Somnath, Junagadh: There is an up-and-coming coconut capital in India. It is not Kerala or Tamil Nadu or West Bengal. It is Gujarat, where tender green coconuts are filling tempo after tempo heading to Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, and UP.

The stretch of NH-51 passing through Somnath, Junagadh, Valsad and Bhavnagar is now a coconut highway, from the swaying palms in the fields to the loaded trucks. In the past five years, more and more hectares have been taken over by coconut, and farmers say the fruit has paid them back in full. Green, tender, mildly sweet coconut is now the top cash crop of this coastal belt.

“Coconut for us is kalpavriksha [the divine tree]. It has become our lifeline”, said Naranbhai Solanki, a farmer from Somnath, and one of the early adopters and promoters of the crop in the area.

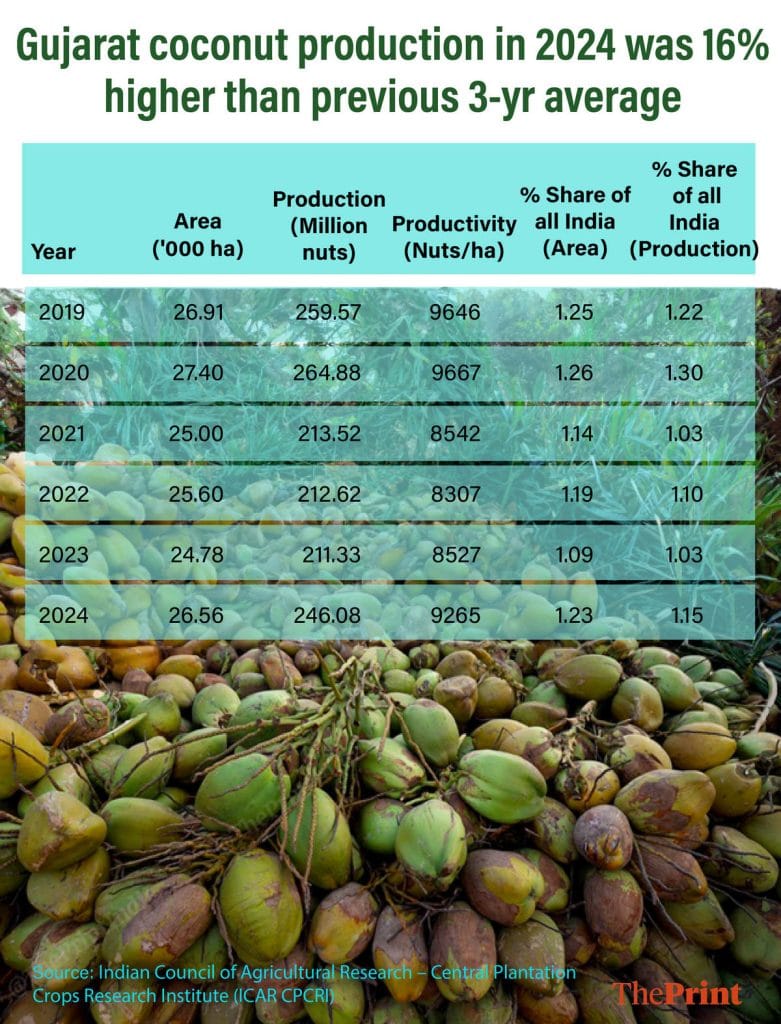

Of late, World Coconut Day on 2 September has become a celebratory occasion in Gujarat. This year, state agriculture minister Raghavji Patel announced that the area under coconut cultivation in the state increased by nearly 26 per cent from 22,451 hectares in 2014-15 to 28,197 hectares in 2024-25. As of now, Gujarat produces 260.9 million coconuts every year, with around 20 per cent reportedly harvested when tender, ranking seventh among all Indian states. But in North India, it reigns supreme, supplying about 40 per cent of the coconut sold in the region.

“In the coming years, Gujarat can emerge as a competitor to the southern states,” said S Jayakumar, who retired this year as the market development officer of the Coconut Development Board. “There is a scarcity of tender coconut in the country, and Gujarat just grabbed the opportunity.”

