New Delhi: When Urban Company announced Insta Maids in March, promising domestic work delivered like groceries on BlinkIt, the name provoked righteous outrage. But for Rajeeva Reddy, a resident of an upscale Noida condominium, it signalled a new dawn.

“It’s just like the US, where the whole house can be cleaned for $20. The costs are so reasonable,” said the middle-aged Reddy. “We’ll no longer have to pay our maids when they go on holiday.”

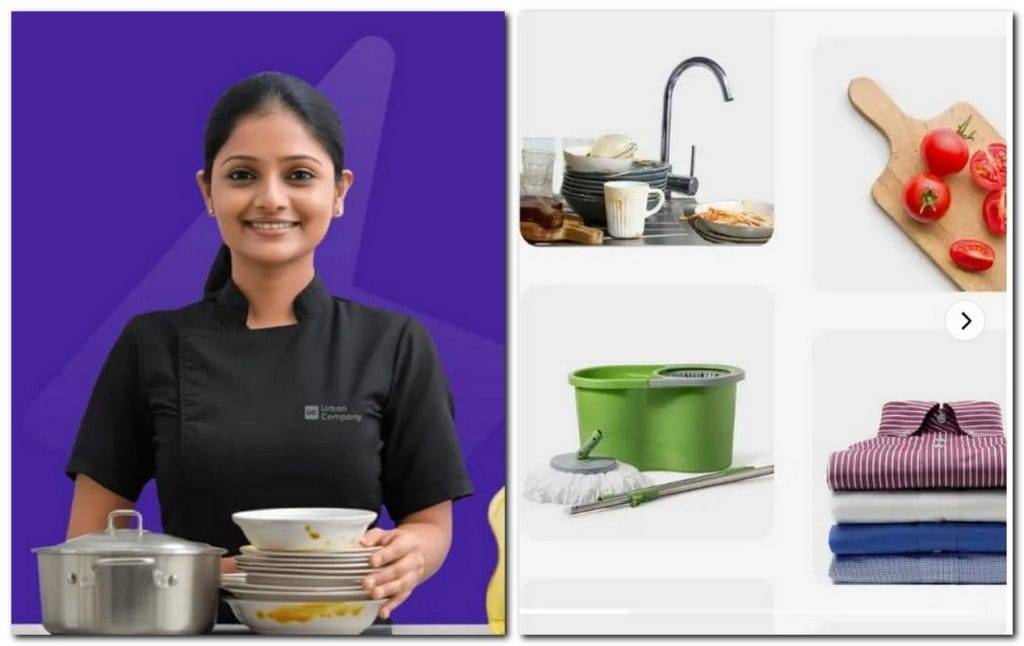

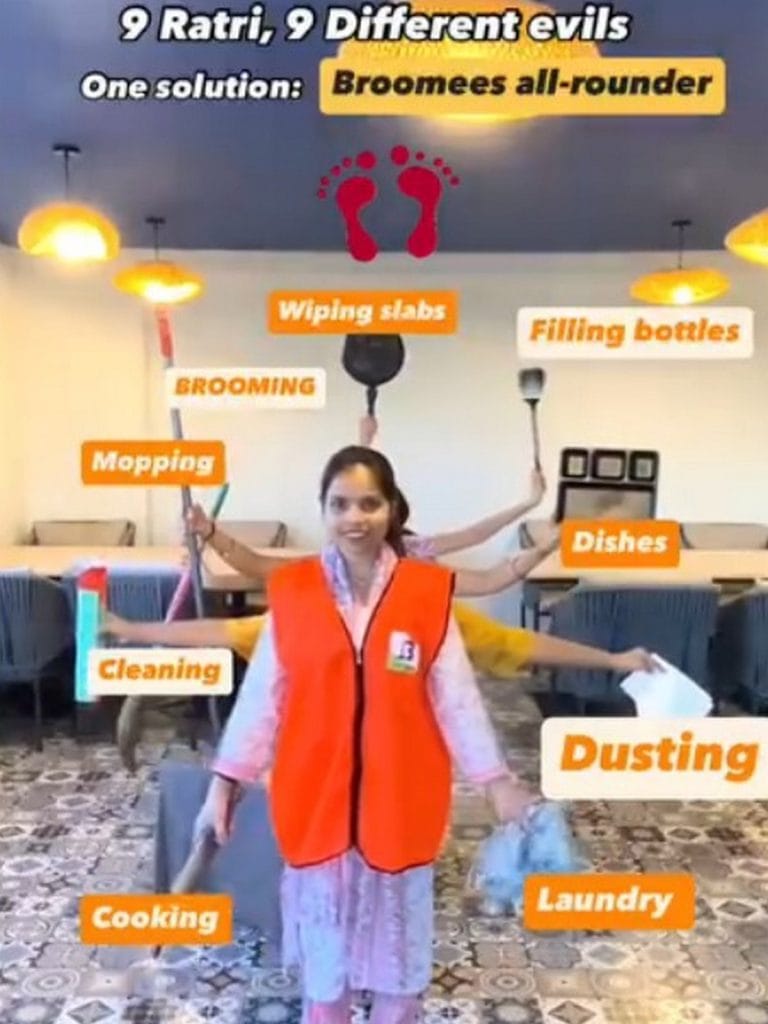

Now rebranded as Insta Help, the service is being piloted in parts of Mumbai. A slew of apps, most in nascent stages of development—Snabbit, Pronto, Broomees—are pledging to ‘disrupt’ what has always been an unorganised sector. But tech