Muzaffarpur: The Patna Medical College and Hospital stands as one of Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s most ambitious political promises in the upcoming Bihar assembly polls. It is soon going to be India’s largest government hospital with 5,462 beds. Its two gleaming towers now rise against the skyline near the Ganges, representing a Rs 5,540 crore transformation.

Yet, when it mattered most, it failed.

On 31 May at 1 pm, a 10-year-old rape survivor arrived at PMCH, tied to an oxygen cylinder, fighting for her life. For nearly four and a half agonising hours, she was shuffled between departments, left waiting in an ambulance under the relentless sun. The child had already endured a week of unimaginable cruelty.

It took scores of Congress party workers staging a protest before she was finally admitted, not to an ENT Intensive Care Unit (ICU), but to a gynaecology ward.

Hospitals and rapes—two long-standing crises in Bihar—are now converging to form a formidable political storm against Nitish Kumar in what may be his most precarious election year yet. His platform of good governance, once his strongest credential, began to fray years ago. Today, it threatens to completely unravel. The Dalit girl’s death highlights a twin problem–doctors and police have responded by setting up ad-hoc emergency rooms and resorting to bulldosing the home of accused rapist, respectively.

“The 2010 election was the last time Bihar’s voters voted on the basis of past performance rather than future promises,” said a retired IPS officer

According to NCRB data, in 2021, Bihar recorded 17,950 crimes against women, a 16.8 per cent increase from 2020. The state ranked second in dowry-related deaths with 1,000 cases, trailing only Uttar Pradesh. Kidnappings surged, with 6,589 incidents reported.

Yet, the conviction rate remains dismal—out of 18,517 trials in 2022, only 5,067 led to convictions, while 12,086 accused walked free.

“Crime isn’t always about statistics; it’s also about perception. When a state effectively curbs violent crimes, it also shapes the narrative surrounding law and order,” said Abhayanand, retired IPS officer and former DGP of Bihar.

“The 2010 election was the last time Bihar’s voters voted on the basis of past performance rather than future promises. Since 2015, Bihar has not seen an election of that kind,” he said, adding that the perception of Bihar’s law and order has deteriorated over the years.

On the night between 31 May and 1 June, the 10-year-old child fought desperately, clinging to the hope of life at the PMCH. In the early morning hours, around 5 am, her mother rushed out of the ward when she vomited blood. By 8:30 am, she was gone.

She regained consciousness once, around 10 am, but never again.

This is the RG Kar and Nirbhaya case of Bihar.

“What is the point of building these facilities if a poor woman must return home without her child?” asked Urmila Devi, the 30-year-old mother, now lying semi-conscious in a hut in their Muzaffarpur village.

In Gaya, the brutality extended beyond the victims. Dr. Jitendra Yadav, a doctor who treated the mother of a gang-rape survivor, was dragged out of his home, tied to a tree, and beaten mercilessly with iron rods and sticks in the first week of June. The police booked 10 persons linked to the accused. The survivor’s family claimed that the assault was retaliation for their testimony in court.

Amid this, yet another case emerged from Muzaffarpur district’s Turki Police Station, the rape survivor was 11-years-old and the accused remained absconding. This time, the state police’s response was quick—bulldozing the accused’s house on 5 June to force his surrender.

These cases have sparked outrage in Bihar with opposition leaders Tejashwi Yadav and Rahul Gandhi leading the charge against the government’s inaction. The political mobilisation has brought the issues of women’s safety and hospital negligence to the forefront of poll campaigns.

It has also led to unprecedented action—a speedy Forensic Science Laboratory (FSL) report arriving within a week, bypassing the usual six-month to one-year wait; the suspension of two hospital heads, Dr. Kumari Bibha and Dr. Abhijeet Singh (SKMCH and PMCH); the arrest of the accused; an inquiry launched by the health department; and daily follow-ups in the press. All this happened after pressure built on the state government in the first week of June.

The state also promised to set up a triage room for emergency cases, staffed with orthopaedic, gynaecology, medicine, and surgery doctors, ensuring that no patient is left waiting under the scorching sun again.

For the grieving family, such a response was unheard of and unimaginable too.

“It’s a rare follow-up,” said the 10-year-old’s uncle, Nagendra Paswan, pointing to political mobilisation as a major reason.

Bihar minister Kedar Gupta announced a Rs 4 lakh compensation for the victim’s family, promising immediate relief. He assured that a chargesheet would be filed within 10 days and the state would seek the death penalty against the accused within two months.

The first installment of compensation—Rs 4 lakh—has already been deposited into Urmila’s bank account. In addition, a lifetime pension of Rs 7,700 per month has been approved, with the first payment credited.

Hunting the rapist

“At midnight, when the child was at SKMCH, the FIR was finally lodged,” said the rape victim’s uncle.

Toddy tapper Ravi Paswan and Urmila Devi’s daughter was a happy-go-lucky child, as her two elder brothers, aged 12 and 15, fondly recalled.

