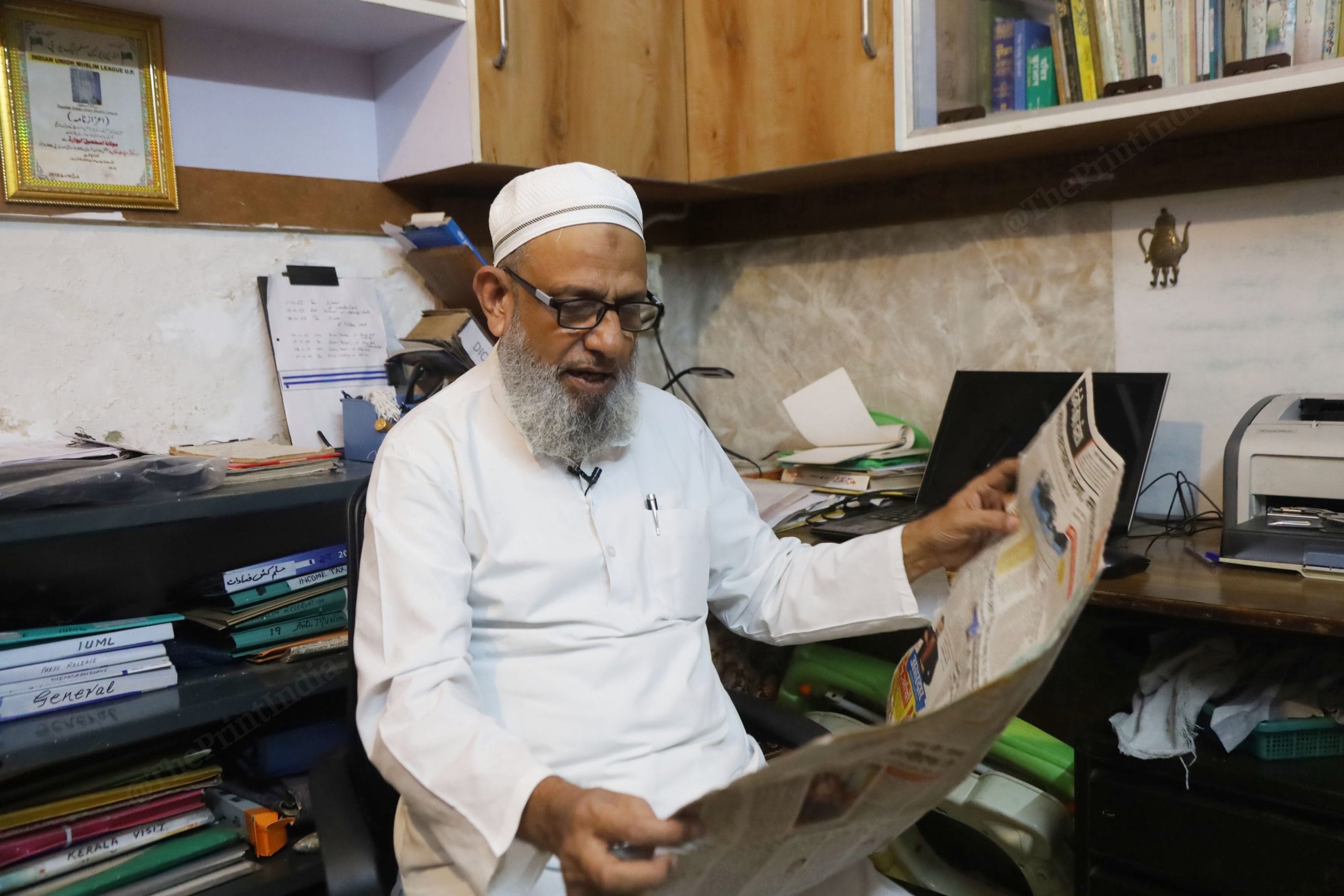

“Congress has used us as political pawns,” said Kaushar Hayat Khan, who was 27 years old at the time. He was a young member of the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), and now serves as its national joint secretary.

