Srinagar/Shopian: “Allah has given him a very sharp brain. He has always been a topper…He would go for his classes to study even during bandhs,” says Rafiq Ahmed about his son Inamul Haq, a 2012-batch Indian Police Service (IPS) officer from Shopian district in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).

Haq, a junior of IAS officer Shah Faesal, the first Kashmiri to top the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) exam in 2009, had followed in his footsteps. Like Faesal, the 38-year-old was a doctor before he appeared for the civil services.

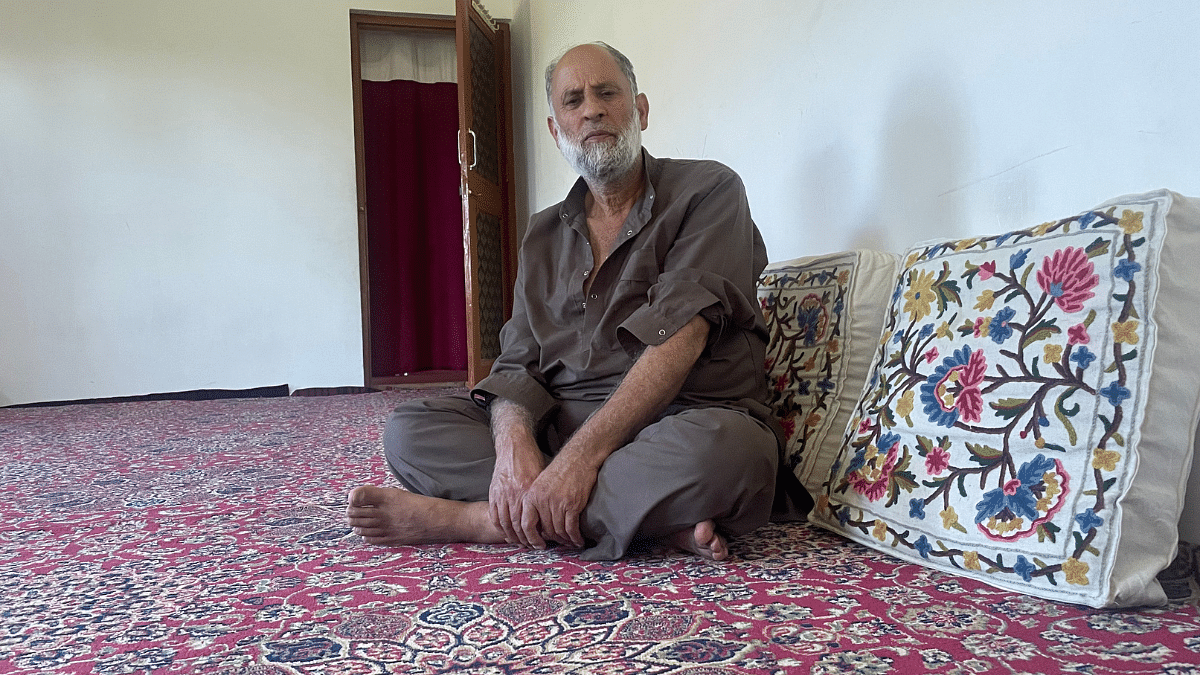

“He (Haq) had topped the MBBS exam in J&K, too,” Ahmed says in a tone of restrained pride, as he sits cross-legged on a traditional pink woollen carpet in the large, empty drawing room of his two-storey home in the quiet village of Draggad in Zainpora. “But then, Shah Faesal encouraged him to take the UPSC exam, and he cleared it in one go.”

The retired accounts officer is less forthcoming to questions about his younger son, Shamsul Haq. He was killed in an encounter in January 2019 just a few kilometres away from their home. Like his brother, Shamsul had been pursuing a degree in medicine.

A few months before the encounter, Shamsul had joined the militancy. “What can I say? Will any parent want his son to pick up the gun?” Ahmed says. “Picking up the gun means an invitation to death. Why would I want that?”

In J&K Police circles, the story of Inamul and Shamsul is held as a cornerstone of the situation—a grim and stark reminder of the porousness of the borders between policing and militancy, law and crime, good and bad in their homeland.

Similar grim tales of dilemmas, guilt, ostracisation, and a perennial fear of death abound in the J&K Police ranks, right from officers down to the constables.

