New Delhi: Meena Mandilwar died in 2015, but her presence lingers everywhere in the sunlit home of 88-year-old Kali Prasad Mandilwar, who lives alone in Delhi’s posh Vasant Vihar. Meena’s paintings of landscapes and portraits of women hang on the walls, along with photos of her smiling radiantly beside him. They keep him company, even though he has learned how to live alone, without his partner.

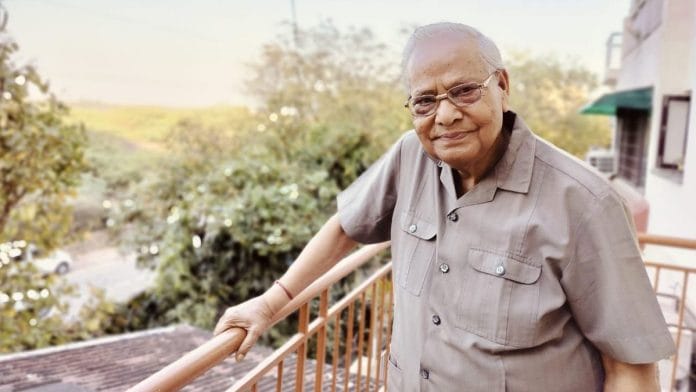

“After she died, I didn’t know what to do with my life. I used to sit in front of the temple and ask the gods to end my life. I was deeply depressed,” said Mandilwar, known to most as KPG, while gazing at the JNU forests from his spacious balcony. “Look at this… so beautiful. But it was even more beautiful with her around,” he added with a smile.

Over the years, KPG, a retired Indian Oil executive, has built a new life in solitude. His schedule is now his best friend, with every day logged to the minute in his diary. He lives for Meena to this day, learning and embracing activities that made her happy. He has taken up painting and cooks using the recipes she jotted down in diaries. But he’s not living in a vacuum—he has also found a new network of social connections on Emoha, an app designed to help older adults cope with loneliness.

In a world that deprioritises those who exit the economically productive years, loneliness can hover like a dark cloud over time-abundant days. The ‘golden years’ often begin to feel grey. The Longitudinal Study of Ageing in India (2018) found that 13.4 per cent of people over 60 reported frequent loneliness. Other surveys report much higher rates. A 2022 survey by PAN Healthcare, for instance, found that 65 per cent of 10,000 respondents across 10 cities said they felt lonely.

The fallout isn’t just emotional. Loneliness increases the risk of dementia by 31 per cent, according to research by the US National Institute on Ageing. In India, around 8.8 million people over 60 have dementia, or about 7.4 per cent of that age group.

There are certain conversations one cannot have with family because you don’t want them to worry or to off-load everything on your loved ones

-Vibha Singal, founder of Sukoon Unlimited

A loss of a sense of purpose, declining health, and too much unstructured time come together to make a morbid cocktail—one that makes loneliness in older adults more vicious and complicated than it is for the rest of the population.

While there hasn’t been a recorded rise in trained geriatric therapists in India, the growing ‘silver economy’ has seen a wave of private players and apps stepping in to fill the gap.

A subculture of seniors seeking friendship and community is booming. HelpAge India has opened activity rooms across the country where the elderly can drop in and play indoor games. Emoha, an app where seniors can connect with others and join community activities online, is gaining traction. New ventures like Seniorshield are a one-stop shop for access to doctors, including mental health professionals. Sukoon Unlimited, a Bengaluru-based startup, runs support groups and offers counselling to elderly people seeking mental health support.

“There is a lot of social isolation for the elderly. They move from an independent life to a largely dependent one, from active to not-so-active—and that affects them psychologically. They lose a sense of purpose, self-worth, access to friends and social life, which leads to withdrawing from life completely,” said Dr Reema Nadig, group chief operating officer of Columbia Pacific Communities, which specialises in senior housing and also runs Seniorshield.

She added that hearing loss in advanced years can make isolation worse. “All these factors lead to depression, and depression is a risk factor for dementia.”

KPG’s friends in the colony have all died, one by one. On his society group, there are regular messages of citizens wishing ‘Om Shanti’ to departed souls. He has kept these groups on mute.

Also Read: Life inside India’s posh senior communities. Karaoke, cocktails, billiards, aqua aerobics

Beating loneliness online

“What really is forgiveness?” a counsellor asked during an online support group run by Sukoon Unlimited, a Bengaluru-based mental health startup tailored for the elderly.

The responses included forgetting, moving on, spitting out the poison. But one question came up again and again: It’s easy to forgive others, but is one to forgive oneself?

