New Delhi: Financial consultant Abhay Chandalia is in the throes of a massive spring-cleaning exercise at his office in South Extension II, New Delhi. Hundreds of thick files cover the couches, chairs, and tables as he briskly directs his staff. Over 400 files have already been shredded, making way for the hundreds of new clients who bring physical share certificates to his firm, Share Samadhan, every month.

Locked up in rusting cupboards or wedged between old school marksheets, these paper shares were bought decades ago, when companies issued physical certificates. Today, they hold no value until they are converted into electronic (dematerialised) form. This has been the case ever since the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) banned the transfer of physical shares from 1 April 2019, with a few exceptions.

But the lengthy and convoluted process has birthed a new business fuelled by desperation and frustration. It’s given rise to financial consultants like Chandalia, who bring not just expertise in cutting through red tape and connections in government departments, but something many clients lack— time and patience. His firm gets over a thousand inquiries every month, from transferring shares after a shareholder’s death, to processing claims with the government’s Investor Education and Protection Fund Authority (IEPFA), to dematerialising physical shares.

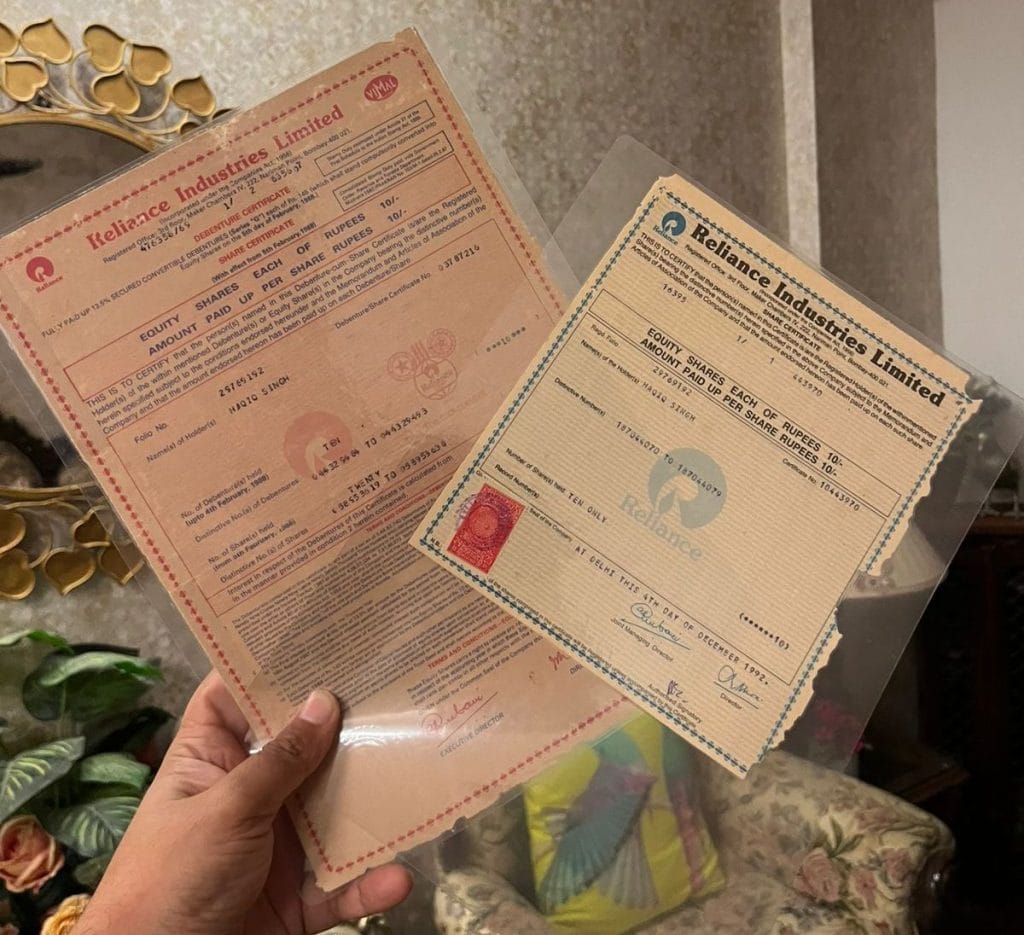

“My maternal grandfather had shares of Reliance Industries Limited that he bought in 1992. They were stacked with my mother’s graduation certificates,” said Rattan Dhillon, from Ram Singhwala, Punjab, who works in the auto industry. He found the shares while shifting houses. “I didn’t know the process so I asked my followers on X. Some told me to preserve them since the shares had Dhirubhai Ambani’s original signature.”

