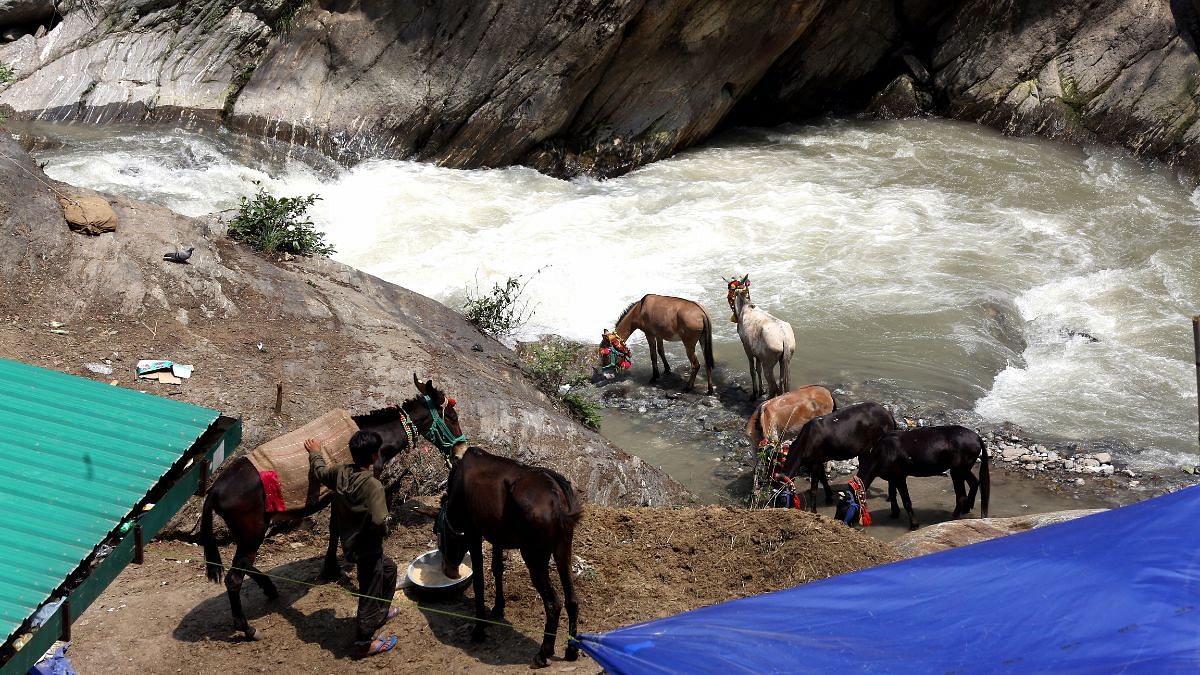

Kedarnath: Hundreds of devotees jostle around the entrance gate in Kedarnath as a limping mule, with his saddle still fastened, is dragged by his owner on a muddy path away from the main road. With blood dripping down his front leg, the mule is brought to a dispensary—two km from the Gaurikund gate—to get his wound checked by the government-mandated veterinarian.

The extent of mule injuries and deaths during the pilgrimage season is an unacknowledged tragedy that gets subsumed in pilgrim welfare. Orders from the Uttarakhand High Court and National Green Tribunal on the supervision of the mule business are, for the most part, ignored. And animal rights advocates are calling for more shelters, stricter regulations and crowd management.

It has barely been a month since the Char Dham Yatra began, and veterinarian Dr Shiv Kumar Tiwari is used to seeing 20-30 sick and injured mules a day at his dispensary. The number will only increase to 60-70 a day as the Yatra picks up, he said.

Two veterinarians and a pair of para-vets tend to the injured mule in the small shed at the edge of the muddy road. They clean the wound with betadine, administer a painkiller, and ask the owner how it got the injury, despite knowing the reason already—apathy, over-exertion, lack of infrastructure.

The government does not have a single hospital to tend to mules injured during the yatra. The onus falls on Tiwari’s clinic, and three other out-patient dispensaries (OPDs) with one vet each on the 18-km long trek route—the longest among the four Char Dham Yatra routes.

With such poor facilities, the roughly 10,000 mules that ferry pilgrims and goods up the precarious mountain route in Kedarnath are pushed to their limit. Multiple leg and back wounds are common. Many die, with little to no repercussions for their owners.

“People come here for a spiritual pilgrimage but want the comfort of sitting on an animal and going to the temple. Is that right? Is it humane?” asked Dr. Ashish Rawat, the Chief Veterinary Officer of Rudraprayag district, which Kedarnath falls under.

