New Delhi/Ambala: The atmosphere at the Delhi Waqf Board office is tense these days. Staff and budget shortages are huge stressors, but the greatest fear is venturing out into the field. On a recent afternoon, an argument broke out over a routine task— surveying a waqf site in Malviya Nagar.

“I won’t go there alone, it’s not safe. Please send two or three people with me and provide security,” the officer designated for the job told his senior. “There is a lot of public aggression. They call us encroachers and corrupt.”

Name-calling isn’t the only worry for waqf officers when they visit sites for inspections, meet mutawallis (caretakers), or conduct checks on the income generated from a property. The negative public perception of waqf boards as avaricious land-grabbers has grown so much in recent years that a few officers have even been physically attacked.

Scrutiny and pressure on waqf boards are at an all-time high. Following the Babri Masjid controversy, highly charged disputes have arisen around Varanasi’s Gyanvapi mosque, Mathura’s Shahi Eidgah, and Delhi’s Sunehri Masjid, causing anxiety within the Muslim community about their hold on their religious heritage sites.

As social and political bias toward these properties rises, Waqf boards are reeling internally under legal cases, acute staff shortages, political appointments, widespread encroachment, and distressing demolitions. Political demands to abolish Waqf and its laws are gaining momentum, but many in the Muslim community are also appalled at alleged mismanagement of rents from these properties and demanding reforms.

Between abolishment and reform, waqf boards today are fighting a desperate battle for identity and relevance in a changing India.

“There has been a sharp increase in litigation cases in the last five years,” said the senior official at the Delhi Waqf Board (DWB).

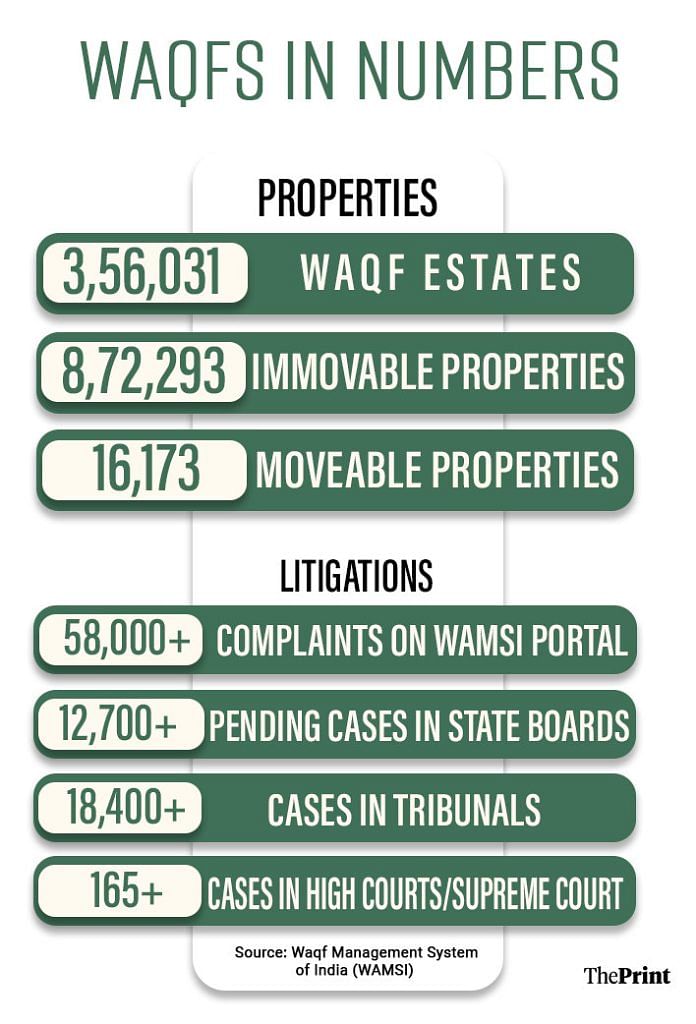

In many parts of India, resentment simmers over the perceived wealth and power wielded by waqf boards, the country’s third-largest landowner after the Indian Railways and armed forces. Currently, there are over 8.72 lakh immovable waqf properties listed on the Waqf Management System of India (WAMSI) portal of the Union Ministry of Minority Affairs, ranging from graveyards and mosques to orchards and educational institutions.

