New Delhi: It’s not every day that scientific research papers get torn apart on social media—academic exposés rarely happen there. But on 13 July, the watchdog account @spottingthespot posted over two dozen screenshots of papers, each stamped with a bold, red ‘Retracted’. All of these papers, published by the leading science journal Elsevier, carried a ‘cross mark’ confirming their retraction.

These papers had another common thread too. Regardless of the research topic—be it genetic modification or biotransformation—they all shared one co-author: Ashok Pandey, a celebrated, award-winning scientist from the Indian Institute of Toxicology Research, a branch of the government’s Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in Lucknow.

Pandey now faces serious accusations, although he denies them all. He’s been labelled a “fraud”, “corrupt editor”, and a scientist with “zero credibility”. He also currently ranks 11th on an unofficial list of authors with the most retracted papers, according to Retraction Watch, a global database tracking academic retractions.

“He already has over 43 paper retractions. Almost all the retractions are related to fraud in the handling of manuscripts,” @spottingthespot told ThePrint, asking to remain anonymous. Since @spottingthespot’s last post, two more papers by Pandey have been retracted. His count now stands at 45.

But Pandey’s case is only the thin end of the wedge. The X user claims he has a list of over 100 Indian scientists whose work has either been retracted by top scientific journals or is under investigation.

These are not empty accusations. Over the last few years, the number of Indian researchers finding a mention on the Retraction Watch has seen a sharp spike. And many of these scientists in the global “wall of shame” are associated with prestigious government institutes.

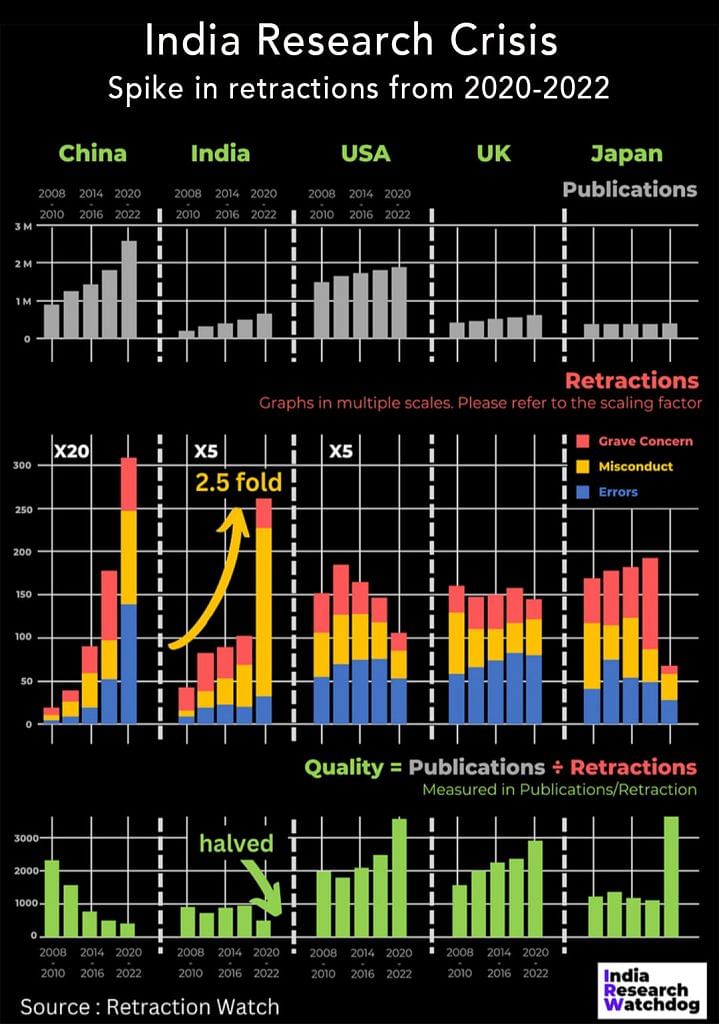

India is now wrestling with a research fraud “crisis.” Data shows that retractions from India jumped 2.5 times between 2020 and 2022 compared to 2017 and 2019. The reasons range from plagiarism to editorial conflicts to involvement in international research papermills.