interventions in labour have typically privileged the customer over the worker, and the 15-minute model only deepens that imbalance. It’s adding another layer to what is already formless, further suspending workers in an unstructured no-man’s land.

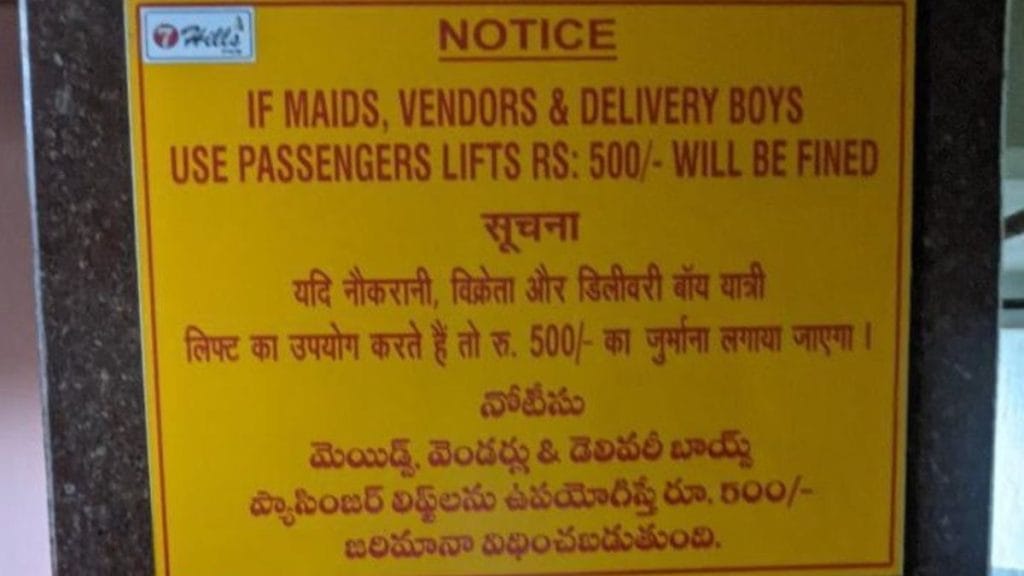

Domestic workers, the fulcrum of India’s enduring dependence culture, are the newest frontier of quick commerce. Tech is now cashing in on middle-class hypocrisy around the people who perform their domestic chores. Are they employees, family members, or just faceless labour after all? After instant delivery of potato chips to condoms, now it is domestic workers to clean floors, wash dishes, and dust corner shelves. Companies are building a market for instant, disposable labour.