“In Kashmir, police and militancy exist within the same classroom, the same family, sometimes within the same person,” says a retired IPS officer. “It is not easy being the police here…Inamul could not convince his own brother to give up arms. How do you convince your people to?” he asks, rhetorically. “Through force.”

Since the late 1980s, the J&K Police has been actively used as a counter-insurgency force. For Kashmiris as well as militants, the police are the most visible, intimate face of what they see as “state repression”.

As a force taking on militancy, the police’s biggest advantage is that they are locals. They speak the same language, come from the same villages, have the same social circles as not just ordinary Kashmiris, but also the militants. Their information network remains unmatched in comparison to the Army, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), or the Border Security Force (BSF).

But that’s what makes them the bête noire of Kashmiris—the sentiment of ‘how can they turn against us’? Unlike the Army and the CRPF, after work in the evening, a policeman has to return home amid the azadi-sympathisers or militants, who they fight through the day with pellet-guns, tear gas shells, and AK-47s.

As some policemen privately concede that their lives oscillate between anger, guilt, and the call of duty.

Also Read: With Kashmir in election mode, security bureaucracy unprepared for looming mountain war with Jaish

The first attack

Kashmir has been a police state since 1947, says political scientist Noor Ahmad Baba. “Even before that, on 13 July 1931, the Maharaja’s forces had killed 21 Muslim protesters agitating against his regime,” he says.

Former chief minister Sheikh Abdullah described the firing as the ‘Jallianwala Bagh massacre of Kashmir’. It was observed as the Kashmir Martyr’s Day until December 2019, when the Union Territory administration dropped the day from the list of gazetted holidays.

“In that sense, the police have always been highly politicised,” Baba says.

J&K further turned into a “surveillance state” after Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad took over as then prime minister in 1953 after a midnight coup against Sheikh Abdullah, the octogenarian academic says.

“Growing up, I remember the police would open fire on minor provocations. It was normal for us…It was only in 1976 when I came to JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University), and saw the police quietly observe students’ protests without taking any action, that it hit me that we were living in a police state.”

With the release of Abdullah in 1975 and the signing of the Indira-Sheikh Accord, Baba says, there was a semblance of civil liberties in the Valley followed by an over 10-year spell of peace—one that was irrevocably interrupted in 1987.

