Barnala: A group of turbaned and ageing men huddle across a large table, hunched over their phones, watching a video of a young man’s lynching. It’s a sweltering Sunday afternoon in Punjab, in the Barnala zonal office of the Tarksheel or ‘Rationalist’ Society. A small group of its executive and organisational members have gathered here on a weekend, just a day after the lynching of a 19-year-old man accused of sacrilege, or beadbi, in Ferozepur district.

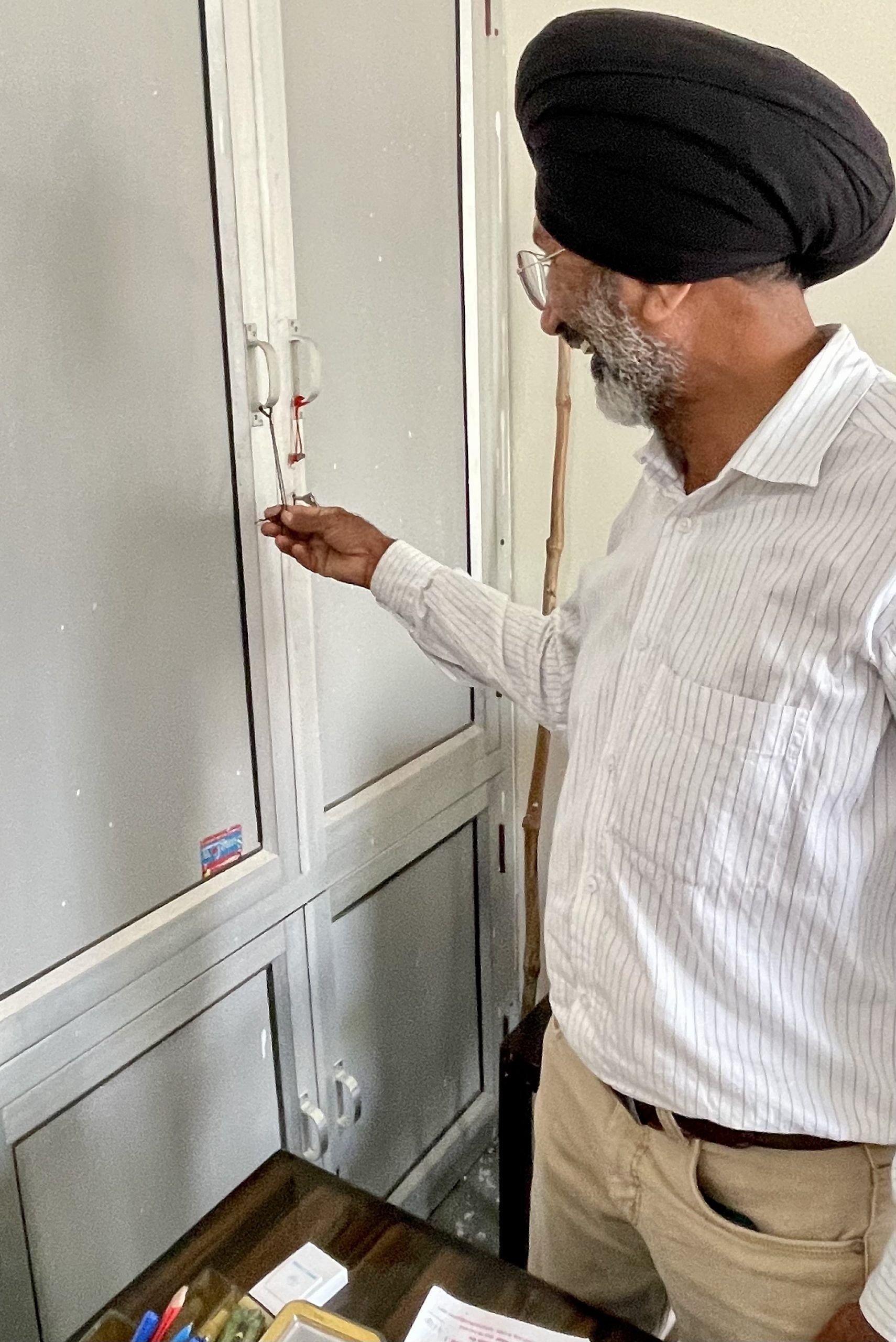

Rajinder Bhadaur is the main organiser of the rationalists in the area. But he is still powerless.