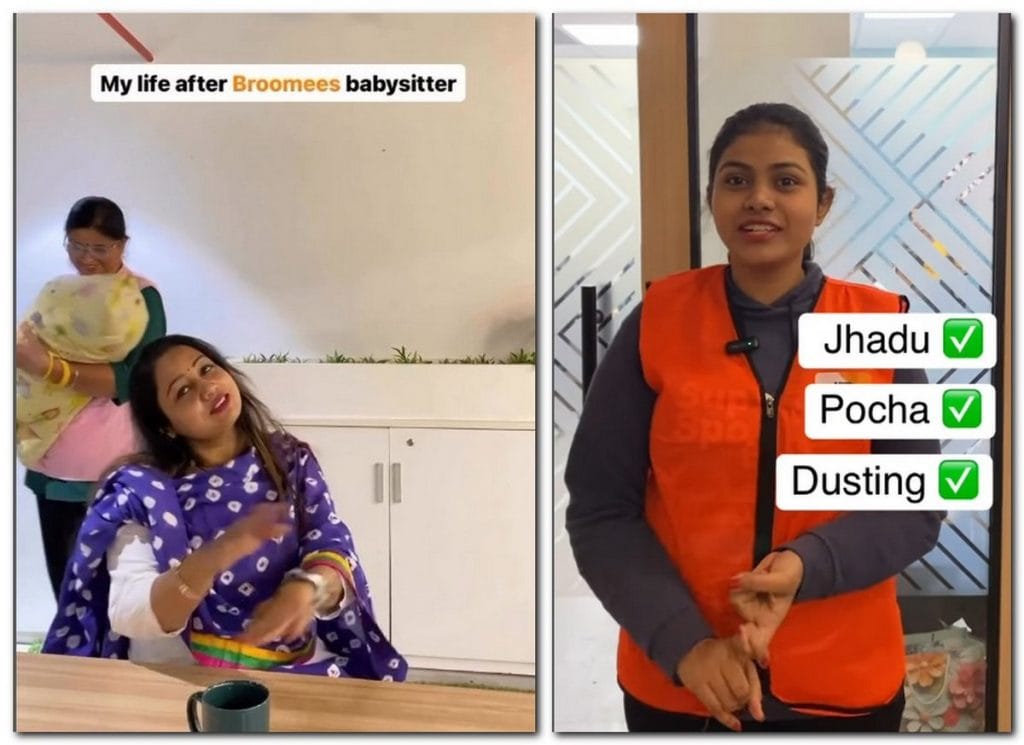

There’s a section of urban Indians who say they treat their domestic staff like family. They pay their children’s school fees, fund their medical bills, and employ generations of workers from the same family. Apps and agencies promise the opposite: ‘professionalising’ domestic work. It’s supposed to be a win-win that frees employers from the burden of personal responsibility and gives workers more autonomy, where they aren’t beholden to the whims of their employers.

But it’s not that simple. Domestic work is yet another space where deeply entrenched social and cultural biases dictate employment, be it caste or religion. ‘Disruptor’ apps were supposed to be the great equalisers, hacking away at prejudices by introducing a tech-mediated structure. Instead, they’ve either turned a blind eye—including to religious attacks—or actively reinforced biases such as BookMyBai, which allows users to filter by region and religion.

Once I start working, the expectation changes. (Customers) start asking me to clean their fans or bathrooms. That isn’t part of my job profile. But if I refuse, they complain to the app.

-BroomIt worker

A 2020 report by the Centre for Internet and Society warned that digital middlemen can further tip the scale in favour of employers rather than workers, widening inequalities.

The furore over Insta Maids was firmly restricted to the name. There was no indignation over the Rs 49 per hour offered to workers. Once the name was changed to the more politically correct Insta Help, internet armchair crusaders breathed a sigh of relief, and Urban Company issued a statement on how “words matter”.

Snabbit founder Aayush Agarwal, who previously worked for the quick-commerce company Zepto, is equally careful about words. Internally, his team calls workers “experts,” while to customers they are marketed as “trained househelps.” That, he says, instantly resonates with customers.

“Maids and gig are two words we do not use. That’s not the way we look at our workforce,” said Agarwal. “With grocery and food delivery, the product is what customers pay for while delivery is a means to the end. Here, without the service professional, there’s no business.”

The right packaging, whether it’s terminology or crisp uniforms, is an important part of the value proposition, according to Ambika Tandon, a tech and labour researcher pursuing her PhD at the University of Cambridge.