A major turning point seems to have come last year, according to K Balachandra Hebbar, director of ICAR-Central Plantation Crops Research Institute in Kasargod, Kerala. He said data over the past decade showed “no remarkable increase in area and production” until 2024, when there was around a 16 per cent rise in output compared with the previous three-year average.

Growers and horticulture officials say coconut production in coastal Gujarat has been growing for over a decade, but Covid boosted the market for the green variety. Doctors across the country were advising patients to drink tender coconut water instead of Pepsi and Coke, and the habit stuck. With nariyal pani becoming a go-to health drink, prices stayed stable, and farmers along the coast began adding more trees. Groundnut, the old mainstay, lost ground. Profits on coconut are as tall as the trees. Farmers say bigha revenue from coconut stands at around Rs 50,000-70,000, while groundnut rarely crossed Rs 30,000.

Unlike the South, where most coconuts go into oil and processing, Gujarat’s coconuts are grown for their refreshing water and creamy pulp, said Dr DK Varu, principal and dean of the College of Horticulture at Junagadh Agricultural University, who works closely with farmers. He added that the expansion of coconut in Saurashtra didn’t begin with any scheme.

“Here the farmers have done everything on their own. The government came later. The Coconut Development Board has only just opened an office,” he added. “In Saurashtra now, the best, the most remunerative crop is coconut. The quality of tender coconut water is the best in Gujarat. Better than South.”

Also Read: Gujarat is the hub of India’s potato revolution. Feeding the world frozen fries

Why coconut won out

As the sun sets into the Arabian Sea, Bhimsi Bhai and Dana Bhai sip on piping hot tea as trucks carrying fresh batches of coconut pass through Chanduvav village in Junagadh’s Patan Veraval Taluka.

Their profits for this quarter are taken care of and they can sit back and relax after a season of production. They once grew mostly groundnuts, urad dal, and wheat, but nothing has yielded more returns than the coconut.

Six months ago, Dana realised that the small patch of coconut on his six bighas was bringing in more income than the rest of his crops combined. He cleared the older crops and planted more coconut saplings. Coconut, he says, has not only raised his earnings but given him more time. He now has a two-storey house and a grocery shop. Toiling all day on the field is a thing of the past.

Currently more than 300 farmers are in queue for seedlings, and the waiting time is more than 1.5 years

-Naranbhai, coconut farmer

Many farmers across the coastal belt tell a similar story. According to horticulture officials, coconut has replaced 40-50 per cent of groundnut and wheat in the region.

Gujarat is no stranger to reinvention in agriculture and related sectors. Its Amul-led white revolution transformed milk production, the state became one of India’s biggest banana producers in the 2000s, and it’s the king of the country’s potato-processing industry. A common thread has been that farmers are quick to try new things, whether it’s ‘jungle model’ farming, using nano-fertilisers, or growing exotic fruits like dragonfruit (given the new identity of ‘kamalam’ by the state government) for international exports.

In comparison to traditional crops like wheat and groundnut, coconut is a winning combination of high returns and low maintenance.

“Compared to other crops it is easy,” said Bhimsi Bhai. “Once planted, we need to water it once a week or in fifteen days, use little fertiliser, and only do occasional cutting.” For farmers like him, average annual profits reach up to Rs 6 lakh.

Daily rush hour

At 5 in the evening, there is no hustle in the farms anymore. The rush has now shifted to roads and loading areas.

At Junagadh’s Gadu village, the intersection turns into a loading yard for coconuts. Trucks line up nose-to-tail. One heading to Jaipur, another to Delhi, another to Chandigarh.

Workers, about five to a truck, form chains, passing coconuts from hand to hand. One, two, three, they count until each truck fills its 25-tonne load. One loading is done in 20 minutes and then off the truck goes. One man scribbles in a notebook: number of pieces, destination, driver’s name.

The work starts at 3 pm here and ends at midnight. The whole five-kilometre radius smells of fresh coconut, earthy with a hint of sweetness.

“This is the off season of coconut, so there are only seven-eight trucks. During summer, I have loaded more than 60 trucks in a day,” said Raju Bhai, owner of Sidhhi Suppliers, one of the biggest suppliers of coconut in the market. With a notebook in hand and a pencil tucked behind his ear, he doesn’t have a minute to spare, his eye trained to spot any errant coconut rolling away.

