New Delhi: When 23-year-old Gayatri informed her parents she was quitting engineering to become a pilot, the turbulence began before take-off. The total price of this dream hovers around Rs 1 crore, flying schools are packed, aircraft are few, and even landing a commercial pilot licence doesn’t guarantee a job.

“I told my parents that I wanted to become a pilot in the second year of my B-Tech degree. I showed them an advertisement for a flying club, which asked for Rs 30 lakh up front,” said Gayatri. “It’s hard to get sorties because there are so many students. And the flying itself is very slow.”

India’s aviation sector is booming, with a standard declaration that there’s never been a better time to be a pilot. Air passenger traffic doubled in a decade, from 110 million to 220 million, and is projected to hit 400 million by 2029. Civil Aviation Minister K. Rammohan Naidu says India will need 4,000 more planes over the next two decades and plans to build 200 new airports.

But the numbers don’t quite add up. Fleets and runways may be expanding, but becoming a pilot is a costly, bottlenecked process.

Families take on hefty loans, sell ancestral land, and deplete savings to fund training, yet many pilots remain jobless. Some who reach the captain’s seat enjoy cushy salaries and perks, but getting there isn’t always smooth.

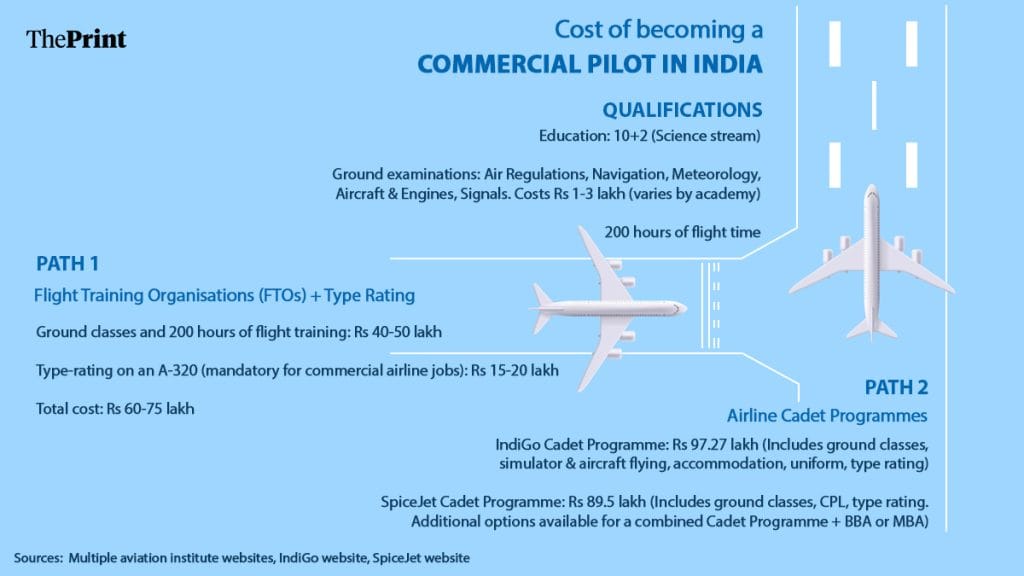

India has 38 flying training organisations (FTOs) approved by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA). These provide infrastructure and instructors to guide trainees. Students begin with ground classes, where they learn the theoretical aspects of flying. Then, they sit for examinations held by the DGCA. After this, they take about 12 months to complete 200 hours of flying—the minimum requirement for securing a Commercial Pilot Licence (CPL). The whole process costs around Rs 50 lakh.

Beyond that, pilots must obtain a type rating to fly specific aircraft—an additional Rs 15–20 lakh. Some bypass FTOs altogether, opting for airline-sponsored cadet programmes like those from IndiGo and SpiceJet, which cost closer to Rs 1 crore.

Given these hurdles, many Indian pilots now train abroad, with the Middle East, New Zealand, Australia, and the US emerging as hotspots. An aviation safety consultant told ThePrint that 60 per cent of Indian pilots now train overseas—not just for better infrastructure but because foreign training is often cheaper and faster.

“Training abroad is so much more sophisticated. The quality of planes is much better, and so are the instructors,” said a junior first officer with Indigo, who studied in Australia and Abu Dhabi. “For a student pilot, the Indian air-space is also very congested (making it harder for trainees to navigate the skies).”

A DGCA official, however, disagreed.

“Students believe that training is faster outside India, even though the quality of training is the same. In fact, India is more stringent,” said the official, asking not to be named. “It’s not fair to compare India with Western nations. They have already evolved as far as aviation is concerned.”