We found these at home, but I have no idea about the stock market. Can someone with expertise guide us on whether we still own these shares??@reliancegroup pic.twitter.com/KO8EKpbjD3

— Rattan Dhillon (@ShivrattanDhil1) March 11, 2025

After Dhillon’s post went viral on 11 March, hundreds of people commented seeking advice about their own certificates. Bought by parents or deceased family members in the 1980s and 1990s, these shares had been lying dormant in their homes. Many had begun the frantic process of dematerialising and reclaiming the assets, but were stymied by complex paperwork, contradictory instructions, and long timelines.

The most common bottleneck, according to three industry experts who spoke with ThePrint, lies with the Investor Education and Protection Fund (IEPF), administered by the IEPFA under the Ministry of Corporate Affairs. Companies are required to transfer shares and unpaid dividends to the fund if they remain unclaimed for seven years or more. Physical share certificates that have not been dematerialised also fall under this category.

“They (IEPFA) don’t want to release any money, they just want to eat more,” alleged Harsh Roongta, founder of Fee Only Investment Advisors, a Mumbai-based advisory firm registered with SEBI. “They never even disclose the total value of the shares they hold.”

For a deceased family member who owned the shares, you have to prove your entitlement. Succession laws can be complicated. If your grandfather died, the legal heirs are his mother, spouse, and children. IEPF or RTAs may ask you for his mother’s death certificate. Most of your family members may not even be aware of her name.

-Harsh Roongta, founder of Fee Only Investment Advisors

On 31 July 2023, a response in the Lok Sabha revealed that IEPF held unclaimed assets worth Rs 5,714 crore. But Roongta and his team estimated that as of September 2024, IEPF’s shareholding in listed companies was Rs 84,393 crore—about 15 times the number reported in Parliament.

“We worked this out by going to the shareholding pattern of all listed companies, finding out how many shares are held by IEPF and then valuing it as per market rates,” said Roongta, who published the data on his company’s website. “That is the extent of the opacity that surrounds this issue.”

ThePrint emailed a set of questions to the IEFPA but did not receive a response. However, on 18 April, the IEPFA published a video interview with their Deputy Director, Gaurav Gupta, on their YouTube channel in an attempt to clear the air.

“Under the Companies Act, the companies are duty-bound to tell the investors (about unclaimed funds) and provide them an opportunity of three months before transferring any shares or dividend to the authority,” said Gupta. “This is done in the form of a public notice and providing the information on the website of the respective companies.”

He went on to add that the IEPFA also has a search facility on its website, where investors can check whether any assets they own have been transferred by the company to the fund. Gupta also highlighted that the IEPFA was upgrading its IT infrastructure to provide faster services to stakeholders.

“There may be misconceptions that getting the services from IEPFA is time-consuming or elaborate,” said Gupta. “If you provide the documentation which will help us and the company to establish your entitlement, I think that this process can be DIY (do it yourself) mode.”

Under the video, one user commented about waiting a year and a half for an approval. Another complained about not being able to get in touch with the government body through the contact section of the website.

Confronted with delays and dead ends, more people are seeking help from consultants like Chandalia’s Share Samadhan. The firm was one of the first to turn solving this labyrinthine process into an organised business.

“Agencies know how much you have in unclaimed shares even before you do,” said Akshay Naik, project director at Money Life Foundation, a non-profit advocating financial literacy. “They know the process inside out, have their own database and contacts with IEPF and MCA. For someone new to the process, it will be very difficult.”

