Noida: Upendra Khari was at the wrong place at the right time. He heard the thrum of power saws as he approached the derelict Daewoo Motors factory in Greater Noida. It was a route he had taken for 30 years—first as an employee, and then later as a union leader demanding unpaid dues after the factory shut down. That day in June, he saw a scene of ecological plunder. A group of men were hacking away at the trees, others were loading trunks onto a waiting truck. When Khari and other protesters tried to stop them, muscled bouncers surrounded them.

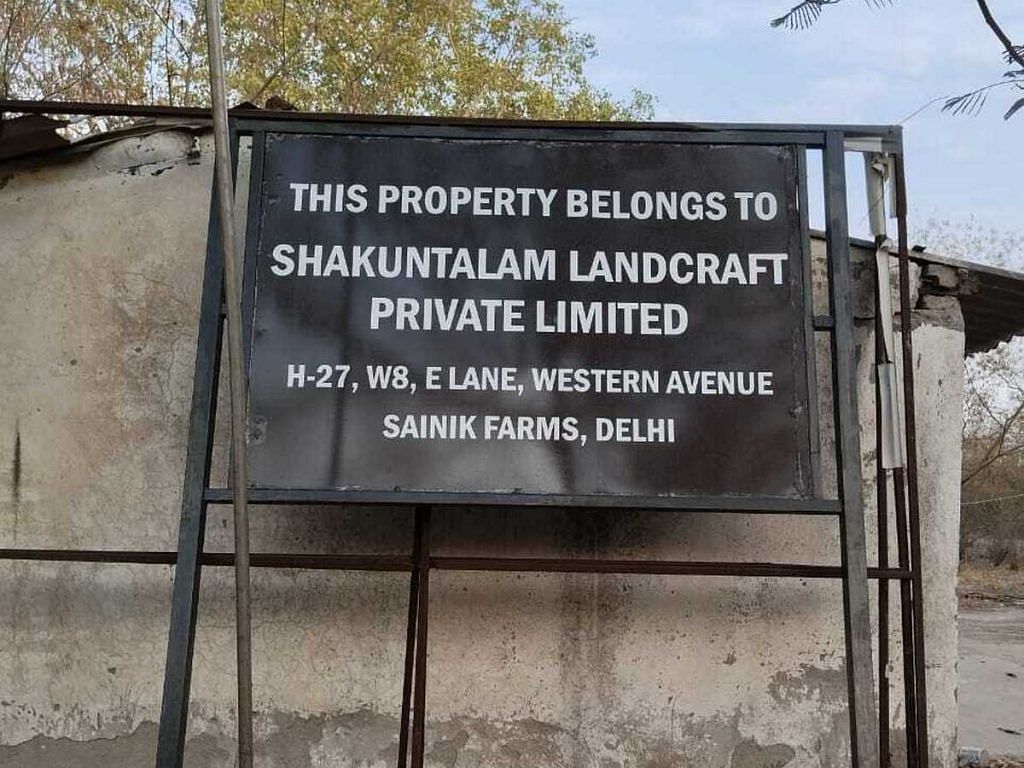

A month later, on 9 July, forest officials took the drastic step of sealing the factory grounds after another wave of destruction. At least 900 trees on the 204-acre expanse lay felled, victims allegedly of the new owners of the property, real estate company Shakuntalam Landcraft. It was the first time a private property in Noida had been sealed for the massacre of trees.

“This is the first time we have had to seal a [private] compound for violation of the Tree Protection Act,” said PK Srivastava, divisional forest officer, Gautam Budh Nagar. “It is not just because of the scale of tree felling. Despite a previous warning, the felling did not stop. We had to take action.”

But the battle is far from won. The Uttar Pradesh government plans to increase the state’s tree cover from 9 per cent to 15 per cent by 2030, a Rs 1,000-crore endeavour, but regulating felling on private property is a formidable challenge.

By law, the trees are protected. Uttar Pradesh’s Tree Protection Act, 1976, covers not just trees in public spaces that are vulnerable to development projects, but also those on private properties.

