New Delhi: Annie Gaur watched helplessly as the police hauled away her silver i10 Magna, which her late father had bought for the family. She had relied on it for late-night hospital runs with her ill brother, but none of that mattered now. The Magna was deemed “expired” under the government’s policy to scrap old, polluting vehicles.

No pleas or paperwork could save the car—which was just a month older than its legal age limit—from a Registered Vehicle Scrapping Facility, or RVSF.

At these graveyards for cars, vehicles are stripped to their bare frames, parts sold off piece by piece. Some owners arrive purposefully with heavy hearts and bid farewell to their beloved rides. Others bring their cars here for repairs, only to discover they’ve entered the scrapyard of no return. And some, like Gaur, land here after their cars are impounded, with no reprieve and a “nightmare” of wrangling with the authorities and scrap dealers.

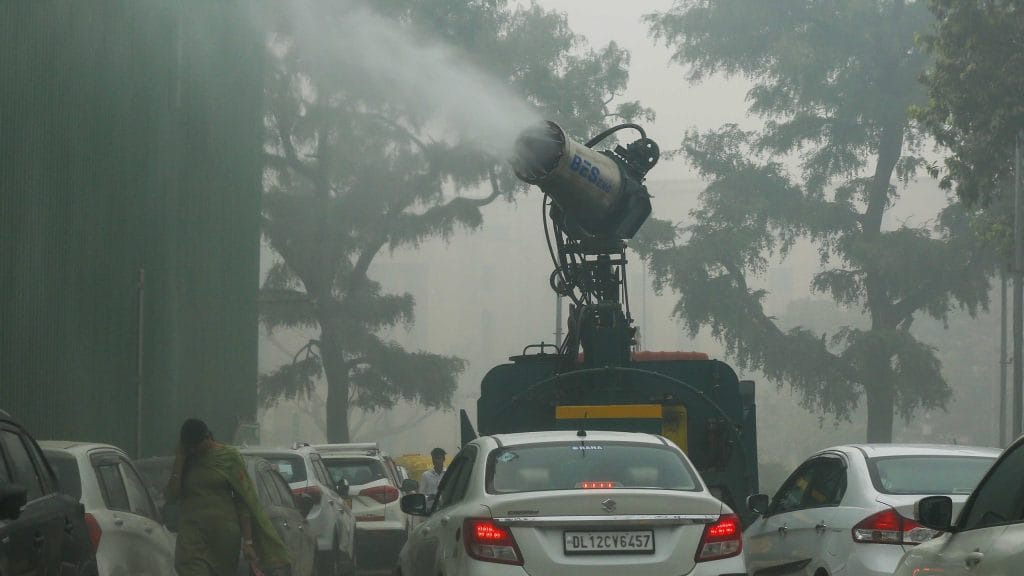

In 2021, India launched the Vehicle Scrapping Policy, a nationwide drive to retire unfit and polluting vehicles for cleaner air and a sustainable future. Delhi, choking on toxic smog, had already taken the lead years earlier. In 2014, the National Green Tribunal banned petrol vehicles over 15 years old and diesel ones over 10 years old in the National Capital Region. The Supreme Court upheld the ban in 2018, setting the stage for the 2021 national policy.

If the objective is to reduce air pollution and improve public health, vehicles should meet the stringent emissions standards of newer models, not just pass a fitness test

-Amit Bhatt, managing director, ICCT India

However, even as cars are being impounded and deregistered at a rapid rate, scrapping is another story. As of October 2024, 5.9 million vehicles have been de-registered in Delhi, but only 140,342 have been scrapped, according to the Delhi Statistical Handbook 2023. Scrapping centres, grappling with storage crises and financial losses, accuse the government of poor implementation and favouritism. And experts say the policy is failing its core goal: reducing emissions.

“The Vehicle Scrapping Policy feels adhi-adhuri (incomplete), failing both the environment and the people it aimed to serve,” said Gopal Krishan, general manager of Select Technical Services, an RVSF in Chandigarh listed with the Delhi Transport Department. “We pay 18 per cent GST to the government, yet most of us are operating at a loss. Many RVSF owners are drowning in debt.”

Despite promises of discounts and no registration charges on new vehicles, concession on Road Tax, tradable COD (Certificate of Deposit), and a cleaner environment, its impact has been underwhelming. Poor implementation, lack of awareness among vehicle owners, and the temptation of higher payouts from unauthorised scrappers have undercut its goals.