A mismatched signature, a misspelled name, or a missing death certificate can lead to people either giving up completely on the process, or turning to private consultancies for help.

Also Read: ‘Mujhe EMI bharna hai’—how voice tech is bringing millions of Indians into banking system

Untangling the paper trail

When Jinesh Mathew first stumbled upon his father’s old SBI shares in May 2021, he had no idea that dematerialising them would become a months-long exercise in bureaucracy and patience.

The shares had been lying dormant since the late 1990s. His father had purchased State Bank of Travancore shares during the Initial Public Offering (IPO), at a time when SBI’s regional branches were still independent entities.

“I was not familiar with the stock market until November 2020,” said the 33-year-old software engineer from Aranmula, Kerala. “So it was a completely new process for me, and not a lot of people I turned to could give me any guidance.”

Three times I had to visit the RTA. First for the name change, second for the signature, and third when we finally got the shares dematerialised, It should all be completely digitised. Rather than going to an office, we should be able to scan everything and send it across.

-Jinesh Mathew

Jinesh works in Thiruvananthapuram, so it was relatively easy for him to visit the Registrar and Transfer Agent (RTA) office in person. These are private organisations employed by publicly listed companies to maintain and update investor records. Although documents can be sent remotely, he said meeting the team face to face helped speed up the digitisation process.

But then came the first major roadblock, which appeared to be a minor discrepancy.

“The shares were jointly held by my mother and father. There was a name mismatch,” he said, explaining that his mother’s official documents carried her father’s name, while the shares listed her husband’s. “I had to get an affidavit signed by a notary, confirming her identity. But then we got a letter from the RTA stating there was a signature mismatch.”

Navigating the formalities meant multiple visits to the stockbroker and RTA. Affidavits had to be drawn up and notarised, email exchanges ran into double digits, and all of this unfolded in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Three times I had to visit the RTA. First for the name change, second for the signature, and third when we finally got the shares dematerialised,” said Jinesh. “It should all be completely digitised. Rather than going to an office, we should be able to scan everything and send it across.”

While Jinesh hunkered down and managed the dematerialisation process himself, many people simply give up because of the knowledge gap and how long it takes.

Forty-eight-year-old Anish Babbar from Abohar, Punjab, tried to claim his brother’s shares after he died, but spent three-and-a-half years running from IEPFA pillar to post. He spoke to the company secretary, RTA, and brokers but had no luck.

“They [RTAs] continuously harass you, don’t answer your questions properly or give you the right information,” said Babbar, adding that he travelled to Mumbai personally to hand over the relevant documents to the RTA. “They kept stringing me along saying they will get it done by next weekend, then two days, then six days.”

Frustrated by the slow and complicated process, Babbar turned to Share Samadhan for help.

“The work we do is in legal compliance. You can do it yourself, or we will guide you on what to do,” said Chandalia. Companies have investor sections on their websites that provide all the steps and documents can be submitted directly, but as he puts it, “challenges arise”.

Chandalia added that it’s the back-and-forth between the shareholder, the company’s RTA, and the IEPF that wastes time. A mismatched signature, a misspelled name, or a missing death certificate can lead to people either giving up completely on the process, or turning to firms like Share Samadhan.

“You are saving your time and buying my time,” said Chandalia, adding that “mental peace” is a benefit that comes with signing up for his services. “We are consultants, subject matter experts. And for this, we charge a commission.”

Commissions vary depending on the consultant, but Chandalia charges anywhere between 10-12 per cent of the share value. There have been cases where he charged up to 20 per cent, but those days are behind him. Competitors, recognising the business opportunity, have sprouted across the country, driving down commission rates.

“We follow a seven-step process to evaluate whether we can take on a client,” said Chandalia, proudly displaying a PowerPoint slide deck with the steps. After the initial sales call, the team examines a client’s documents, checks feasibility and timelines, and finally sends across a proposal.

While IEPF did put out a document a few years ago, asking for suggestions to streamline the process, nothing seems to have come of it.