“They’re trying to cater to an upper-class imagination of what your service should look like by erasing any class, caste, or religious markers,” she said.

Quick service apps are catering to a dream, an aspirational future. They’re changing the optics of domestic workers, so the rich no longer have to confront the contrast between haves and have-nots in their own homes.

Also Read: Gurugram gate apps know everything. Privacy vs convenience is dividing condos

Less control, rest, and money

Each morning, a Broomees worker in her 30s puts on a fluorescent vest with the company’s logo, unsure of what the day will bring. Originally from Bihar, she’s been working with the company’s 15-minute vertical BroomIt for a month. So far, she says, she has less control over her time and work than when she was employed full-time by a Delhi family.

Her hours of work now vary depending on the day. The service, currently only available in South Delhi, lets customers choose from basic household tasks like sweeping or mopping on the app.

But when she arrives, customers often pile on more tasks.

“Once I start working, the expectation changes. They start asking me to clean their fans or bathrooms,” she said. “That isn’t part of my job profile. But if I refuse, they complain to the app.”

Most customers, she added, speak to her rudely and entitlement runs deep.

When she’s not assigned a job, she must wait for a booking at the Broomees headquarters in Okhla. She has to clock in by 8:30 am, and if she’s even 15 minutes late, half a day’s salary is cut.

Unlike Urban Company, where workers have some control over the jobs they book and the wages they ultimately receive, Broomees has a fixed salary. The Bihar worker is paid Rs 14,000 per month—well below the Delhi government’s minimum wage of Rs 18,456 for unskilled workers.

Anuradha, a 25-year-old Broomees worker, cooks for one household in the mornings and looks after another family’s children from 12 to 7 pm. She now earns between Rs 20,000 and Rs 25,000 a month, compared to the Rs 9,000–10,000 she made working for a family previously.

Snabbit workers can make up to Rs 40,000 per month, according to founder Agarwal.

For the BroomIt worker from Bihar, though, making ends meet is difficult. The sole earner in her Sarita Vihar home, she is considering pulling her 7-year-old daughter from school, as she no longer has the means to pay the fee. The family she worked for earlier provided food and lodging, but now that comes out of her salary. While Broomees offers optional health insurance, another worker told her the premium is deducted from the salary, so she doesn’t want to take it. The company does not pay for her commute.

In the traditional market, there are no social security benefits. There’s no access to loans, insurance, hygiene, and nor is there any standardisation in terms of leave. People were also reluctant to refer to themselves as helpers working in someone else’s home

-Niharika Jain, Broomees co-founder

When she goes to jobs, a male Broomees staffer drops her off for safety and also handles logistics like entering the OTP. She doesn’t know how much the customers pay for her services.

She took the job after her old employers moved elsewhere and she was struggling to find work.

“One of my friends received a phone call from Broomees, and I thought it’d be a good opportunity,” she said.

She went in blind, propelled by the prospect of stable employment. She didn’t anticipate the toll that it would take on the rest of her life.

Above all, she misses rest. As a 24-hour live-in worker, she was bound to one family, but once the day’s chores were done, she had time to herself.

Whether it’s an app as a mediator, or a family that’s tracking their every move, workers appear to be as powerless and devoid of agency as ever. It’s a reflection of how the last two decades of organising in different cities for their rights hasn’t made much progress.

“It’s double oppression. The worker has no idea of what the term conditions are. Actual bargaining power is limited,” said Shreya Ghosh of the Sangrami Gharelu Kamgar Union, an association of domestic workers. “Platforms and agencies hire workers, but the contracts are between the company and the person seeking the service.”

Experts often point to the priority given to customers in the gig economy, but the apps claim otherwise. Broomees calls itself a “worker-first” app. Urban Company, too, claims to have found a sweet spot that balances customer convenience with worker rights.

Sanitising domestic work

In Gurgaon’s plush high-rise communities, residents speak wistfully of India’s workforce becoming as ‘professional’ as in the West. The uniformed workers of quick service apps, summoned with a tap, match that aspiration, even though the model never quite took off there.

They’re coveting a system where the service is sacrosanct, and anything beyond it is excised. Urban Indian families have so far been accustomed to long-lasting ties with their domestic staff but now many prefer the idea of a quick transaction—no relationship, no conversation, no connection.