“Most people don’t bother deregistering their vehicles because they don’t know about the scheme’s benefits,” said Krishan. “Despite the government efforts to offer tax rebates and monetary benefits, the immediate payout from local scrappers proves more enticing for many.”

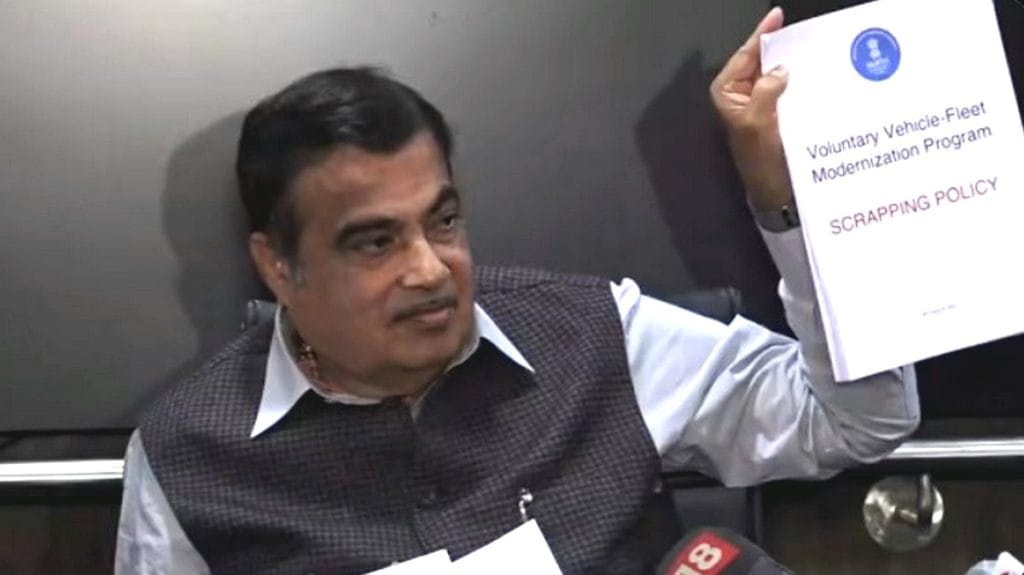

To address these gaps, the government is working on a revised policy, moving from age-based scrapping to fitness-based criteria, with stricter emissions checks. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) has also introduced new incentives for scrapping older vehicles, such as waivers for pending liabilities. Last August, Minister of MorTH Nitin Gadkari announced that carmakers have agreed to offer bigger discounts on new vehicles to owners with a valid scrapping COD.

But some experts warn that basic fitness tests alone won’t curb pollution—vehicles must meet the latest emissions standards.

“If the objective is to reduce air pollution and improve public health, vehicles should meet the stringent emissions standards of newer models, not just pass a fitness test,” said Amit Bhatt, managing director of the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) India.

He added that vehicles with outdated standards, like Bharat Stage (BS) 2 and 3, pose a significant environmental risk, and keeping them on the road undermines pollution control efforts.

“Older vehicles, even if they pass, still emit significantly higher pollution compared to BS6 vehicles,” he said. “Therefore, only those that meet the latest standards should be allowed to run; others should be scrapped.”

On paper, Delhi’s crackdown on older vehicles looks swift and decisive. But behind the growing impound figures lies a tangle of confusion and grey areas.

Also Read: A new automobile scrappage policy is needed. Link it with emissions

‘Graveyards’ overflowing, scrapping stalled

On a two-acre plot in Ghaziabad, rusting vehicles are crammed together, many barely recognisable with mangled frames. Most are covered in a thick layer of dust. While the space is organised, it’s fast running out of room.

“Many scrappage centre owners were unofficially instructed by the Delhi Transport Department not to scrap end-of-life impounded vehicles for 90 days,” said Saif Uddin Khan, owner of Saral Auto Scrapping India. “I pay Rs 7 lakh in rent every month. I even had to buy an additional 3-acre plot (nearby) because my current site was too cramped.”

Khan’s centre, which employs around 200 workers, has hundreds of vehicles waiting to be scrapped.

According to official guidelines, owners of impounded vehicles have three weeks to submit an application to the Delhi Transport Department to request the release of the vehicle, preventing it from being scrapped. The department is required to respond with a decision within one week.

Khan, however, claims that the process is far slower than this.