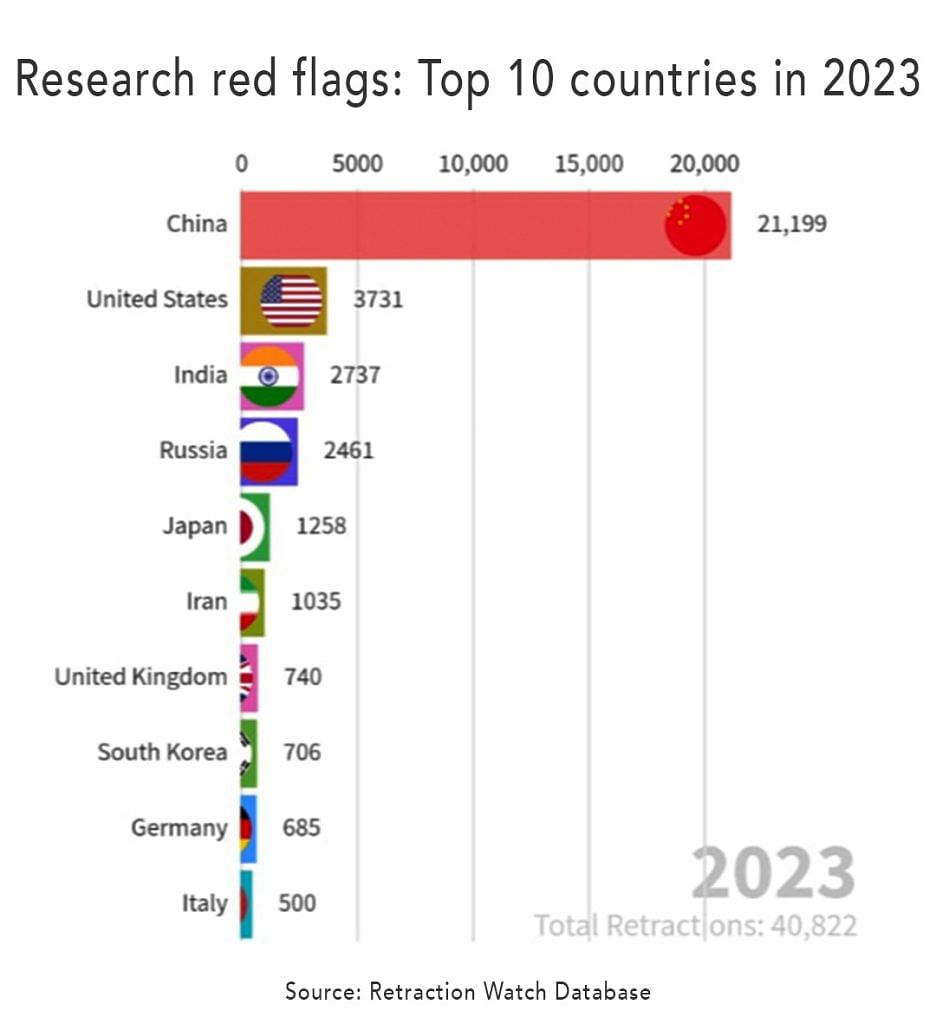

The trend has become so glaring that international watchdogs and research sleuth communities are flagging India as one of the top producers of “low-quality and fraudulent” research. As of 2023, India was behind only China and the US with 2,737 retractions, according to the Retraction Watch Database.

One such case involves Abhijit Dey, an associate professor of life sciences at Kolkata’s Presidency University. He has had at least six of his papers retracted, spanning bewilderingly diverse fields such as virology, chemistry, plant biology, and pharmacology.

Colleagues point out that Dey’s “research crimes” include plagiarism, citation manipulation, and fudging images used in his papers.