They (government agencies and media) have defamed us so much. This has led to an increase in attacks

-Delhi Waqf Board official

Waqf properties are lands or assets donated for religious or charitable causes per Islamic law, and managed by boards to ensure appropriate use and deployment of proceeds for the greater good. Currently, 32 waqf boards function across India, each overseeing such properties within their respective state or Union territory.

However, waqf properties are more than simple transactions between a donor and an executing board. They are often tangled up in messy disputes. Some cry foul over mismanagement and financial irregularities, while others question if a property was rightfully donated. Communal tensions, political controversies, and hostile narratives complicate matters even more.

“People feel that we have come to grab their lands. But the reality is that we ourselves are not able to save our property,” said the senior Delhi Waqf Board official.

Waqf boards not only manage existing waqf properties but also take steps to recover any that might have been ‘lost’. This has often been interpreted in fear as the board having the power to declare any land as its own.

Also Read: In Ajmer maulana killing, children got the better of cops. Spotlight now on madrasa safety

Losing the narrative battle

Tucked away in a yellowing building in Old Delhi’s Daryaganj, the office of the Delhi Waqf Board looks modern inside, with computers and swivel chairs. Sixty-four people still work here, but many desks sit empty, a sign of the board’s woeful staff shortage after 150 employees were dismissed last year. This makes managing the 2,000-odd properties under its care—residential buildings, shops, mosques, schools, and more—a monumental task.

Their biggest challenge, though, isn’t physical; it’s a relentless tide of negative publicity that has been shredding their reputation and even triggered a few aggressive confrontations during property surveys and encroachment checks.

A 37-year-old staff member shuddered as he recalled a harrowing survey near Lok Nayak Hospital in central Delhi. Around six men, armed with sticks, surrounded him and his colleague, accusing them of land grabbing and assaulting them. Both were injured.

Another official recounted a similar incident from March last year at Tikona Qabristan in Nizammudin, where five people surrounded and prevented him from conducting a survey.

There have been other instances of other hostile receptions too and employees now go in groups to prevent attacks.

“They (government agencies and media) have defamed us so much. This has led to an increase in attacks,” said the official who had gone to Nizamuddin.

Their boss, the senior Delhi Waqf Board official quoted earlier, stressed that the portrayal of waqf boards as encroachers is false.

“We have enough property. We don’t need to encroach on others,” he said.

However, the backlash is only mounting, from a demonstration led by then Delhi BJP chief Adesh Gupta in 2022 to a petition in the Supreme Court by lawyer and BJP leader Ashwini Upadhyay to scrap the Waqf Act on the ground that it was discriminatory towards other religions.

Angry rhetoric from BJP leaders has been adding fuel to the fire. For instance, last month, BJP MP Sudhanshu Trivedi claimed that Congress leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and Rajiv Gandhi had empowered the waqf board so much that it now holds more land than any government department. “You can’t talk about the right to resources; you have already given it away,” he said.

‘Once a waqf, always a waqf’

For some waqf officials, countering “wrong” narratives is among their top priorities.