The group, attended by about a dozen people, convenes weekly with psychologist Sachitra Chakravorty. In this session, the participants, most in their 60s and 70s, spoke about unresolved traumas, asked for ways to cope, and looked to the therapist for answers. Some had tried spiritual healing with no success. Others compared the challenge of forgiving to climbing the Himalayas.

Chakravorty gave everyone a chance to speak, tell their stories, and voice their fears.

“Ask for forgiveness from yourself,” he told them. “Send love to yourself and the situation… It doesn’t matter what others do.” He ended the session with meditation and breathing exercises.

Sukoon was founded by Vibha Singal in April 2023. The idea came from watching her mother struggle after losing her husband to Covid.

“She had us, she had family, and we would have free-flowing deep conversations about what was going on in her head. And yet there are certain conversations one cannot have with family because you don’t want them to worry or to off-load everything on your loved ones,” she said.

Many older adults bottle up the emotions and thoughts that gnaw at them—feeling invisible, depressed, anxious, or terrified of dying alone. These feelings often show up in other ways, including physical symptoms.

Singal noticed that her mother’s grief showed up as illness, fatigue, and unexplained ailments. Emotional pain took physical form.

At the time, Singal was working in Singapore. She spent three years planning out the project before moving to Bengaluru and launching Sukoon.

“All mental health apps are made for younger people, who do not wish to speak to senior counsellors. On the other hand, on mental health tech platforms, seniors don’t find younger counsellors relatable. By bringing peers together, we are not only reducing stigma related to mental health among seniors, but also giving them more relatability,” Singal said.

In older patients one can sometimes see apathy, a loss of interest in doing activities, hobbies, or talking to people. In extreme cases, this can even lead to psychosis—they get hallucinations, start muttering to themselves

-Dr Mauni Nagda Bhalke, psychiatrist

Sukoon now provides online counselling, personal as well as group sessions. It also has ‘Sukoon Sarthis’—senior citizens who offer companionship on call. The Sarthis are not trained therapists but are selected after five rounds of ‘personality evaluation’.

“Sarthis are senior citizens who have high empathy levels, and strong listening skills. These are seniors who are teachers, bankers, insurance agents. The core role of Sukoon Sarthis is to act as your sibling, guide, mentor… whatever you need them to be,” Vibha said.

However, Sukoon is grappling with a dearth of experienced therapists. On its website, the company lists four counsellors but not all of them are trained psychologists with degrees. Two appear to have psychology degrees, while the others have certifications in life coaching, according to their LinkedIn profiles.

Meanwhile, a new app called Seniorshield, also based in Bengaluru, offers online therapy alongside shopping, medication reminders, and cognitive games. Unlike Sukoon, it has no age bar for therapists.

“It has nothing to do with the age of the psychologist. It has to do with the kind of psychologist it is. So when we select people, it is about what kind of quality they bring in. There are young people who bring in nice, bright ideas, which the elders can also connect to. It has nothing to do with age or maturity,” Nadig said.

While therapists and geriatric psychiatrists welcome initiatives like Sukoon, they also warn against relying on underqualified counsellors.

“These initiatives are great. A 60-year-old just reaching out and probably just conversing with the elderly, providing some kind of counselling will help,” said Dr Mauni Nagda Bhalke, a Mumbai-based psychiatrist who specialises in special care for patients with dementia, among other things. “But if you’re not well equipped, talking in the air, without experience, will not help.”

Late bloomers in therapy

When Mumbai-based Vijay Nallawala founded Bipolar India in 2013 as a peer support network, conversations on mental health were just picking up. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2004, he created the platform to spread awareness and build a supportive community. Its Telegram group now has 800 members from across the country, cutting across age groups and open to anyone dealing with mental health issues.

One of them is 68-year-old Kalpana Sadasivan. For her, the support group is a safe space for like-minded people to share the daily struggles of living with mental illness.

“I’m in that group as a person with depression and anxiety, and also as a caregiver,” she said. “Listening to the various conversations, I get to understand a lot more about various conditions. It is non-judgmental, empathetic, and sometimes, another person’s experiences helps me in my journey.”

More maturity and experience in life doesn’t necessarily make things easier. In fact, sometimes there is a higher level of difficulty, as there is a sense of urgency and the awareness that with the passage of time, there are changes in one’s body and mind but often our responsibilities haven’t really reduced

-Kalpana Sadasivan, 68

Based in Bengaluru, Sadasivan first encountered anxiety in her early 30s. Her marriage was crumbling, and she sought counselling to help her relationship. That experience was disappointing.

