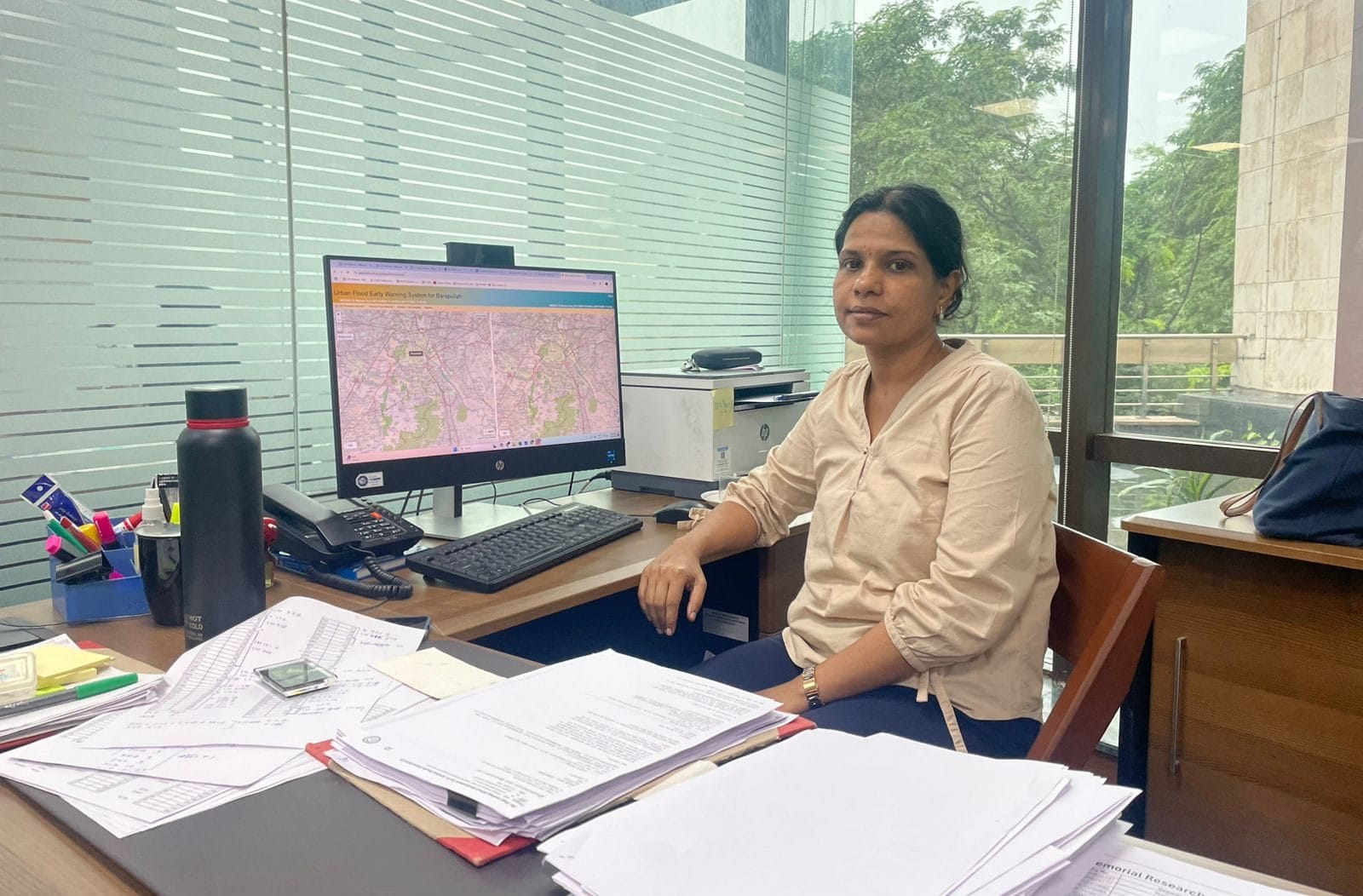

New Delhi: A street map of Delhi is sprawled across a computer monitor at professor Dhanya CT’s office at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. There are no red lines highlighting traffic jams or pins marking metro stations. Instead, multi-coloured dots glow on the screen. It’s an urban flood early warning system, developed at India’s premier technology institute, that can one day save Delhiites from traffic snarls in the rainy season and provide critical data to authorities managing waterlogging.

“We used the stormwater drainage network of Delhi to develop this system. As the rain advances, you will see coloured dots appear at different junctions,” said Dhanya, pointing to a blue dot at Green Park Extension, signifying a flood depth of between one and two metres. The system was piloted in the Barapullah basin, located on the western bank of the Yamuna River and encompassing Central and South Delhi. Lajpat Nagar, Defence Colony, Minto Bridge, and Sarita Vihar—all located in the basin—are prone to flooding every year.

With monsoons wreaking havoc on Indian cities and even posh pockets routinely submerged, local bodies are turning to research-focused academic institutions and startups for technology solutions to map, predict, and mitigate urban flooding. From real-time flood alerts to drone-based waterlogging surveillance, a slew of initiatives is being tested in Delhi, Bengaluru, and Kanpur.