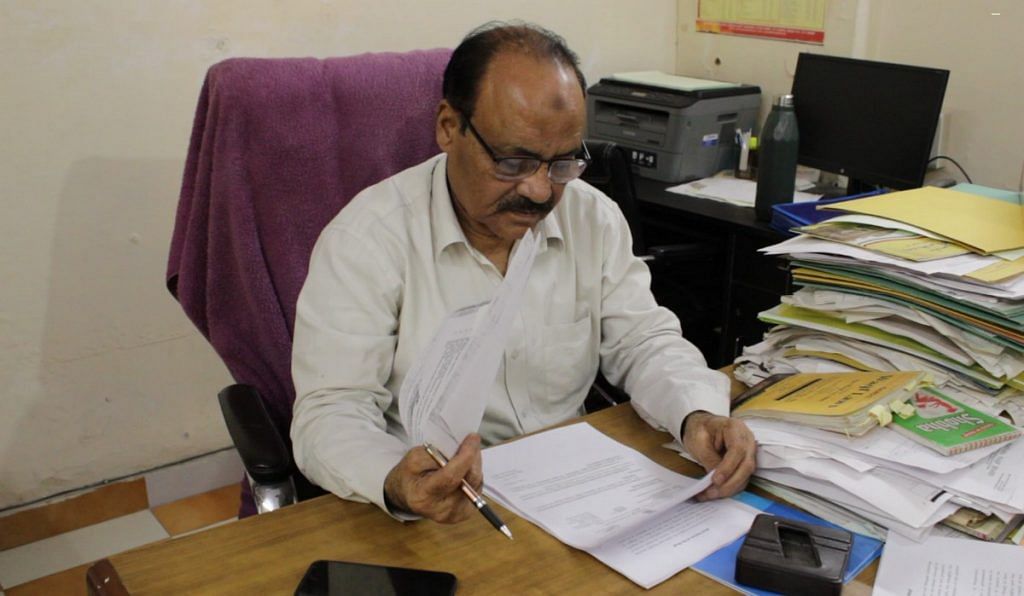

Iqbal Khan, senior legal officer of the Haryana Waqf Board, has taken up this task with determination. In his room at the waqf office in Ambala—a colonial-era bungalow that was abandoned during Partition—he sifts through social media videos to identify misinformation.

Within seconds of watching one YouTube video, he flagged a problematic statement—the male voiceover proclaiming that all of Haryana’s property came under waqf after Partition. This was incorrect since the waqf received only properties like mosques, graveyards, shrines, and madrasas, all recorded in revenue documents, he said.

To counter “wrong” narratives, Khan is compiling an 8-page booklet. The document explains the concept of waqf, its history in India, the relevant laws, rights, and jurisdiction, properties eligible for waqf ownership claims, and the process of designating lands as waqf properties.

Today’s waqf system has its roots in the aftermath of Partition. In 1950, India passed the Administration of Evacuee Property Act, under which properties that belonged to Muslims who had left for Pakistan, including Waqf assets, were placed under a Custodian Department. These properties were then rented out to refugees from Pakistan at low rates, forming a Waqf tenants’ system in India.

In 1954, the Jawaharlal Nehru government passed the Waqf Act to manage these properties, which led to the centralisation of waqfs. Then in 1995, a new Waqf Act was passed, and then further amended in 2013, giving the boards greater control.

We can’t claim any land as our own. We are unable to manage even our gazetted lands. We can only claim the land that is recorded in the revenue department’s records before Partition. We have to prove those lands as ours too.

-Iqbal Khan, Haryana Waqf Board

The abiding principle, derived from Sharia law, is: “Once a waqf, always a waqf.” Boards not only manage existing waqf properties but also take steps to recover any that might have been ‘lost’ or that they may regard as waqf, invoking the Act’s controversial Clause 40.

This has often been interpreted in fear as the board having the power to declare any land as its own.

Last December, Clause 40 was at the centre of a private bill introduced by BJP Rajya Sabha MP Harnath Singh Yadav to repeal the Waqf Board Act of 1995. In a tense voting session, 53 members voted in favour of the bill and 32 against it.

Speaking to ThePrint, Yadav described the Waqf Board Act, 1995, as an “atrocious” law that increases discord in society and allows misuse of power.

“During Partition, there was an agreement between India and Pakistan that Muslim properties in India would be given to Hindus, and Hindu properties in Pakistan would be given to Muslims,” Yadav said. Instead, he added, political “conspiracies” warped the system, leading to land allocations to the waqf.

He claimed that many properties nationwide have been forcibly taken over by the boards and argued that the Act shifts the burden of proving ownership onto the current owner, while Waqf orders can’t be challenged in court.

“This country is supposed to be run by the Constitution. This law is unconstitutional and illogical. The people of the waqf boards have created havoc across the country. We want this law to be abolished,” he said.

Iqbal Khan, however, disputed this characterisation.

“We can’t claim any land as our own. Due to various shortcomings, we are unable to manage even our gazetted lands,” Khan said. “We can only claim the land that is recorded in the revenue department’s records before Partition. We have to prove those lands as ours too.”