“All the coconut people in Delhi have are sent by us,” he added. Someone calls out to him—a truck is leaving for Chandigarh—and he hurries away.

First coconut from Bengal dominated the market. But when there was infestation there, the traders shifted to Gujarat because it was cheaper

-Ashish Kapoor, Delhi-based trader

The best quality coconuts cost Rs 25 apiece now in the wholesale market, but in summer the price goes as high as Rs 60. Farmers get Rs 10-15 per nut, but transport eats most of the margin. On the retail front, a coconut in Delhi-NCR goes for Rs 80-100. Raju said he enjoyed a profit of more than Rs 10 lakh in the last year.

Trade in eastern coconuts has faded in north India, according to traders, and Gujarat is now filling that spot. It has an advantage over southern producers as well.

“Buyers in the north prefer to buy coconut from Gujarat because the transportation is cheaper than southern states, given the proximity of the state,” said Raju. “Since Covid, the market in the area has changed, I witnessed it myself.”

Even though the four South Indian states together account for about 91 per cent of India’s coconut production, Gujarat still has scope to widen its niche, according to ICAR-CPCRI director Hebbar.

“As of now, the major traders and entrepreneurs from the south have a robust trust-based distribution chain catering to the North Indian hubs. Having said that, if the production in Gujarat surges, the state certainly has a better logistical advantage in terms of supply chains towards the North and West Indian markets,” he said. “There are reports that 20 per cent of the total coconuts produced in Gujarat are harvested as tender coconuts. Though the data is not validated, this will certainly have a detrimental impact on the market share of tender coconuts from the southern states.”

Production is largely concentrated in seven coastal districts — Gir Somnath, Bhavnagar, Kutch, Valsad, Junagadh, Navsari and Dwarka — but former Coconut Development Board (CDB) officer Jayakumar says another 15,000 hectares could feasibly be brought under cultivation.

Where credit is due for the success story is still a matter of debate. Jayakumar says the big push began in 2013, when the CDB introduced a production improvement programme in Junagadh, held seminars, and helped set up farmer societies. The state agriculture minister, meanwhile, claimed that the coconut boom started when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was Gujarat CM. The state government now has a Gujarat Coconut Development Programme, which offers a 75 per cent subsidy on plantation costs to some 4,000 beneficiaries.

Farmers, however, argue it was their own gamble that turned the coast into a coconut belt, and that the government arrived late to the party.

How did it all start?

Some 20 years ago, Gujarat was nowhere on India’s coconut-growing map. It didn’t even figure in the Coconut Development Board’s production list for 2000-01.

But the following year, it registered its presence with 14,000 hectares under cultivation and 125 million nuts. Behind this leap were farmers like Naranbhai and Danabhai Solanki, who realised the commercial potential and began experimenting long before anyone in the state agriculture system paid attention.

In the early 2000s, a young Naranbhai, now in his forties, made a long and tedious car journey of over 1,600 kilometres from his village Supasi in Somnath to Kasargod in Kerala. He was on a mission to learn the coconut cultivation techniques Kerala had perfected and bring them home.

At the Central Plantation Crops Research Institute (CPCRI), he met farmers, spoke to scientists, took notes, and returned with a few saplings. He repeated the trip over the next few years, slowly expanding his orchard in Supasi. Within five years, he started making profits, and in the next decade, the number of farmers who joined him grew fivefold.

While entrepreneurial young farmers like him were waking up to new possibilities, scientists at the department of horticulture in the Junagadh Agricultural University were also experimenting with hybrids that could better adapt to Gujarat’s harsh climate.

Traditionally, Gujarat has the Lotan and Bona varieties of coconut but the Mahuva facility of the department, led by Varu, created two hybrids over the years, tall × dwarf, dwarf × tall. In Saurashtra, meanwhile, the Vanfer hybrid also became popular. These varieties are now increasingly sought after by farmers for their hardiness.