The perception is that you can do anything illegal just because it is UP. But that is not true – we have strong state forest laws, and stringent action is often taken against perpetrators

-Vikrant Tongad, advocate and environmentalist

But the Gautam Budh Nagar Forest Department, which oversees Noida, Greater Noida, and surrounding villages, is severely understaffed, with less than 50 employees. As one official admitted, it’s physically impossible for them to monitor what goes on behind garden walls.

“Whether it is private or public land, the law is the same for all trees. What we need is to develop the necessary surveillance mechanism to actually be able to implement our strong tree protection laws,” said Akash Vashishtha, a lawyer and environmentalist based in Uttar Pradesh. “Areas around Delhi-NCR are even more susceptible to tree felling for development purposes and they need to be policed better.”

For now, forest officials have registered a case against new owner Shakuntalam Landcraft, but let the supervisor and labourers go. Residents estimate that a total of 2,000 trees had been felled at the Daewoo Motors factory ground, far exceeding the official count of 980.

“We planted trees in this factory compound with our own hands every year as employees,” said Khari. “Now when these people were cutting them down, there was nothing we could do.”

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around, does it make a sound? This old adage applies equally to trees felled on private property.

Also Read: SC set to hear contempt case against DDA, here’s a look at curious cases of ‘missing trees’ in Delhi

A warning flouted

The felling of the trees might have gone unnoticed had it not been for Khari and the other workers, who had been protesting in front of the factory since 2012, having exhausted other measures to get pending compensation since they lost their jobs in 2003. With the musclemen standing guard, Khari realised he couldn’t stop the carnage himself, so he quickly contacted Vikrant Tongad, an advocate and founder of the NGO Social Action for Forest and Environment.

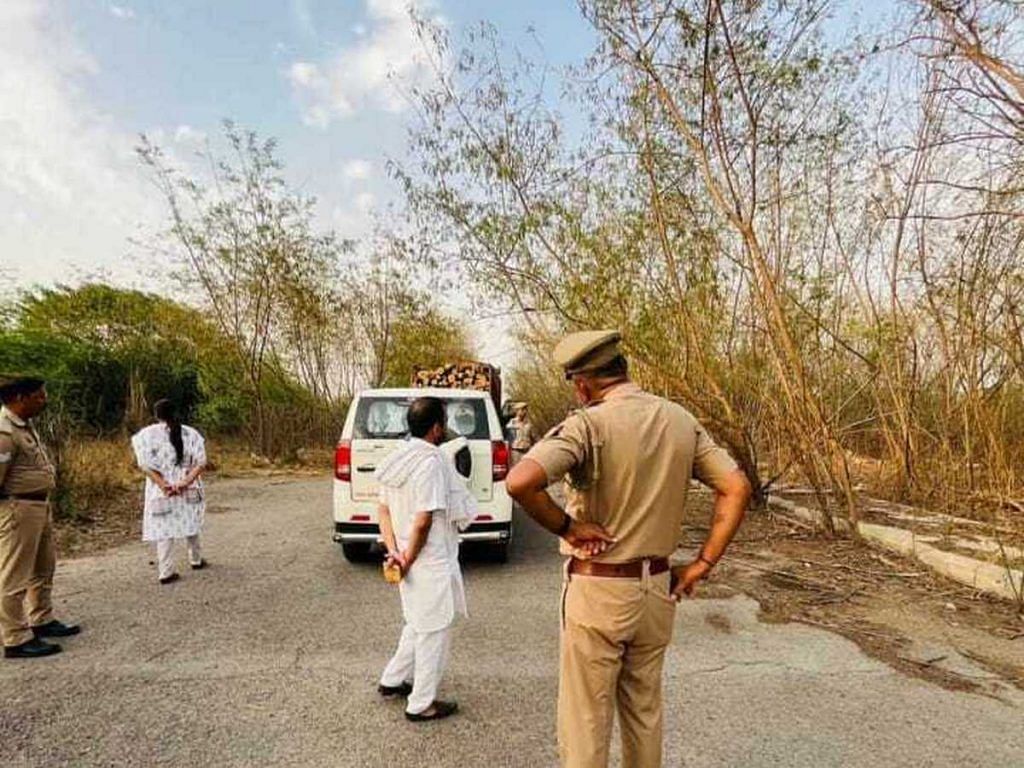

“We didn’t have the forest department’s number, but we knew Tongadji would immediately take action,” said Khari, recalling the events that unfolded on 9 June. But by the time the forest department officials arrived, two trucks laden with logs had already left the scene.