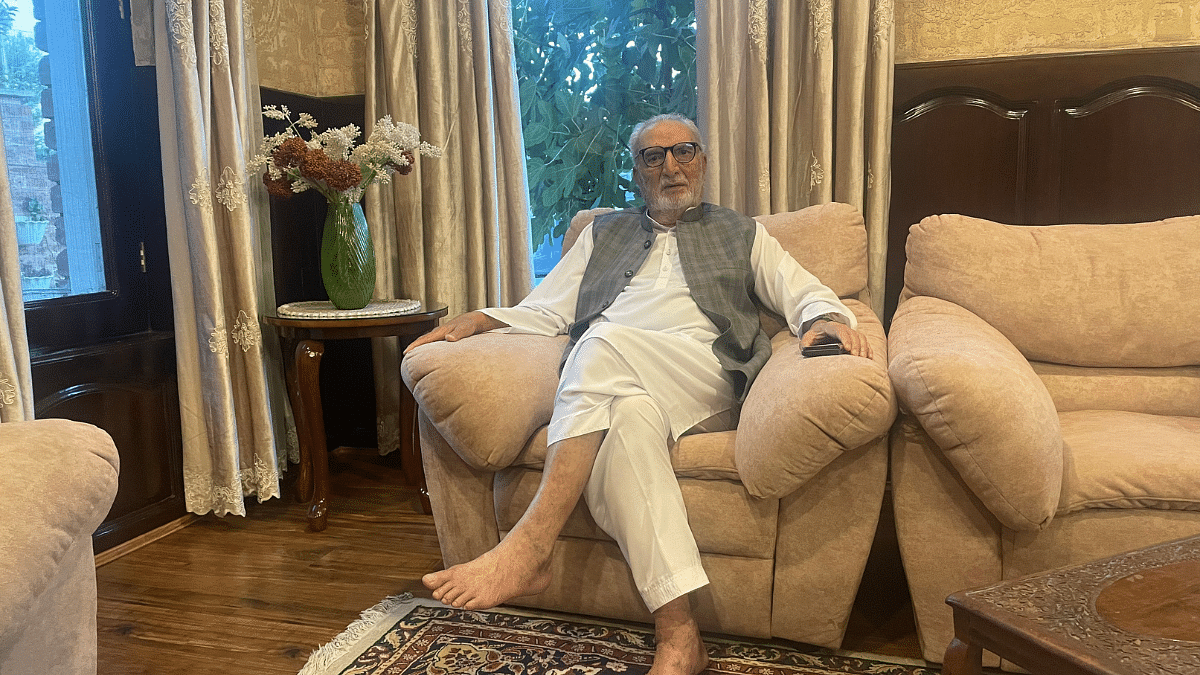

Until the late 1980s, the job of a policeman in Kashmir was like any other in the country, recalls A.M. Watali, a 1956 batch officer from the Kashmir Police Service (KPS), who was later promoted to the IPS. “It was to fight crime, and here in Kashmir, crime was also less than in other parts of India,” he says as he sits in his palatial home in Srinagar in a crisp white kurta and grey Nehru jacket.

Watali retired in 1989, the year in which militancy in Kashmir began. “The first information about armed militancy came from the police,” Watali, who was posted as Deputy Inspector General (DIG) in the Kashmir Valley, recalls. “We got the information of infiltration…That local boys were going across the border and coming back with arms.”

The first militant attack was, in fact, on his house, Watali, whose tell-all memoir ‘Guns Under My Chinar’ chronicles the early years of militancy in Kashmir, says.

“I was living in Raj Bagh at the time when three men came to my house. One of them wrapped up in a shawl told the constable outside that he wants to meet me,” he says with his eyes popping out through his large, black-framed glasses. “When the constable said he cannot come right now, the guy pulled out a massive gun, and a scuffle ensued…His two comrades who stood outside began shooting, and a bullet hit him (the militant), and he died.”

When Watali came out, the militant had already been rushed to the hospital. But he had left behind him the “massive gun”, which turned out to be an AK-47 that made its way from the recently-concluded Soviet-Afghan war. In no time, the Valley was flooded with the flashy new weapon. Until then, as Watali says, nobody had seen it in Kashmir. “We, in the police, just had your .303 rifles.”

As investigations unfolded, the police found out the militant was Aijaz Dar, a Kashmiri who would move around as an aide to Mohammed Yusuf Shah aka Syed Salahuddin until the 1987 assembly elections. A policeman remembered playing cricket with Dar, a neighbour, while growing up.

Salahuddin had, like many other to-be-armed militants, contested in 1987. After losing to Ghulam Mohiuddin Shah of the National Conference, in what is widely believed to be a completely rigged election, he crossed the Line of Control, and began to head the Hizbul Mujahideen.

“So, in a way the first target of the militants was us, the police,” Watali says. “But we—the police alone—ran a very successful operation thereafter, and caught 72 boys across the Valley along with their weapons. It all remained under control,” he claims. “Till that time, everything was peaceful. Tourists kept coming, Pandits were safe and calm. Things were in control.”

Another serving KPS officer agrees. “In 1989, there were 133 militants in the Valley, and the police knew each and every one of them by name,” the officer said. “Every intelligence input, every operation was carried out by the police.”

However, the Centre insisted that the Kashmir police deploy the CRPF for counter-insurgency, Watali says. “I was told by the chief secretary that the Home Minister thinks that I should deploy the CRPF… My response was ‘they will be very vulnerable. If they get attacked, unlike the police, they would not know where to go, where to get information from…They don’t know Kashmir like the police’.”

Even now, 35 years later, Watali speaks with a sense of urgency, “The police speak the same language, know the beliefs and the culture of the people. They needed to spearhead the counter-insurgency.”

However, what appeared to be just a suggestion from the chief secretary soon became an order from then chief minister Farooq Abdullah, says Watali. “The CRPF was deployed; the army took control; the police took the backseat. I knew the situation was going to escalate.”

From community police to counter-insurgency force

By the early 1990s, the J&K Police had become a passive aide to the army and the central forces. As police officers, serving and retired, recall, nobody took the police seriously—neither the militants, nor the central forces. The police, as an officer says, was the quintessential paper tiger.

“There was at least some degree of suspicion that the police may be sympathetic to the azadi cause, and that they could not be trusted,” Watali recalls. “There were some cases where police personnel also resigned and joined the militants, but those were not very large at all.”

