New Delhi: In recent years, the race for Oxford Bookstore’s award for cover design has consisted of scrappy finalists from an unexpected publisher—the Jadavpur University Press. The humble JUP has been edging out the formidable Big Five of the publishing world each year with its careful attention to cover design.

It is also busting the prevalent image of university publishers dishing out stuffy, ponderous and jargon-heavy scholarly books. JUP’s publications are an eclectic, fun mix.

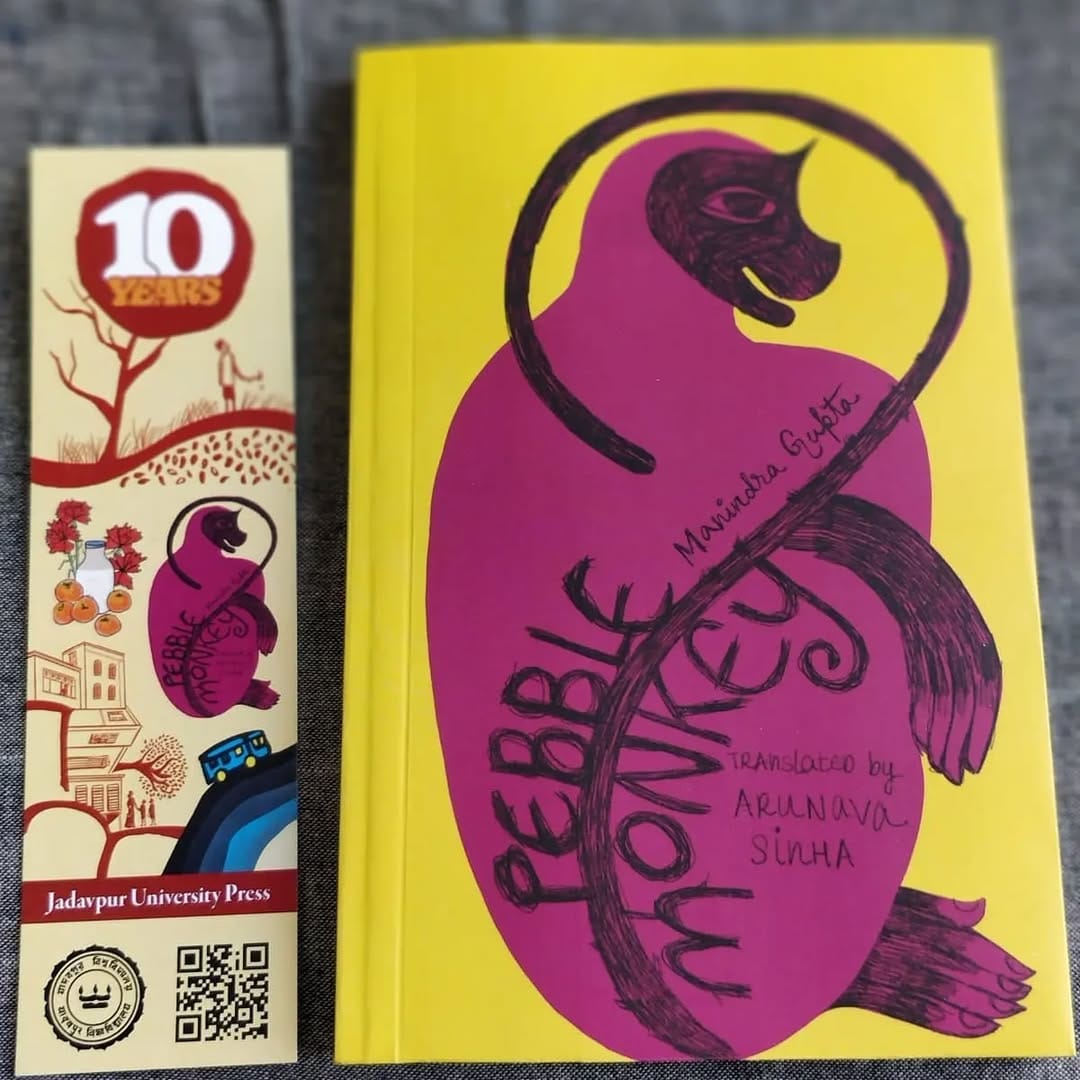

Instead of emphatic images bordering on the brash, the Jadavpur University Press works with subtle illustrations that quietly draw you in. For instance, Manindra Gupta’s Pebble Monkey, the 2023 Oxford Bookstore Book Cover Prize winner, has a pink, artfully constructed monkey into which the title blends. It is a folktale-like novel narrated by an enlightened monkey.