“Applications are being approved after 28 days. The guidelines are not being implemented yet,” he alleged. “What if the vehicle had already been scrapped by the time the application was processed?”

The Transport Department said it is working toward streamlining things.

“The online application for the release of vehicles was launched in the last week of October. However, operational issues require constant upgrades and resolution,” said Sachin Shinde, special commissioner of the Delhi Transport Department. “The portal is being modified to allow access to all RVSFs within a week, which will help bridge any communication gaps between the department and RVSFs regarding the release or scrapping of vehicles.”

The effectiveness of this scheme is evident in the data. It’s all about making people aware of their responsibilities and the benefits of scrapping their old vehicles

-Sachin Shinde, special commissioner, Delhi Transport Department.

Scrapping centres also face challenges in acquiring vehicles. RVSFs source vehicles through several government platforms, including online auctions by the Metal Scrap Trade Corporation Limited (MSTC) for government vehicles, as well as drives conducted by the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD), Delhi Traffic Police, and Enforcement Directorate.

Each centre participating in an enforcement drive is assigned a specific MCD zone, entitling it to vehicles from that area. According to the guidelines, enforcement agencies must distribute and utilise scrapping facilities equitably among all RVSFs participating in the drive.

But some scrapping centre owners allege preferential treatment by the traffic police.

“The centres that pay higher prices get most of the vehicles,” Khan claimed. “For each vehicle, we must pay at least Rs 500, even though the guidelines say that non-government vehicles in the drives should be handed over for free.”

Ajay Chaudhry, special commissioner of police in the Traffic Management Division, Zone-II, said they would look into the matter.

“If anything like this is happening on the ground, we will investigate it and take strict action,” he added.

Khan’s centre currently receives 12–18 vehicles daily from the drive. Through MSTC auctions, he can acquire as many vehicles as he is willing to invest in, but the process is highly competitive. All centres bid against each other, driving up prices until one secures the win.

The situation is similar at Gopal Krishan’s centre in Chandigarh, which once received 15–20 vehicles daily through government-led drives. When the policy was first introduced, scrappage centres were limited in number, and so Krishan joined the drive and was assigned the Rohini MCD Zone. However, the returns were low, especially factoring in the high cost of transporting vehicles from Delhi to Chandigarh. Three months ago, Krishan withdrew from the drive. Now, his facility relies on MSTC auctions and direct customers.

“Even the volume of government vehicles we receive through online auctions via MSTC is quite low,” said Krishan. “Scrappage centres can’t survive on that alone. We’re far more dependent on direct customers.”

Faced with complaints about how vehicles are assigned and low returns, officials say they’re shaking up the roster of scrappage centres.

“We are disengaging non-performers and actively considering new applicants who are eager to join the drive,” said Shinde. “All zone jurisdictions are allocated to the best-performing teams (RVSFs), known as Rapid Action Teams. The non-performers are given rest, and new RVSFs are brought in. Currently, around 13 new applications have been received for empanelment (in Delhi), and these proposals are under review.”

Govt perks vs quick payouts

Scrapping an old car can come with perks if the owner sticks to the official route. Yet many are junking this option.

If owners scrap their end-of-life vehicles at registered scrapping facilities, they are entitled to a certificate of deposit, or COD. This can be used to claim tax rebates on the purchase of a new vehicle: 20 per cent for non-commercial petrol or CNG vehicles, 15 per cent for commercial ones, and 10 per cent for diesel. For those not intending to purchase a new vehicle, the COD can be traded online via DigiELV, an authorised platform recognised by the MoRTH. The value of the COD is not fixed and varies based on the price set by the seller.

But many vehicle owners bypass the official scrapping facilities altogether. Instead, they head straight to local scrappers or used car dealers, lured by the prospect of better payouts.

“Even when vehicles are de-registered at Regional Transport Offices (RTOs), a significant number end up in the hands of used car dealers or unauthorised scrappers,” said Krishan. These transactions often fetch owners a higher price compared to the standardised rates offered at official scrapping centres, which rely on a formula set by the MoRTH to calculate compensation.

I’ve been through so much trouble with this car. The government doesn’t answer, and these scrap houses are just businesses out to scam people. It’s been a nightmare

-Annie Gaur, Delhi resident whose car was impounded in December

Krishan pointed to Assam as an example of a more robust system. There, it’s mandatory to obtain a certificate of deposit from an RVSF to cancel the registration certificate (RC) at the RTO.

In Delhi, however, vehicle owners can cancel their registration at the RTO without a COD from a registered scrapping facility.