The state machinery is geared toward prioritising the teeming masses of devotees during the Char Dham yatra, while the thriving mule industry flounders without oversight. Only in 2023, after a Uttarakhand High Court order, did the district administration of Rudraprayag build the first and only shelter for injured equines and victims of cruelty.

“Unregistered or abandoned mules make it difficult to track down the owner to make him accept responsibility. There are barely enough facilities on the yatra track to deal with grievously injured animals. And authorities are so overwhelmed by human pilgrims that stranded animals get neglected,” said Shashikant Purohit, director, working animals project, Kedarnath with People for Animals, Uttarakhand (PFA). He runs the shelter in Rudraprayag.

People come here for a spiritual pilgrimage but want the comfort of sitting on an animal and going to the temple. Is that right? Is it humane

Dr. Ashish Rawat, Chief Veterinary Officer of Rudraprayag district

Also read: Animal cruelty needs more than tough laws, aggressive policing. Colonial-era battles show why

First-ever mule rescue in Kedarnath

Parvati was the first ever mule rescued in the history of Kedarnath.

“How do I know she was the first? Because the authorities were completely unprepared for it,” said Purohit. That was barely a year ago in June 2023.

“I was lucky enough to be there and notice her when I did, but there must have been hundreds like Parvati before who weren’t rescued in time and lost their lives due to their injuries,” he said.

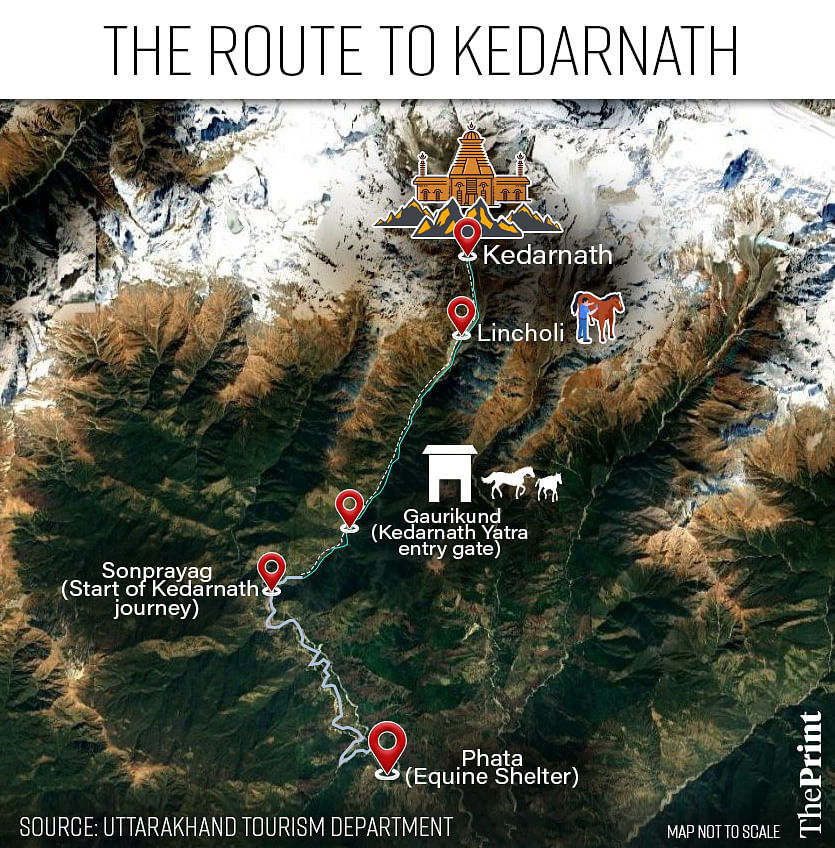

He was walking on the narrow, slippery path of the Kedarnath route near Lincholi village, when he saw a badly injured female mule lying by the side of the road. She was limping on one leg. It was a fracture, but there was no sign of her owner or anyone to claim her. Her right ear was pierced, he knew she was a registered mule, but the yellow registration tag was missing—probably removed by her erstwhile owner so she couldn’t be traced back to him, a common practice until last year.

Purohit and his colleagues from PFA named her Parvati and started tending to her injury. Every day, they would climb the eight or so km of the route to her spot with supplies from the base camp.