The one truck that officials managed to seize was filled with hacked jamun, neem, sheesham, eucalyptus, and peepal trees. They registered an H-2 case—the Forest Department’s equivalent of a first information report (FIR)—against Shakuntalam Landcraft for illegal felling and gave a strict warning to the supervisor present there.

This did not deter the perpetrators. Just days later, on 25 June, Khari and the others discovered a fresh pile of logs near a broken boundary wall in the factory premises, seemingly cut under the cover of night. They immediately alerted the forest officials.

“At first, the department told us that these were the older logs that Shakuntalam was clearing up,” said Khari. “But we know every corner of this compound and we could tell these logs were brand new. We insisted the department come down and do a proper inspection.”

Following a second inspection and another H-2 case against the company, the forest department sealed the factory on 9 July in the presence of the police, the district magistrate, and Shakuntalam’s representatives. But where there were once hundreds of tall trees, just stumps remain.

“The perception is that you can do anything illegal just because it is UP,” said Tongad, an advocate and environmentalist based in Noida. “But that is not true—we have strong state forest laws, and stringent action is often taken against perpetrators.”

The Print contacted Shakuntalam Landcraft via email for comment. This report will be updated if a response is received.

As is often the case, there’s a mismatch between the rigid requirements of the law and the existing capabilities of the Forest Department to enforce them, given limited resources and staff.

Forest to ‘industrial park’?

The 204-acre factory area, situated just a few metres from Surajpur Wetland, is one of the largest in the NCR. When it was under the South Korean car company Daewoo Motors, it was prime real estate in Greater Noida and boasted a vast green cover, according to Tongad.

However, Daewoo’s 2003 bankruptcy and withdrawal from India threw thousands like Khari out of work and left the compound in disrepair. Machinery and equipment were sold as scrap to recoup bank loans, while invasive species like Prosopis juliflora overran the neglected premises. Amid this, a legal battle over land ownership raged.

In August 2023, the Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) put the entire factory compound up for sale via an e-auction. This was done at the behest of Asset Reconstruction Company India Limited (ARCIL), which was managing Daewoo Motors’ stranded assets to recover remaining dues for companies including ICICI and the Uttar Pradesh State Industrial Development Authority (UPSIDA).

In last year’s auction, Shakuntalam Landcraft won with a bid of Rs 359 crore, but UPSIDA contested the result.

Anil Sharma, Surajpur division head of UPSIDA, claimed that despite offering a 10 percent premium over the winning bid, it was barred from participating in the auction.

“There’s dues worth over Rs 400 crore that the Daewoo Motors factory owes us in arrears and such,” he said. “But since we were the original owners of the land we were willing to buy it back and forgive the dues. The property itself is worth more than Rs 1,000 crores today, so why would ARCIL settle for selling it for less?”

UPSIDA approached the DRT to complain about the “unfair” auction process, demanding their Rs 400 crore dues be paid first and the auction be held again. The DRT initally set aside the auction on “cartelisation grounds”—indicating tampering with the process by the winner— but Shakuntalam appealed against the order and won.

While the tribunal deliberates the case by UPSIDA, Shakuntalam was been granted ‘possession’ in May under the condition that they do not sell, mortgage, or create any ‘third-party interest’ until the dispute is settled.

However, Shakuntalam’s ambitions for the site are no secret. In September 2023, Shakuntalam Landcraft director Pallavi Gupta spoke to mediapersons about plans for a “gold-rated industrial park” housing 600 MSMEs, with a projected investment of Rs 1,500 crore.

An old attachment

It is not just UPSIDA and Shakuntalam with stakes in the Daewoo Motors property. Even former Daewoo employees, who have been picketing the gates in an indefinite strike, are invested in the land and its trees.