The 2006 Sachar Committee report revealed that waqf boards possess land worth Rs 1.2 lakh crore, which could generate Rs 12,000 crore annually for the upliftment of Muslims. Instead, they managed only Rs 163 crore.

Increasing litigation

What is happening in Delhi is a whole different ballgame.

While Waqf employees are called encroachers, the Delhi Waqf Board has another problem— protecting its own land from encroachers.

The Delhi Waqf Board is embroiled in a dispute with multiple agencies—the Delhi Development Authority (DDA), the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and the Land and Development Office (L&DO).

According to a senior DWB official, these institutions often lay claim to waqf lands, leading to a rise in conflicts.

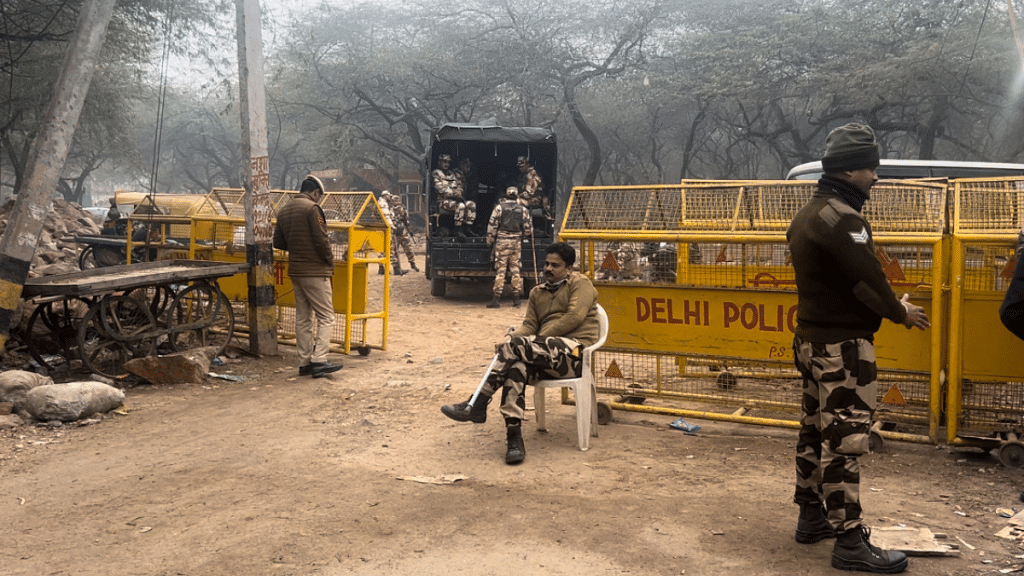

The DDA is the dreaded acronym for the Delhi Waqf Board. Over the last year or so, it has demolished several mosques on the grounds that the structures were illegally constructed.

The list includes the nearly 600-year-old Akhunji Mosque in January, the 900-year-old Baba Haji Rozbih dargah in Mehrauli in February, and the 200-year-old Nanhe Mian Chishti Dargah in Mandi House, which was demolished in April 2023.

Another flashpoint came in February last year when the central government, through the L&DO, issued an order to seize control of 123 Waqf properties. The DWB has challenged this in the Delhi High Court, citing a 2014 notification under the UPA government that allocated these properties to them.

This is not the only ongoing battle. The DWB, with the backing of other Muslim organisations, is locked in a continuous struggle to maintain control over waqf properties.

Currently, more than 58,000 complaints on the WAMSI portal are related to land disputes over Waqf properties. There are over 12,700 pending cases before state waqf boards, another 18,400 cases in waqf tribunals, and 165 cases in various high courts and the Supreme Court.

“Most of the cases we see are related to (waqf) property over which the authorities are claiming ownership rights,” said Delhi High Court advocate Farhat Jahan, who handles numerous waqf-related cases.

Jahan points to a lack of strong legal representation for the waqf board as a major factor in authorities often getting the upper hand. However, others like Iqbal Khan also blame this state of affairs on corruption and disinterest among some waqf employees, as well as the influence exerted by “political appointments” to the boards.

Despite their frustrations with the waqf boards, many Muslims favour reform over abolition. For them, waqf boards play a crucial role in maintaining religious sites and providing social welfare services.

