Rohtak: Sapna’s body lay on a stretcher at a Rohtak mortuary – thin frame, bullet wounds on her back, and no one from her family waiting outside. Her brother Sanju, allegedly shot her dead on Wednesday night – while she was asleep – to “restore” family honour. Three years earlier, Sapna had married a man from her own Chamar caste and Kahni village – a union the community considered a deep insult. On Wednesday night, Sanju decided to settle it.

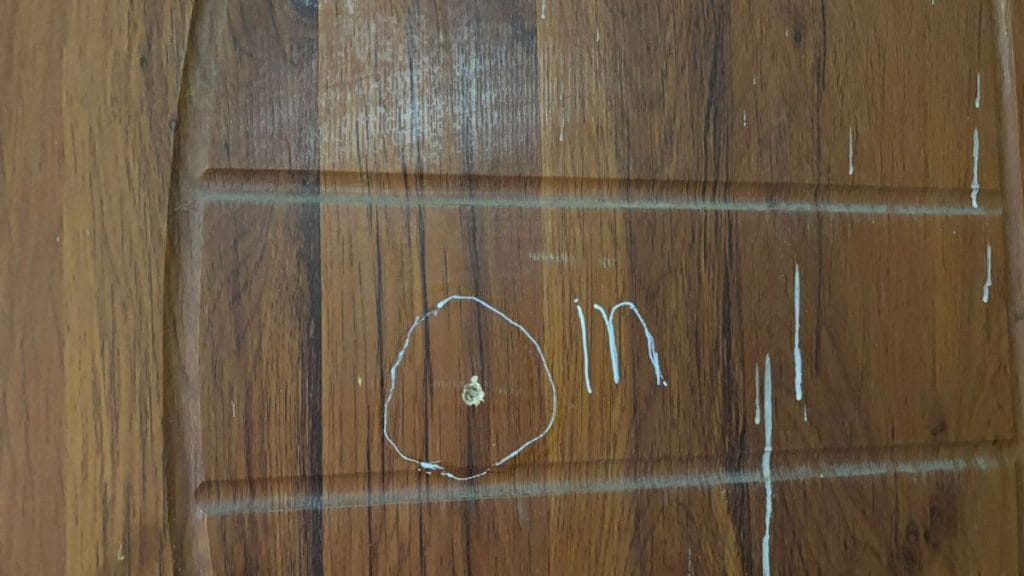

Sapna, 23, was sleeping in her house when Sanju and three of his accomplices allegedly climbed the courtyard wall of her in-laws’ house and entered her room at around 9:30 pm. Their stated motive, according to police, was to kill both Sapna and her husband, Suraj. First, Sanju shot Sapna dead with a single bullet. When Suraj’s younger brother, Sahil, tried to intervene, they shot him as well. Only pockmarks from bullets remain on the door and floor where Sapna slept.

Suraj, 23, an auto-rickshaw driver was out on duty, and narrowly escaped the attack. Police say Sanju planned to track him down later that night but they arrested all four accused in time. Sanju was shot in the leg by the police while he was trying to flee.

Across several Haryana districts, a case like Sapna’s was once a familiar headline. In the 2000s, so-called “honour killings” dominated debates around the state’s khaps, sparking outrage and a rare conversation on caste, clan and marriage. Despite Sapna’s earlier warnings to the police and sarpanch, her killing is neither sudden nor unusual in this belt of Haryana.

Marriages within the same village or gotra, though legal, are still treated as violations of community order, often punished through boycott, eviction, forced separation, or, at their extreme, murder. In many districts, khap norms continue to overshadow the law, pushing couples into hiding or displacement. Haryana today remains among the top states for “honour killing” cases, second only to Jharkhand.

Families continue to enforce old rules through new violence, and the remorse is none. In Sapna’s case, her mother did not grieve her daughter’s death because she had brought “shame” to the family.

“Why did Sapna marry within our village? We will not take the blame,” Sapna’s mother Anita said, expressionless.