There are no aircraft manufacturers in India. Every single part has to be brought in from outside. Up until three years ago, aviation gasoline was also imported. That’s why flying training costs are slightly higher here

-DGCA official, who used to run an FTO

But the real crisis in India is on the jobs front. In 2023, DGCA chief Arun Kumar said that one out of three Indian pilots were unemployed due to oversupply. While 13,000 pilots were employed with domestic and international carriers, another 5,000–6,000 trained pilots were still on the market.

Even as the DGCA official quoted earlier insisted that India’s flying training industry has grown “leaps and bounds” over the past 15 years and that the aviation sector “absorbed all shocks” from COVID, he admitted that pilot vacancies haven’t kept pace with demand.

“The vacancy rate has slowed down. Airlines are announcing about 20-30 vacancies per year [which is lower than before Covid]… in a money intensive industry like this, survival is difficult,” he said.

The Covid-19 pandemic also delayed training for thousands, doubling the time needed to complete flying hours. While FTOs charge per hour flown rather than duration, the income loss hit hard. One new pilot said it took him four years to get his CPL due to Covid. Even now, landing a job takes time.

Sourabh Chaudhury, a pilot who got his CPL in 2023, called aviation “the new engineering” due to the sheer number of aspirants—many of whom “lack real passion”.

“It’s not so much about getting a job, but the delays,” said Chaudhury, who is waiting to hear from Air India Express after testing with them last month. “They announced vacancies last year but haven’t filled them due to aircraft delivery delays. There’s a backlog. It’s a backend issue.”

While demand exists, it’s mostly for experienced captains. The aviation boom is recent, and India has licensed pilots waiting in the wings—not captains.

Also Read: All you need to start a paragliding business—Rs 10k, be 21, 10th pass. And it’s turning fatal

The pilot pipeline

Gayatri had long wanted to be a pilot, but she only started chasing it after her B.Tech. Since then, the path has crisscrossed through shifting plans, setbacks, and sticker shocks. First, she considered a government-run FTO, then tried for training in the US but couldn’t get a visa, and finally settled for ground classes at a private academy. Now that it’s time to take to the skies, she’s joining an airline’s cadet programme in the hopes a job will follow right after.

“I’ve wanted to become a pilot since I first stepped foot into an airport,” she said eagerly.

The first thing Gayatri showed her parents when she decided to take the leap was a glossy advertisement for the Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Uran Akademi (IGRUA), a government-run FTO inaugurated by late Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1985. The academy, which operates under the Ministry of Civil Aviation, asked for Rs 30 lakh upfront for CPL training, not inclusive of type rating.

Her mother was aghast and her father, an engineer from Thiruvananthapuram, did not have that kind of money in hand.

“But they understood I was serious and my father was extremely supportive,” she said. When Gayatri said she’d pursue an MBA first, her father urged her not to sacrifice her dreams.

Next, they looked at training in the US, but Gayatri’s visa was rejected. With that option off the table, she joined ground classes at a coaching institute called Sahil Khurana Aviation Academy in Dwarka’s Ramphal Chowk for Rs 1.9 lakh. The clincher: students were guaranteed they’d pass.

Now, she has cleared all five of her ground examinations—the first step to becoming a pilot—and is preparing to go to Thailand as part of a cohort in Indigo’s cadet programme. But this time, the price tag is even steeper: over Rs 97 lakh.

No one has this kind of money lying around. We have to take education loans, go to moneylenders, sell land

-Junior first officer with Indigo

IndiGo was the first airline in India to launch a cadet programme, which is a one-stop shop for flight training—beginning with ground classes and leading directly to type rating. While it doesn’t guarantee a job, it offers a high chance of placement within the airline.

It’s more expensive than the conventional FTO route, but more aspirants are opting for it due to the higher quality of training and the built-in version of a campus placement programme—something FTOs lack.

Once cadet programme trainees finish, they not only have their CPL but are given priority for junior first officer positions with the airline.

The airline also assists aspirants in procuring a loan, which is a plus since not all banks offer education loans for pilot training. Gayatri isn’t sure whether she wants to take a loan and her family are still figuring out payment options.

For her, paying some additional money is worth it, since once the programme is completed, she doesn’t need to meander through the job market. But the challenge is finding the funds in the first place.

“No one has this kind of money lying around,” said the junior first officer with Indigo. “We have to take education loans, go to moneylenders, sell land.”

After exhausting other options, the junior first officer finally took an education loan from SBI.

The driving force behind this massive commitment is the promise of pay-off. The starting salary for a junior first officer is at least Rs 1 lakh. Beyond that, the smart uniform, the sunglasses, the exotic destinations, the purported prestige all add to the pull.

And there’s savvy marketing at play as well. Indigo, for instance, has carefully curated its branding—self-assured women in sleek buns, sharp suits, and market-friendly feminism. The image sells.

To pull strings for the cockpit dream, there’s a network of agents for everything. Multiple sources told ThePrint that aspirants can outsource the process of getting the computerised roll number needed to sit for the DGCA exam. These middlemen operate outside DGCA headquarters, filling forms and navigating the system on behalf of aspirants.

