A small shrine in Dugri near Ludhiana marks the place where singer Amar Singh Chamkila was born to an impoverished Dalit Sikh family on 20 July 1960. Laminated newspaper clippings and photographs of the singer and his wife Amarjot Kaur flicker in the flame of a diya lit by an elderly caretaker. Located next to a garbage unloading space, the shrine is easy to miss. But every year on 8 March, the area is transformed into a mela—hundreds of singers, performers and villagers gather to remember Chamkila and Amarjot who were assassinated in 1988 at the peak of the militant separatist insurgency in Punjab.

Chamkila is everywhere in Punjab — in road-side dhabas, trucks, weddings, and homes. His first recorded song, ‘Takue Te Takua’ is still all the rage especially in villages, and local musicians put up photos of him and call him ‘guru’. Now, Imtiaz Ali’s Netflix biopic Chamkila, starring Diljit Dosanjh and Parineeti Chopra, has initiated a resurgence of interest in the singer. “Our records are being sold in black, like the tickets of Amitabh Bachchan’s films are,” says Chamkila in Imtiaz’s film, which was released on 11 April.

The ‘Elvis of Punjab’, who could command massive crowds with the sheer power of his voice and lyrics was 27 when he was killed. He wrote, composed and sang songs on Jatt pride, the plight of farm workers, alcohol, dowry, domestic violence and drug abuse in feudal Punjab. He told stories that were real, flawed and relatable. His allure was such that even the Jat Sikhs embraced his songs.

Many considered his songs to be vulgar, lewd. In ‘Lalkara’, he sings about a woman accepting her addiction to her lover. ‘Maar le hor try jija’ is about a woman urging her brother-in-law to have a child with her after he discovers that his own wife cannot bear children. ‘Driver Rokk Gaddi’ was another popular song about a truck driver from Punjab falling in love with a girl from Uttar Pradesh. The girl calls the driver a player, and asks him to come back to her, for the sake of their son. These were taboo subjects in a Punjab that was under the thumb of separatists who dictated how people lived. But people defied diktats such as not more than five people should accompany a baraat, for Chamkila.

Everyone says he sang vulgar songs, but they were songs about reality, the village life. I would say the songs today are vulgar. Can you even sit together as a family and watch these songs together?

— Surinder Singh, former sarpanch of the village Mehsampur where they were assassinated

They turned up hordes to watch him and Amarjot perform — women atop terraces, and men and children filling fields in akhadas. And he commanded their attention with just a mic and a tumbi, along with accompanying dholak and harmonium players.

Fifteen days after he and Amarjot were shot dead, militants assassinated the revolutionary poet Pash. And in December that year, popular actor Veerendra Singh (Dharmendra’s cousin) was murdered.

“Everyone says he sang vulgar songs, but they were songs about reality, the village life. I would say the songs today are vulgar. Can you even sit together as a family and watch these songs together?” said Surinder Singh, former sarpanch of the village Mehsampur where they were assassinated.

Also read: Dalit housing, Ambedkar Gram to UPSC hubs. Are Mayawati’s legacies surviving in UP today?