“This loophole is one of the reasons why people often choose to scrap their cars at local centres, or sell them to used car dealers offering better prices,” said Krishan.

Another problem arises with vehicles that leave Delhi with a new owner after de-registration.

“These vehicles receive an NOC from the RTObut often don’t get re-registered in other states,” said Krishan. “The cost of re-registering, including the RC, insurance, and other documents, often exceeds the price paid to purchase the old vehicle.”

This is a risk to the original owner. If the vehicle is involved in a crime, the person whose name is on the RC is held responsible, Krishan warned.

Crackdowns and confusion

On paper, Delhi’s crackdown on older vehicles looks swift and decisive. But behind the growing impound figures lies a tangle of confusion and grey areas.

For Shinde of the Delhi Transport Department, the numbers speak for themselves—6,188 end-of-life vehicles were impounded in December 2024, up from 1,676 in November. On 1 January 2025 alone, a total of 238 end-of-life (EOL) vehicles were seized.

“The effectiveness of this scheme is evident in the data,” said Shinde, adding that the department regularly issues public notices and sends SMS alerts every week to EOL vehicle owners to encourage them to scrap their old vehicles. The notices also point out that no NOC will be issued for vehicles more than a year past their expiry.

“It’s all about making people aware of their responsibilities and the benefits of scrapping their old vehicles,” Shinde added.

Yet, some experts say raw impoundment data doesn’t tell the whole story. Amit Bhatt of ICCT India noted that deregistered vehicles stay on Indian roads out of state oversight and there’s still a gap in accurate data tracking on vehicle deregistration, re-registration, and scrapping.

“In an ideal scenario, the number of vehicles deregistered in Delhi should match those re-registered in other states or scrapped. Since that’s not happening, and we lack the data to identify the gap, creating a comprehensive database is crucial,” he said.

Without this, he added, deregistered vehicles that aren’t re-registered or scrapped remain on the road, contributing to air pollution and health risks.

“This data would allow for targeted actions against these vehicles,” he said.

Meanwhile, owners often complain of rock-bottom offers and red tape.

In December, Varun Kumar from Muradnagar discovered his 2009 Alto was no longer legal to drive in Delhi or the NCR.

“Where will I drive it now?” he asked. “I can’t take it to Delhi or anywhere in NCR. If it gets caught up in legal trouble, my name will come up.”

He accepted Rs 28,000 from an RVSF, far below the roughly Rs 1 lakh or more that similar cars of the same vintage list for on second-hand websites like OLX.

Annie Gaur had a more harrowing time. Her i10 Magna was impounded outside her workplace in December, a month after it hit its expiry date. The car held deep sentimental value as it once belonged to her late father so she tried to salvage it.

When she reached out to the MCD, they couldn’t offer much help, only directing her to the scrap center where the car was held. Hoping to move it out of Delhi for a better resale, she requested an NOC from the RTO; however, she was turned down—even though guidelines allow owners up to a year after expiry to obtain an NOC to allow relocation to areas where such vehicles are allowed.

And at Nirvana Scrapper in Ghaziabad, she alleged she was quoted Rs 17,000 after the staff “just googled” a price without weighing the car. They also denied her a COD because her car had been impounded by the government.

“I’ve been through so much trouble with this car. The government doesn’t answer, and these scrap houses are just businesses out to scam people. It’s been a nightmare,” Gaur said.

Also Read: A to Z of AQI—Why Delhi can’t breathe easy

Beyond the Scrapyard

Some owners are anxious about what happens to their vehicles once they enter the scrapping centre.

On a December afternoon, one such customer arrived at Saral Auto Scrapping with his 2009 Wagon R, insisting on a video of his car’s destruction.

“How else will we know if our car has been scrapped? What if they sell it off? That would cause us trouble,” he said.

Proprietor Saif Uddin Khan offered Rs 32,000 for the vehicle, and then also explained how CODs work and that they can be traded.

Although the market value of a COD isn’t fixed, Khan offered him Rs 7,000 for it, calling that the “actual value”. Khan later trades CODs for profit.

“It’s a fair practice to me. You get your due, and I earn my profit as well,” he said.

Even as the cars pile up in his facility, Khan said he glimpses a bright future in NCR’s gridlocked roads: “When there’s traffic on the road, I feel happy seeing so many vehicles, knowing that they’ll eventually make their way to our centre to be scrapped.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)