“There is so much terror that even the victims’ families do not wish to pursue these cases,” he says. But there’s not much he and his band of atheists and rationalists can do as Punjab is riven with religious tension over beadbi lynchings.

“We don’t agree with such killings, but we also don’t have the resources and safety to get involved in tackling this head-on. When people see us as atheist, as nastik, they don’t even wish to take our help anyway,” adds the 64-year-old Bhadaur.

Prominent religious bodies such as the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) have emphasised “justice” against sacrilege as opposed to the killings. But Giani Raghbir Singh, the Jathedar (head) of the Akal Takht, the highest temporal authority of the Sikhs, tweeted requesting the Sikh sangat (community) to socially and religiously boycott the family of the lynched youth, Bakshish Singh. Raghbir Singh even urged the public to prevent the man’s last rites from being held in a gurdwara.

It is safer, and financially more viable given our resources, to spread awareness on scientific thinking and against superstition. Doing advocacy-work and supporting families in beadbi cases or against deras (religious organisations) is quite unsafe. We have families, people can become very hostile and there is a threat to life – Rajinder Bhadaur, Tarksheel Society

Kuldeep Singh, 32, one of the few youths present at the rationalists’ Sunday meeting, compared this treatment to that of ‘outcastes’.

“There is a lot of terror in the families; they don’t even wish to be identified publicly. Even gurdwaras don’t entertain them,” he says.

According to Tarksheel’s Rajinder Bhadaur, Padma Shri awardee Nirmal Singh Khalsa, who succumbed to Covid-19 in 2020, was also denied cremation spaces in Punjab. Khalsa belonged to the Mazhabi (Dalit) Sikh community, and was a hazoori ragi (kirtan performer) at the Golden Temple in Amritsar. His last rites were reportedly performed on an unkempt piece of land.

However, stakes are “at a different level” when it comes to the sacrilege-accused, he says. Those who “anoint themselves dharam ke thekedar (custodians of religion) pass orders that lead to fear and ostracism,” he adds.

“It is hard to identify as an atheist even now, especially if you are in the hinterlands. We call ourselves tarksheel (rationalists) so as to not alienate people. Every atheist is a rationalist, but being a rationalist does not make you an atheist,” rues Rajinder Bhadaur.

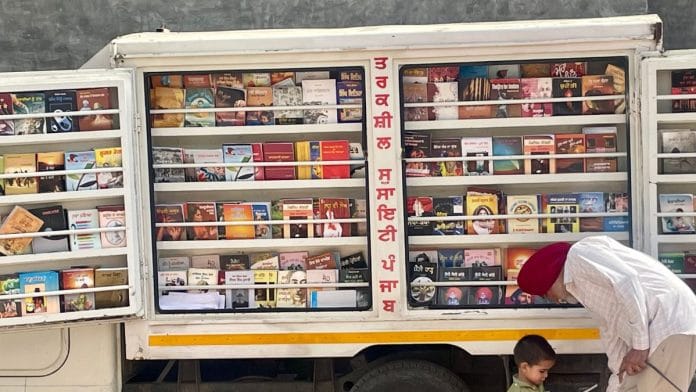

Groups like the Tarksheel find it relatively easier to organise mobile book vans, workshops in schools, and other public events to inculcate scientific thinking. It’s a less mammoth task than confronting religious fundamentalism and supporting the families of those accused of – and punished for – sacrilege.

“It is safer, and financially more viable given our resources, to spread awareness on scientific thinking and against superstition. Doing advocacy-work and supporting families in beadbi cases or against deras (religious organisations) is quite unsafe. We have families, people can become very hostile and there is a threat to life,” says Bhadaur.

Roots of the Tarksheel Society

Megh Raj Mitter and Sarjit Talwar founded the Tarksheel Society in 1984 – when Punjab’s air was thick with militancy and religious fundamentalism. They were influenced by the book Begone Godmen, written by rationalist activist Abraham Kovoor.

Headquartered in Barnala, the society today has units in 10 ‘zones’ across Punjab. These units work to propagate scientific and rational approaches through school workshops, health clinics and ‘public challenges’ to self-styled spiritual leaders and miracle workers.

Rajpal Singh, an executive member of the group, claims that it has over 1,000 active members, and that over 12,000 people subscribe to its Hindi and Punjabi magazine named Tarksheel Path.