“In any other country plagiarism and getting banned from publishing in an international journal would be treated as a research crime. The scientist would be suspended and an inquiry would be called,” a senior scientist at Presidency University said. “It’s only here that tainted scientists get promotions and rewards.”

Several academic watchdogs have confirmed to ThePrint that the six retractions have, in fact, opened up a Pandora’s Box, exposing Dey’s questionable research. He has been barred from publishing new research with the journal Springer, which is now investigating more of his work.

Most people don’t think much of the work we do. They think we are internet trolls who are hellbent on maligning the image of reputed scientists. But I’d like to believe we’re academic investigators. We go on for a greater cause—cleaning up academia

-Achal Agrawal, founder, India Research Watchdog

Such allegations are serious, but most of these Indian scientists continue to thrive in their academic careers without facing consequences—a grim reflection of the state of India’s research ecosystem.

Scientists say the relentless pressure to publish is driving academic fraud. A lack of stringent scrutiny within academia is another contributing factor.

While the government and scientific institutions often turn a blind eye, many scientists warn that this trend be disastrous for India’s global reputation in the scientific community. They’re calling for stricter laws to combat these malpractices.

“The problem is that despite having such major allegations against these scientists, they continue to enjoy their position and perks. This is because we do not have stringent guidelines on how to deal with academic fraud,” said a senior scientist from Banaras Hindu University, tasked with investigating academic misconduct.

“Many of these scientists run in close quarters with their institutes’ administration, so it becomes convenient to turn a blind eye to such wrongdoings,” he added. “Institutes need to set up better quality control for research that comes from their scientists.”

In many of these retracted papers, the same groups of researchers either collaborate as co-authors or swap roles as authors and reviewers for each other. This network extends from countries like Israel and Turkey to China, Japan, and India.

Also Read: Indian PhDs, professors are paying to publish in real-sounding, fake journals. It’s a racket

Modus operandi

In a one-room ‘office’ across Delhi’s bustling Hauz Khas market, three PhD students are hard at work. They’re part of an international collaboration of volunteer “science detectives”, all on a mission to unearth the murky networks and nexuses behind retracted papers.

The three ‘detectives’, who are focusing their investigations on Indian scientists, pore over a board filled with photos, names, and memos about the authors of retracted papers across the globe.

Colour-coded strings crisscross between names, linking researchers that seem to be involved in the international research “papermill”. It looks like a TV show’s depiction of a murder investigation.

One of the PhD students explains that while some retractions stem from genuine mistakes, like typos or data errors, a worrying number are part of something much bigger—an international nexus of scammy scientists.

Some people just read the title ‘retraction’ and react. Elsevier has made such a false allegation on me—that I violated editorial ethical conduct—and in a very biased manner retracted these papers, impacting many authors from more than 10-12 countries

Ashok Pandey, academic and author of 45 retracted papers

In many of these retracted papers, the same groups of researchers either collaborate as co-authors or swap roles as authors and reviewers for each other. This network isn’t confined to one geography; it connects scientists from countries like Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, China, Japan, and India.

“If I am an author for one study, a specific scientist will be my reviewer so that the sub-standard work is cleared without any hiccups. Similarly, the next time, I will become the reviewer for the other scientist’s paper. It is an international nexus,” one of the sleuths said.

The more senior and influential scientists use their positions to commit such frauds, according to the science detectives. Editors and reviewers of international peer-reviewed journals are known to pressure young scientists to include their names as co-authors in their research to get their work published.

This, they allege, is exactly what happened with Ashok Pandey.

An Elsevier review board member told ThePrint that Pandey often added his name as a co-author after being assigned to review papers. His primary motive, they claim, was to increase his publication count and, thus, his influence in the scientific community.

Blame game

At his office in Lucknow, Pandey’s showcase is lined with accolades, medals, and framed photos of him alongside top national and international dignitaries. A former Distinguished Scientist at the Centre for Innovation and Translational Research under CSIR’s Indian Institute of Toxicology Research, he points to these as the results of his “impeccable” 47-year career.