‘Political appointments’

In a stately white building in Delhi’s Abul Fazal Enclave, Inam-ur-Rahman’s office seems hit by a storm of Right to Information (RTI) requests and legal cases concerning waqf properties.

Rahman, the assistant secretary of Jamaat-e-Islami, oversees waqf-related issues, with a focus on protecting mosques, and also lends a hand in legal cases. One such battle was a petition seeking the removal of Ashwani Kumar, the principal secretary (Home) of the Delhi government, as the administrator of the Delhi Waqf Board.

Filed in April by the Secular Front of Lawyers, the petition claimed Kumar’s appointment was “illegal, arbitrary, and against the board’s conflict of interest”. The PIL also alleged that instead of safeguarding the Waqf properties, the administrator was trying to “destroy” them. The matter is currently under the consideration of a Delhi High Court bench. Last month, however, the court quashed another similar petition and imposed a fine of Rs 10,000, calling it a “publicity-oriented litigation”.

For Rahman, the demolition of heritage waqf structures in Delhi is a sign of hostile forces at play.

“Kumar, as principal secretary, is granting permission to demolish mosques and dargahs. How can he, as the waqf administrator, protect its property? It’s a contradiction,” Rahman said as he left the court’s premises last month.

This is not the only controversy to have arisen over alleged political appointments being made to waqf boards.

Political appointments have caused more harm. They start thinking of themselves as badshahs and act arbitrarily

-Inam-ur-Rahman, assistant secy of Jamaat-e-Islami

For instance, in February, the Gujarat BJP’s minority wing president Mohsin Lokhandwala was elected unopposed to the state waqf board. This followed just over three months after the state government notified the appointment of five members, four of whom were from the BJP, to the Gujarat waqf board. Similarly, in 2022, BJP leaders Darakhshan Andrabi and Shadab Shams were appointed chairpersons of the J&K and Uttarakhand waqf boards respectively.

Rahman claimed that waqf appointees with political ties worked with agendas other than the interest of the board. He also alleged some used waqf properties for “personal purposes” such as opening offices and renting them out.

“Political appointments have caused more harm. They start thinking of themselves as badshahs and act arbitrarily,” he added.

Haryana Waqf Board’s Khan also claimed that such appointments not only affect the functioning of the board, but also increase the chances of “corruption”, with politicians, middlemen, and waqf officials forming a nexus.

In a high-profile case from 2019, Uttar Pradesh Sunni Waqf Board chairman Zufar Ahmad Farooqui was accused of being involved in the ‘irregular’ sale, purchase, and transfer of waqf land. He was booked along with Samajwadi Party leader Azam Khan, UP Shia waqf board chairman Wasim Rizvi, and others for allegedly forging documents and fraudulently attempting to capture land under the Enemy Property Act (which regulates property in India owned by Pakistan nationals).

Rizvi converted to Hinduism in 2021 and now goes by the name Jitendra Tyagi. He describes himself as a “Sanatani Hindu warrior” in his X bio and is still president of the UP Shia Waqf Board.

Last year, another case emerged of the illegal occupation of Waqf property by relatives of the late politicians and gangsters Atiq Ahmed and his brother Ashraf in Prayagraj. Last month, after the property was freed, the UP Sunni Waqf Board opened a charitable clinic there.

Waqf officials admit to rampant corruption throughout the ranks, leading to a loss of control over land. Many of them blame the mutawalli system as a major source of corruption at the local level.

Corruption, mismanagement, mutawallis

Corruption and mismanagement allegations have dogged the Delhi Waqf Board for several years, but matters came to a head when its former chairman, Aam Aadmi Party leader Amanatullah Khan, was arrested in April in a money laundering case entailing irregularities in recruitment.

Khan’s tenure as chairman ended last August and the position remains vacant. Further chaos came in October when 150 employees were dismissed because of the cloud over their recruitment.

“The waqf has become paralysed due to absence of chairman and board members for the last 8 months. Due to this many works have stopped,” said the senior DWB official.

Waqf officials admit to rampant corruption throughout the ranks, leading to a loss of control over land. Many of them blame the mutawalli system as a major source of corruption at the local level.