A village that knows, but won’t say

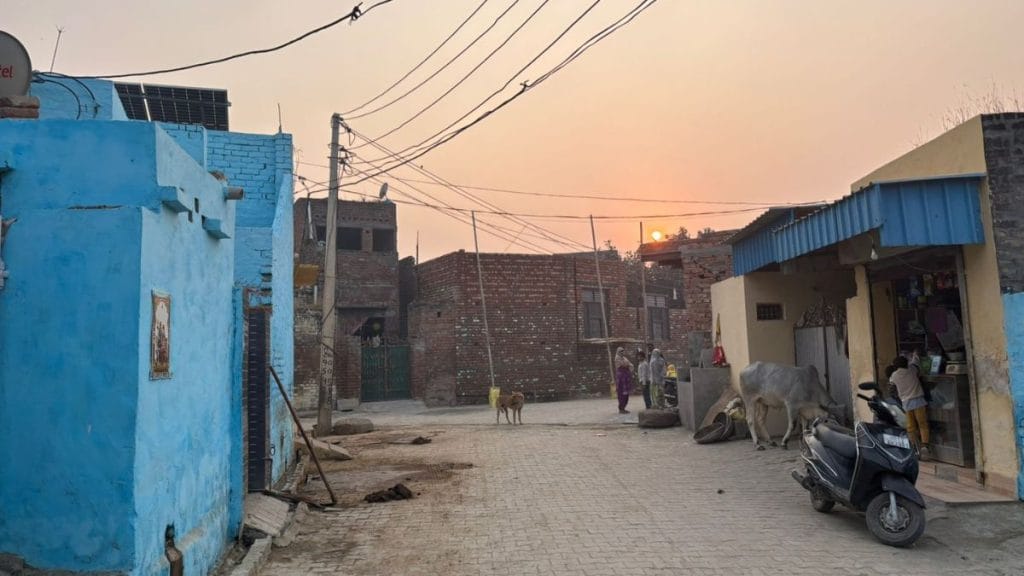

Kahni village, around 20km from Rohtak, sits in an uneasy quiet a day after the murder. Not mournful silence, but a rehearsed one. Conversations skid around Sapna’s name. Words like sharm (shame) and apman (insult) appear often, but grief does not. Some villagers claim they “heard nothing.” If anyone talks about Sapna’s murder, they defend it by saying, “the rule was broken.”

What prevails is denial – an insistence that the problem was not the murder, but the marriage.

For decades, Haryana’s khaps enforced rigid boundaries around marriage: same-gotra, same-clan, and same-village unions were forbidden and treated like a crime. Acting as informal courts, they decided the fate of couples who violated social codes. But in a recent, rare shift, khaps in parts of Haryana broke a century-old taboo by allowing marriage between certain linked villages, ThePrint reported earlier this year. Things are beginning to change but in Kahni, the norms remain intact.

“Same caste and village marriages don’t happen here,” Sarpanch Pradeep Khatri said calmly.

When Sapna and Suraj got married, the panchayat set the rule: they must leave the village.

“We didn’t have a problem with ‘such’ marriages, but with the rehen-sehen (how people live together),” the sarpanch said, adding that leaving their home is a must if couples marry in the village.

DSP (City) Gulab Singh is more blunt about these customs.

“These marriages are not allowed socially. Caste is not always the issue. The couple were given protection when they applied. Once they returned, tension started again,” Singh said.

Experts call village exogamy — the idea that you can’t marry from your gotra or village — a “deep-rooted problem”.

“Classical patriarchy has left women’s sexuality to be controlled by men. Be it a brother or a father,” JNU professor and sociologist Surinder Jodhka said.

Also Read: Haryana khap breaks 100-yr-old marriage taboo between villages. Now waits for 1st wedding

A love story the village refused

Suraj and Sapna grew up a few lanes apart. They met in Class VIII at the local government school. By Class X, the relationship angered both families so much that the school struck their names off its rolls. Neither ever studied again.

What began as teenage friendship turned into a long, steady partnership. In their early twenties, they married in court. There were no celebrations, only fear.

The village responded with a boycott.

“They broke our khap maryada (honour), this is not what our Hindu culture says,” sarpanch Pradeep Khatri said.

“Kaand (scandal)” is how many described the marriage. But Sapna’s murder does not make the cut.

Three years ago, Sapna approached the Sadar police station with a handwritten complaint. She said her family had threatened to kill her for marrying within the village. The complaint was taken and stamped. Police asked both sides to sign an “agreement” – essentially a promise to maintain peace. The threat remained. She was told to leave the village.

Within days, the couple left the village and rented a room in Rohtak. But the warnings continued through neighbours, relatives, and often from Sapna’s brother, the accused Sanju. The rent was high; Suraj’s earnings were limited. After two years, they returned to Kahni, not to reconcile, but because they could no longer afford to live outside. They avoided her family’s street.

Sapna’s in-laws say the questions started pouring in the moment they returned to the village.