Early adopters like Naranbhai are now coconut influencers of sorts. As Naranbhai takes a stroll through the coconut field, his phone buzzes continuously with notifications on his WhatsApp groups: Coconut Farmer 1, Farmer 2, Farmer 3. The groups share updates on seedlings, varieties, and the daily rate—“big nut Rs 25, small nut Rs 15”—with farmers keeping the discussion going through the day.

Here the farmers have done everything on their own. The government came later. The Coconut Development Board has only just opened an office. In Saurashtra now, the best, the most remunerative crop is coconut

-DK Varu, dean of the College of Horticulture at Junagadh Agricultural University

Like a true blue businessman, Naranbhai keeps track of the KPIs of his trees. The hybrids are doing well. “This has given me around 200 nuts this month,” he said pointing to one.

But there is a problem now. Everyone now wants hybrids, but the state’s nurseries can produce only 15,000-20,000 seedlings a year, against a demand of more than five lakh.

In this situation, some farmers, including Naranbhai, have started raising hybrid seedlings at home in backyard nurseries. But he’s struggling to match demand too.

“Currently more than 300 farmers are in queue for seedlings, and the waiting time is more than 1.5 years,” said Naranbhai, still busy answering WhatsApp inquiries and tending to the online queue of those waiting for seedlings.

The main reason for the heightened clamour for hybrids is climate change. Slowly but surely, it is affecting the productivity of the traditional Loton variety.

Warning signs

Abundance is not a given when it comes to coconuts. It’s most evident in the coconut ‘crisis’ of Kerala, one of the largest producers. Coconut production has dropped by 40 per cent over the past year, and as prices rose, thefts were reported from groves and grocery stores. People shared memes of coconuts in bank lockers.

Much of the blame has gone to climate change and weevil attacks, as well as other stresses such as land being taken over for real estate development and labour shortages. In Tamil Nadu, cyclones such as Gaja also affected productivity, Hebbar said.

Gujarat is not immune either.

Coconut trees like heat and humidity, but rising temperatures along the coast have begun to bite. The Loton variety, which once gave farmers around 150 nuts a year, is now yielding only 80-100.

“The coconut production has increased in the area, but production per plant has decreased,” said Varu. Climate change, he added, was a major reason for the move away from groundnut too, with erratic rains pulling yields down year after year.

The coconut boom also opened the door to new problems.

As more farmers move to coconut and expand their orchards, many brought in seedlings from the southern states. With them came whiteflies — sap-sucking insects that have spread quickly across Saurashtra. They cause nuts to fall prematurely, and farmers say they are now forced to use more pesticides, which in turn has affected the honey bees that help pollinate the coconut trees.

Such is the impact that farmers are practicing artificial pollination in their households.

“We take the seed and pollinate it with the coconut variety,” said Naranbhai.

But overall, farmers are still buoyed by their prospects. They’re conquering the domestic market and now want more.

Also Read: Dalit women reclaiming Punjab’s farmlands. ‘We are born on this land, have a right to it’

Dreams of cracking exports

Trader Ashish Kapoor has been selling coconut in Delhi’s Azadpur mandi for 35 years. He has seen the Gujarat variety rise to the top over the last two years.

“First coconut from Bengal dominated the market. But when there was infestation there, the traders shifted to Gujarat because it was cheaper,” he said. The Karnataka variety is popular too — and his favourite because of its longer shelf life of a week compared to two days — but Gujarat coconut wins on price.

But Gujarat’s tender coconut advantage is yet to mature into export success.

India currently exports coconut to more than 140 countries, according to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, with export value crossing USD 393 million in 2021-22, up 41 per cent from the previous year. This includes oil, desiccated coconut, chips and other value-added products. Gujarat, however, has not caught up with its southern rivals on this front.

While Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu have built entire industries around coconut — oil, desiccated coconut, coir — Gujarat is still largely tied to tender coconut. There have been attempts to make by-products such as coco peat (the spongy husk material used in gardening), ice-cream sticks and brooms. But these are not big-ticket items that bring in large profits.

Back in Supasi village, Danabhai Solanki has expanded his orchard from 18 bighas to 30 bighas. That gamble has paid off so far, but he rues that exports have been a tough nut to crack.

“We want Adani and Ambani to invest in the coconut industry in Gujarat so that it can open doors of export opportunities for the state,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)