“We gave her first aid and basic treatment with the help of a government veterinarian from the trek route, but we obviously couldn’t leave her there. We needed to bring her back down from the mountain,” said Purohit.

After over two weeks of visiting her daily, and requesting all the authorities from the animal husbandry department to the NDRF to the district administration for assistance, they were at a dead end. There was no animal ambulance in Kedarnath, and no vehicle could come that far up the trek route.

It was a sanitation organisation, Sulabh International, that finally came forward and offered PFA one of their garbage trolleys. Parvati was wheeled down the mountain on the trolley. She was sent to the PFA sanctuary in Dehradun for further treatment.

“Parvati’s case reveals everything that is wrong with the current management system of mules here,” said Purohit.

In 2023, as many as 19 lakh people visited Kedarnath. This year, four lakh people have made the trip just in the first month of the Char Dham Yatra. But the 8,000 registered mules that carry these pilgrims have only seven veterinary officers, five sheds to rest along the way, and one equine shelter in Phata, Rudraprayag.

There are barely enough facilities on the yatra track to deal with grievously injured animals. And authorities are so overwhelmed by human pilgrims that stranded animals get neglected

– Shashikant Purohit, director, working animals project, Kedarnath with People for Animals, Uttarakhand (PFA)

The lone shelter, some 22 km from the Gaurikund gate, was built in June 2023 by the district administration, which runs it with the PFA. At present, there are 12 mules in its infirmary. It’s open to all equines that have been seized from their owners under the Prevention of Cruelty To Animals Act.

“It is currently the only place I’m aware of where we can keep ill-treated mules over the long term and ensure their safety,” said Purohit, who runs it along with four workers including one vet.

“But it can barely house 35 or 40 mules, and there are 100 times as many mules on the trek right now. This is a start, but there’s a long way to go for the district and state governments to ensure adequate infrastructure for the mules of Kedarnath,” he added.

Also read: A Mumbai police officer is dog’s best friend. He files FIRs against cruelty

‘Carrying capacity’ of Kedarnath

At a small dhaba in Sonprayag—the village from where all pilgrims begin their journey towards Kedarnath either by helicopter, mules, palanquins or by foot—recently returned devotees discuss their arduous trek. They gripe about the heat, they’re worried about overcrowding and are resigned to the narrow roads. And then there are the mule accidents in the 8-hour-long trek.

Dhirendra Kumar, a 59-year-old pilgrim from Sambalpur, Odisha who completed the trek on 24 May recounted how he saw a mule crashing into a female pilgrim and injuring her.

News articles in Samvad also mention how a mule on the Kedarnath Yatra trek suddenly jumped up and kicked a pilgrim in his stomach. The National Disaster Relief Force had to rescue the unconscious man on a stretcher.

“The Kedarnath route is just too ecologically fragile for the number of mules and pilgrims. The problem lies in the carrying capacity—if you don’t enforce it, you’re just waiting for a stampede to happen,” said Gauri Maulekhi, a PFA trustee and a member of the Society for Prevention of Cruelty against Animals (SPCA) in Rudraprayag district.

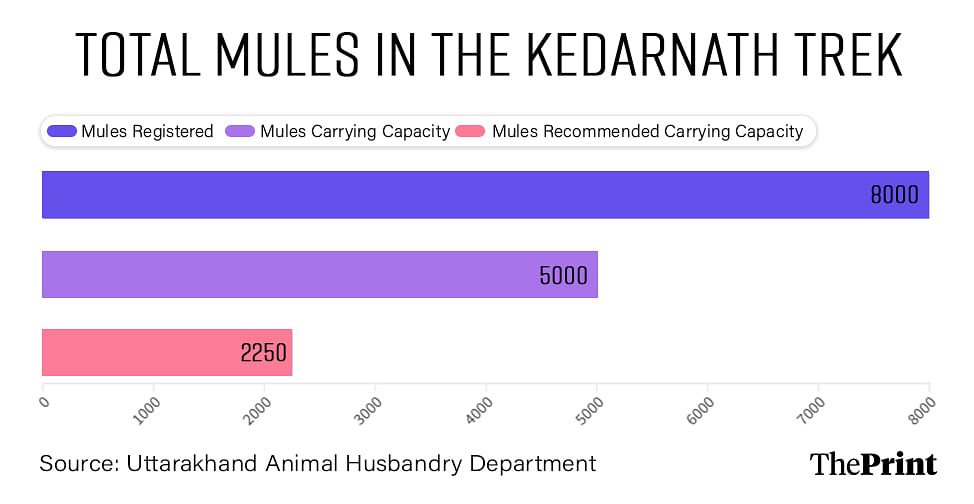

Carrying capacity is, as the name suggests, the official human/animal capacity a particular region can sustain without damage to its ecology. There are multiple debates on the official carrying capacity of mules in Kedarnath, with different studies conducted by authorities at different times.