As Pandey proudly displays his achievements, his eyes briefly well up with anger and frustration, but he quickly regains his composure. The recent retractions and what calls a “witch-hunt” have been “the worst thing that’s happened” to him.

Pandey is determined to tell his side of the story.

“I have devoted 47 years of R&D experience and earned global name and fame, with many international collaborations, recognitions, and honours. I am a person who has been teaching hundreds of researchers all around the world to follow the highest standards of ethics and be of the utmost sincerity in research,” he saiid.

Pandey was associated with Bioresource Technology, an Elsevier journal, for 21 years, including 13 as its editor-in-chief since 2011. He claims nearly all of his retractions stem from an “author-editor conflict”.

This means that the conflict occurred because he served as both co-author and reviewer on some papers, violating standard peer-review practices. While these are the only confirmed charges against him, some other papers are also under investigation.

If I am an author for one study, a specific scientist will be my reviewer so that the sub-standard work is cleared without any hiccups. Similarly, the next time, I will become the reviewer for the other scientist’s paper. It is an international nexus

-PhD student and ‘science detective’

“Ideally, for any research paper, the review is conducted by anonymous reviewers. This is to ensure that there is no bias in the review process,” said BK Singh, director of the Jabalpur-based Indian Institute of Information Technology, Design and Manufacturing.

Scientists who were part of Elsevier’s review committee during Pandey’s tenure, however, allege that the “racket” ran deeper. A review board member told ThePrint that Pandey often added his name as a co-author after being assigned to review papers. His primary motive, they claim, was to increase his publication count and, by extension, his influence in the scientific community.

Further, he would allegedly pressure young researchers into adding him as a co-author in exchange for getting their work published. For many aspiring scientists, the prestige of publishing in an international peer-reviewed journal like Elsevier was too tempting to refuse.

“In most of the papers that have now been retracted, Pandey’s name was added as a co-author post-facto,” a member of Elsevier’s review board said on the condition of anonymity, adding that this cost many young scientists their credibility.

Pandey, meanwhile, firmly denied all these allegations, insisting the retractions were not for any scientific misconduct.

“Some people just read the title ‘retraction’ and react. Elsevier has made such a false allegation on me—that I violated editorial ethical conduct—and in a very biased manner retracted these papers, impacting many authors from more than 10-12 countries,” he said.

While Pandey insists these retractions are based on ‘technicalities’, the allegations against him—manipulating authors and reviewing his own research—are serious. Still, he is standing his ground.

According to him, the manuscripts were assigned to him by the journal’s manager, and that Elsevier made him a scapegoat for a “procedural mistake”. He also contends that “jealousy” over his “global name and fame” was the real motivator.

“I never yielded to do unjustified favours to anyone. I have left IITR Lucknow because I always worked there with my head held high,” he said.

Elsevier did not respond to ThePrint’s email request for comment on Pandey’s allegations.

A paper-a-day

Another Indian researcher under scrutiny for dubious, substandard work is Professor Abhijit Dey from Kolkata’s prestigious Presidency University. His CV boasts a stellar record of “finding a cure for neurological and psychological disorders, cancer and diabetes”.

But independent science journalist Leonid Schneider paints a different picture. In a 7 May article for Better Science, Schneider questioned how, at just 43, Dey has managed to publish over 500 research papers in wildly different fields.

“Dr Dey is an expert on all forms and aspects of medicine, pharmacology, plant biology, virology, chemistry, and any other topic known to science,” Schneider wrote. He also noted that Dey’s research was “basically on whatever topic his papermill could churn out”.

Quoting a data set from one of Dey’s studies, Schneider pointed out: “Table 4 of this paper proved to have been stolen as ‘a near identical copy’ from another MDPI paper (a publisher of open-access scientific journals) by totally different set of authors.”

The allegations in this article are strongly worded and blunt, but not without a basis. Like the range of his research topics, the reasons for retraction are varied.

One of his co-authored studies, ‘Plant nutrient dynamics: a growing appreciation for the roles of micronutrients’, published in Springer in December 2023, was retracted just weeks later for plagiarism.