“When Sikhs were massacred in 1984, the governments formed commissions after commissions to heal their wounds and award compensation. Even the current government is trying to heal the wounds of Kashmiri Pandits and reopen the cases of their exodus. Why are Muslim lives considered cheaper?” Kaushar Hayat Khan said.

Advocate Ishrat Hussain, who is also affiliated with the IUML, said that he did not see the Jallianwala Bagh massacre but it must have been something like what he witnessed on 13 August 1980.

“I was 15 at that time and I sat down at the same location 43 years ago to offer namaz,” Ishrat said as he recalled standing on the Eidgah gate where the firing began.

A bullet hit the person sitting next to him. It was raining that day.

“Rain was pouring and so were the bullets. The man was bleeding from his stomach. I tried to lift him up but I had to run for my life as the firing led to a stampede,” he recalled.

BJP leader and former external affairs minister MJ Akbar visited Moradabad as a young journalist and wrote a book called Riot After Riot: Reports on Caste and Communal Violence in India.

According to the book, Moradabad was not a Hindu-Muslim riot but a calculated cold-blooded massacre of Muslims by a rabidly communal police force that tried to cover up its genocidal act by projecting it as a Hindu-Muslim riot.

Akbar is not the only one to document it in this manner.

On 18 August 1980, MP Syed Shahabuddin said in the Rajya Sabha: “the tragedy of Moradabad is nothing but Jallianwala Bagh re-enacted.”

Also read:

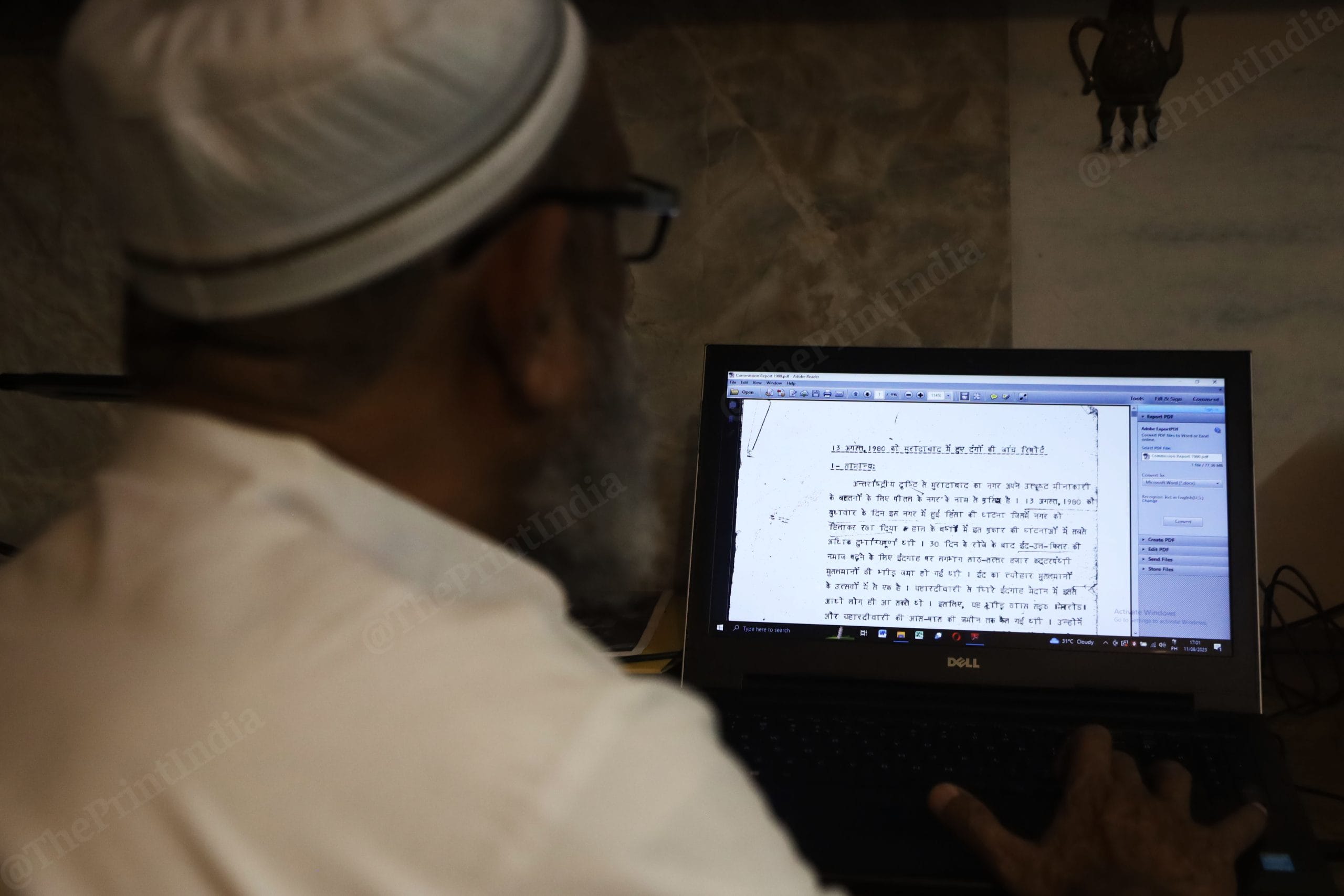

The ‘dehumanising’ report

The Saxena report concluded that there was no pig.

Justice Mathura Prasad Saxena submitted his report in 1983, but it has been neither accepted nor rejected by the subsequent governments. And though major newspapers and magazines like India Today published some of its details over the years, news never filtered down to the families in Moradabad.

Moradabad MLA and BJP leader Ritesh Kumar Gupta calls it a “historic” decision by CM Adityanath to make the 492-paged report public.

“It lay in one of the departments for the past 40 years and no one dared to make it public. Why? Because it tells you everything about who planned it.” he said.

It names two Muslim leaders as the masterminds.

“Behind the communal massacre (of 13 August 1980) was the power of the Muslim League and the khaskars who were led by Shamim and Dr Hamid Hussain alias Ajji,” the report says, while pulling up the police for failing to quell the tension rising in the area.

It further says that Shamim Ahmed Khan, “whose political ambition was too high, had revived the Muslim League in UP,” and was desperate to regain influence over the community after a series of political losses.

“A crowd of 60 to 70 thousand radical Muslims gathered at the Eidgah to offer Namaz,” the third line of report reads.

However, the victims’ families have rejected the findings, and are angry about being painted as extremists.

“The language used against ordinary Muslims is so dehumanising,” said Hayat Khan.“You carry your children and elderly to plan riots? We have never said that it was planned by BJP or RSS but it was the police who carried out this massacre. The administration invented the Hindu-Muslim conflict to give themselves a clean chit. The Congress government was behind it,” he added.

Shamim Ahmad parted ways with the Muslim League in 1988. He later joined Janta Dal. In 1989, he became an MLA and was given the rank of state minister.

“He got the red batti and never bothered to voice for the victims of the 1980s,” Khan said.“This was a police vs Muslim. It was never a Hindi-Muslim conflict. The police made it so to save themselves from the atrocities they committed,” he added.

Also read: ‘I haven’t shown the video to kids’—wife of train shooting victim now shows Aadhaar as shield

It’s election time

Once again, Moradabad is in the public gaze. It’s not just journalists but local politicians as well who have been visiting Muslim families in the area.

Almost everyone stops by at the Hussain family’s house. Sajida waits anxiously wondering if the strangers who keep coming know anything about what happened to the men. Will someone tell her that her husband is dead? Or perhaps he is still alive?

Faheem and others are more cynical. The media and the politicians will stop coming, just like they did in 1980. Everyone’s in election mode right now.

Outside, the sky above the Eidgah is dotted with kites—kites bearing the colours of the Indian flag flutter gaily as children wield the strings and reels, waiting for that perfect gust of wind.

But the young children in the Hussain family are at home, quietly listening to their elders re-live the nightmare. The walls of the house do not have any photos of the family patriarch and the other missing men.

“We never told them what happened. And now they ask, why didn’t we tell them about what happened to their grandfathers,” Faheem said.

(Edited by Prashant)