Ajmer: In the early ’90s, when Santosh Gupta entered the Dainik Navajyoti office—one of the few Ajmer-centric newspapers in circulation at the time—he would leave a trail behind him: a line of reporters, camerapersons, and curious citizens. The gritty, scrappy reporter had become a local celebrity after breaking what is now referred to as the ‘1992 Ajmer Gangrape and Blackmail Kaand (scandal)’.

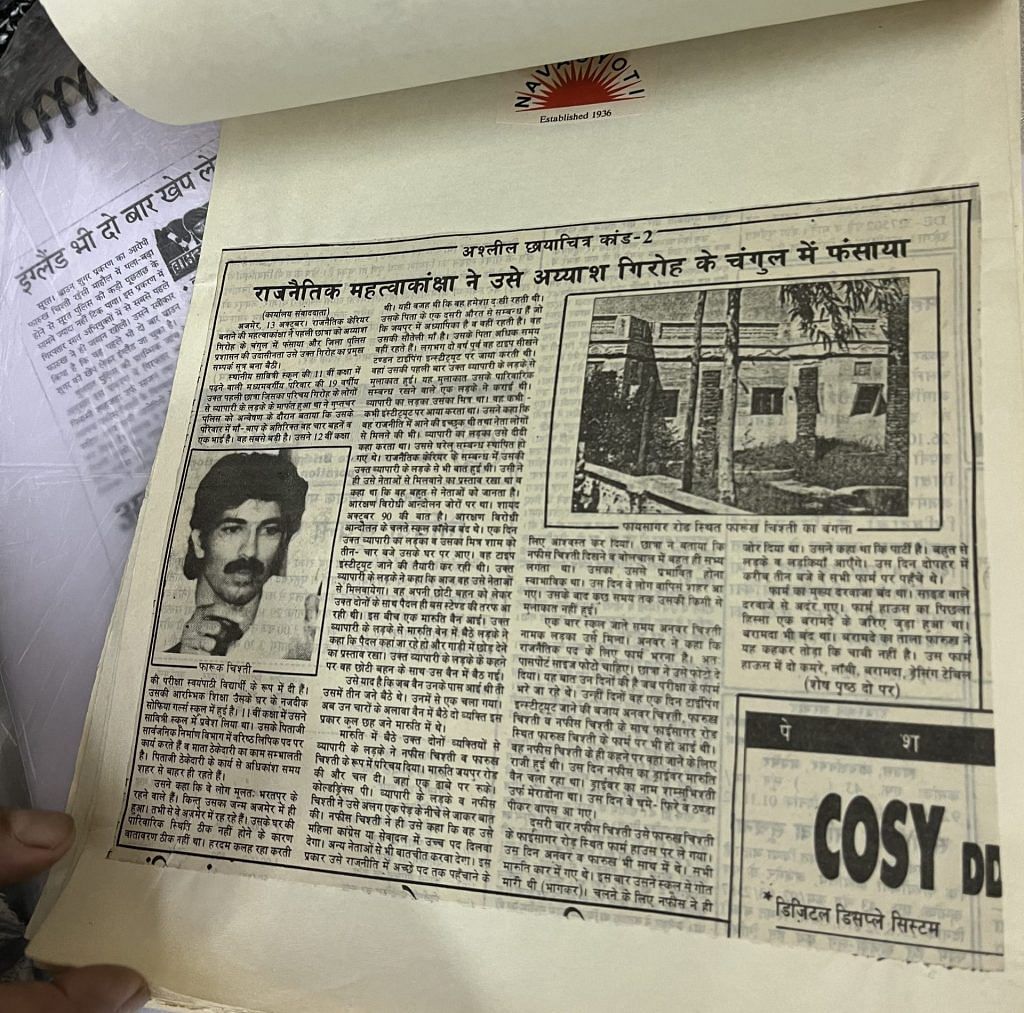

It was Gupta, not the police, who opened a Pandora’s box, unveiling a sordid tale of sexual violence that was later made into a Bollywood film released last year. The powerful Chishty duo, Farooq and Nafis, who belonged to the extended family associated with the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, along with their friends, gangraped and blackmailed scores of school-going girls for months on end.