Their charges depend on the desperation of the client.

For acquiring a roll number, costs can go up to Rs 30,000.

Many Indian FTOs still use the Cessna 152, an American training aircraft that’s long past its prime.

Rough weather for FTOs

In late 2023, India’s biggest flying school, Redbird Aviation, went into a tailspin. In the span of six months, it saw five accidents, one of which left a trainee pilot with minor injuries after a power-related snag mid-flight. Then came accusations of corruption, with senior DGCA official Anil Gill being suspended for allegedly taking bribes that favoured Redbird.

A viral video of a crash in Baramati and a flood of bad press led to the grounding of the academy for four months and dealt a massive blow to its reputation.

But, now, a little over a year later, they’re back in full swing. Redbird currently has 45 aircraft, 450 students, and 85 instructors across five centres, giving it a major edge over most FTOs, which scrape by with just three or four planes.

“Time passed, and the dust settled. We’re back to being the largest,” said Captain Karan Mann, president of Redbird Aviation. “Our volume of flying forms 40 per cent of the country’s. If India flies 10,000 [training] hours, 4,000 are by Redbird.” Three years ago, they also established Redbird Sri Lanka, which, according to Mann, makes them the biggest FTO in South Asia.

But even as Redbird rebounds, many Indian FTOs function in precarious conditions. Fuel is more expensive than in other countries, and training aircraft must be imported.

“There are no aircraft manufacturers in India. Every single part has to be brought in from outside. Up until three years ago, aviation gasoline was also imported,” said the DGCA official, who used to run an FTO. “That’s why flying training costs are slightly higher here.”

Students experience the crunch too. With most FTOs operating with only a handful of planes, long wait times drag out training.

A freshly mown pilot from Thrissur, who took four years to complete his CPL due to the pandemic, had complained bitterly about his FTO.

“They only had 3-4 aircraft, and there were over a hundred students,” he said.

The planes themselves are another problem. Many Indian FTOs still use the Cessna 152, an American training aircraft that’s long past its prime.

The job shortage is relative. It’s a competitive field, but getting hired depends on preparation. It’s a harsh reality

-Sujit Ojha, heads of Top Training Aviation

“The last Cessna 152 was manufactured in the 1980s. I can’t believe we’re still using it,” said Redbird’s Mann.

In the US, students fly the Cessna TAA (Technically Advanced Aircraft), a more futuristic airplane — fitted with a navigation system and a multi-function display.

Over the last few years, the government has been pushing to expand pilot training within India and reduce dependence on foreign academies. In 2020, it scrapped airport royalty fees for FTOs and slashed land rental costs to encourage more training schools. Since 2021, 15 new FTO slots have been awarded across states like Assam, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu.

But for many existing FTOs, it’s been anything but smooth sailing.

India’s oldest FTO, the Delhi Flying Club, was forced to shut down in 2018 due to a legal dispute with the government over prime real estate. The closure left 85 trainee pilots in the lurch, and the pandemic only made revival harder.

After opening centres in South Extension and Mohan Singh Place in Delhi—both of which shut down—they’ve finally opened in Noida.

“We’re now again in the process of becoming a registered FTO. Attention and interest toward pilot training has increased,” said Delhi Flying Club manager Amit Sharma.

However, from its swanky Noida setup, Delhi Flying Club only offers ground classes, which start this March. Seven students have signed up so far, but Sharma expects numbers to rise after board exam results come out.

Depending on how things pan out, Sharma is looking at two options: acquiring land in Jewar to build a training airfield or renting aircraft at another airport to run flight training. A simulator is also on the way.

“We’ve wound up operations twice because it’s expensive—salaries are high in this space,” said Sharma. “But what we still have is our legacy. And high-quality instructors.”

But breaking through the market won’t be easy.

Air India is entering the fray with its own cadet programme in Amaravati, reportedly backed by a Rs 200 crore investment.

Expedited CPLs, rise of cadet programmes

Building an FTO is a risky bet, and sustaining it is even harder. Costs are enormous, marketing must be flashy enough to compete with the allure of training abroad, and now, ground schools and cadet programmes are crowding the space.

Hundreds of unregistered ground schools have sprung up in areas like Dwarka’s Ramphal Chowk, offering shortcuts that sound too good to be true. Some promise a CPL in just six months, claiming affiliations with a slew of FTOs—both domestic and international.

“It’s a serious racket. All students do is mug up past papers. All of these institutes claim to represent flying schools in the US or South Africa,” said Mann. “This practice is now discouraged by the DGCA.”

But the bigger shift is happening with airline-led cadet programmes, like the one Gayatri opted for, and their promise of an inbuilt career path.