Khari, a factory operator from 1997 to 2003 and his fellow Daewoo-DCM Workers Union members Amarjit Singh, Anup Singh, and Satendra Bhati have been showing up here for over a decade, demanding the salaries, pensions, and benefits promised to all former workers by the company. At its peak, the workers say, the Noida factory employed some 2,000 people.

The protesters are embittered by the experience yet nostalgic about the property.

“Buildings only made up 30 per cent of the total compound. The rest was all open green spaces,” recalled Anup Singh, who joined the company in 1987. “We even had an entire gardening department that looked after the trees, plants, and greenery.”

The workers speak fondly of the company’s egalitarian management and the prestige associated with working for a once-leading global automaker. Since Daewoo’s departure, the workers’ union has been battling the Debt Recovery Tribunal, demanding that their dues—which they claim to be worth Rs 360 crore—be included in the total recovery from the sale of the compound.

“Along with fighting the case in the DRT, we have been sitting in protest here every day since 2012,” said Khari, sitting under a tarpaulin shed the union has set up right outside the factory. “But before Shakuntalam took over the premises sometime in May, we have never seen anyone tampering with the trees or anything else inside the factory.”

Also Read: 5 mn large trees felled in India in 2018-22 — Danish study’s ‘unexpected, unsettling’ findings

Breaking the silence

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around, does it make a sound? This old adage applies equally to trees felled on private property. Only on rare occasions are these actions noticed or any noise made about them.

In the Daewoo factory case, the Forest Department registered the case against Shakuntalam under the Tree Protection Act 1976, which is unique to Uttar Pradesh. The management of trees is regulated by state governments, according to the Indian Forest Act of 1927, which means they can make their own rules regarding the felling, pruning or removal of trees in their territory.

UP is particularly strict about it.

“In this state, even if there is a tree on your property that you have grown, you would need the forest department’s permission to cut it,” said Tongad.

However, enforcement, particularly on private land, often falters. And activists and concerned citizens are often the first line of defence.

In October 2021, for example, the forest department in Ghaziabad registered a case against former Mayor Ashu Verma for illegally felling four fully-grown trees in a private space near his house. The matter was brought to their notice by local activists, including environmentalist Akash Vashishtha.

Similarly, Tongad and other residents exposed the illegal clearing of nearly 300 trees for a petrol pump in Greater Noida West in 2019, after which the forest department imposed a penalty on the company.

As is often the case, there’s a mismatch between the rigid requirements of the law and the existing capabilities to enforce them, given limited resources and staff.

Local awareness of tree protection laws and how complaints can be registered with the department would go a long way in ensuring tree protection in urban areas

-Akash Vashishtha, environmental activist

“Much like the police, the forest department too has informants and a surveillance mechanism that informs them about illegal activity,” said Vasishtha.

“But when these mechanisms fail, it has to be up to us to inform the department and ensure strict action is taken.”

Further, DFO PK Srivastava pointed out that not all tree felling warrants a case being registered.

“Sometimes people think invasive species aren’t important and cut them without the required permissions,” he says. “Other times, they don’t even know they need permission.”

In such cases, the punishment involves fines and planting two additional trees for each one cut.

For Vashishtha, the most practical solution to an overwhelmed forest department is building public awareness.

“Local awareness of tree protection laws and how complaints can be registered with the department would go a long way in ensuring tree protection in urban areas,” he said.

Vashishtha praised the forest department’s response in the Daewoo Motors incident, calling it a “rare case, laying a strong precedent in tree law jurisprudence in Uttar Pradesh”. But Tongad gives much of the credit to the protesting workers who brought the incident to light and compelled the forest department to act.

The employees, meanwhile, are continuing their vigil outside the compound’s gates. They are hoping to be heard but are also keeping their own eyes and ears open.

Upendra Khari recounted how he and five others chased down the last truckload of felled trees on 9 June, stopping its departure and handing it over to the forest department.

“If there is any other such incident here again, we are prepared to stop that too,” Khari said. “Even if we don’t work here anymore, it is still our responsibility.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)