As religious conservatism grows – particularly among Hindus and Sikhs in Punjab – groups and individuals like the Tarksheel Society find increased footing.

Those not affiliated with any religion are but a speck in India’s 1.4 billion populace. This group includes atheists and agnostics, rationalists, the undefined, the culturally religious but non-practising, and the non-religious but spiritual.

Despite the lack of mass awareness, these numbers may be growing. According to the 2001 Census, only 0.7 million or 7 lakh persons recorded themselves under the “religion not stated” category. But by 2011, this figure jumped to 2.9 million or 29 lakh.

However, they also find themselves at a crossroads.

“In 1986, two rationalists affiliated with the Tarksheel group were murdered by Khalistani militants. Recently, in the Ram Rahim case, two of our members – Rajaram Handiyaya and Balwant Singh – testified as witnesses against the man and his dera. But they’ve faced threats to their lives,” Bhadaur says, emphasising his acquaintance with the journalist Ram Chander Chhatrapati. Chhatrapati was shot dead after he reported on the rape allegations against Dera Sacha Sauda chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh.

It is hard to identify as an atheist even now, especially if you are in the hinterlands. We call ourselves tarksheel (rationalists) so as to not alienate people. Every atheist is a rationalist, but being a rationalist does not make you an atheist – Rajinder Bhadaur.

Punjab’s rationalists aren’t alone. Across India, atheists and rationalists working against the grain face serious threats to their lives. In 2013, anti-superstition activist Narendra Dabholkar was shot to death in Pune. Members of his organisation, Maharashtra Andhshraddha Nirmoolan Samiti (MANS), continue to face threats for the work they do.

Then, there are regional atheists and prominent rationalists like Govind Pansare, Gauri Lankesh, and MM Kalburgi who have all been killed in the past decade. There’s also author and Rationalist International founder-editor Sanal Edamaruku, who was forced to live in exile in Finland after being accused of blasphemy.

Indian atheists battle their families, relatives, neighbours and community shrines as well as land in court for certificates. For most, it is often a tricky shaky trapeze walk between culture and religion.

Also read: In Ajmer maulana killing, children got the better of cops. Spotlight now on madrasa safety

Fighting ‘parivaar’, ‘parampara’, and beyond

Identification isn’t an easy ask, and the chirpy, keen-eyed Sarabjeet Kaur is a case in point. A resident of Wander Jatana village in Punjab’s Faridkot district, Kaur is like any ordinary middle-aged woman, making her way through life with an upbeat lilt. But she’s also a member of the Tarksheel Society and has ‘converted’ her husband and two children into rationalists – much to the chagrin of her older brother and neighbours.

It all began in 2010, when Kaur’s father died due to a heart attack following a depression-fuelled suicide attempt. His death put Kaur’s mind in tumult.

“After my father’s death, and knowing at the back of my head how he was depressed, everything about me changed. I constantly started overthinking and living in paralysing fear. If anyone felt even slightly sick, I’d think they would die and I would also get that and die. If some neighbour’s child fell sick, I would think that my own children would develop the disease and die,” recalls the 42-year-old, who was on psychiatric medication for a good six years. But things changed when another resident gave her husband a referral to the weekend clinic run by the rationalist Tarksheel Society.

The clinic is a three-room non-descript structure, located on the side of a main road in Bargari town. It has a big central room with posters and paintings of Bhagat Singh and quotes on nature and scientific phenomena. The other two rooms are bright and airy, with desks, chairs and a single bed each. Kaur points to one bed and reminisces about when she spent her weekends there. Little did she know that she would devote close to two years of her life to this makeshift clinic, watching her belief system change entirely.

The clinic is headed by Dr Channan Wander, a veterinary specialist by his own admission. Wander, who also practices hypnotherapy, has been running the space since 2002, and claims to have helped treat “unscientific beliefs” and “bhoot-pret ki kalpana (concept of ghosts and spirits)” since the 1980s. He says that even today, people – particularly from the rural interiors of Punjab – attribute depression and anxiety to spirits or an “irrational” unknown. The clinic is frequented by seven to 10 people every weekend.

“I started coming here on Saturdays, and they made me lie down and focus on a dot, which altered my consciousness. I’d then be told to keep meditating and tell myself that nothing was going to happen to me,” Kaur tells ThePrint. They made her realise that her father’s death was no omen or sign. It was what it was – a heart attack. She says that this thought was drilled into her head somehow, and she has been off medication since.