“The conventional method is getting on our nerves. Handling human beings long term is getting painful. We don’t want these headaches,” said Ritu Bhariok, a resident of DLF Phase 5. “What apps give you is peace of mind.”

She recalled an incident where a domestic worker alleged abuse and arrived with union members to protest at her condominium. That kind of disruption wasn’t what employers signed up for, added Bhariok, who is far more comfortable using apps.

“Our lives are getting stuck because of sweeping and mopping. It’s the same system in the corporate world as well—it’s cutthroat,” she said.

When a woman arrives on a bike, confidently dressed in uniform, she’s seen not as a regular help but a professional expert

-Aayush Agarwal, Snabbit founder

It’s this upper-class psyche that the apps have tapped into, as evident in their branding and marketing campaigns.

“Got vegetables in 10 minutes? Now get house help in 10 minutes,” reads a Snabbit ad on a Mumbai bus stand.

One of Urban Company’s first advertisements for what was then Insta Maids shows a woman, her brow furrowed in frustration. She’s just received a text message from ‘Sunita-maid’ which says: “Didi aaj nahi aaungi. Gaon jaana hai” (I will not be coming today. I have to go to the village).

Insta Help swoops in to save the day. “Your maid left you hanging? We’ll leave your home spotless,” the ad states.

Urban Company’s domestic work vertical is positioned as a last-minute solution—like BlinkIt, but for floors, dishes, and bathrooms.

All these quick service apps are catering to a dream, an aspirational future. They’re changing the optics of domestic workers, so the rich no longer have to confront the contrast between haves and have-nots in their own homes.

Women working with Snabbit wear pink polo t-shirts, trousers, and ride e-bikes.

“We’re changing lives, empowering women. When a woman arrives on a bike, confidently dressed in uniform, she’s seen not as a regular help but a professional expert,” said Agarwal. “The perception completely changes.”

Pronto, another such app still in “building mode,” uses animated images in its ads to represent workers doing chores—a sanitised, simulated version of domestic labour.

Noida’s Reddy said that his domestic staff have been with him for the past 10 years and that he “takes care” of their families, including paying for their children’s education. But he’s excited about a pivot.

“I haven’t been to a salon in a year. The gentleman comes over to my place. Similarly, this (Insta Help) is an interesting launch,” he said.

Scaling up, one city at a time

Apart from the slick branding, these companies are busy building extensive supply chains.

Broomees, for instance, has a recruitment centre in Jharkhand as well as a field team that traverses various jhuggis to land potential workers. The background check includes police verification, Aadhaar and KYC documents, and references from an ex-employer, family member, or neighbour. There’s also an in-house assessment to gauge soft skills. Currently, 96 per cent of Broomees’ 12,000 workers are women.

Agarwal began Snabbit as a “bootstrapped founder”, seeking out workers in “low-income areas”, explaining the model, and eventually training them in his living room.

“It was like making a sales pitch,” he said.

Insta Help is building a new pool from the “ground up”. Both companies conduct background checks and police verification.

Where companies choose to launch also matters.

“Platforms need to be hyperlocal to be able to function in India. Labour is so deeply embedded in local culture that it’s extremely difficult to understand the market,” said Ambika Tandon, a tech and labour researcher pursuing her PhD at the University of Cambridge.

Founded in 2021 and featured on Shark Tank India, Broomees first entered Bengaluru “because it was more organised,” said co-founder Niharika Jain.

For Snabbit and InstaHelp, the launch ground was Mumbai’s Powai. In start-up circles, it’s often conjectured that Urban Company rushed out Insta Help after Snabbit’s 2024 launch, backed by major VC players such as Nexus Ventures.

Urban Company, however, maintains that Mumbai was chosen because it’s an “economically cosmopolitan” environment.

“Mumbai provides a balanced mix across factors such as a household’s income levels, domicile status—migrants or long-term residents, family structure—nuclear or joint,” said the company in a statement to ThePrint, adding that on the supply side, they’ve always found talented professionals in the city.

For Agarwal, Powai was the obvious choice because he lived there and was grappling with the problem of ‘convenience’ that he’s trying to solve.