The village where he was murdered

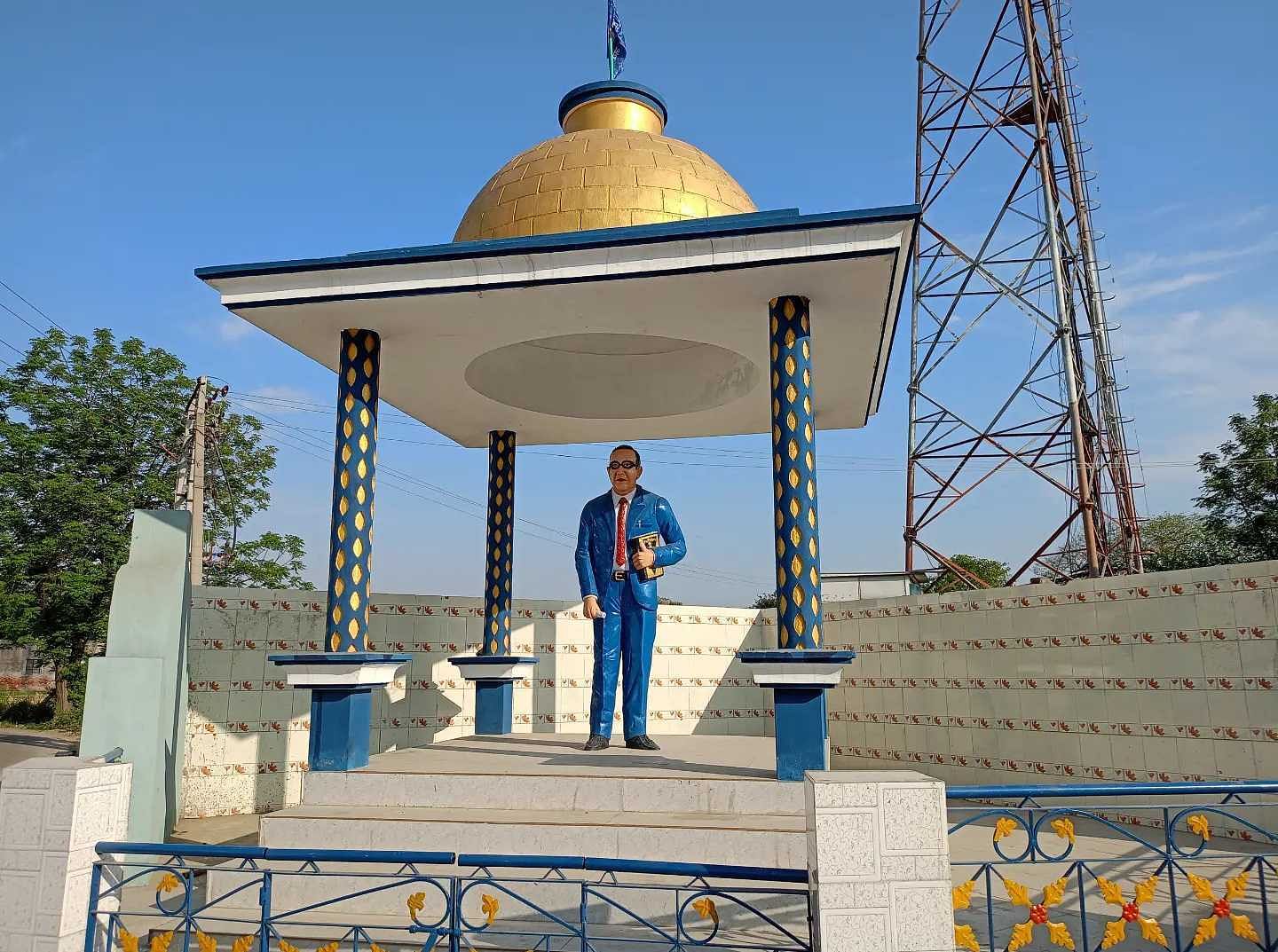

A large statue of Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar stands opposite the gurudwara at Mehsampur village, just an hour away from Ludhiana. Villagers are used to showing directors, journalists, influencers, fans and YouTubers around.

“This is the spot where it happened,” says one local guide. “This is the house where Chamkila had his last meal, where he had complained that the dal was cold,” says another villager.

The fields around the village are filled with ripening crops of wheat. Rose bushes bloom outside every other house. But there is an undercurrent of bitterness, regret — Mehsampur has the reputation of being a killing field.

On 8 March 1988, around 11 am, Chamkila and Amarjot started out from Ludhiana in an Ambassador car. They had been booked by a family in the village to perform for a wedding.

“I was 15, and till then, had only heard Chamkila’s songs. I was dressed up to go watch him, and was waiting eagerly. The village was anyway decked up for the wedding that was to take place,” said Singh. He never got to watch the performance.

The band reached Mehsampur at 2pm, as per the FIR lodged at Nurmahal police station.

After finishing their lunch, they headed to the akhada set up for the performance. Chamkila stepped out first, followed by Amarjot, even as eager onlookers and fans cheered at the arrival of the star.

Everyone missed the three men in turbans on a scooter — their faces shrouded in cloth —carrying guns. And then they started shooting. Within minutes, stunned villagers started screaming and running through fields to save themselves. The halwai was making jalebis, and frying pakoras when people burst into the space, running helter-skelter, trying to get as far away as possible from the three men who had just shot down Chamkila and Amarjot. The kadhai upturned, splashing hot oil on everyone, adding to the tragedy.

Four people died that day, including Chamkila and Amarjot. Band member Lal Chand, dropped his dholak and fled after being shot in his thigh.

When the three assailants left and the panic subsided, all that remained were dead bodies, blood and a village whose identity was changed forever. Makkhan Singh, was one of the four people who carried Chamkila’s body on a trolley, all the way to Phillaur, a distance of 10 kms.

“Everyone was still in shock for months. No one would gather out of fear, and the black day is all they could talk about,” added the sarpanch.

According to villagers, the family that had invited Chamkila and Amarjot blamed themselves for this. Many held them responsible as well.

“The family left soon after. There was a lot of badnami/slander. They could not stay on here and had to migrate to Canada,” said Singh.

Also read: Villagers use Saraswati riverbed for cow dung, cremation, crop. ‘Where do we keep cattle?’

In Punjab’s popular culture

It is a testimony to the sheer popularity of the singer that filmmakers have been drawn irresistibly to the heady concoction his life story provides — the underdog narrative, the songs, his background, the stories about him leaving his first wife for Amarjot, and the death threats.

In the biopic, Diljit’s Chamkila turns to an Income Tax department official Swaran Sivia for help when he starts getting letters commanding him to stop singing ‘vulgar’ songs. Their solution was to produce a devotional album.