The perception that the police were sympathetic to the cause of ‘freedom’ was not unfounded, a Kashmiri social worker says. “Until the 1990s, they were very good…they were part of the society. It was a time when you could support the cause of azadi in your heart, and still serve in the police.”

In 1993, things came to a head as constable Reyaz Ahmed Ganaie, a resident of Bandipora district, was allegedly shot dead by Army personnel at Hazratbal Dargah. Hundreds of police personnel descended on the streets of Srinagar brandishing service weapons to protest against the killing of their colleague. According to some accounts, the police staged anti-army protests for over a week, which the army had to eventually quell through a joint operation with the CRPF.

“That was the last time the Jammu and Kashmir Police protested,” says Afhadul Mujtaba, a retired IPS officer. “After that, the character of the police itself underwent a foundational change.”

In 1994, a counter-insurgency wing was established to involve “the passive J&K Police in the anti-terrorist activities and giving a local face to these operations.” The Special Task Force (STF), now known as Special Operation Group (SOG), comprising a 1,000-strong volunteer force with officers and policemen from ethnic groups Kashmiris, Gujjars, Dogras, and Sikhs, was thus formed. Some of these men had been victims of militancy themselves.

“When the STF was formed, most of the people brought to it were from Jammu. They were Muslims from Doda, Punj, Rajouri, but their homes were not in the Valley,” another retired police officer says. “They were technically part of the J&K Police, but they had the distance and anonymity of the Army. They did some very good operations, but their connect with the public broke.”

As Kashmiri journalist Basharat Peer wrote in 2002, the STF became synonymous with two things—killing militants, and alleged human rights violations.

The killings had strong incentives. As former police officers said, every militant killed earned the STF anywhere between Rs 35,000 and Rs 50,000. Capturing militants with arms and ammunition came with an extra bounty. There were also quick, out-of-turn promotions. As a media report stated, hundreds of officers rose up the ranks, while hundreds of policemen have become officers in a matter of a few years, thanks to their stints in the STF.

“Since the job of the STF was both unpopular and risky, it was felt that there had to be tolerance for the bad things they did, at least initially,” the serving KPS officer mentioned above says.

By the late 1990s, the “volunteer” aspect of the STF disappeared. “It became like any other posting, if we were asked to go, we had to go.”

Such was its unpopularity that in 2002, Mehbooba Mufti promised to disband the STF if the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) came to power. “The SOG has committed untold atrocities on the people. To disband SOG would be our first task after assuming office,” she said.