Kaur’s experience at the clinic also reduced her faith in and reliance on religion. Gradually, her husband and two children, aged 17 and 14, stopped visiting their local gurdwara and organising paath (reading of Sikh texts) at home. Of course, this had repercussions for Kaur and her family. She now barely talks to her brother and keeps her family’s beliefs private when forced to participate in festivals back in the village.

“I don’t know whether to define myself as an atheist. I do believe in the teachings of our gurus, but I no longer believe in superstitions, or in going to a gurdwara and asking God for things. Those who believe in god keep insisting on kismat (destiny). But now I and my family all believe in doing good deeds and hard work. There is no kismat and karma.”

Also read: How Punjab farmers sacrificed high income for a big cause—they gave up Pusa-44 this year

The non-religious soldier on

Popular perceptions of atheism and the non-religious are affixed to caricatures of upper-class, urban youth, deep in the trenches of Reddit and influenced by theorists like Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins. But there’s a less visible spread of this thinking – away from public attention and across India’s villages and smaller towns.

According to the 2011 Census, more rural than urban-dwelling people identified as ‘religion not stated’ or ‘non-religious’.

Often, these people have no protection and deliberately fly under the radar. They’re quite active on Facebook in Hindi and other regional language pages and groups. Mission Nastik Bharat (Mission Atheist India), a private Hindi Facebook group, has over 1,33,000 members, with an ‘About’ section that emphasises anti-casteism and questions ‘Manuvadi’ superstitions. There are countless others such as ‘Main Nastik Kyun Hu (Why I am an atheist)’, ‘Tarksheel Nastik’ (Radical Atheist), and more, with followers and members running upwards of 40-50,000. There’s frequent sharing of videos, posts and memes parodying godmen or religious superstitions, and occasional invocations of Buddhism, Ambedkar and more.

I don’t know whether to define myself as an atheist. I do believe in the teachings of our gurus, but I no longer believe in superstitions, or in going to a gurdwara and asking God for things. Those who believe in god keep insisting on kismat (destiny). But now I and my family all believe in doing good deeds and hard work. There is no kismat and karma – Sarabjeet Kaur, 42

And many across the country are acting and voting against religion and superstitions. All while enduring mini-struggles in their families and neighbourhoods.

Also read:

Battling everyday hurdles

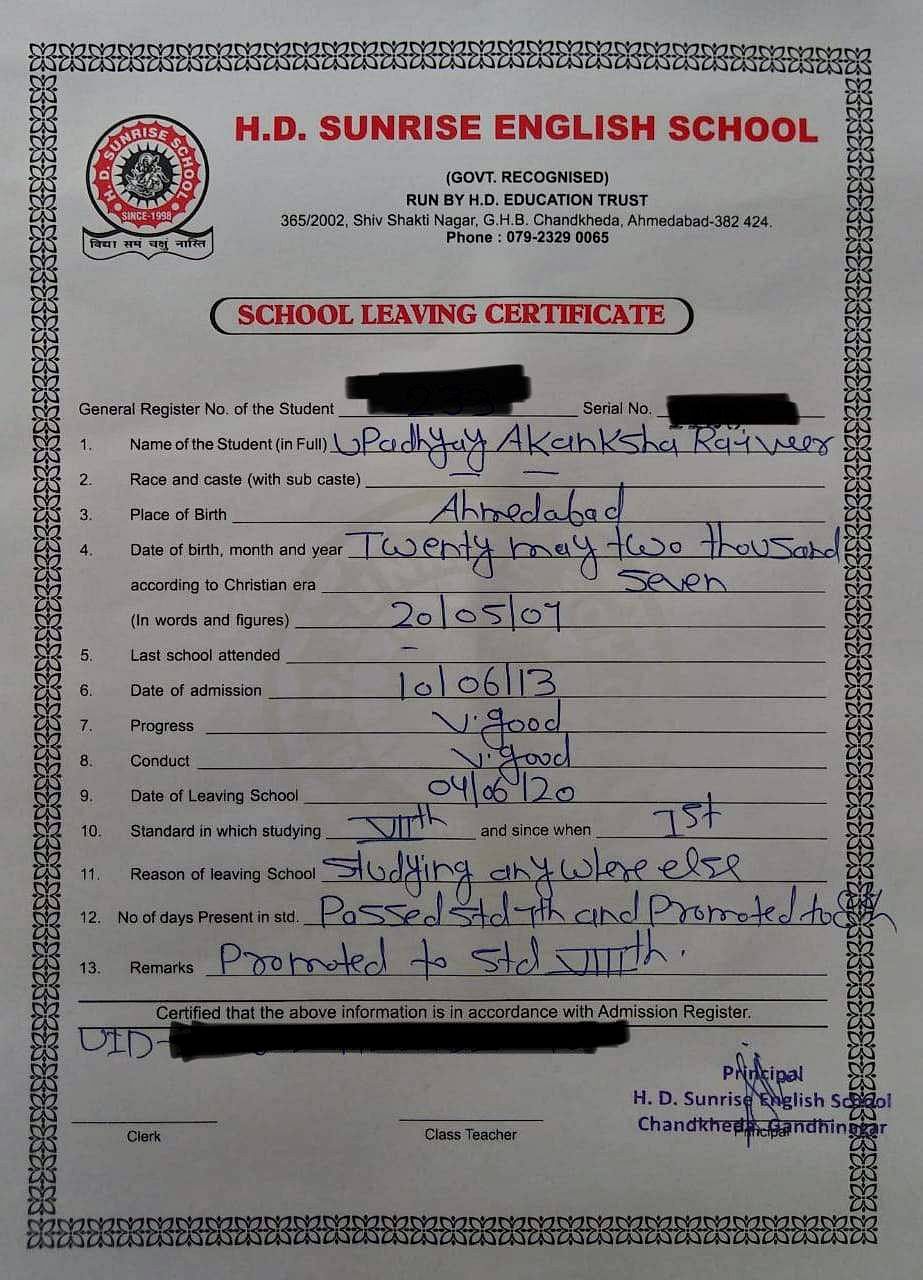

For Ahmedabad-based Rajveer (who once went by Rajveer Upadhyay), these battles were never a conscious choice; they were always a compulsion.

The auto-rickshaw driver-turned-social worker has spent the last seven years running from pillar to post. He hopes to declare his atheism with a notarised certificate from a magistrate or district authority, and even has a petition pending in the Gujarat High Court.

The law doesn’t require it, but Rajveer asserts that he wishes to not be associated with any religion or caste. It has a lot to do with his family’s Dalit origins.

“I belong to the Scheduled Caste community of ‘Garuda Brahmins’. I know the discrimination we’ve faced because of this, especially here in my state. But what really made me question things was seeing the Patidar movement for reservation. How can a privileged group like them demand reservation whereas people like us continue to suffer discrimination?” says Rajveer. That’s when he realised these identifications were not helping him. He wanted to disassociate entirely from defining himself on religious and caste lines.

This disillusionment with the caste system made Rajveer want to forego reservation benefits for himself and his daughters. He even dropped his Upadhyay surname from his Aadhaar card, which he initially thought would help someone from an oppressed background like his.

The real struggle began when he tried to obtain official certification for his beliefs (or lack thereof). In 2018, Rajveer petitioned the high court seeking a declaration of his beliefs under the Gujarat Freedom of Religion Act of 2003, a law pertaining to religious conversions.

“There is no legal status accorded to the atheist category of persons in this country. So, I decided to use an existing law of my state to announce my ‘conversion’ to atheism. But this law also has a provision that allows for any blood relative or aggrieved party to file a police complaint if a person chooses another religion or belief system. So, I challenged this legislation too. The case is still pending,” he says.

The former auto-driver went on to add how his battle was inspired by lawyer-activist Sneha Parthibaraja of Tamil Nadu. In 2019, Sneha successfully persuaded her state’s authorities to legally declare her as belonging to ‘no religion, no caste’.

“My parents are both lawyers, they are Leftists and rationalists and belong to different castes. Even me and my siblings’ names are of secular or mixed religious roots,” she says. Her name is an homage to Emergency-era political prisoner and actor Snehalatha, who died in custody.

Sneha’s sisters are called Mumtaj Suriya and Jennifer, while her daughters are named Aadhirai Nasreen, Aadhila Irene and Aarifa Jessy.

I belong to the Scheduled Caste community of ‘Garuda Brahmins’. I know the discrimination we’ve faced because of this, especially here in my state. But what really made me question things was seeing the Patidar movement for reservation. How can a privileged group like them demand reservation whereas people like us continue to suffer discrimination?