“Unfortunately, I cannot say that any of the doctors, psychiatrists or counsellors we contacted then helped in any way,” she said. “Much later, in my mid-40s, after I moved to Bangalore, I met therapists who helped me make sense of several puzzles in my life. I continue therapy, though sporadically, to help me deal with depression and anxiety.”

Sadasivan belongs to a generation that still hasn’t quite normalised the idea of therapy.

“I won’t use the word stigma, but I don’t see people of my age group seeking therapy,” said Visa Lakshi Sridhar, a former psychology professor at Montfort College in Bengaluru. “Very few people who are older, over 50, come for therapy. I had a few clients who were slightly older people, but I find them dropping out much more than the younger people.”

For many older people, it’s hard to overcome cultural conditioning against discussing personal matters with outsiders.

“They’re particular that family secrets don’t go out,” added Sridhar, who takes therapy now herself.

Sadasivan has been in therapy for years. But with age, she says, the experience of depression and anxiety has changed.

“More maturity and experience in life doesn’t necessarily make things easier,” she said. “In fact, sometimes there is a higher level of difficulty, as there is a sense of urgency and the awareness that with the passage of time, there are changes in one’s body and mind but often our responsibilities haven’t really reduced,” she said.

Bouncing back, she added, is more difficult “with all our faculties not being at their peak.” While she doesn’t describe herself as lonely and even enjoys solitude, anxiety continues to shadow her days.

“As a younger person, I would have responded more spontaneously and fearlessly, but now, the thought of repercussions often makes me go silent. There is an impotent rage that both depresses me and makes me more anxious,” she said.

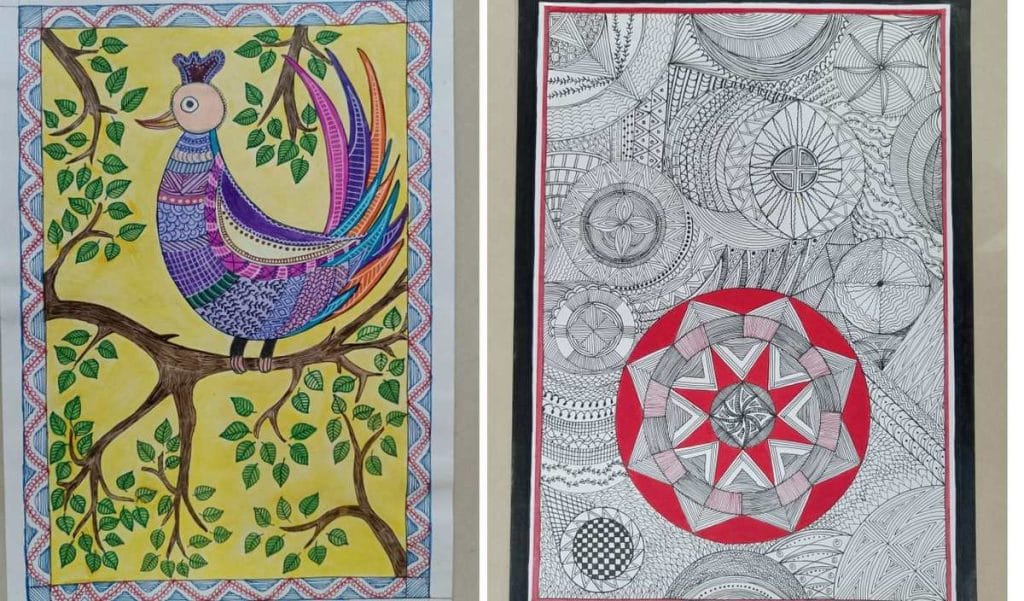

Since retiring from a busy media and academic career, she has returned to a refuge that predates therapy: art. Rather than talking through feelings, it allows her to channel them.

“I used to draw and paint a lot when I was young. There was a complete full stop when I got married at 21. Music, drawing, and dance, always were and are very close to my heart,” she said. “During Covid, my daughter-in-law gifted me an adult colouring book. I started colouring, but my mind was restive. Why don’t I create my own designs? There were ideas coming out of my ears.”

At 64, she took an ‘Art for Self Therapy’ course on Udemy. She now sketches regularly and calls it one of her most therapeutic outlets. Through her organisation Ayeka, which designs educational modules on various subjects—from art to personality development—she also promotes awareness about mental health.

Art has helped KPG too. Like Sadasivan, he has turned to painting as a form of healing. But for him, it’s his military-style schedule that holds everything together. He painstakingly notes it all down in his diary—it helps him remember to live well.