In South Indian cities, drones have already taken to the sky for flood assessments. Bengaluru-based Skylark Drones, which provides drone-based services and software across sectors such as mining and renewable energy, has partnered with the government of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh for urban flooding projects in Bengaluru and Vijayawada, respectively.

“Earlier, mapping was done using satellite data or field surveys,” said Sucharitha R, Manager of Geospatial Solutions at Skylark Drones. “But now, governments are realising the scope of drone data and high-resolution images for their areas of interest.”

In April 2025, the Central Water Commission (CWC), part of the Ministry of Jal Shakti, signed an MoU with IIT Delhi to leverage technology for water resources management. As part of the agreement, the two organisations would collaborate on flood management using technology, hydro-informatic tools, water quality analysis, and river basin and irrigation management.

“Water is a multidisciplinary sector that requires collaborative efforts among all key stakeholders,” said Dr Mukesh Kumar Sinha, Chairman, CWC at the MoU signing. “This collaboration will open new avenues for innovation, with IIT students engaging in real-world challenges through internships and live projects while CWC benefits from IIT Delhi’s research outcomes.”

Drones to the rescue

In September 2022, images of Bengaluru’s Epsilon Residential Villas went viral—not for their multi-crore price tag, but for Bentleys and BMWs submerged in floodwater. As torrential monsoon rains inundated the compound, residents were evacuated on boats and tractors, a stark indictment of the country’s technology capital. Skylark Drones is hoping to fix the city’s flooding problem once and for all.

Founded in 2015, the Bengaluru-based company has partnered with the government to conduct a flood assessment of the city, starting off with a drone survey. But it isn’t as simple as launching a wedding drone in the sky and taking photos. Skylark’s drones capture detailed, street-level images and combine this with third-party data.

“First, we get high-resolution spatial data with centimetre-level accuracy—so we can count the number of cars, the girth of the tree,” said Sucharitha, explaining that these images capture precise elevation changes and water flow patterns. “We then combine this with existing information like stormwater drain networks, soil condition, and IMD (India Meteorological Department)’s 50 years’ historical rainfall data.”

After the data is fed to a model, low-lying and flood-prone areas are identified. If waterlogging plagues a particular locality, urban local bodies can plan mitigation strategies, which can range from adding more drains and water retention ponds to rejuvenating lakes. But the most critical output of the modelling is flood depth and velocity maps for different intensities of rainfall.

“By understanding how deep the flood waters are and the speed at which they move, it helps authorities calculate how much time they have for mitigation strategies,” she said, adding that the data allows them to assess the risk of a particular building or zoom out to entire areas.

Skylark identified two critical areas based on their surveys: Nagawara (near Manyata Tech Park) and HSR Layout, highly urbanised areas home to the city’s IT companies and startups. The analysis pinpointed several contributors to flooding in the region, including clogged stormwater drainage, encroachments on natural drains, and a lack of retention and detention systems to buffer peak runoff.

But Skylark can only provide recommendations. It’s now up to the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) and Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) to take action.

Before drones entered the mainstream, satellites were the primary tools for mapping. But when it comes to assessing urban flooding, satellites fall short. The images lack the clarity and resolution needed for detailed ground-level analysis.

“Satellites cannot penetrate the cloud cover in the sky, especially during the monsoon season,” said professor Rajiv Sinha, founder of TerrAqua UAV, a geospatial intelligence startup incubated at IIT Kanpur. “Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites can penetrate through clouds and give a signature of water, but these are of low resolution.”

According to Sinha, satellites also have long repeat cycles—the time it takes for a satellite to pass over a particular point on the Earth’s surface. Additionally, the images do not provide any information on the depth of the flood. Both short repeat cycles and depth perception are critical data points to understand flooding.

Sinha’s team at TerrAqua UAV flew their drone over 3,700 hectares of land around Kanpur, covering villages on either side of the Ganga, collecting high-resolution images and building a flood inundation model. “This kind of model can be connected to the water level data that is being measured at various locations across the river, which can then simulate the resulting inundations better and earlier,” he added.

While TerraAqua UAV’s eight-month pilot project is over, it received interest from both the water resources department and the municipal commissioner for expansion, according to Sinha. But funding large-scale drone operations is expensive, and covering larger areas requires specialised aeroplanes. For now, Sinha is satisfied going district by district.

“We are not money-oriented, looking to make billions of dollars,” said Sinha, who has been an academic researcher for the last 30 years. “And we are not asking organisations to wait another ten years for the technology. We are already giving them this solution—they just need to step up and implement it.”

Also read: Indian railway stations are failing women. Dark corners, broken CCTVs, loitering men, rape

Private players

The website of Skymet, a Noida-based weather forecasting organisation, is crowded with maps, blog posts, and data points—humidity, precipitation, wind, and rainfall distribution across the country. The company proactively issues flood alerts to the public, leveraging its over 6,000 Automatic Weather Stations (AWS).