– Rajveer, Ahmedabad

Also read: Punjab’s most hated—sacrilege accused live in hiding, face death, can’t use phones

Fighting for recognition

People like Rajveer and Sneha, who approach courts for the sake of their identity, are exceptions to the norm. While nothing bars anyone from renouncing their religion in India, the country as yet doesn’t officially recognise categories such as atheism, agnosticism or non-religious.

The 2001 and 2011 censuses used the ambiguous “religion not stated” category. They also featured an ‘other religions and persuasions’ category, with nearly 82 different faiths and sects. In government forms and applications, the category of ‘Others’ or ‘Any Other’ is usually the only option available. The logistical hurdles for most non-religious people remain immense, given this absence of categories and a lack of encouragement for the same from government officials and society at large.

It’s also common for many to state their family or paternal religion instead of their own beliefs, owing to the stigma around being non-religious. One such discussion on Reddit captures it best. Here, users discuss how “Dad still marks me as a Hindu” and how in every form there is “no option but to choose the religion of my parents”. It’s evident how stigmas faced by family and society play a big role in this undercounting.

Kaur and her family now find themselves ostracised for not partaking in practices like lassi chadhaana (offering buttermilk to any stone or rock seen as spiritually significant) in her village. Rajveer, on the other hand, saw the end of his marriage, apart from a struggle with jobs.

Rajveer, who only became an atheist in his 20s, has now married a second time. The first fell apart, “because she did not see eye-to-eye with me on my activism and beliefs”. His second wife, too, is religious, but the two have been actively working toward mutual understanding.

“It is very, very difficult for an atheist to fully live like one in our society. I still have to participate in religious festivals even if I don’t pray. If an atheist gives up on all this in our society, he would become so alienated and lonely that he’d be driven to suicide,” he adds tersely.

Despite Rajveer’s attempts to distance himself from his caste identity, the allusions made to it in professional settings worsened the problem. Rajveer holds a bachelors degree in sociology and attempted to do a masters in psychology before dropping out. Working as an auto-driver when no other opportunities were available, he later quit and tried applying for white-collar jobs again.

“I even managed to secure a job as a supervisor with an education-based company. But they used to do pooja-paath in office. I constantly felt scrutinised for not being an enthusiastic participant,” says Rajveer. After a point, he used his Upadhyay surname to pass off as a Brahmin.

His work contract is now expiring and will not be renewed. The 40-year-old still struggles to answer questions about his background in interviews.

Also Read: Lynching to shooting, ‘instant justice’ is on the rise in Punjab’s sacrilege cases

Marrying as a non-religious person

Marriage and intrusive questions around death are also battles that many atheists brave. Marriage in India is largely embedded with religious personal laws. ‘Secular’ legislation such as the Special Marriage Act of 1954 is a whole new obstacle course. The SMA permits people with no religious beliefs to marry, apart from couples belonging to different religions, castes and social backgrounds. However, the legislation mandates a notice period of 30 days, along with public displays of personal details and addresses. This allows vigilantes and family members to object to such unions.

Everyone here in these parts views things like the SMA or court marriage as solely for eloping couples. There are so many hurdles to it that nobody here sees it as a normal thing. It’s an aberration even for us non-religious people – Rajinder Bhadaur, Tarksheel Society

Attempts at legislation such as a Uniform Civil Code in Uttarakhand have largely proved to be a replication of largely Hindu personal laws and far from being secular.

“Everyone here in these parts views things like the SMA or court marriage as solely for eloping couples. There are so many hurdles to it that nobody here sees it as a normal thing. It’s an aberration even for us non-religious people,” says Tarksheel Society’s Rajinder Dhanaur.

Dhanaur, as well as many of his zone’s comrades, opted for marriages without ‘laava phere’ or other Sikh wedding rituals. In fact, Dhanaur and the others evaded religious personal laws altogether by never registering their marriages. It helped them escape the baggage of religious tags.

“A marriage certificate is only needed if I have to go abroad or for very specific tasks. Otherwise, we just get joint bank accounts made or declare ourselves husband and wife on Aadhaar and other identification documents. Almost all of us just exchange rings in the presence of friends and family, that’s it! It hasn’t been a problem so far,” says Mohali-based Satnam Singh Daun, who is also associated with the Tarksheel Society.

Resisting casteism

An anti-corruption activist, Daun fought a harrowing court battle for his teenage son’s caste certificate to be made without any mention of religion. The 47-year-old atheist recently secured an order from the Punjab and Haryana High Court for this.