IndiGo was the first to introduce a cadet programme in India, partnering with flying schools like Chimes Aviation in Neemuch, Madhya Pradesh, and the National Flying Training Institute in Gondia, Maharashtra. Now, Air India is entering the fray with its own cadet programme in Amaravati, reportedly backed by a Rs 200 crore investment. The airline has ordered 34 trainer aircraft, and the school is expected to open in the second half of 2025. Its target is to produce 180 commercial pilots a year.

This development has unsettled FTOs, which lose their competitive advantage with cadet programmes promising a smoother path to employment. There are fears that programmes like Air India’s will eat into the number of students who’d otherwise join an FTO.

According to the DGCA official, cadet programmes and FTOs need to develop a reciprocal relationship—operating in tandem to ensure the latter’s survival.

“What’s the point of Air India investing so much [in Amravati]? Why doesn’t it instead take over 3-4 major institutes and bring them up? And run them as per their standards,” said the official. “They don’t have to build the infrastructure. Instead, they’re killing the FTOs.”

Also Read: India’s agriculture education stuck in Green Revolution mindset

The pilot paradox

Every so often, reports warn of an impending pilot crisis in India. The most cited figure comes from aviation research agency CAPA, which estimates the country will need 10,900 additional pilots by 2030 to keep up with fleet expansion. Yet, thousands of CPL holders are still unemployed.

In 2024, the DGCA issued 1,322 commercial pilot licences—17 per cent fewer than the previous year. This followed a peak in 2023, when 1,622 pilots were licenced, nearly 40 per cent more than in 2022.

According to the DGCA official, concerns over reduced licensing are overblown, and pilots are being inducted at a reasonable clip.

“I don’t think our licencing is less,” he said. “Our induction rate is about 70 per cent which is good.”

Sujit Ojha, who heads Top Training Aviation, a Delhi-based flying academy, offered a similar assessment.

“The job shortage is relative. It’s a competitive field, but getting hired depends on preparation. It’s a harsh reality,” he said, adding that 60 per cent of his students have found jobs.

But pilots from leading airlines say the reality isn’t so rosy. They complain that vacant captain positions are increasingly being filled by foreign hires—who get better salaries and perks. While demand exists, it’s mostly for experienced captains. The aviation boom is recent, and India has licensed pilots waiting in the wings—not captains.

“You cannot have a readymade pilot. It takes 4-5 years. And to fill that gap, they’re hiring expat pilots. They cite shortages and hire people who are paid more than double. They get first-class tickets to go home. Meanwhile, no such provision exists for us,” said a pilot, who has been with the same airline for nearly nine years, speaking on condition of anonymity.

For many young pilots, the long-term goal is to leave. Several told ThePrint they harbour aspirations of working in the Middle East with airlines like Emirates and Etihad.

“It’s a personal choice. But it’s enticing. The pay is brilliant in Gulf countries. If one gets the opportunity, they’d definitely take it,” said the junior first officer.

Gayatri, despite barely having started, already knows where she wants to go.

“It’s either Emirates or Etihad. My father travels on Etihad, so there’s a special attachment,” she said. “He’s told me—‘I want to see you as an Etihad captain.’”

But it’s a herculean challenge. And for those who are seated in the cockpit, anxiety persists. India is now the world’s third-largest aviation market, yet the past five years have seen the collapse of several airlines, including Jet Airways and Go First, largely due to financial troubles.

“A lot of pilots say that it’s a passion—without even knowing what the job entails. It looks very glamorous but the industry presents so many challenges,” said a pilot with a domestic carrier on condition of anonymity. “If you have Rs 1 crore to spend, why would you become a pilot? It’s ridiculous.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Great article, should also focus on how Indian airlines are among the few in the world that impose a strict age limit of 30 years for fresh pilots, making those above this threshold ineligible to apply. This policy has disproportionately affected aspiring pilots who, due to circumstances beyond their control, have been unable to secure employment.

The collapse of Jet Airways in 2019 led to experienced pilots taking available positions in existing airlines, significantly reducing opportunities for new pilots. This situation worsened with the impact of COVID-19 and was further compounded by GoAir’s downfall in 2023. As a result, many pilots who were 24 years old in 2017 aged out of eligibility by the time hiring resumed—despite investing significant time and money in their training. This effectively creates a system of age-based discrimination, penalizing pilots for industry disruptions beyond their control.

Additionally, while media reports highlight a pilot shortage, airlines continue to overlook unemployed pilots in favor of reducing costs. Instead of hiring sufficient staff, they opt to overwork existing pilots, even challenging court-mandated rest regulations designed to ensure passenger safety and pilot well-being. Rather than investing in adequate staffing, airlines justify their stance with misleading claims that improved work conditions would reduce flight availability and increase ticket prices. In reality, these cost-cutting measures come at the expense of both safety and operational efficiency.

Well researched……mostly