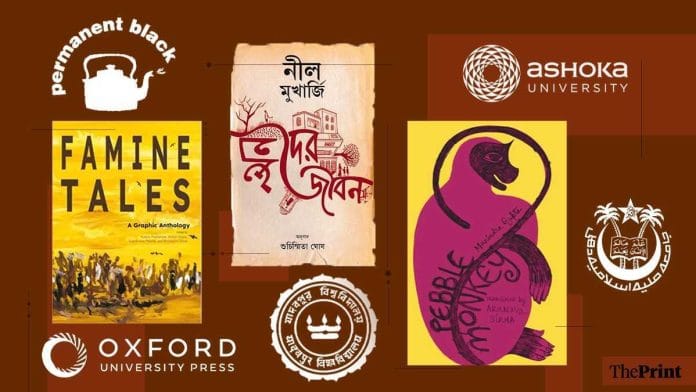

Last year had Famine Tales as a nominee, an academically rendered graphic narrative containing stories of famine from India and the UK, done in collaboration with the University of Exeter.

In a country that has lacked a robust, homegrown university publishing landscape, Jadavpur University has emerged as a gleaming exception. They publish 12 books each year, with their bestsellers entering four figures. Now, private universities are attempting to catch-up too. Ashoka University is the latest entrant in this with its imprint, Literary Activism. In order to break through the Indian publishing world of the last two decades, more and more are defying convention—going beyond the traditional model of publishing in-house academic work.

“We’re a university press cosplaying as an independent press. We inhabit an in-between space. We do academic books, and we’re also keen on publishing for the general market,” said Abhijit Gupta, Director, Jadavpur University Press. “We don’t want to churn out anthology after anthology.”

Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore and Ursula K Le Guin’s A Wizard of Battersea have found their Bangla birthplace, as has the more esoteric, such as an English translation of Kasikavrttii, a 7th-century text on Sanskrit grammar. Gupta says they take on books that “are a challenge to sell.”

This might well be the mantra of this slow moving world of university presses in India. Writer Amit Chaudhuri, now Professor of Creative Writing at Ashoka University, edits the Literary Activism, a collaboration between Ashoka University’s Centre for the Creative and the Critical and Westland Books.

Literary Activism was a project that began when Chaudhuri was teaching at the University of East Anglia. The university gave him the freedom to begin a symposium of lectures in Kolkata, which aimed to eliminate the market-wrought limits of literary imagination. The first set of papers, collected from the lectures, was published in collaboration with Boiler House Press, a UK-based small press, in 2017.

However, the project only came into its own once it began to receive funding from Ashoka University. Its website was launched in 2020, where it publishes its online magazine which includes work by various literary luminaries, like Anjum Hasan and Saikat Majumdar. Majumdar is also a professor at Ashoka.

We’re a university press cosplaying as an independent press. We inhabit an in-between space. We do academic books, and we’re also keen on publishing for the general market. We don’t want to churn out anthology after anthology.

– Abhijit Gupta, Director, Jadavpur University Press

Three years later, after publishing Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s poems in the digital magazine—Chaudhuri published Mehrotra’s Book of Rahim & Other Poems.

It marked a new beginning—a “co-production” between Ashoka University and Westland Books. The editing, marketing, and distribution are undertaken by Westland. Mehrotra hadn’t published a book of poems for the past 25 years.

“As it became more and more difficult to find a university press to publish something that was difficult to pigeonhole, Literary Activism’s website became a pathway,” said Chaudhuri.

The idea behind the enterprise is to publish books that defy strict categorisation, which would be presumably difficult to catalogue for booksellers. They could be slim volumes or tomes. But what they have in common is that they simply do not make commercial sense. This includes Chaudhuri’s long essay titled On Being Indian, the origins of which lie in a speech he gave at Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia during the CAA-NRC protests in 2019.