Scientists who have dedicated their lives to research would be able to tell you that it is next to impossible to publish 300 papers in a year. This means that (Dey) published a paper a day. Even if these were all collaborations, you can imagine the quality of research that went into these studies

-Senior Presidency University professor

“The Editor-in-chief has retracted this article because it contains material that substantially overlaps with previously published articles by different authors,” the retraction note read. “In addition, some of the scientific ideas presented by the authors can be traced back to work by others that has not been appropriately acknowledged.”

The journal noted that after the study was retracted, three authors, including Dey, contested the retraction. The rest did not respond to any communication from the journal’s editor.

Springer retracted another of his studies—titled ‘Barbaloin: an amazing chemical from the “wonder plant” with multidimensional pharmacological attributes’—in April this year

According to the retraction note, the article presented a biased view of Aloe vera’s effects, repeating the same facts throughout.

“Post-publication peer review has concluded that this article does not present a balanced review of the field: research results from other publications are overinterpreted, always in the sense of a positive presentation of the effects of the Aloe vera plant, and there is repeated presentation of the same facts,” the note said.

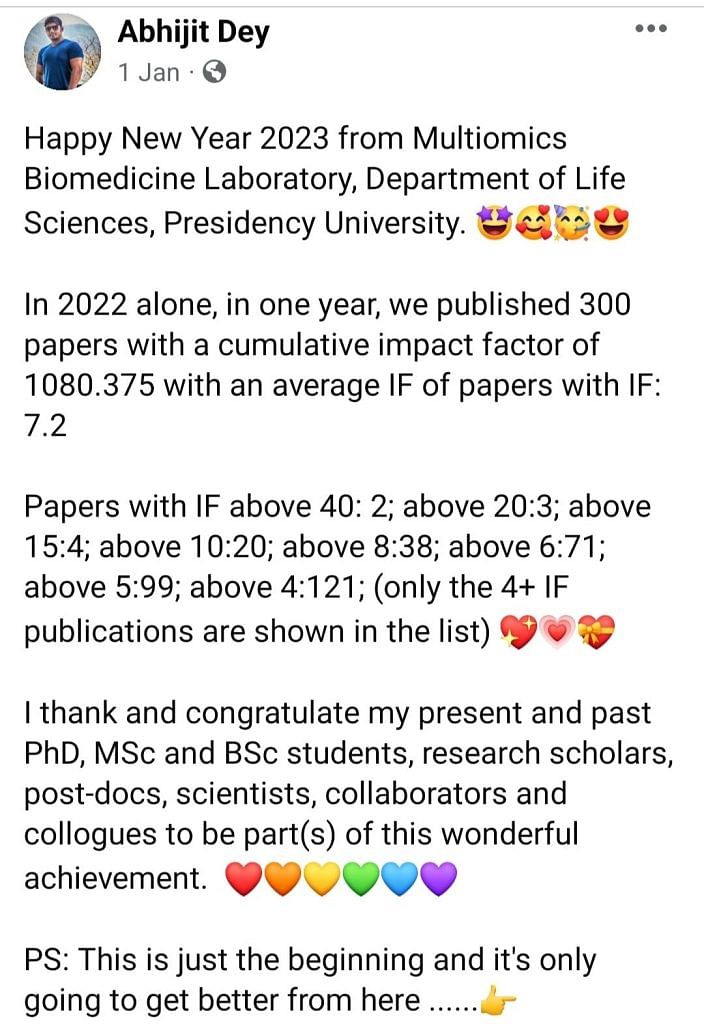

Dey’s own social media activity only raised more eyebrows. In a now-deleted post on X, he boasted about publishing 300 papers in 2022 alone, with a cumulative impact factor (IF) of over 1080.375.

Impact factor is a metric used to measure how often articles from a particular journal are cited and to evaluate the journal’s importance and quality. For scientists, the more research they publish in journals with a higher impact factor, the better their quality of research is considered.