“It’s much easier to get a painter to paint your house than it is to get someone to clean your dishes,” he said.

Customer first, or worker first?

Experts often point to the priority given to customers in the gig economy, but the apps claim otherwise. Broomees calls itself a “worker-first” app. Urban Company, too, claims to have found a sweet spot that balances customer convenience with worker rights.

Each platform takes a slightly different approach to training and work conditions.

Insta Help workers go through a five-day programme covering digital literacy, soft skills, and time management. Once their training is complete, they receive a Skill India certificate, as well as the promise of ‘formal’ employment.

The conventional method is getting on our nerves. Handling human beings long term is getting painful. We don’t want these headaches. What apps give you is peace of mind

-Ritu Bhariok, Gurugram resident

Snabbit runs a “three-day boot camp”, according to Agarwal, where it’s also drilled into the workers that they aren’t ‘didis’ or ‘bais’.

Broomees’ Jain also points to the social benefits of working for a company rather than directly for a household.

“In the traditional market, there are no social security benefits. There’s no access to loans, insurance, hygiene, and nor is there any standardisation in terms of leave,” said Jain. “People were also reluctant to refer to themselves as helpers working in someone else’s home.”

Other than the quick-commerce vertical, Broomees also places workers in 12-hour and 24-hour jobs.

While this introduces new layers of structure, they don’t necessarily stop employers from becoming involved in their workers’ personal lives

“The intimacy stays. What we assure are the basics: three days leave per month and an hour of rest,” she Jain.

In a statement answering ThePrint’s questions, Urban Company said it was meeting a market gap while giving workers the chance to upskill.

“We, thus, see an opportunity to organise the space—ensuring smooth experience for our users and uplifting the livelihoods of our professionals,” said the company. “Today, there is a lot of friction for a consumer to arrange househelp, in case a need arises. In fact, the service experience is also not predictable. This overall results in a sub-par experience.”

But customers have frustrations of their own. It’s the luck of the draw.

A young mother in Noida who regularly uses app-based services said a worker sent by Broomees had “competency issues”. She also claimed the app encouraged the worker to quit, leaving her no choice but to renew her subscription.

Online platforms are also filled with negative reviews of the app, including one complaint that a designated worker was under 18 years old.

Jain responded that the Aadhaar card provided to the company showed the worker was over 18, and that’s the only metric that they can follow. She also noted that customers frequently bring unrealistic expectations about skill levels and language proficiency.

They’ve attempted to institute training programmes, but it’s a “cash-flow heavy project”.

Also Read: CEOs want us to work weekends without overtime. Don’t we ask the same of our cooks, cleaners?

Labour and bonds

Outside the gates of high-rise societies in Noida and Gurugram — the proverbial gilded towers — there are often groups of domestic workers, walking, chatting, or looking for work. The hiring process has traditionally been informal, passed along by word of mouth. There are no written agreements either.

“The contract is entirely verbal. And the general sense among unions and workers is that the sector cannot be platformised,” said Tandon, who is currently researching the Rajdhani tourist driver union.

According to her, Urban Company and similar platforms aren’t meeting an existing need but are creating the market itself. But she also acknowledges the flipside.

“Labour is cheap and population density is high. Quick commerce has done much better in India than in any other market,” said Tandon.

But the Broomees worker from Bihar says that if she had a choice, she would abandon the app entirely. The pressure is enormous, the money is too little, and she’s monitored constantly, leaving no time to look for another job.

“I can’t do any extra work. By the time I reach home, it’s 8:30 pm. It’s too late,” she said. “Whenever I raise an issue with a customer, they complain directly. They don’t say a word to me.”

Back in Noida, the young mother and employer says she’s using apps but would rather forge a relationship and generational ties with her domestic staff. Two generations of the same family worked in her home while she was growing up in the 1990s. One “looked after” her until she was married. But times have changed, she rued, and aspirations are different. The children of her staff don’t want to do domestic work.

“This generation wants to study, they don’t want to work. And Gen Z gets bored easily. They’re not indebted. They treat it like just another job,” she said. “The right person always wants to move.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

We only need condoms in 10 minutes. We don’t know when and where the opportunity will present itself.

The rest can take time. But condoms must be delivered in 10 minutes.