Even before the FIR was registered, Gupta’s story had made it to the paper.

“This case has survived and stood the test of time only because of the media,” he said. “Otherwise it would be long dead.”

A handful of relentless journalists kept the story alive, doggedly pursuing every glacial development and maintaining public interest. It was a time before the phrase ‘media trial’ became a handy stick to beat journalists with. It was before 24×7 TV channels and cell phones—when telex and fax machines were the norm in newsrooms. Journalists weren’t brand names back then.

This case has survived and stood the test of time only because of the media. Otherwise it would be long dead

— Santosh Gupta, Dainik Navajyoti reporter who broke the story

The case’s enduring impact partly lies in its many layers—a complex web of crime, victims who became hostile survivors, and the unfulfilled promise of comeuppance. But it is also due to the unlikely arbiters of justice. Years before a court reached a decision, victims and villains were subject to an unforgiving media trial. It was a dubious time for media ethics—and journalists, much like bees, were swarming.

“The media was watching us 24 hours a day. It was almost impossible to record victim statements because they would be following us,” said Dharamvir Yadav, a police officer who was part of the CID crime branch team. He said ThePrint’s Jyoti Yadav was the first to contact him. They were forced to record statements in odd locations, including the backseat of a car and a poultry farm. Some were even taken to Jaipur. “They were everywhere.” Investigation times were often changed simply to avoid the media.

Journalists would set up outside a local circuit house where the investigation was being conducted, practically frothing at the mouth for even the smallest scrap of information. Most of what they reported made it to the next day’s papers. But in several cases, they were simply witnesses or bystanders called in for questioning. The media’s manic, feverish coverage also meant misinformation.

Several women who were simply students of Sophia’s or Savitri—the two schools from which most victims came—were incorrectly identified as targets of the crime.

The city was on edge. Then, newspaperman and ‘history-sheeter’ Madan Singh’s Lehron Ki Barkha, a small newspaper of 2.5 pages, began publishing names. A gang leader’s sisters were incorrectly identified as victims, which led to Singh’s murder by members of the ‘gang’.

It was Yadav’s first crime-branch posting, and no subsequent stint has matched it. The entire year was spent trying to unravel these two intertwined cases.

Policemen like Yadav and a handful of journalists were pushed straight into the deep end. They were in their mid-20s and early 30s, and Ajmer had never seen a case like this before. There were no precedents to follow, no templates to use. They were forced to forge their own bumpy paths, which they continue to traverse.