“We provide daily alerts through our website, app, and YouTube channel,” said Mahesh Palawat, Vice President of Meteorology and Climate Change at Skymet. “With our lightning detectors that track the movement of thunderclouds, we can provide both short-range or medium-range forecasts.”

A growing ecosystem of private weather organisations is offering more granular, hyperlocal forecasts. With over 1.65 million subscribers on its YouTube channel, Skymet posts videos twice a day, alerting the public to sudden changes in weather, including the possibility of flooding in urban areas. Palawat highlighted that apart from their own weather stations, their models are infused with data from IMD, Doppler radar systems, and satellites.

Comments on the YouTube videos vary widely, with some users asking if the rains will arrive in drought-prone areas while others plead for alerts on rainfall ceasing. The anchors in the videos are the new weather gods, bringing relief or pain.

“A person can see in which direction the weather system is moving, which states or districts will get heavy rainfall,” said Palawat. He added that the majority of the viewers of Skymet’s Hindi videos are farmers from Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh, many of whom rely on the updates for flood alerts.

And while they have no active partnership with municipal bodies, they have clients in the private sector. Energy companies use Skymet’s data points for heavy rainfall and flooding to adjust power generation, based on an increase or decrease in demand from different areas.

Also read: Bengaluru billionaires are changing Indian philanthropy. Old-style CSR is out

Refinements, AI integration

Last year’s monsoon season was harsh on the IIT Delhi campus. Heavy rains caused runoffs and inundations, a situation the institute was not fully prepared for. The incident set Dhanya CT and her team in motion, furthering their resolve in the early warning system they were developing, part of a much larger research project on water security in the National Capital Region.

“It poured for only two or three hours, but in that period, for one hour, the rain came down heavily and created a runoff,” said Dhanya, recalling the destruction of labs that were located downstream. “The inundation was 1.52 meters and stayed in the labs for days, damaging research and evidence that had been collected over decades.”

A multi-tier drainage plan was drawn up, from making basic improvements to identifying and correcting building construction over natural drains. Dhanya and her team also recommended that the IIT Delhi administration incorporate green roofs, permeable pavements and a focus on gravity-based drainage, since water pumps can be unreliable.

By visiting every nook and corner of campus, data was gathered at a granular scale—a micro-level testing ground for a much larger, five-year project under the institute’s Water Security and Sustainable Development Hub. Kicked off in February 2019, the project aimed to ‘enhance water security’ in the nation’s capital in collaboration with four countries—Colombia, Malaysia, Ethiopia and India. It was funded by the United Kingdom Research and Innovation’s Global Challenges Research Fund.

“We had a good grip of our campus, but not of the Barapullah basin—the next level of the project,” said Dhanya. The basin is the drainage catchment area in South and Central Delhi that encompasses large parts of the city’s natural stormwater flow systems. “In 2015, our undergraduate students went onto the field and corrected the existing drainage maps of the sub-basin.”

This was all done as part of a separate project assigned to IIT Delhi by then Chief Minister Sheila Dikshit to make Delhi’s master drainage plan, last prepared in 1976. The students revised the map by marking inlets, outlets, and operational manholes. They created an updated drainage network, which was used as the base for the flood warning system. Rainfall predictions from IMD were imported into the team’s model and cross-referenced with the drainage networks in the map, highlighting flooding choke points across the city.

Ultimately, the model was a trial run to showcase how an early warning system would function. When research on the project was undertaken in 2024, the warning system highlighted spots across Delhi that experienced varying levels of flood inundation: Pandara Road, Maharishi Raman Marg, Prime Chowk, and RK Puram.

But the model wasn’t yet ready for a public rollout.

“It’s a very crude model, but at the experimental level, it is ready,” said Dhanya, admitting that refinements were needed to check the accuracy of the output. “All I have is data given by the traffic police, who tell me which junction is flooded and whether there was a traffic jam. To validate the model, I need the spread and depth of the flooding.”

To solve the problem of a lack of data, the team turned to the next best alternative—Delhi’s citizens. A mobile application, Aab Prahari (flood watch), was launched in 2022 to collect geo-tagged information on flooded areas reported by citizens. By uploading pictures and gauging the depth of the water (guided by instructions on the app), commuters could identify and avoid areas that were inundated. But the app didn’t gain much traction.

“We got a good amount of data when the app was launched, but since its use case is only during the monsoon season, it was difficult to consistently get citizens to use it,” said Dhanya, adding that the institution does keep promoting the app every season.

The water security project concluded in 2024, but the early warning system is continuing to be refined in collaboration with other IITs. The last data point in the system is logged on 17 January 2025, but behind the scenes, Dhanya’s PhD students are still working across rainfall prediction, model refinement, and the integration of AI and machine learning for faster simulations. And with the recent MoU with the Central Water Commission, government bodies are now understanding the value her team brings to the table.

Udit Hinduja is an alumnus of ThePrint School of Journalism.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)