If I had not gone to the high court, maybe nobody would even have asked why computerised forms do not have the ‘Others’ drop-down option anymore. But we can’t achieve what we want without any struggle – Satnam Singh Daun, Tarksheel Society

Religion and reservation are intertwined in public discourse. A big issue in social justice is that Scheduled Caste reservation has only been extended to Hindu, Sikh and Buddhist-identifying Dalits. It has been denied to Dalit Christians and Muslims. Reservation for someone without religious identification, thus, reveals a whole new gamut of challenges.

Daun points out how, owing to his beliefs and social stigma, he initially didn’t wish to obtain a caste certificate. However, his financial difficulties forced him to seek proof of his economic marginalisation. “Especially because my son was trying out for national-level shooting without much resources, and the quota would’ve helped him.”

In 2022, Daun approached the deputy commissioner in Mohali to get a caste certificate. Except he realised that there was no ‘others’ category under religion anymore.

“The authorities just told us that the computer has no drop-down options like the ‘others’ category anymore. I was shocked, because I’d remembered this always existed if you didn’t wish to identify with any religion. Then they told me my son couldn’t claim the caste background if he didn’t claim to be Hindu or Sikh or any of the religions,” recalls Daun. He found that absurd, considering “caste and material conditions are a real thing and independent of what I practise or not”.

Daun soon filed a petition and managed to obtain a court order in his favour. Today, he flashes the certificate as proof of the possibility that people can identify as OBC without stating their religion.

“If I had not gone to the high court, maybe nobody would even have asked why computerised forms do not have the ‘Others’ drop-down option anymore. But we can’t achieve what we want without any struggle,” he stresses. Daun and his wife are both non-religious and have named their children Tejas and Navchetna. As for their surnames, they prefer to use the name of their village, Daun.

Satnam Daun doesn’t see the need to use ‘Singh’ or ‘Kaur’ as suffixes for his children’s names, even though he himself proudly flaunts a turban. “You’ll find that many of us atheists in Tarksheel Society have turbans. That is just part of [our] culture. You can be non-religious and still have cultural markers.”

Also Read: Who were the men lynched for ‘sacrilege’ in Amritsar & Kapurthala? No clue yet, say police

Resisting majoritarianism, atheist style

Both atheism and a strand of Indian rationalism experienced some success with the rise of Dravidian and Communist parties in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The advancement of Buddhism, particularly through its role in the Ambedkarite movement against caste, raised questions about religious identity and the rejection of god.

However, things seem to have changed over the past two to three decades.

In 2021, when MK Stalin took oath as the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, he did what is likely to still come as a shock to most other Indians – solemnly swearing by his ‘conscience’, not god. His son Udhayanidhi Stalin, who identifies as an atheist, faced widespread criticism for speaking out against Sanatana Dharma. While he clarified that the position he took was against caste discrimination and majoritarianism, the damage was already done.

Earlier this year, Karnataka’s Chief Minister Siddaramaiah issued a public clarification that he “was not an atheist”. Meanwhile, Congress’ Northeast Delhi face Kanhaiya Kumar likened his struggle to the Hindu god Krishna (also known as Kanhaiya). It’s a far cry from his days as a non-religious student leader and Communist Party of India politician.

Even Opposition politicians and leaders seen as secular are grappling with the challenge of reconciling their non-religious beliefs with the political necessity of flaunting religious affiliations.

“When we are in politics, we cannot completely alienate ourselves from the aspirations, beliefs, fears and hopes of the society. Out of respect for the collective, an individual in politics does not and cannot impose his or her faith on the society,” says the Congress’s Pawan Khera.

Others such as Swaraj Abhiyan’s Yogendra Yadav say that technically, there are no barriers to being non-religious. But ground realities are, unfortunately, different.

“If a schoolteacher comes to your house and hears the name Yogendra, they automatically record it as Hindu. It’s only if you’re aware, or someone goes the extra mile to ask and be sensitive about it, then there’s this identification as atheist,” he says.

Despite being a “non-religious person from a Hindu background”, he has no qualms sharing and dealing with religious beliefs.

“On the contrary, I have utter contempt for the irreligious people like the RSS, who invoke religion for political ends, that is different from being deeply religious or spiritual in itself.”