“We publish experimental fiction and non-fiction which is more intellectually adventurous,” said Chaudhuri.

No small feat

The Jadavpur University Press’ office is multipurpose. Located on the fringes of the university campus, it doubles up both as a bookstore and event venue. This three-pronged approach testifies to the scale of its operations—it’s a university-supported endeavour enriched by its institution, but it’s also a small press carving out space for alternative writing.

“We’re discerning about what we publish. We receive manuscripts from all over the world,” said Abhijit Gupta. “We reject more than we publish.”

They have a team of about 6-7 people, all of whom straddle multiple roles—editorial, marketing, social media. Cover designs are outsourced.

Despite this, the Jadavpur University Press published a hundred titles in 2024. Their latest work comprises a slow, meticulously compiled volume of the screenplays of late Bengali filmmaker Rituparno Ghosh, as well as a Bengali translation of Magadh, a collection of Hindi poetry by Shrikant Verma which won the Sahitya Akademi award in 1987. Magadh teems with socio-political strife, and bare-bones anger in every verse.

Magadh was translated by arguably one of India’s most prolific translators today, Arunava Sinha, who is also Professor of Practice in Creative Writing at Ashoka University. Sinha studied English literature at Jadavpur.

About 40 per cent of authors—or 50 authors—at Jadavpur University Press are in-house—both faculty members and alumni. Their catalogue includes Deborah Anne Logan’s The Indian Ladies’ Magazine and Graham Shaw’s Subaltern Squibs and Sentimental Rhymes, among others.

They are accompanied by what the unacquainted would assume to be the press’ domain—Rajat Kanti Baisya’s Makers of Jadavpur: ATechnological Perspective, and Sangeeta Datta and Subhoranjan Dasgupta’s Tagore: The World as His Nest.

“That (being an alumnus) is what initially propelled me to publish with them,” said Sinha, who is also friends with Gupta. “Things are more informal, decisions are quick and mutual. There are no battles to be fought.”

In part, this is because they aren’t driven by commercial interests, and aren’t obligated to follow trends—be it in academia or in trade publishing.

Big publishing often cannot devote enough resources to serious literature. Decision-making is on the basis of whether or not it will sell enough copies.

– Arunava Sinha, translator and Professor of Practice in Creative Writing at Ashoka University

Gupta considers them to be lucky. While the Jadavpur University name carries weight, it was only in 2012 that the press was born.

“Then VC PN Ghosh was keen on the idea of the university in print, and pushed through the necessary permissions and paperwork,” said Gupta. But they’re not bound by bureaucracy, which according to Gupta is inimical to a healthy press—wherein ideas and literature flow freely.

This freedom is palpable in their list. They receive a portion of funds from the university, but regularly apply for grants and publish collaboratively. They’re known for their translations—buying rights to texts in their original languages.

But they’re willing to invest in projects that take time, and aren’t necessarily for a mass audience. Envisaging an academic text as a graphic novel is no small feat. Nor is having a series of Bengali translations that have unlikely origins—French, German, Japanese, Nepali. This is done, of course, without winding budgets.

Despite a small team, they don’t scrimp, as is evident from carefully thought-out covers that are outwinning even their Big Five counterparts. “We work closely with printers as well. We’re fussy about these things,” said Gupta.

They do not compromise. They also just published From the Depth of the Mould: Meera Mukherjee, their first art book on the Bengali sculptor—ordinarily outside the domain of a university press.

“Increasingly I feel if a university press had the resources, I’d rather publish with them,” said Sinha. “Big publishing often cannot devote enough resources to serious literature. Decision-making is on the basis of whether or not it will sell enough copies.”

Distribution and display have always been twin challenges for small publishers, more so for university presses, who have the added burden of perception—they supposedly belong to now much-maligned ivory towers.

Walk into any big bookstore in Delhi, and there’s no chance of spotting a Jadavpur University Press title. However, they do sell at a handful of independent bookstores peppered not only across the country, but the world. Goa’s The Dogears Bookshop, Champaca Bookstore, Library and Cafe in Bangalore, and even Gosh! Comics in London.