“He wanted me to see if those letters were true or if someone was trying to fool him,” Sivia said, in an interview on the YouTube channel RPD 24. “He showed me all the threatening letters. One was from Bhindranwale Tiger Force which was signed by Rashpal Singh Chandra. The other letters were from Khalistan Commando Force and Khalistan Liberation Force.” Sivia, who was the songwriter for the devotional album, set up a meeting ‘Kharku Singhs’ at the Golden Temple.

“Chamkila folded his hands and apologised. He said I have made a huge mistake, please forgive me. They said you apologise to God and then speak to us,” he recalled the meeting.

The Netflix film is not the first to delve into the legend of Chamkila. Movie director Kabir Singh Chowdhry and writer Akshay Singh spent a year researching Chamkila’s killers, but the producers wanted a story on the singer himself. So, they decided to make Mehsampur (2018), a 98-minute movie that mashes together elements of a documentary, fiction and biopic, about the people trying to ‘crack’ the Chamkila story. They even convinced Chamkila’s dholak player Lal Chand, and the woman he used to sing with before Amarjot, Surendra Sonia, to play themselves in the film.

It was a coming together of fiction, reality and the legend of Chamkila, that adds to the almost surreal quality of the film, heightened by actual footage sequences, dark lighting.

“I remember when we were shooting, the double harvesters were at work in the fields of Mehsampur, and they were playing Chamkila’s songs, and it felt like a full circle,” says Chowdhry.

The film premiered at the 2018 Sydney International Film Festival, and won the Grand Jury Award at the 2018 MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Image) festival. It also won the Best Sound Design at Mosaic International South Asian Film Festival and the Best Editing at Diorama International Film Festival in 2019.

In 2022, actor-director Deepa Rai released the Punjabi film 22 Chamkila Forever, which was followed by Jodi (2023), another Punjabi-language romantic movie based on the love story between Chamkila and Amarjot. Incidentally, Diljit was cast as the singer, Amar Singh Sitaara. Sony Liv’s Chamak (2023) is a fictional take on Chamkila’s son returning to solve the mystery of his parents’ death, and a commentary on Punjab’s music industry.

Chamkila never faded from popular imagination, and that’s also because there is no closure. None of his killers were arrested. The case remains unsolved.

Also read: India’s tech bros’ new fad is Indic AI — Krutrim to AppsForBharat. The answer to ChatGPT

Earthy appeal, controversial lyrics

Chamkila was the music industry before the Punjab music industry became the multi-million-dollar enterprise that it is now. But before he became Chamkila, he was Dhani Ram, who had a passion for music but worked in a hosiery factory in Ludhiana.

The story goes that he impressed renowned Punjabi folk singer, Surinder Shinda, while working as a helper for one of their performances. Shinda recognised his talent, and inducted him into his troupe. But it was when he partnered with singer Surinder Sonia, that he became a star. While Shinde was away on a solo tour in Canada, Sonia and Dhani Ram recorded the album, ‘Takuye Te Takua Khadke’. It was a hit, and Amar Singh Chamkila was born.

“Sonia’s house at Ludhiana’s Model Town used to be the meeting point of Chamkila and the other singers. There would be soirees (majlish) with a constant flurry of at least 50 people in the beginning of the 1980s,” said Meena Soni, daughter-in-law of Surendar Sonia.

There was an earthy appeal to Chamkila’s songs.

That’s why theories abound as to why and who killed Chamkila. Some say that it was because he overreached by marrying Amarjot who was from a higher Ramgharia caste. Others say that it was a hit ordered by a rival musician who was frustrated that people only wanted to listen to Chamkila.

“He was barely a literate, but he had a way of constructing the narrative, representing, and depicting social relationships at the base level, beyond stereotypical norms. Especially lower-middle class, between bhaiya bhabhi, and was a sharp focused voice of social criticism,” said Jagrup Sekhon, professor at the political science department of Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar.

Even now, Chamkila’s songs are equally popular on Spotify, with more than 4 lakh monthly listeners, as are his grainy performance videos, uploaded on YouTube by VCR makers of the 80s. In his death, his popularity just expanded exponentially.

What brought Chamkila popularity also brought him envy and death threats. “Spiritual leaders were also upset with him as were separatists.

“But he had gone to appease both, and even met the Sikh militant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale at the Golden Temple,” says Sekhon.

That’s why theories abound as to why and who killed Chamkila. Some say that it was because he overreached by marrying Amarjot who was from a higher Ramgharia caste. Others say that it was a hit ordered by a rival musician who was frustrated that people only wanted to listen to Chamkila. Or it was a faction of separatists not commanded by Bhindranwale.

Thirty-six years later, neither Imtiaz’s film nor the academics or intellectuals or even police have any answer. For a brief moment in time, before he was silenced, Chamikila bedazzled Punjab.

With his biopic, Imtiaz Ali introduces Chamkila to a new generation of Indians unfamiliar with Punjab’s insurgent period. Kabir Singh Chowdhry wants to ride this wave, and start work on his next production, Laal Pari. It will be a theatrical performance.

“It’s going to be about one of the three killers, who is still alive. I spent time with him before making Mehsampur.”