Many older adults bottle up the emotions and thoughts that gnaw at them—feeling invisible, depressed, anxious, or terrified of dying alone. These feelings often show up in other ways, including physical symptoms.

A tight schedule

KPG wakes up at 4 am every day, without an alarm. This, he says, is brahm yog—the sacred hour when gods walk the earth. By 4:30, his green tea is ready. By 5, he’s on his balcony doing yoga, followed by a walk and breakfast. By 9, he has showered, pulled on a crisp safari suit, and settled into his sofa. Now the real test of the day begins– killing time.

At 88, KPG has been left all alone since his wife Meena died after a protracted battle with Parkinson’s disease. He is in regular contact with his two children, one in the US and the other in Noida, but the days stretch long. His friends in the colony have all died, one by one. On his society group, there are regular messages of citizens wishing ‘Om Shanti’ to departed souls. He has kept these groups on mute.

“I don’t have friends in the society or at the temple, all the people who walk in the morning are way younger to me, so I have nothing to do,” he said in his apartment, flipping through news channels on his television.

KPG is originally from Jhumri Telaiya, a small town in Jharkhand. He made Delhi his home in 1989, when he was allotted the Vasant Vihar house through a lottery. He retired there in 1995.

I have made friends on the (Emoha) app. One member calls me her elder brother, while the other refers to me as Tauji. I love being on the app

-KPG, 88

Much of his life since then was spent caring for Meena, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 1996. He would care for her all day, attend conferences on the disease, and reach out to doctors conducting research on new treatments that might help.

“I wear the sweaters my wife knit even today,” he said, his face softening up with memories of Meena. “She loved arts and crafts and used to meticulously note down her recipes in notebooks… she was just a lovely person.”

They were married for 56 years. After she died, there was a void in his heart and life. Suddenly, there were no doctors to chase, no conferences to attend, and no new experimental drugs to try. He was overcome by loneliness and ended up falling extremely ill. He went to the United States in 2019 to seek treatment and therapy and live with his son. But when he returned to India, he had a massive stroke. A ventricle of his heart was replaced.

That, he says, was his wake-up call. He had to find new purpose.

When older adults start withdrawing from life, the decline can be quick and severe, according to psychiatrist Bhalke.

“In older patients one can sometimes see apathy, a loss of interest in doing activities, hobbies, or talking to people. In extreme cases, this can even lead to psychosis—they get hallucinations, start muttering to themselves,” Bhalke said.

The turning point for KPG came when someone told him about the Emoha app. He decided to give it a try and it’s now his window to the world.

After finishing his elaborate morning routine and getting dressed, KPG logs into the Emoha app. He attends cooking classes, birthday celebrations, singing and dance sessions.

“I used to be a singer, but had completely stopped singing in the later years of my life. Now I have a harmonium and a keyboard and I practice on it, and sing at Emoha events,” he said.

He records the sessions on his phone and often replays them later. His phone is full of videos, friends, and affectionate voice notes.

“I have made friends on the app. One member calls me her elder brother, while the other refers to me as Tauji. I love being on the app,” he said.

On some weekends, his daughter and her family visit him in Vasant Vihar.

“She is busy building her company but often comes here to visit me,” he said.