Under this setup, each waqf property has a manager, called a mutawalli, who is responsible for property management and revenue collection. Their selection and recruitment is done by a committee in the waqf board.

Every state has the mutawalli system in place— except Haryana. As a result, Khan argued, there is “less corruption” there because all properties are directly managed by the Haryana Waqf Board.

We always pay more than a fixed rent. The person who collects the rent keeps the extra money and it goes to his pocket

-Robin Agarwal, member of the Sonipat Waqf Tenants’ Association

According to Khan, mutawallis at times misappropriate funds from waqf properties, such as charging tenants more than the fixed rent and pocketing the difference. Sometimes the mutawallis don’t collect rent at all. This, he explained, was because rents for many properties are outdated and extremely low, and mutawallis may barter rent-free tenancy for services rendered. Further, mutawallis only get paid around Rs 8,000 per month and do not come under anti-corruption audits.

“The mutawalli system should be ended,” Khan said.

Robin Agarwal, 35, a member of the Sonipat Waqf Tenants’ Association, said his family has been residing on waqf property since 1947. They have undertaken construction and development work on waqf properties since then and pay rent only every 2-3 years.

“We always pay more than a fixed rent. The person who collects the rent keeps the extra money and it goes to his pocket,” Agarwal alleged. “That’s how they do corruption.” He also complained about arbitrary rent hikes and arm-twisting from waqf members.

Beyond corruption, vacant positions on waqf boards in Delhi, Uttarakhand, and Madhya Pradesh are causing a logjam, Jamaat-e-Islami’s Inam-ur-Rahman said. Decisions on using and generating revenue from waqf properties are stalled, preventing them from fulfilling their charitable purpose of helping disadvantaged Muslims.

Nearly two decades ago, the 2006 Sachar Committee report revealed that waqf boards possess land worth Rs 1.2 lakh crore, which could generate Rs 12,000 crore annually for the upliftment of the Muslim community. Instead, due to mismanagement and encroachments, they managed only Rs 163 crore.

The report recommended overhauling the boards, creating a dedicated cadre of officers, and improving property monitoring. However, these suggestions were never implemented.

Meanwhile, allegations of illegal waqf land sales keep surfacing every now and then.

In 2017, for instance, the Maharashtra land department suspended former waqf board chairperson Naseem Banu Patel for allegedly misusing her powers to declare waqf land as non-waqf land for sale to a developer.

In Karnataka, a 2012 state minorities commission report alleged that waqf property worth Rs 2 lakh crore was illegally transferred with the collusion of waqf board members, Congress leaders, and other officials since 2001. This report, tabled in the Karnataka assembly in 2020, was dismissed by Congress as “politically motivated”.

Surveys for property protection

With their anxieties about encroachment growing, waqf boards and other Muslim organisations are turning their attention to surveys as a tool to regain control over land.

A comprehensive waqf survey acts like a detailed inventory, showing the number of auqaf (individual properties) in a state, their nature and purpose, and the income they generate. It also documents land revenue and taxes for each property. Such surveys are conducted under the supervision of waqf survey commissioners.

However, the last time such a survey was conducted nationwide was in 1970, according to Jamaat-e-Islami’s Rahman. Though the Waqf Amendment Act 2013 includes a provision mandating surveys every ten years, a 2014 attempt was left unfinished because of limited budgets and a shortage of appointed survey commissioners in several states.

No further attempts were made until April this year, when the Haryana Waqf Board launched a new survey, with the goal to gazette properties that were not recorded in 1970.

A seven-member team has been scrutinising land records and has claimed to have already discovered 200 new properties in Yamunanagar city. These properties can now be registered and used for social welfare or generate income through renting, said Khan of the Haryana Waqf Board.

“Completing the survey will benefit properties that have not been gazetted yet by establishing the ownership rights of the waqf,” Rahman added.

ThePrint tried to contact Gurugram Division Commissioner Ramesh Chand Bidhan via email and multiple phone calls but has not yet received a response; this report will be updated if upon receiving one. A senior ASI official contacted for comment declined to speak, saying it was not within his purview to discuss the matter.