A Joint Committee Report drafted by the Uttarakhand State Pollution Control Board, MoEFCC, and GB Pant Institute and submitted to the National Green Tribunal in 2022 fixed the Kedarnath carrying capacity at 2,250 equines. This takes into account the length and width of the track and the average size of mules. The Animal Welfare Board of Uttarakhand on the other hand has recommended a capacity of 3,800 mules in its studies, the latest of which was in 2022.

The Kedarnath route is just too ecologically fragile for the number of mules and pilgrims…you’re just waiting for a stampede to happen

– Gauri Maulekhi, PFA trustee and SPCA member

Now, the official capacity has been set at 5,000 mules by the Animal Husbandry Department of Uttarakhand, but there are over 8,000 registered mules this year.

“There’s an unprecedented number of pilgrims this year, so we have registered more mules to allow them to work in shifts—4,000 one day, and 4,000 the next. This is so that mules can also get some rest,” said Dr. Neeraj Singhal, the Director of the Animal Husbandry Department.

But the numbers are deceiving. Conservative estimates from residents including mule owners and veterinarians on the trek route peg the actual number of mules at 12,000-15,000. Despite a three-step verification process—a registration tag on the mule, a license of the owner, and a microchip inserted into the pack animal—unregistered and unaccounted mules are easily able to slip under the authorities’ radar.

“There are some mules that are parked by their owners along the yatra trek, and never brought down to the main Gaurikund gate so they evade the registration point,” said Purohit.

Some mules only ferry passengers between two checkpoints on the trek, while others may have a registration that belongs to a different or dead mule.

“Some are just really good at sneaking past the guards. When there are 5,000 plus mules every day, even the authorities are unable to keep track after a point,” he added.

Unregistered, unaccounted animals

The smell of rot overpowers the beauty of the route between Sonprayag and Gaurikund villages, going toward the Kedarnath gate. Villagers are used to the vile stench. They call it the ‘mule-dumping spot’. It’s where owners dump the bodies of the pack animals that failed to make it into the river below, their carcasses left to rot.

An unregistered mule doesn’t just create problems of miscalculation for the authorities, it allows owners to run their business without oversight. This could mean charging pilgrims exorbitant rates, not following mandatory health check-up protocols for the animals, providing them with adequate food or rest, or even a proper burial.

According to government data, 200 mules died in Kedarnath in 2022, and 115 died in 2023. Twenty animals have already died in the first 20 days of 2024. But these are only the official, registered deaths. Villagers, pilgrims, animal activists, and mule owners—all admit to seeing mules collapse or slip on the treacherous path and their owners either leaving their bodies on the roadside or pushing them off the cliff.

Insurance has emerged as a bone of contention between those advocating for the animals and their owners. The Uttarakhand government made it mandatory in 2022, after the Covid-19 pandemic, to have an insurance policy for all mules that are registered for the Char Dham Yatra.

“Now, we make it a point to insure all mules, and the government provides 60-80 per cent subsidy on the insurance,” said Dr Singhal.

While the intention may be good, animal rights organisations like PFA say that such mandatory policies incentivise cruelty.

“If a mule is grievously injured, the owner would rather let it die than spend the resources to heal it. If it dies, the owner gets insurance money from the government,” Maulekhi alleged.

Other yatras like the one to Vaishno Devi in Jammu, where 3,200 mules operate, also have free dispensaries and treatment for mules but have no such insurance policy. Vishesh Mahajan, one of the members of the SPCA in Vaishno Devi, pointed out that their track is much shorter and safer than that of Kedarnath. Mule fatalities are not so frequent here.

If a mule is grievously injured, the owner would rather let it die than spend the resources to heal it. If it dies, the owner gets insurance money from the government

– Gauri Maulekhi, PFA trustee and SPCA member

The Uttarakhand animal husbandry department on the other hand justifies the insurance policy as a fair scheme to compensate mule owners who earn a majority of their income during the six-month period of the yatra. The district administration has also made medical treatment free for mules, with all dispensaries only requiring a Rs 10 levy for any injury treated.