“We kept quiet,” Nirmala, Suraj’s mother and Sapna’s mother-in-law, said as she waited anxiously outside the PGIMS operation theatre where Sahil, 20, her son, was being operated on.

The night it was over

On Wednesday night, Sapna felt nauseous and went to sleep early. It was a busy week; her son Dev’s second birthday was upcoming, as well as her brother-in-law Sahil’s. Clothes were washed, the house was cleaned, chairs were kept outside for guests. She spent Rs 250 on make-up earlier that day for the celebration.

Sapna’s mother-in-law and Sahil were chatting in the next room when they heard gunshots.

“We saw the CCTV footage and saw four men. Sapna couldn’t even scream, we used a bamboo stick to shut the door, but Sahil left the room to fight the boys who entered the house, and that is when they shot him in the stomach,” Nirmala murmured in a thick Haryanvi accent.

A daughter lost

At Sapna’s maternal home, no one speaks her name. No photographs remain, no belongings.

Her mother, Anita, sits on a charpai, showing no grief over her daughter’s death.

“Uske kapde, chappal, jo tha, sab phek diya (We got rid of her clothes and shoes),” Anita said.

She is worried about her son, who is in police custody.

“Kya police ne kuch bola (Did police say anything)? Has Sanju returned?” Her husband, father-in-law and younger son have also been detained for questioning.

Anita last met her daughter four years ago at a police station.

“She told me she won’t come back. I cut ties with her. She brought shame to our family. Whatever happened was bound to happen,” she said, insisting she knew nothing of her son’s plan. She also claims Sanju was home that night, and the police informed her over a call about the incident.

Anita says she did not want anyone to know Sapna was “their daughter” and the main problem was her return to the village.

“Why did she return? Look what problem it caused us. No daughter is accepted once she marries,” she said.

She cries only when asking the police to release the men of her family.

Sapna’s aunts and sisters refuse to talk about her death.

In Suraj’s home – where Sapna lived – the grief is open, raw. Nirmala, her mother-in-law, breaks down repeatedly outside the hospital’s operation theatre, wearing a suit stitched by Sapna.

Sapna loved sewing. Nirmala spoke fondly of her daughter-in-law who would dress everyone up during a festival.

The last words Sapna said to her were: “Mummy, I’m not feeling well. Can I sleep?”

Nirmala broke down.

“She wasn’t just my bahu. When my husband died, she told me she’ll be with me always,” Nirmala said.

An unsaid rule

In the lanes where Sapna and Suraj grew up, same-village marriage remains taboo, a rule older than the families who enforce it. Khap leaders defend it with conviction.

“I am not saying violence should happen,” Surender Dahiya, president of the Dahiya Khap, said. “But children must know what they can and cannot do. They should not hurt family pride.”

In the next breath, he calls Sapna and Suraj’s marriage unacceptable. He cites “scientific” and “Vedic” logic, and even “health concerns,” to justify the ban.

Sociologists caution against labels such as “honour killings”.

“This term gives us an easy route,” JNU professor Surinder Jodhka said. “Initially, these cases started with upper caste women marrying lower caste men, and it was a challenge in caste hierarchy. But Suraj and Sapna’s case sits on a different map of violence, as both belong to the Chamar community.”

For Jodhka, this has less to do with the rules broken, and more about bruised egos, threatened masculinity, and authority that collapses in front of a village.

“This is a family that is unable to accept the autonomy of a daughter they raised. When we call it honour killing, we avoid the complexity,” he added.

Khap councils from Rohtak, Jhajjar and Sonipat now meet annually to demand formal prohibitions: a ban on same-village and same-gotra marriages, a ban on live-in relationships, lowering legal marriage age from 18 to 16, and mandatory parental consent for love marriages. They warn of statewide protests if demands are not met.

Even as Haryana is infamous for honour killings, as per the latest NCRB data, in 2023, the state found itself on the second spot, after Jharkhand. The state reported six cases.

Haryana continues to record some of the highest numbers of honour-killing cases: six in 2023, the second-highest after Jharkhand.

Sapna’s marriage violated Kahni’s unwritten code. Her death reinforced it.

When police informed Sapna’s family that her last rites would be performed after the post-mortem, the family refused to claim her body.

“Why will we go for the cremation?” her mother said. “We had no association with Sapna. I will wait for my son and my husband.”

(Edited by Stela Dey)

About time we called a spade a spade and confronted the gheerah obsessed culture that we’ve imbibed with great devotion. This mindset has claimed far too many lives.