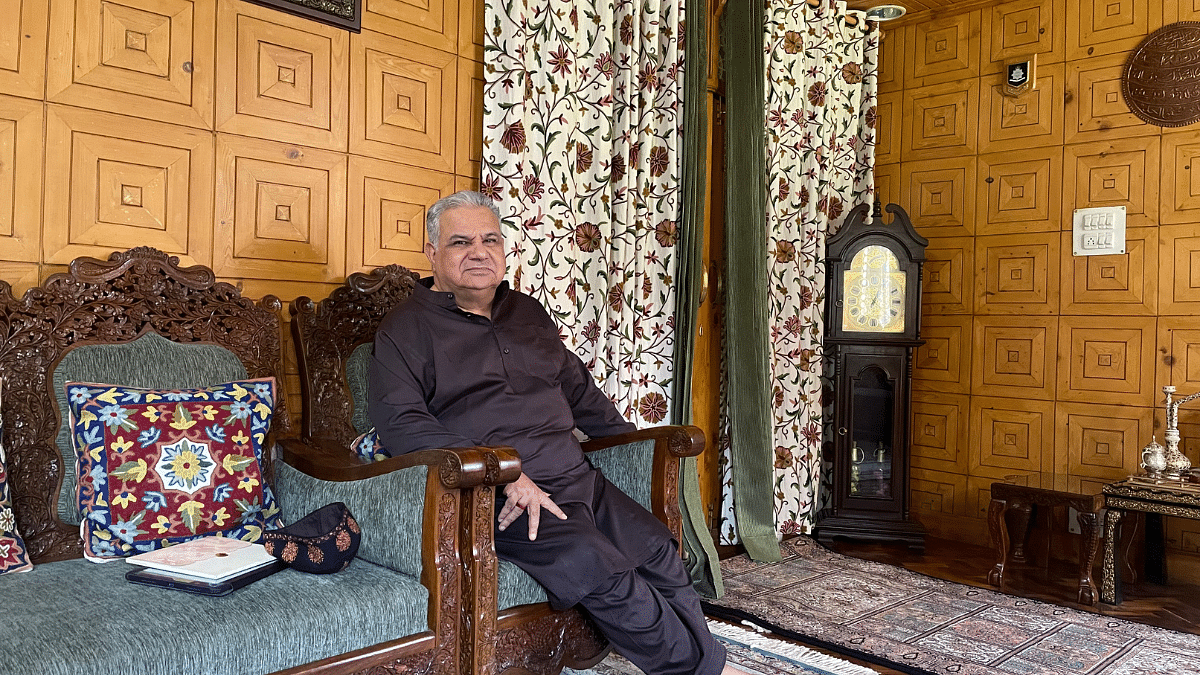

“The task of the police anywhere in the world is to interact with people, and ensure law and order,” says Mujtaba, a 1984-batch KPS officer, who later promoted to the IPS. Until the revocation of Article 370 in 2019, J&K had the provision of promoting 50 percent officers from the Kashmir Administrative Service, the Kashmir Forest Service and the KPS to the IAS, IFS and IPS, respectively. Since 2019, this figure has been slashed to 33 percent like in the rest of the country.

“You have to ask what the police are for?” Mujtaba, who just retired from the State Service Commission as a member last year, says.

A tall, pathan-style kurta-pyjama-clad constable patrols his home. Like many other retired Kashmiri police officers, Mujtaba has been given security even after retirement. “The main role of the police is not to deal with insurgency,” he says.

“The orientation of the Army and the police are completely different…The job of the army is to protect the geography, the job of the police is to protect the people,” he says. “When the two get mixed, as they have here in Kashmir, things get difficult.”

Through decades of working closely with each other, the police and the army, Mujtaba says, have adopted each other’s traits. “The police have become more army-like here, even as the army has picked up traits of the police.”

The social worker mentioned above says that if talks centre around “state excesses”, then the police were at the forefront. “They were locals, they had to prove to their bosses that they were more loyal than the king. Through the 1990s and 2000s, the police also recruited former militants into their ranks to quell insurgency…those people would be the most notorious.”

“But it is also true that if there is any force that has quelled insurgency the most, it is the police,” the social worker says. “It is the intimate enemy,” after all, he says using the title of political psychologist Ashis Nandy’s famous book published in 1983.

Also Read: 9 ‘Jaish sympathisers who facilitated terror infiltration’ arrested in J&K, booked under Enemy Act

Between death & duty

Mujtaba agrees about the situation. While the army and the CRPF have anonymity in Kashmir, the police don’t have that luxury, he says. “Everyone knows you and knows you intimately…You, your family are always at risk.”

Before he was killed in 2016, which burst Kashmir up into flames, militant Burhan Wani had appealed to the police to not work against their own people. Kashmiri policemen, he said, were part of the “Kashmiri nation”, and that they (militants) do not want to harm them or their families.

“Our police, despite being our own, have taken up the Indian gun against us…We appeal to them not to do this,” the Hizbul Mujahideen commander said in a video message in 2015. The policemen harass “our families”, he said, and the militants could do the same. “(But) our religion doesn’t allow us… we regard their families as our own.”

Yet, the police have often remained the first target of the militants and even angry locals. According to sources in the J&K police, since the beginning of militancy in 1989, 1,900 policemen have been killed in counter-insurgency, and 10,000 injured in gunfire, IEDs, grenades, and stone pelting.

Watali was, of course, in a sense, the militants’ first target. But while he survived the attack, a year or so later, his younger brother, Dr. Gulshan Watali, did not. “Watali sahib’s brother was killed in the most heart-wrenching way possible…of course, it was because Watali sahib was in the police,” recalls the KPS officer. “He was like his own son…Even now, if you sit with him long enough, he will start talking about him.”

But the early 1990s were just the beginning. The bloody cycle of hatred and violence involving the police, the militants, and the locals continued for years to come.

“I joined the police in 2000…Those were very difficult years. In 2008, we had to lathi-charge people during the Amarnath land transfer agitation,” recalls a head constable.

Violent demonstrations had swept the Valley after in May 2008, when the Centre and the J&K government reached an agreement to transfer 99 acres of forest land to the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board (SASB) in the main Kashmir Valley.