Satsangs and SOS calls

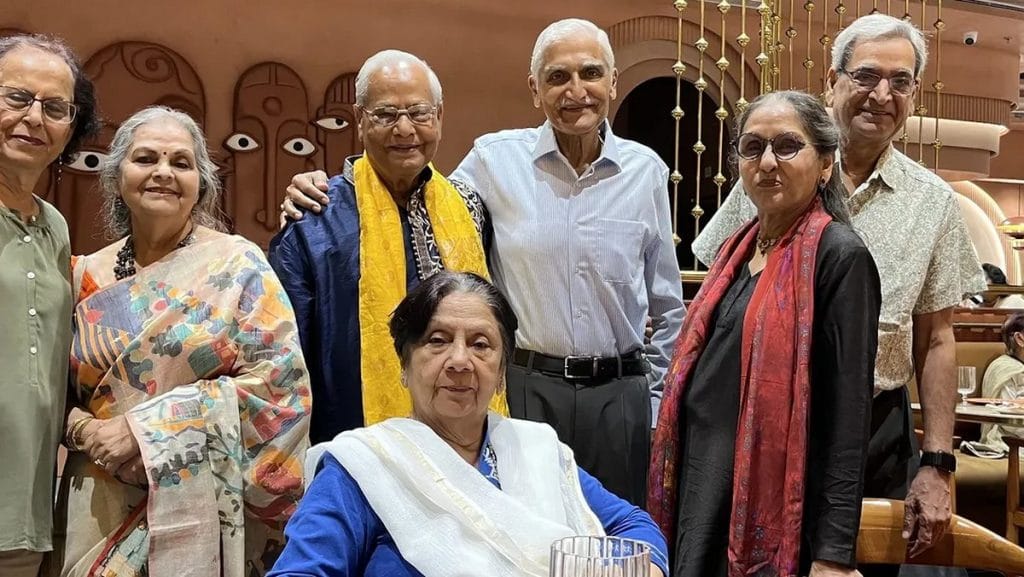

Even as KPG finds companionship through a virtual platform, others fight loneliness through neighbourhood meet-ups, satsangs, and old-school camaraderie.

The Senior Citizens Council of Delhi was founded in 2006 by JR Gupta, a retired government officer, as a platform to address both elder abuse and isolation. What started as morning walks and laughter sessions at Deer Park has now grown into a recreation centre in Green Park Extension as well as a sprawling network with 18 lakh members across India.

It’s part of the network of HelpAge India, which conducts group counselling sessions and workshops daily across the country. Such senior citizen associations have also become important intervention points for seniors to get support and seek help.

“HelpAge India has partnered with more than 1,500 senior citizen associations, whose members are given a forum to come and express in three-four-hour-long workshops the trials and travails they’re subjected to either through community or their families,” said Prateep Chakraborty, COO of HelpAge India.

But the Green Park centre now has a decidedly religious vibe, with elders congregating to listen to Ram katha, Sunderkaand paath, Bhagavad Gita verses, and other religious texts. In a separate room, free physiotherapy is offered.

For many, religion is a form of meditation. Seventy-year-old Neelam Malhi, a retired agriculture department worker and economics graduate, is one of them. Since her husband’s death in 2016, satsangs have given her a sense of contentment. Most of her days are spent attending one religious sermon or another. Gurbani plays constantly on her television.

“Religion is our (older people’s) sector, you know,” she laughed. “Attending these sermons and then talking to relatives on the phone at night… I don’t even realise when my day ends!”

A resident of Green Park, she’d come to the community centre on a Wednesday to participate in the Sunderkand paath, where close to 50 elders sang bhajans together.

The Senior Citizens Council also runs a helpline for elderly people facing abuse. Gupta says they regularly receive distress calls.

“They come to us crying, facing abuse at the hands of their own sons and daughters-in-law. Some people face verbal abuse, humiliation, in some cases they are deprived of food and are shut in the house,” Gupta said. “We give them a sense of community here, as well as provide free personal and group counselling.”

Another of the council’s priorities is promoting digital literacy among the elderly to help them counter loneliness. According to Gupta, isolation can exacerbate mental health issues and also increase vulnerability to abuse at home.

“The elderly don’t know how to use mobiles, and that can lead to social isolation in today’s day and age. We conduct digital literacy programs frequently so they learn how to access government welfare schemes and stay connected to their relatives through social media,” he said.

Also Read: India’s silver economy is booming—app, startups, part-time ‘daughters’, dementia centres

Duty and succour

As parents age, so do their caregivers. Rachna Lamba, who lives with her 95-year-old father in South Delhi, turns 60 this month, officially a senior citizen herself.

In 2015, she left her full-time job to care for her father, Kuldeep Singh. They enjoyed many trips together—Ladakh, Thailand, Goa, Kerala—until Singh fell gravely ill last August.

Now, her days revolves around him. On some nights, she barely sleeps. She had plans to launch a website but put them on hold to tend to her father.

In the evening, Kuldeep walks slowly out of his bedroom, sits with a spittoon and a cup of tea, and carefully dips a Marie biscuit until it melts. Lamba is by his side all the time, crushing biscuits for him, and keeping up a conversation. Though Singh smiles back, he’s been increasingly disoriented about space and time.

Lamba has the support of family and friends, but being the primary caregiver can be overwhelming.

“Just the financial burden of it all. When he was hospitalised and I couldn’t immediately break the fixed deposits, I had to lean on my friends to help me out,” she said.

Still, she is not paralysed by loneliness. Even if there have been anxiety-inducing moments, yoga, meditation, reiki, and spirituality keep her centred.

Back in Vasant Vihar, KPG logs in to a cooking class on Emoha. The host greets him, as do the other participants, and his eyes grow misty as warm words of welcome come his way.

“As long as I have these people by my side, I will be fine,” he said.

This article is part of Grey World, a series on India’s senior communities. Read all articles here.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)