However, other than their availability in independent bookstores—a match made in low-budget heaven—what truly makes them a small press masquerading as a university press, is the difficulty they have in selling books.

“We sell modestly—in Bengal, in Bangladesh,” said Gupta. “But we struggle overseas. We only have one overseas distributor. The biggest challenge is to sell to individual buyers outside India.”

In Bangladesh, following the uprising and the ousting of Sheikh Hasina, their sales have taken a further hit. At the same time, last year’s Frankfurt Book Fair in Germany played host to a single stall selling books in Bengali—JUP’s.

Their outreach is strong. In February 2024, at the launch of the Bengali translation of James Joyce’s Dublinnama, an intimate, besotted audience listened to Gupta reading out sections of the book at a 100-year-old house turned into a quaint cafe in Kolkata.

Survival

Jamia Millia Islamia and Jadavpur University have prestige in common, as well as being custodians of Urdu and Bengali. But when it comes to their presses, they’re worlds apart. Where Jadavpur’s press has been on the ascendant, Jamia’s has gone south.

Other than the books, the Maktaba Jamia bookstore, the once-venerable press of Jamia Millia Islamia, is lined with a centimetre-thick layer of dust. Once the nucleus of Urdu literature and publishing, it hasn’t received funds in five years.

“It’s been three years since a new book entered the shop. And three years since I last received my salary,” said Bakhtur Rai, shopkeeper at Maktaba. “I’ve eaten into my provident fund. Other employees have taken up jobs as e-rickshaw drivers.”

The death of Maktaba isn’t a cliche tribute to a decline in Urdu readership—its inability to survive runs deeper. It’s proof of a university press’ inability to keep pace with a fast-evolving publishing landscape, and the very picture of administrative apathy.

“The university press can only really survive if it is seen as a culturally valuable institution,” said Rukun Advani, previously editor at Oxford University Press and founder of academic publishing house Permanent Black. “You have to view it like the British Council (as it once was) or like the Goethe Institute of Germany—as an institution that is worth financing because it represents cultural capital and adds value to the intellectual life of a country.”

Urdu literature stalwart, 91-year-old Sadiq-Ur-Rahman Kidwai, recalled publishing four books with Maktaba—effectively one book a decade, starting in the 50s. Maktaba has a rich history to capitalise on, having been essential to Urdu literature and scholarship as a discipline. It translated Nehru’s and Gandhi’s works into Urdu, as well as of international thinkers. It was also known for its children’s books. For a recently retired professor of English at Jamia, her first introduction to Urdu was through limericks published by Maktaba.

According to Kidwai, who has spent his entire life in the lanes of Jamia, it isn’t that complicated.

“Jamia needed books, so Maktaba was started. When it couldn’t manage Maktaba, it gave it up,” he said. “If the present administration takes charge and appoints staff, it can be revived.”

In its heyday, when Urdu writers were lining up to get published by Maktaba, it was also due to its manager, Shahid Ali Khan.

“He was a classic person. I can’t imagine someone who would devote themselves to books like that,” said noted translator Anisur Rahman. “After he left, Maktaba suffered. They could never find someone else of his calibre.” Khan retired in the early 2000s, and passed away in 2021 at the age of 89. According to Rahman, those who came after him weren’t trained in publishing.

Like Chaudhuri and Literary Activism, Gupta and the JUP, the identity and functioning of Maktaba was also tied to an individual, and not an institution. Rahman compared Maktaba to a hapless child in search of their parents.

Academic and mainstream publishing

Meanwhile, the relatively young Ashoka University has three imprints—each of which has an external publisher. Literary Activism is with Westland, Center for Translation has published with Penguin and Zubaan, while Chancellor Rudrangshu Mukherjee’s The Hedgehog and Fox series partnered with Permanent Black. Of these, only Permanent Black describes itself as an academic publisher. It’s straddling two worlds.

According to Arunava Sinha, the university currently has no plans to establish an in-house press.

On the outset, the line between academic and mainstream publishing appears to be blurring. But in India, they’ve never been watertight categories. Largely because it was never a booming universe, as is the case with the West.

“In our part of the world, where there has been a relatively low level of funding for and interest in nurturing high-quality university life, there has been virtually no interest in creating and sustaining a university press as an essential part of a good university,” said Rukun Advani.