“The going rate for a mule is between Rs 1-2 lakh, so it is a huge loss for them if a mule dies by accident,” said Singhhal.

Also read: Rise of veganism has been hard in vegetarian-friendly India. Milk is the final frontier

How is cruelty dealt with in Kedarnath?

The wounds that Char Dham mules come with to the PFA sanctuary in Dehradun are not ‘day-old’ wounds but run deep enough to need at least six months of constant treatment.

“One thing I can say is—it is never accidental. The owner is never unaware that the animal is hurt or malnourished, in fact, he just chooses to ignore the pain the animal is in,” said Binu Bhadauria, a former employee at the Animal Husbandry department of Uttarakhand, who is now a veterinarian with PFA.

Cruelty is defined by the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1960 as physically hurting an animal, making it work in an unfit condition, administering an injurious drug, or not providing it sufficient food and drink, among other things.

In 2023, the animal husbandry department of Uttarakhand said there were 3,482 medical treatments administered to mules on the Kedarnath route, while 215 challans (fines) were imposed on owners for breaking mule caretaking rules. Additionally, 17 FIRs were lodged under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act.

Most of these owners are profit-motivated, and try to work the mule as much as possible. I wouldn’t say they’re inherently cruel, because they also think it is just two or three crucial months of work and then they let the mule rest

– Dr Ashish Rawat, CVO of Rudraprayag district

Here, too, the numbers downplay the magnitude of injuries. Before the construction of the equine shelter in August 2023, the police had no place to keep the animals seized under the PCA Act. So while they would lodge a complaint under the Act, the animal would more often than not be returned to the owner while the case was going on. An important thing to note here is also that according to the IPC, a fine for cruelty against animals is merely Rs 50, which is in no way a deterrent.

“An example can be made and cruelty can be prevented only if you keep the victim away from the perpetrator” Purohit said. “Imposition of a fine is nothing but a rap on the fingers of the mule owners. Who is to say they won’t repeat this behaviour?”

What is the solution?

Over the last year, 12 mules from the yatra, whose owners have been accused of cruelty, have landed up at the lone shelter at varying stages of injury. Most mules have deep wounds on their backs called saddle sores, or cuts and scrapes on their legs, as well as signs of exhaustion and malnourishment.

Saddle sores occur when the rough wooden saddle is badly adjusted and constantly rubs against the animal’s back whenever a passenger is riding on it. It is a common wound among Yatra mules, said veterinarians, and often goes unnoticed because owners hardly ever remove the saddles.

Purohit and his coworkers at PFA have sometimes discovered injured mules on the Kedarnath trek when they saw blood dripping down their sides. They immediately intervene, and force the owner to remove the saddle to find deep wounds underneath.

Government veterinarians like Dr Tiwari, and the Chief Veterinary Officer (CVO) of Rudraprayag district too agree with Shashikant and Dr Bhadauria’s assessment of mule owners in Kedarnath.

“Most of these owners are profit-motivated, and try to work the mule as much as possible. I wouldn’t say they’re inherently cruel, because they also think it is just two or three crucial months of work and then they let the mule rest,” said Dr Ashish Rawat, CVO of Rudraprayag district where Kedarnath falls. For any change in the management of mules at Kedarnath, the authorities have to first change the behaviour of mule owners—and the pilgrims.

It’s common for pilgrims to hinder the authorities from doing their job and checking in on the well-being of the animals at regular checkpoints, since they are more concerned with finishing their pilgrimage.

Still, the Kedarnath trek is a trailblazer of sorts among the Char Dham treks of Uttarakhand. Yamunotri, Gangotri and Badrinath are yet to have a fixed carrying capacity of mules, or an equine shelter to house injured mules. According to Dr Singhal, survey work is still underway on the other routes. Kedarnath is the longest trek with arguably the most number of mules and was selected as a starting point.

There are still little wins for the Kedarnath rescued mules at the shelter—they’re becoming healthier and fatter.

“Most of these mules that come here exhibit hand shyness—they’re scared of human touch,” said Purohit, opening the latch to one of the enclosures to let animals out for the day. “It could be because of the abuse they’ve faced by their owners.”

Now, after almost a year at the shelter, the mules canter out. and a few stop to nuzzle Shashikant’s outstretched arms. They are no longer afraid.

The veterinarian was incorrectly identified in an earlier version of this article. It has been corrected.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

had cows been used, then there would’ve been so many gau shalas there….. only respect for cows and not even a human being!! donno what for are the local authorities and animal husbandry depts….??