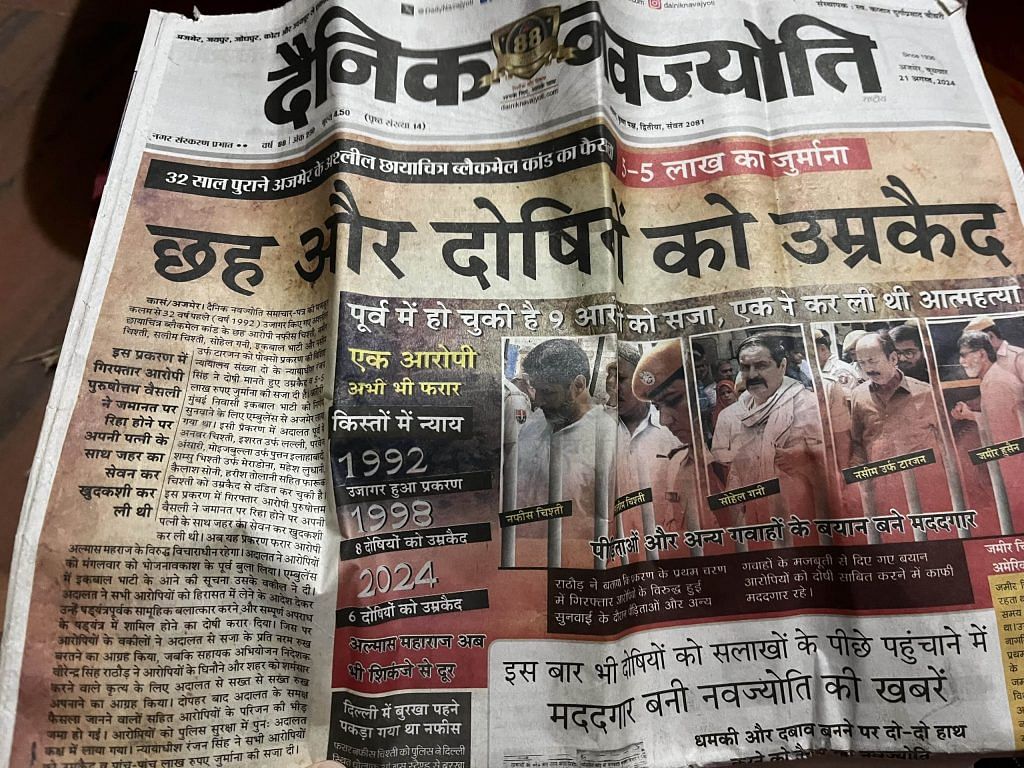

Last week, after 32 years, a POCSO court in Ajmer sentenced six accused to life imprisonment and fined them Rs 5 lakh—marking a passive, lukewarm end to a case that had shaken the city to its core. On the surface, it seems Ajmer has moved on. At night, single women stroll around malls. After a day’s work, they get into shared cabs, leaving their conversations unfinished.

But PK Srivastava hasn’t moved on. Thirty-two years later, he paces the Ajmer District and Sessions Court complex, sipping tea and chatting with lawyers—he’s still on the hunt. Once a reporter with Madan Singh’s paper, this has become an unyielding assignment that is now an indelible part of his identity.

And there’s one incident that has cemented it.

“When Ashok Gehlot was chief minister, he visited Ajmer and met with policemen and lawyers,” Srivastava recalled. “He rested his arm on my shoulder and said, ‘This is a case in which journalists know more than the police’.”

It was the proudest moment of the 65-year-old’s life.

Also read: Gangraped in teens, visiting courts as grandmothers: 1992 Ajmer horror is an open wound

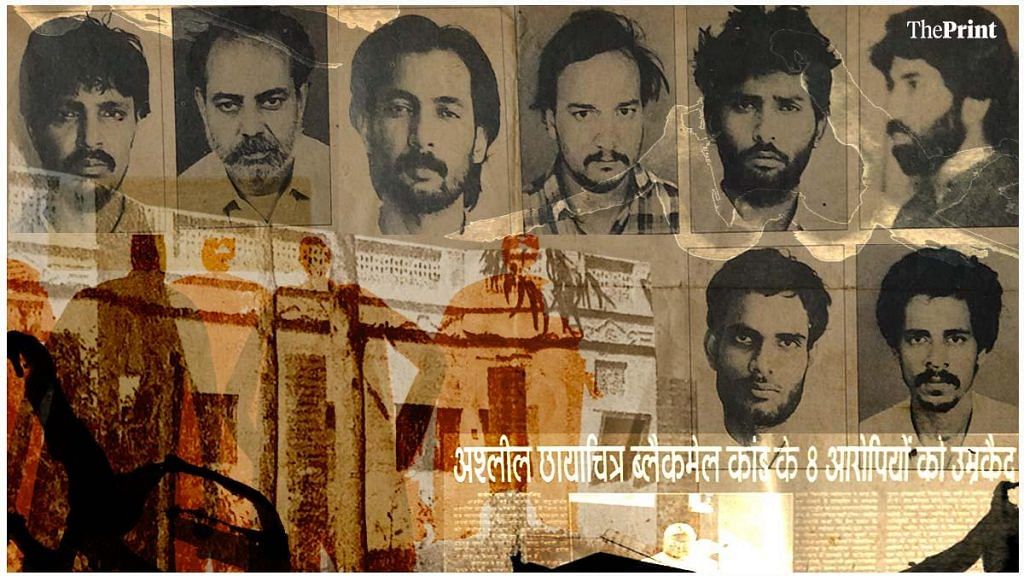

The infamous photograph

On 16 May 1992, a grainy photograph was published in Dainik Navajyoti. A young woman, her face obscured, was positioned between two men—one kissing her cheek while the other beamed into the camera, both grabbing her breasts.

