New Delhi: Six-year-old Rahul jumps off the wooden stairs leading to the judge’s dais. His sister Neha, who is five, stands on top of a wobbly bench. For four years, the family courtroom in Noida has been their personal playground every time their mother’s divorce case comes up for hearing. But without a children’s waiting room in the court, they make do with benches and stairs in place of toys while couples fight and lawyers bicker around them. Their playmates are police personnel, plaintiffs and judges.

Few family courts in India have safe spaces for children to wait while a case is being heard or to interact with a parent during custody battles. And though children are the “ultimate victims of a family feud”—an observation by the Kerala High Court—dedicated waiting rooms for them are still on the waitlist of things to be done.

Children—some younger than Rahul and Neha—are forced to spend hours in dreary courtrooms and corridors. It becomes an extension of their homes that have already turned into battlegrounds for their mums and dads. The Kerala High Court took up the issue last year, but was told that some family courts had “no space” for such rooms. Lack of space, especially in older buildings, is one of the main hurdles.

This week, the Supreme Court ordered a father to meet his child in a mall every Sunday and not the family court at Chavara village in Kerala. It noted that repeated visits to the court premises would also not be in the interest of the child. “…The environment during which the visitation rights are exercised would also matter.”

“In the absence of such rooms, it would not be possible to gauge and observe the non-verbally expressed wishes and welfare of a child. More importantly, in cases where there is alleged abuse or domestic violence or harassment, these rooms act as the only safe place to conduct visitations,” said Delhi High Court lawyer Ajunee Singh.

Family courts are theatres of adult emotions—from outpourings of grief and tears to anger. And in the crowded corridors and stuffy rooms, the children absorb it all. This compelled a mother in New Delhi, Richa Chadha, to start an online petition demanding that the children’s room at New Delhi’s Tis Hazari family court be upgraded. She had to take her five-year-old daughter to court to meet her father while the couple were fighting over the debris of their marriage.

With over 75,000 signatures, her petition continues to draw attention to the cause.

“It (the court visits) devastated her…people often ask, ‘What would such a young child understand?’ But you know, she remembers,” Chadha said.

Mickey Mouse and Tweety

The Noida court where Neha and Rahul play is in stark contrast to the children’s waiting room in New Delhi’s Patiala House court.

This room on the first floor of the family court building has bright red and blue walls, comfortable couches, an air conditioner and even a television. On one of the walls is a painting of a child holding her parent’s hand at a beach looking straight at what could be a sunrise or a sunset, with palm trees on both sides of the painting. A sand castle and the word ‘LOVE’ written in capital letters in the sky complete the painting.

Right in the middle of the room is a table with blue, red, green and pink chairs, and Mickey Mouse and Tweety toys.

Waiting rooms help facilitate a meaningful interaction between the child and the non-custodial parents, which is in the best interest of the child, said Rytim Vohra Ahuja

Children’s waiting rooms in family court complexes serve several purposes. They function as waiting spaces for children who visit the court with one of their parents who is usually engaged in a legal battle with the other parent. They also serve as safe spaces for them to interact with the parent who does not have interim custody of the child.

“It helps facilitate a meaningful interaction between the child and the non-custodial parent, which is in the best interest of the child and will uphold the intent of the statutes which govern child custody,” said Rytim Vohra Ahuja, an associate at Karanjawala and Co. law firm. Her practice often takes her to family courts in New Delhi.

Ready assistance and availability of child counsellors for children facing the choice between one parent over the other is also not uniform across districts.

But lawyers, judges and parents are increasingly demanding that this infrastructure be prioritised. Such dedicated spaces create a conducive environment for children to bond with the visiting parent. Singh also said that they serve as the “only secure, congenial and neutral venue for a court (through its counsellor) supervised visitation”.

Suffocating corners

Chadha realised that safe spaces for children were essential when she was fighting for custody of her daughter. She had to take her to the children’s room for court-mandated meetings with her husband. And what she found was a tiny, cheerless room. It was “small, compact and gives an unfamiliar ground for the children to spend that quality time with the parents,” she wrote in her petition.

There were about a dozen other children, along with their parents and grandparents, often hurling accusations at each other in front of them.

Chadha got married in November 2010 and had her daughter in 2012. Things between the couple soon began to fall apart and they started living separately in 2015. The same year began the litany of litigation between them, with allegations and counter-allegations leading to at least a dozen cases.

Looking back at that “traumatic chapter” in her life, she calls her brush with the judicial system a “bitter experience”. “The lawyers do not want to listen to you, they just want the parties to be in litigation,” said Chadha, who is now a Nguvu Change leader, backed by the Nguvu Collective, where she is part of a community with over 300 women change leaders who campaign on a range of gender justice issues.

In her change.org petition, filed in 2019, she describes the waiting room as suffocating. Chadha decided to settle the disputes with her husband and got a divorce in March 2020, but she continues to spread awareness about her online petition, which currently has 75,148 signatures, just halfway through its goal of 1.5 lakh signatures.

In 2021, she even visited the children’s rooms in all family courts in New Delhi, to draw a comparative analysis.