“We had to lathi-charge our people. Their hatred towards us increased,” he said. “In those years, we could not even go home during the day…We used to go in the quiet of the night like criminals,” he said. “Going to family weddings and funerals was out of the question. You never knew when you would be attacked by even your own neighbours.”

There was also the guilt of working against “our own people”. “There have been mistakes at our end, too…But you have to shut your own voice, and follow the call of duty,” the constable said.

The J&K police officer quoted above says, “You don’t remain the same person once you have a gun in your hand…They are just statistics now, but whenever there used to be a news of a juloos (protest), I would shudder to think how many we will have to kill.”

Like their ilk in many parts of the country, young men often join the J&K Police for the sake of a secure government job, status and power. But that is where the similarity ends. Here in Kashmir, stories of crippling fear and social ostracization of the police abound.

“Everyone looks forward to going to their homes. We would dread it,” said a Station Head Officer (SHO) in a districts “Our family would not allow us to step out even for the namaz or to play cricket with friends because they thought we might be killed. We didn’t feel like going home. In plain clothes, and no security, we were the most vulnerable at home,” the SHO says, as he pulls out his phone to show a group chat of his batchmates from the police.

The display picture is a collage of photographs of five batchmates, who have all been killed by militants. “When one of my friends died, there was a deluge of celebratory Facebook posts…It gets depressing sometimes,” he says.

In Kashmir, another SHO says, nobody wanted to marry their daughters off to policemen. “There was such a stigma that women would say ‘we will a marry a mulazim (servant), but not a policeman’,” he says. “Kashmiris always hated us. But the sad truth is that if we go to Delhi, we will also be asked to say ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ to prove our loyalty to the nation,” he adds with a wry smile. “Kashmiri police dhobi ke kutte jaisi hai, madam, na ghar ki, na ghat ki.”

The police’s moment of ‘glory’

On 5 August, 2019, when Union Home Minister Amit Shah arrived in Parliament with a ‘TOP SECRET’ document, one sentence reportedly popped out: ‘Possibility of violent disobedience in sections of uniformed personnel.’

“It was only a possibility delineated in the file because the government had to prepare for all circumstances,” a serving police officer says. “But nothing of this sort happened. You tell me of one incident where the police would have rebelled.”

Asked if he, like some other Kashmiris, felt betrayed over the abrogation of Article 370, the police officer said: “Even if there would have been some feeling at the back of my mind, I know I am firmly on the other side of the fence…Through years of service, even our funerals have been targeted. How can I side with those people now?”

The change in the status of Jammu and Kashmir from a state to a Union Territory ensured that the police force constituted largely by local-Muslims had to now report to the Union Home Ministry, and not the UT administration.

In March, Shah said that after elections are held in the UT, the central troops would be pulled back from J&K, and the police would exclusively be in charge. “The plan is under implementation…We have been strengthening J&K Police, which are now leading all anti-terror operations with central forces in a supporting role,” he said. “Earlier, J&K Police were not trusted by the establishment in Delhi. We have brought a qualitative change in J&K Police…they are now in the forefront of all operations; earlier the Army and central forces were taking the lead.”

The cops can feel the change.

“We are more respected than ever before. Post 2019, there is also a qualitative change in how people see us,” the serving officer says. “They don’t see us as the enemy now.”

According to him, even the nature of policing has changed. “Earlier, our modus operandi was to nab the militant with a gun. Now, we target the 20-30 people orbit around that boy to see which (Islamic) school of thought he belongs to, which mosque he went to, which Imam was he going to, which apps he used, etc…Earlier, Pakistan lived in the minds of Kashmir through media, through institutions, and their narratives. Now, we are in the game of winning the narrative war,” he says. “And the police have a crucial role in that.”

However, what the police see as increased respect in society is as easily construed as increased distance from the society. “Earlier, there were say 5,000-8,000 policemen out of 80,000 who were involved in counter-insurgency. Now, almost the entire force is being turned into a counter-insurgency force,” a local journalist explains. “Checkpoints are increasingly only being manned by the police. Their nature has completely changed…The Centre obviously trusts the police more now.”

An SHO quoted-above disagrees. As he quickly goes through a file of a local theft in his jurisdiction, he says that the police is finally returning to its original job of community policing. “People are increasingly coming to us and trusting us as their own.”

However, a junior in the police station later says in hushed whispers: “We, more than them (the senior officers), have our ear to the ground. I don’t know if people are trusting us or they have just given up.”

(Edited by Tony Rai)