Leading universities like Delhi University and JNU have never had a press. DU only had a printing press, which was used to print examination papers and answering sheets.

“We’re a university known for its undergraduate teaching, the focus is not on research and publishing books,” said Abha Dev Habib, a professor at Miranda House. “Things have changed, but now everyone wants to publish for promotions.”

So-called academic publishing in India also became home turf for British companies, which also divested themselves of their university origins.

“Non-academic readers have seldom been interested in purchasing academic tomes. There is no reason to blame them: such books are not intended for audiences outside university campuses.”

– Rukun Advani, founder of academic publishing house Permanent Black

“While they did do a certain number of academic books, these publishing houses were not linked to universities,” said Urvashi Butalia, founder of feminist publishing house Zubaan, who began her career at the Oxford University Press’ production department.

The OUP ventured beyond the halls of Oxford, becoming known for a list which featured far more than just academics from the university, Butalia said. It consisted of Jim Corbett, Salim Ali, and Verrier Elwin—among a host of others who shaped modern Indian thought. And as is the case with Corbett, they weren’t necessarily all academics.

According to Butalia, another reason for the stagnant university press ecosystem, other than its outliers, is the fact that in India, many universities did not initially offer PhD programs—while university presses are often formed for that reason. Then there are the logistics of it.

“Setting up a publishing house associated with a university requires bringing on editors, making all the investments a publishing house needs, then getting into commercial arrangements with distributors and it is possible the mandates of universities did not allow them to do that,” she said.

Butalia learned the tricks of the trade at OUP. She later branched off on her own, first setting up Kali for Women, and then Zubaan—two plucky feminist presses. Despite identifying otherwise, Zubaan publishes academic work, as does Yoda Press, which used to have an imprint with SAGE, an academic press which shut its India operations in 2022.

If one is to go by convention, academic books are supposed to live forever in libraries—meant for engaged, devoted readers. Not for those looking for their next airport read.

“Non-academic readers have seldom been interested in purchasing academic tomes. There is no reason to blame them: such books are not intended for audiences outside university campuses,” said Advani.

But more and more academics are choosing to write for a wider audience. Literary agent Ranjana Sengupta referred to two authors signed with A Suitable Agency—Amita Baviskar and Kanupriya Dhingra, who come from staunch academic backgrounds.

It’s a testament to a popular belief that life and literature operate side-by-side, with one nourishing the other.

“It’s good that there are overlaps. Research is so interdisciplinary now. And life cannot be confined to disciplinary silos,” said Butalia.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

I found the history of Jadavpur University Press inspiring, especially how they support emerging writers through careful manuscript editing. As someone exploring self-publishing in India, I wonder how they balance academic rigor with creative freedom. It reminds me of how a good book publishing company in India like Ritera Publishing also offers author support to help first-time authors succeed.

Jadavpur University has been an intellectual powerhouse for long. The best and brightest of Bengal flock to the university and it enjoys a solid reputation across all it’s faculties and departments. Getting into the physics/maths/statistics undergraduate program at JU is an achievement in itself.

No wonder the JU press is doing well.

Ashoka University is primarily meant for the children of elite families. Why else would anyone shell out 40 lakhs for an undergraduate degree in English literature or history? There is no way Ashoka can compete with the likes of JU or JNU.

It’s laughable to read or listen to people talking about “interdisciplinary research” and other such fancy jargons of the academic world while holding a PhD in English Literature. Research in the domain of arts and humanities hardly qualifies as research at all.

Real research is carried out by scholars in the basic sciences and mathematics. Technology and medicine too have a solid research scene with breakthroughs happening every now and then. Also, research in these domains actually has an impact on the common man’s life.

Investing in research in the arts and humanities is simply wastage of money and other resources.

In the context of this article, one must note that JUP has been successful because of the outstanding reputation of JU as a university. The depth and breadth of scholarship at JU across a vast range of subjects is awe-inspiring.

In comparison, Ashoka University is a wannabe with a singular emphasis on humanities and social sciences – quite unlikely to challenge JU. However, Ashoka’s founders have deep pockets and write blank cheques – something JU absolutely cannot.