“They made me run a lot,” she said, adding that she was often given the “no space” argument to explain the insufficient children’s waiting rooms. She, however, told ThePrint that this year, the children’s room in Tis Hazari got an upgrade with wallpaper, water dispenser, new books and toys.

The lack of such spaces also exposes children to a horde of vulnerabilities, according to a family court judge in Uttar Pradesh, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. She said that when she calls couples in her chamber to speak to them privately, the children often accompany them—because there is no waiting room.

And children witness their parents sling accusations at each other. It leaves a long-lasting impact on the child’s mind, said the judge. For visitation meets, due to the lack of quiet spaces within the court premises, she resorts to ordering visits in public spaces like shopping malls and parks.

But that brings its own set of complications. For one, the court can no longer ensure compliance.

Children are being poisoned, even if passively, said the judge

“Most of the times when we order visitation at public places, there are allegations that the parent did not bring the child. Those things can be avoided [with waiting rooms],” said the judge.

If the parents get privacy, the children will also be protected from the vile courtroom drama.

“Because ultimately, the children are getting poisoned, even if passively,” the judge added.

Also read: Duties, duties, duties. Modi is going back to the Indira Gandhi Emergency era

Poisoning of children’s minds

Last June, Kerala-based advocate R Leela, who regularly appears before family courts, brought the issue to the attention of the Kerala High Court, highlighting the “pathetic condition” of the family courts in the state.

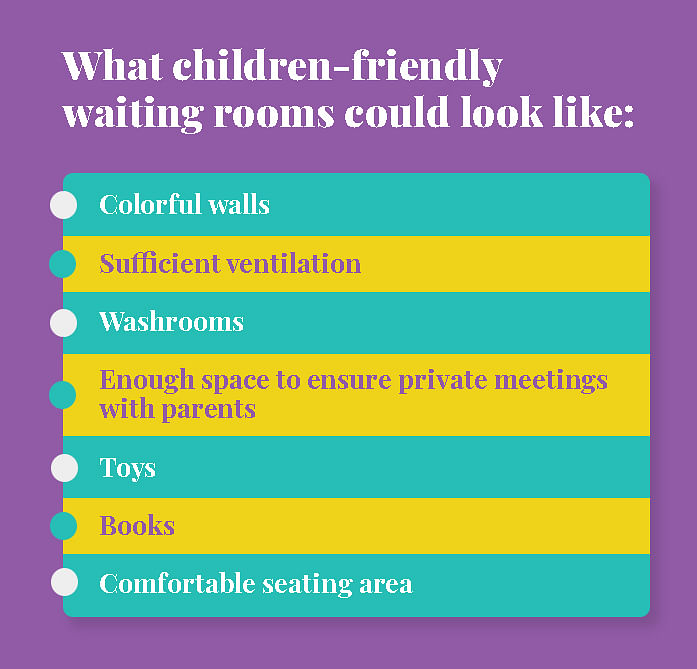

She highlighted a range of issues, from the lack of waiting rooms altogether, to waiting rooms that lack ventilation or even proper space for parents to interact with children.

In a short but scathing order, Justice A Muhamed Mustaque spoke of the lack of a waiting room for children.

The court noted that most of the family courts in Kerala function on leased premises without adequate infrastructure and facilities.

“In a few family courts, the children and the parties are seen standing in jam-packed corridors and even on the roads for the whole day. The congested courts and the over-crowded premises, in fact, stares at the young minds, who develop negative notions regarding the justice delivery system in the country,” the judge said.

The court noted that unlike family courts, Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) courts have dedicated spaces for children. The judge then demanded a report from the Registrar (District Judiciary) about exploring the possibility of dedicating a separate room in all the family courts with a child-friendly atmosphere somewhat akin to the POCSO courts.

Children who never made a choice to be born to fighting parens are being dragged to courts, said R Leela

Leela highlighted the issue of the huge pendency of cases in family courts across the country. She said that “this (dispute) is basically between a family or the relationship between the husband and wife, with children who never made a choice to be born to such fighting parents being dragged into the courts”.

She explained that it is acknowledged under international law as well as the juvenile justice law in India that children are not to be exposed to courts or uniformed police officers. “But children have to come before the court despite their non-interest, see the lawyers, the judges, and express their opinion that is often imparted in their mind by their fighting parent who has their custody,” she said.

The POCSO Act 2012 makes several exceptions to ensure that children are shielded from the criminal justice system. For instance, the law says that the statements of minor victims should be recorded at their residences. And while recording the child’s statement, the police officer shall not be in uniform.

Also read: ‘Blatantly erroneous’ — how 56 death sentences in 14 months defied latest Supreme Court guidelines

Lack of space

After the Kerala High Court’s June 2022 order, the Registrar General submitted a report in the court on 21 July last year. The court was informed that the family courts in seven districts had a readily available room to allow parents to exercise their custody or visitation rights. It was also told that a separate room can be made available after the construction of new buildings in five other districts.

However, the high court ran into the oft-cited hurdle of lack of infrastructure for such a room in a few courts. It was told that the family courts at Attingal, Nedumangad, Thiruvalla, Thodupuzha, Ernakulam, Ottapalam and Thalassery had no space for a separate room for children. The court, therefore, deferred the proposal for providing an independent room in these courts for the time being.