This picture became a totem for the investigating officers.

“We had nothing except an FIR. And then the photo was published,” said Yadav. “Her whereabouts were unknown, but we started scouring the lanes around the dargah. Finally, we found her.”

The photograph set the entire investigation in motion. The survivor in the photograph told ThePrint that she never knew it had been in the papers back then.

“All my photos have been shown in court. I’ve identified myself when journalists have asked if it’s me,” she said. “The truth is the truth.”

In a thin notebook, she maintains a meticulous record of the journalists who have called her over the years. Their names and numbers are written down. The first on her list is ThePrint’s Jyoti Yadav.

“It’s good practice. I might need them someday,” she said.

For years, no journalist approached her—she was never asked to share her side of the story. But now, following the verdict about 10 days ago, the floodgates have opened. She fields phone calls daily, inviting journalists into her home and recounting the 32-year-old ordeal that continues to shape her life.

“But I have to be careful. It’s also a question of respect and my standing in the neighbourhood,” she said. “I tell them all to meet me at the corner store first, and then I lead them in.”

She doesn’t want her neighbours to see her with journalists or anyone who might arouse suspicion. One of her nieces recently got married, and another needs to. Her past cannot sully their futures. Her first husband left her as soon as he found out—“the mehendi from my hands hadn’t even dried.”

“All of them talk to me with love and affection and tell me how sorry they are about what happened to me,” she said.

She narrates her rape with the pragmatism of a woman who has been asked to recall it time and time again, pausing and inflecting at all the right points. She was 18 at the time, one of her perpetrators was an acquaintance, and she didn’t understand what sex was. She had no idea what the men were doing to her.

“I am an innocent, simple person. People often take advantage of my weakness,” she said. She doesn’t necessarily mind the stream of journalists, but she is aware—“there’s only one story they want to know.”

Among her few cherished possessions, which she guards zealously and takes out from their plastic bags when journalists visit, is a copy of Dainik Navajyoti. On its front page, the accused who have finally been sentenced are visible, in all their lost glory.

Also read: ‘Shows evil meets a bad end’: Ajmer gangrape survivor finds closure 32 yrs on as 6 accused sentenced

One reporter, many followers

Gupta is an adept storyteller, perfectly dramatic and now accustomed to being on the other side of the story. He leans against a black and beige leather sofa in his home, with one of his many awards, adorned with decorative pink flowers, behind him.

“The year was 1992. The rapes created a different kind of atmosphere, and in the process, our social harmony was lost,” he declared. “Ajmer is a small town that used to have a certain innocence. Boys and girls seldom interacted. Each day was structured and predictable.”

Once he exposed the rapes, following a tip-off from a photo-reel developer who received images of the sexual assault, the city’s restive small-town charm was wrenched away—and in the process, Gupta became a mini-celebrity.

“There’s not a single TV channel with which I haven’t done a live [interview],” he said, with only feigned modesty. India Today published an entire article dedicated to him, featuring a photograph of him in his younger years. Beneath it, the captions reads: “Sensational Scoop.”

Gupta’s reports became essential. “I used to keep all of Santosh Gupta’s reports. They had practically formed a book,” said Charanjeet Singh Oberoi, a defence lawyer for one of the accused who was acquitted.

As the story began to spiral out of control, with public pressure reaching its boiling point, there was a fevered demand for copies of Dainik Navajyoti. At the time, there was only one other paper, Dainik Nyay, that rivalled it. Dainik Bhaskar entered the scene in 1997.

“We used to have cylinder machines then. We could only print between 2,000 and 5,000 every hour,” said Gupta. “But the demand rose, and we needed 60,000 copies. Everyone wanted to read Navajyoti.”

Reporters who covered the story spoke of their dogged commitment to journalism and the care with which they verified information. But according to Gupta, they were merely taking advantage of the limelight.

“Reporters were staking out the girls’ homes, promising them justice and pocketing money from their families. They had very poor ethics,” he said. Srivastava also admitted to tracking the students down at their homes and interviewing their families. Gupta, on the other hand, claims to have abided by his “religion” of journalism.