As the public sphere becomes increasingly desecularised, groups like the Tarksheel Society and MANS, and people like Rajveer and Satnam Daun, find themselves battling for an alternative existence in social and political life.

If a schoolteacher comes to your house and hears the name Yogendra, they automatically record it as Hindu. It’s only if you’re aware, or someone goes the extra mile to ask and be sensitive about it, then there’s this identification as atheist – Yogendra Yadav, Swaraj Abhiyan

The nation-state has been the predominant model that underpins political thinking in the modern age, stresses Karthick Ram Manoharan, the author of Periyar: A Study in Political Atheism. “When this combines with religion, it can have disastrous consequences. Many anarchist thinkers, among whom I place Periyar, have challenged this. But both the nation-state and religion are powerful entities.”

Manoharan doubts if we can see a mass public atheist movement in India in the foreseeable future. “Defending the Nehruvian model of secularism itself is going to be a gargantuan task,” he adds.

When we are in politics, we cannot completely alienate ourselves from the aspirations, beliefs, fears and hopes of the society. Out of respect for the collective, an individual in politics does not and cannot impose his or her faith on the society – Pawan Khera, Congress

Pushback is increasingly difficult now, and questions arise in the absence of official data and a Census. This is despite laws prioritising Hindu majoritarianism and punitive actions against conversions.

Lawyer Gautam Bhatia points to a 2014 judgment by the Bombay High Court, which expanded the provision of Article 25 of the Constitution. Article 25 guarantees the freedom of conscience as well as the freedom to profess, practice and propagate any religion. The court in its judgment allowed persons to declare “No Religion” on governmental forms that require declarations of religion.

Bhatia reveals that the petitioners were, in fact, members of the “Full Gospel Church of God”, which believes in Jesus Christ but not in Christianity or any other organised religion. They had, therefore, made an application to issue a gazette notification stating that they were not Christians but, rather, belonged to “No Religion”, which was finally granted by the court.

In 2016, a two-judge Supreme Court bench in the case ‘G. Balakrishnan vs State of Tamil Nadu’ similarly decreed that the petitioner was under no obligation to state their children’s religion or caste to get them admitted to educational institutions.

These few legal wins keep some going. For Ahmedabad’s Rajveer, the Supreme Court’s observation that Hinduism is not a religion but a way of life actually pushed him to further his cause.

Rajveer’s individual beliefs haven’t translated into political reality, but he says he has grown more attached to his atheism. Others like Satnam Daun go a step further, insisting that their identity is a response to Hindutva.

Daun says he fought his son’s OBC certificate court battle because he felt this government was trying to classify Sikhs, Buddhists and even Jains as ‘Hindus’. “I could have filled in ‘Sikh’ for ease but it’s not who we are. They want to make it ‘us versus them’ (mainly Muslims, and Christians), so, if I chose to put myself in a religious category like Sikh or Hindu, I would have been playing to their agenda. Hence, I wanted ‘Others’.”

Meanwhile, for the rationalists, it’s business as usual as their meeting draws to a close. Ludhiana’s zonal head Surjeet Daudhar comes to Barnala with a large roll of plastic. Daudhar was booked by police in January 2024 after he made a Facebook post about 300 alternative Ramayanas, which he shared on the occasion of the Ram temple inauguration. Unfazed, he unfurls and holds up a flex banner that says: “Are jyotishis (astrologers) scientists? If they are scientists, please answer the questions listed below.”

Neither he nor Rajinder Bhadaur find themselves able to react to the sacrilege-accused’s lynching. But they’re off to engage with people using this banner. They will head to Moga later in the day.

“Someone is claiming to train children to read with a magical third eye. We will make him sign a bet for Rs 10,000 to prove this. Let’s see if he accepts,” Bhadaur says.

The video of the lynching has stopped playing; a ‘magic video’ appears on his phone screen now.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

I am curious to know why the ex muslim community has been specifically left out of this article. Only Hindu and Sikh atheists have been covered. Ex muslim movement is gaining a lot of ground in India. You should write article on that as well.

I have always noticed how “others” is missing from the dropdown menu, and I can remember “others” being included in drop down as early as 2018 but now it’s missing almost every where. I want “atheist” being listed as an option.

I am an atheist because my family is so pious. I just can’t believe how anyone believes in the obvious lie called religion. Annoying and frustrating. My disdain for religion originates mainly from the unholy and ugly site of bhakts following thug godmen, almost as if slaves would follow their masters.