Leela told ThePrint that a space was subsequently made available in Ernakulam for children, with Tom and Jerry and other cartoons drawn on the walls. However, she said that this room “is not sufficiently ventilated and it does not have a bathroom”. Apart from this, she said that the lawyers and judges in family courts are making earnest efforts to bring in more facilities.

She also highlighted insufficiencies in several courts across Kerala. For instance, in Adoor, she said that an old age home has been converted into a family court, in an isolated area. The second floor of this court remains unoccupied, and therefore, “if anything happens there, nobody will be able to undo the damage”. In North Paravur family court, she said that the children’s room is “pathetic”— smaller than 100 sq ft, with all the children sitting together on a bed. Leela added that the room does not have any place for the parents to sit, and the room is full of trash.

“Efforts are being made. Unless and until, there is cooperation from the bar as well as the bench, child-friendly rooms cannot be created,” she said.

In March this year, the Kerala High Court noted that the family court in Kozhikode had started a dedicated room for children, at the initiative of the bar association of Kozhikode. It, therefore, added the Bar Council of Kerala as a respondent before it to coordinate with the concerned bar associations in establishing child-friendly rooms.

Also read: Husband not paying maintenance despite court order? HC says civil suit can be filed for arrears

For love and affection

When home becomes a warzone, the children often become casualties of it. Leela said that the welfare of the children is a paramount consideration for courts.

Both parents are fighting for the child, neither of them is actually thinking about the child, said R Leela

“What I have seen is when both the parents are fighting for the child, neither of them is actually thinking about the child…They actually use the children as chattel, or property, through which they can gain some benefit,” she added.

It’s important to have counsellors for children. And though every family court does have counsellors, Leela insists that it’s not enough.

“Child counsellors, who can understand the feelings of the child, are able to bring the parents to the understanding that they shouldn’t be treating the children as chattel…that is what is lacking in family court matters,” Leela said.

Ahuja said that in her experience, she has not seen family courts take assistance from counsellors to help children. She has, however, seen high courts refer such cases to child psychologists, and hopes that the practice will permeate into family courts too.

“When custody is directly in question before the court, children are more often than not tutored to think negatively about the non-custodial parent. As a result, the child gets alienated from that parent. Counsellors play a pivotal role in bridging this gap and ensuring a meaningful equation between the non-custodial parent and child,” she said.

This, she said, would ensure enforcement of judgments that have time and again reiterated that “love and affection of both parents is essential for the welfare of the child”.

It’s left to the judge’s discretion to decide if a child needs counselling, but experts say it should be the norm.

Children are tutored to answer in specific ways to the judges, said Ajunee Singh

Singh said that she has seen the engagement of counsellors often by the court in such cases. According to her, in custody battles, the judges often interact with the children to ascertain their wishes. However, this poses several hurdles. For instance, the children sometimes do not open up to the judges in “rather intimate settings”, Singh said.

She also spoke of children being “tutored to answer in specific ways to the judges”.

“Court counsellors have repeated and regulated interactions with children, by way of which they can form a fit psychological opinion as well as assess the true wishes of the child, without the tutoring,” she said.

Combined with a congenial environment, it’s possible for children to be comfortable in court premises.

“Under the aegis of a court counsellor or child psychologist, these waiting rooms are crucial in serving as pseudo judicial centres for child support,” she added.

The Kerala High Court also directed counsellors in family courts to “impart effective counselling to children in matters pertaining to custody/visitation/guardianship of children”. This was after the court noted that “no effective counselling” was being given to the children.

“Therefore, we are of the view that the counsellors of family courts have to be directed to impart effective counselling to children, to make them understand about the litigation between their warring parents/guardians which would in some way obviate the heart-burn of the children,” the court asserted.

Tale of two mothers

I never brought my children to court, said Sunita

A government school teacher in Noida, Sunita (32)* finds it more comfortable to collect the maintenance amount from her estranged husband every month in court.

“But I never brought my children to the court,” she said, with her eyes on a constant search for her husband in the swarm of men thronging the corridors of the court. She feels safer to meet him within judicial premises.

Sunita leaves her children at her mother’s house, where she moved in after several instances of physical violence in her marriage.

“They (judges) often want both the parents…So there is a deep psychological impact on the children,” she said, waiting outside the courtroom.

Meanwhile, inside the same courtroom, Rahul and Neha continue to play. Their mother, Savitri* got married when she was “17 or 18 years old”. She does not have the family support to leave the children in someone’s care when she visits the courtroom. She demanded a divorce after two years of a marriage that was plagued with violence and her husband’s drug problem.

Waiting with their mother, Rahul spins a coin, turning it into a spinning toy, and then kicks his blue slippers toward the wall, right past the imaginary goalkeeper in his make-believe football ground. Noticing judgmental stares from those around her prompted Savitri to rebuke Rahul, “You’re embarrassing me, do you know where we are?”

“Court,” he said shyly.

*Names have been changed either on request of the participants or to protect the identities of parties in family disputes.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)