Such was their hold over society that families across Ajmer would approach them at their offices to enquire whether certain girls were victims.

“No one wanted to marry girls who were victims or came from victim families. So they would ask us to tell them,” said Srivastava. According to Gupta, this was a regular occurrence. People believed in the media more than they did the police.

Dilip Kumar, deputy news editor at Rajasthan Patrika, was earlier a legal reporter. He joined Patrika in 2002 and is a year away from retirement. But this is a story he can’t stop covering.

“It’s a moral offence, and the media supported the victims fully. The public was on our side,” he said. According to him, there aren’t any upcoming reporters who can replace the old guard. “They don’t have that passion for the story. How can they? They weren’t even born. There’s no legal reporter who’ll take this story now.”

Also read: Bollywood, Netflix smell story in 1992 Ajmer gangrapes. After court, now privacy battle begin

Obsession for a new generation

The first FIR was registered at Ganj Police Station, now manned by a completely different generation of policemen. The station’s head constable, Prabhat Kumar, was still studying in 1992. Ajmer, according to him, has changed completely since. Normalcy has been restored. “It’s the difference between night and day,” he said.

For the police officers of his generation, the investigation conducted by their predecessors is something to take inspiration from.

“They did an excellent job, and we have a lot to learn from them. Thanks to them, the public started believing in the police,” he said.

But for Yadav, who retired from service in 2011, it’s like it’s never going to end. “This case has been a part of my entire life,” he said. Almas Maharaj, one of the accused, is still absconding. If he is found, the saga in court will start once again.

However, in many ways, it also has ended. Sushil Paul, a local journalist who runs an Ajmer and Jaipur-based online platform called MTTV India, finds that many of his audience members aren’t aware of the intricacies of the case. It’s been expunged from their lives. Now, it’s more of a morbid fascination, the kind that drives true-crime enthusiasts.

“Ajmer is a small town, so this case will always have a lot of publicity,” he said. “But now, there’s a new generation. It’s been over 30 years. They want to know about the case that ruined their city’s reputation,” he said.

His platform is visual-only, and to create content, he relied heavily on newspaper archives. “The visuals are most important. When the accused was being brought to court, we had to use their photographs,” he said. His audience wants to know the nitty-gritty details—where was the farmhouse to which the girls were lured, and how did the photographs make it into the public domain.

Gupta has cupboards filled with old photographs, copies of newspapers, and the articles he has written over the years. He knows they will come in handy at some point.

“But they’re getting ruined now, and there’s no space to keep them,” he said, referring to one photograph of sexual assault that has grown yellow with age. His house is under renovation, and he no longer has room for his prized papers. Srivastava’s articles were attacked by an onslaught of termites. “What’s the point of keeping them anyway?” he said.

Gupta is no longer a journalist and now works in the public relations department of Mittal Hospitals. His family doesn’t always understand his journalism and has been “troubled” by it in the past. “I made some sacrifices. There were nights I would be at work until 3 am,” he said. He remembers it all—his yellow bag with his tape recorder, camera, notebook, and a knife for good measure—and his moped bike.

There’s another enduring memory. When the story was at its peak, he was invited for tea at the home of a politician. The politician didn’t mince words. “This is a story of a home. And it needs to be buried within its premises,” he said. Gupta didn’t respond.

(Edited by Prashant)

Ms. Anatara Baruah, just like Ms. Jyoti Yadav, has been under the tutelage of Mr. Shekhar Gupta and has turned out to be a perfectly “secular” journalist.

Just like Ms. Yadav, she too has very carefully crafted the article so as to brush under the carpet the brazenly communal nature of the heinous crimes committed. The story has been “secularised” and presented as if it’s just another grooming gang story – an approach taken by Mr. Shekhar Gupta too on his CTC episode.

No mention of the religious angle of the crime has been made. Facts of the case, most certainly known to both Ms. Yadav and Ms. Baruah, were deliberately suppressed which would make it appear like a “secular” crime.

Kudos to Mr. Shekhar Gupta for mentoring such “secular” journalists.