The need of the hour, said advocate Fuzail Ahmad Ayyubi, was to rein in mutawallis and sensitise the community at large that waqf property was not to be used for “personal interest”.

‘Missing’ CWC

A cornerstone of the waqf architecture is the Central Waqf Council (CWC), a statutory body established in 1964 under the Ministry of Minority Affairs. This body is supposed to maintain oversight and serve as a bridge between the government and the waqf boards—at least in theory, since it has been largely inactive for nearly a year and a half.

Facing an existential crisis, Delhi Waqf Board officials are desperately waiting for the CWC’s revival. They say reforms instituted through the CWC, which also advises the government on waqf matters, are crucial to improving the waqf system and repairing its damaged reputation.

This country is supposed to be run by the Constitution. (The Waqf) law is unconstitutional, illogical. The people of the waqf board have created havoc across the country. We want this law to be abolished

-Harnath Singh Yadav, BJP Rajya Sabha MP

“There is no one to inquire about the waqf boards or know about their well-being,” said the senior Delhi Waqf Board official.

Khan from the Haryana Waqf Board added that the boards are following regulations from 1966, which have become ineffective. Without a functioning CWC, formulating new regulations is impossible.

“Coordination has come to a complete standstill. We used to approach CWC for any problem but now we are not able to do anything,” he added.

In response to a question from Rajya Sabha MP Javed Ali Khan last July, the Ministry of Minority Affairs said that the constitution of the CWC was “currently ongoing”.

The ministry also noted that the central government had used its authority under the Waqf Act to shorten the term of the CWC from five to three years in 2014. Following this change, it said nine members were appointed in February 2019. Seven of these members were then re-appointed for just a one-year term from February 2022 to February 2023.

Since then, no new members have been appointed.

Also Read: RWAs are waging a war against Muslims—within societies, on WhatsApp groups

Reform vs repeal

With the BJP MP’s bill to repeal the Waqf Act, the Delhi demolitions, and the PM’s high-octane speeches, there widespread fear among Muslims that the Modi government’s third term could spell the end of the waqf system.

Despite frustrations with the waqf boards’ inefficiencies and corruption, many Muslims favour reform over abolition. For them, waqf boards play a crucial role in maintaining religious sites and providing social welfare services through schools, hospitals, and other charitable endeavours.

The need of the hour, said advocate Fuzail Ahmad Ayyubi, was to rein in mutawallis and sensitise the community at large that waqf property was not to be used for “personal interest”.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a former member of the CWC also called for reforms, but emphasised that the waqf system was in no danger from the Modi government.

“The Modi government takes the issue of Waqf very seriously. It’s not true that Modi will abolish it,” she said.

The senior Delhi Waqf Board official was also confident about the Waqf Act’s immediate safety, citing the logistical burden that managing all properties would put on the government.

“We don’t think the Waqf Board will be abolished—what will happen to so much property? Who will manage it? The government will also think about it,” he said with a faint smile.

He then opened a capacious brown file, eager to get back to work. It’s been 12-hour workdays, seven days a week, due to the staff crunch. “This Waqf Board office has become my home now,” he said.

Meanwhile, on a mid-May evening, worry creased the forehead of Jamaat-e-Islami’s Inam-ur-Rahman as he watched a WhatsApp video. It featured Ajay Pratap Singh, an Agra-based lawyer, who had just set off another ‘mandir-masjid’ dispute with a lawsuit against the UP Sunni Central Waqf Board. This time, the claim is that the 15th-century Atala Mosque in Jaunpur was originally a Mata Mandir.

“We will fight a legal battle to save every mosque,” he said. “If we concede defeat in one, we will lose all.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

A well written article! I think that the Hindu nationalists may be exaggerating when they say that waqf boards can lay claim to any land they desire; however, a law that makes all such land permanently waqf, and thus ostensibly to be put to use primarily in furthering the interests of one community, does seem unfair if the boards own a lot of land. To promote integration, a better approach would be if the waqf board conspicuously strives for helping society (all religions) and doesn’t claim new land. Langars in the Sikh tradition are a good example of how such help translates to goodwill. In our country which has so much historical conflict of religions, religious bodies need to be seen as a net good for harmony of society to be protected.