But for Dey, the sheer volume of papers that he claimed credit for sparked suspicion.

@Sci_Spy, another whistleblower account on X, picked up on Dey’s post and began digging into his work. After finding back-to-back retractions of Dey’s work, Sci Spy started posting about the possibility of a larger academic papermill at play behind him.

“Dr Abhijit Dey publishes nearly one paper per day, mostly reviews. Last year, he published (nearly) 300 papers,” the account posted, adding that all have authors from the Middle East, South Asia, Brazil, and Spain. This, it concluded, was most likely a case of “author for sale”.

Dr. Abhijit Dey nearly publishes one paper per day, mostly reviews. Last year he published ~300 papers. All papers have authors from middle east, south asia, brazil and spain. @MicrobiomDigest @Thatsregrettab1. Most likely this is a case of @author_for_sale pic.twitter.com/qppZVhsa0n

— Sci_Spy (@spy_sci) April 22, 2023

Dey did not respond to ThePrint’s email and phone requests for clarifications on these retractions or allegations. His colleagues at the Presidency University in Kolkata, however, said that the sheer volume of research Dey produced yearly over the last few years should have been a red flag for the university to investigate his work.

“Scientists who have dedicated their lives to research would be able to tell you that it is next to impossible to publish 300 papers in a year. This means that he published a paper a day. Even if these were all collaborations, you can imagine the quality of research that went into these studies,” a senior Presidency University professor said.

Indian Research Watchdog often starts investigations after getting anonymous tips from suspect scientists’ colleagues or institutions. They “can smell BS from miles away,” reads their team description.

Panic to publish

The India Research Watchdog is a non-profit dedicated to exactly what its name suggests—sniffing out academic malpractice. Their team, made up of scientists, students, researchers, and analysts, scrutinises published work by Indian researchers for signs of fraud.

They often start investigations after getting anonymous tips from suspect scientists’ colleagues or institutions. Once a tip comes in, IRW’s volunteers verify the claims and raise alarms if malpractice is detected. They “can smell BS from miles away,” reads their team description.

IRW’s founder, Achal Agrawal, told ThePrint that India is facing a “research crisis” that’s no longer a smoking gun but a dumpster fire that people across the world can see through India’s position on retraction rankings.

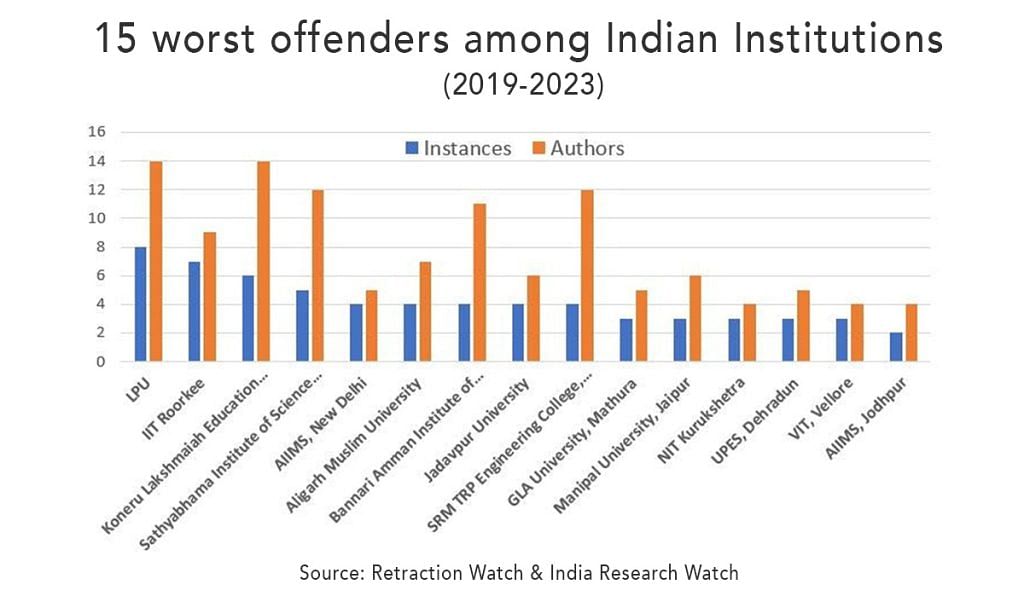

Many of these Indian authors are associated with reputed government and private institutes like the Indian Institute of Technology, Banaras Hindu University, Aligarh Muslim University, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), and University of Calcutta, among others.