The business of unclaimed shares

At the Share Samadhan office, sales consultants are busy on the phone, working through the unique predicaments of clients. The company also helps with mutual fund redemptions and provident fund recovery, but the bulk of its work revolves around physical shares, which it claims has a potential market size of Rs 3,78,000 crore.

“We currently have 1,200 active client mandates. About 60-70 per cent of the mandates fall under IEPF claims,” said Chandalia.

Sometimes a deceased parent owned the shares; other times, certificates were lost in transit. Legal heirs have to jump through hoops to prove their entitlement. There’s no fixed path to dematerialisation, or to transfer ownership if required.

“It’s a multi-layered problem,” said Roongta, explaining that it all starts with who owns the shares, and whether they’re still alive. “The least complicated part is if you are the owner of the shares, they haven’t been transferred to IEPF, and they just need to be dematerialised.”

For dematerialisation, a demat account with a SEBI-registered depository participant (DP) is required. These could be banks (like SBI, HDFC), stockbrokers (such as Zerodha or Groww), or financial institutions like Life Insurance Corporation (LIC).

After filling out a dematerialisation request form and submitting it with the original share certificates, the DP forwards the documents to the company’s RTA for verification. The shares are credited to the demat account after an approval process that can take up to four weeks.

The process is similar for people who have lost their physical shares, or have been issued bonus shares that are missing. They just need to prove themselves as the rightful owners by updating their KYC (Know Your Customer) with the RTA.

When shares are transferred to IEPF, an entirely different process is followed—what Roongta jokingly calls “another mother.” For living shareholders, an entitlement letter from the RTA is required to claim the shares from IEPF. But if the shareholder is deceased, an additional mountain of documents is required: death certificates, succession proof, notarised affidavits.

“For a deceased family member who owned the shares, you have to prove your entitlement,” said Roongta. “Succession laws can be complicated. If your grandfather died, the legal heirs are his mother, spouse, and children. IEPF or RTAs may ask you for his mother’s death certificate. Most of your family members may not even be aware of her name.”

For Roongta, the problem lies in misaligned incentives.

“(RTAs) are not getting paid more for successful claims,” said Roongta, adding that the incentive for them to reunite shares with the rightful owners doesn’t exist. “But if there is an adverse claim—and there are fraudsters out there—then they get pulled up.”

Chandalia recalled one case where the son of a former Solicitor General of India approached Share Samadhan to claim an uncle’s shares.

“He had been trying to retrieve those shares for the last 15–20 years,” said Chandalia, noting just how long some people, irrespective of status, have to wait to get their shares from IEPF. “I charged him 20 per cent, but I got it done.”

Also Read: Let’s talk about red tape, cash flow, say Indian startup founders

Calls for reform

When Dhillon’s post gained traction online, he received direct messages from both RIL’s RTA, KFin Technologies Limited, and the IEPF. It motivated him to start the claim process and assured him of their cooperation. This was IEPF’s chance to set an example for others.

The fund told Dhillon they could get the claim done in four to six months, which was a much shorter timeframe than the two to five years he’d heard about in online forums. After submitting the relevant documents to the RTA, including the legal heir certificate, Dhillon got a call from a senior executive at IEPF.

“They told me they would fast-track my case as someone from the ministry was pushing for it,” said Dhillon, acknowledging that his situation wasn’t the norm. “Most people have a problem with IEPF because they take a long time to respond.”

Dhillon told the IEPF that they should set up a dedicated helpline and email address for consumer queries. But Roongta says that the primary function of the agency needs to change altogether.

“The name itself is wrong. Why should an investor education and protection fund be in charge of unclaimed properties?” he said. According to him, there should be a central authority solely focused on reuniting unclaimed properties with their rightful owners.

And he’s not the only one calling for change–not when there’s at least Rs 5,700 crore at stake.

“Rather than helping find the rightful owners of the shares, they have just been sitting on it,” said Akshay Naik of Money Life Foundation. While IEPF did put out a document a few years ago, asking for suggestions to streamline the process, nothing seems to have come of it.

“I don’t think anything changed after that. And their corpus keeps growing.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)