Between 2020 and 2022, the field of engineering accounted for 48 per cent of all retractions, an increase from 36 per cent between 2017 and 2019, according to IRW.

To understand why academic fraud is rising, IRW also surveyed 364 scientists and academics last year. Around 35 per cent blamed unethical researchers themselves, while 10 per cent pointed to the minimal action from institutions when misconduct is flagged or caught.

Agrawal linked this trend to India’s intense focus on boosting its position in both national and international university rankings—such as the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF), QS World University Rankings, and Times Higher Education Ranking—where research output is a primary parameter.

“The focus has been on research but not necessarily on the quality of research. Promotions of faculty members in institutes are linked to the number of papers they publish. So, they only concentrate on paper writing, and in the process, the quality of education is also compromised,” Agrawal said.

He highlighted another problem—the compulsory requirement for PhD students to publish papers before they can graduate. Those struggling to do so often resort to low-quality publications or predatory journals. In some cases, students simply reword existing studies, run them through plagiarism detectors, and pass them off as original research.

IRW have flagged many cases of academic fraud, but their findings rarely result in action against the offending scientists. Often, their work is met with scorn, hostility, or, worse, silence from institutes and universities.

Also Read: Inside Indian-American biochemist’s ‘haldi swindle’ that proposed spice as ‘cancer hack’

‘Science sleuthing’

The lack of stringent action against researchers engaging in academic malpractice is fanning this fire. In many countries, regulations and rules are stricter. And some governments actively support ‘scientific sleuthing’ to ensure the quality of research coming from their academic institutes.

In China, for instance, Professor M Santosh, an Indian-origin geologist at Beijing’s China University of Geosciences, caught the attention of authorities this year after the 5GH Foundation, a local non-profit, received an anonymous tip about his unusually high productivity.

Their investigation revealed that, since 2020, nearly 65 per cent of his papers—published across four Chinese journals—were tarnished by “author-editor conflict”. This exposé not only led the Chinese government to call for an investigation into Santosh’s past work but also into the operations of the journals that published his papers.

Scientific sleuths like the 5GH Foundation have been thriving in China, with many such agencies being funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology to ensure clean and quality research.

In India, however, work done by ‘academic detectives’ is going unnoticed by the government and institutes.

For Agrawal and his team at IRW, the mission to expose fraudulent research is a lonely battle.

They’ve flagged many cases of academic fraud, but their findings rarely result in action against the offending scientists. Often, their work is met with scorn, hostility, or, worse, silence from institutes and universities. Yet, they soldier on.

IRW posts its findings on platforms like PubPeer—a global forum where users discuss and critique research after publication—in an attempt to raise awareness. And Agrawal keeps getting in touch with institutions to flag suspicious studies coming from them, no matter the lukewarm response.

“Most people don’t think much of the work we do. They think we are internet trolls who are hellbent on maligning the image of reputed scientists,” he said. “But I’d like to believe we’re academic investigators. We go on for a greater cause—cleaning up academia.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Elsevier and Springer are publishing companies, not journals

I know Dr. Ashok Pandey. He was a paper King. I think he has over 1500 publications. But according to me he was not an exta ordinary scientist but with high skills in P.R.O jobs. Earlier also he was named for plagmerism. But unfortunately in India no body want listen truth. Falsehood and favourism works.

Do you know what’s the biggest loss from such scams to the country? It’s brain drain or even worse, students interested in research will be forced to give up on taking up a career in research. The bigger issue, which this article is silent about is that, most of such research crime is actually endorsed by the academic institution managements & local political groups.