After Ravi died in 2021, both sons of Urmila dropped out of school and had to earn a living—one at a tent house and the other at a construction site. Urmila still dreamt about sending her daughter to school.

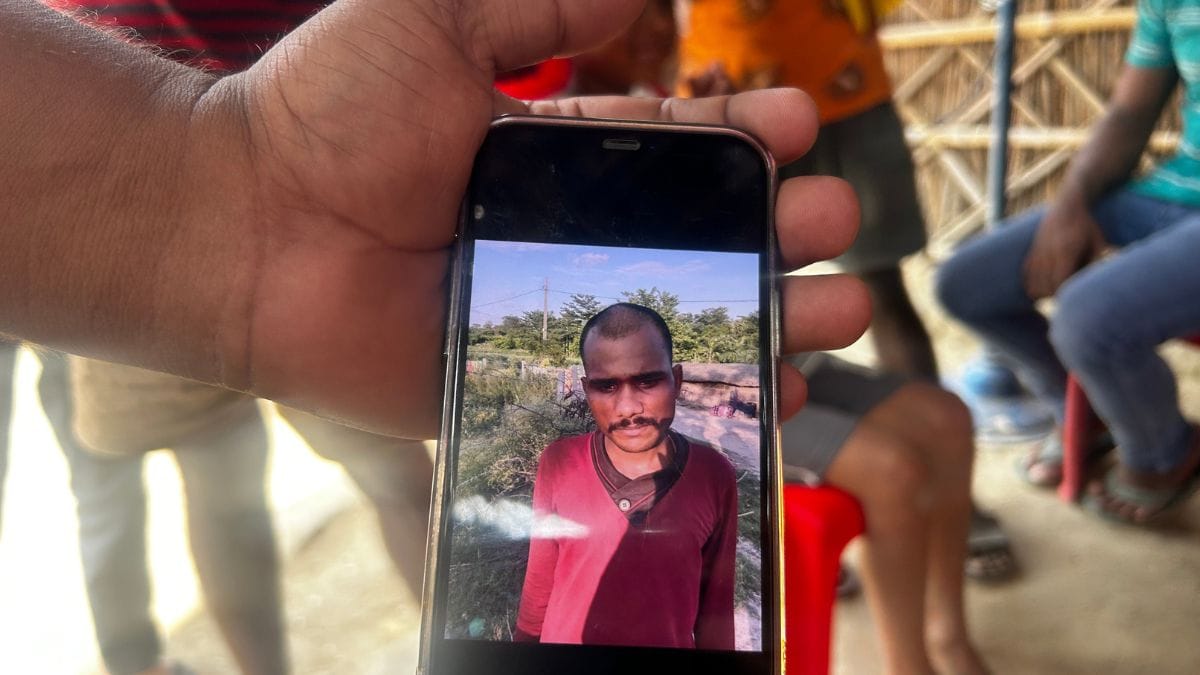

On 26 May, the daughter was allegedly abducted by a familiar fish seller from the neighbourhood village, Rohit Sahni, when she was playing in the courtyard. Luring her with chocolates and chips, he reportedly took her away on his bicycle.

Hours later, Urmila discovered her daughter missing.

She alerted the entire village, and soon, a frantic search began.

The villagers looked everywhere—her favourite play spots, her aunt’s house, where a ring ceremony was supposed to take place. But she was nowhere to be found.

Finally, a villager recalled that he had likely seen the fish seller, Sahni, taking the child away. The villagers stormed Harpur Balra, the neighbouring village, and found him.

“He blatantly refused to tell us anything,” recalled the child’s uncle, Nagendra.

A call to 112 was made, and soon, officers from the Kurhani police station arrived.

At 7 pm, nearly two kilometres away, deep in the maize fields surrounded by brick kilns, a JCB driver stopped abruptly as he saw a brutally injured girl lying on the roadside—naked, her throat slit, her chest ripped open.

She had crawled 150 meters from the maize fields, dragging herself to the roadside, waiting to be found.

“They (the police) were reluctant to confront Sahni at first, even when there were eyewitnesses who saw him taking the child away. The manhunt was launched by us. At midnight, when the child was at SKMCH, the FIR was finally lodged,” claimed Nagendra.

The villagers took it upon themselves to document the crime scene, recording videos and collecting evidence. Among the recovered items were the girl’s slippers, clothes, and a blade.

“Just two days before this incident, he attempted to assault another girl,” said Muzaffarpur SP.

The accused, Sahni, after injuring her, allegedly left her to die. He then shaved his beard and reportedly went to the police station to report a missing mobile phone miles away in Sonepur, announcing to the officers that he had come from there.

During the investigation, the police discovered that the accused had a history of harassing young girls.

“Just two days before this incident, he attempted to assault another girl. Nobody reported that case to the police,” Muzaffarpur Rural Superintendent of Police (SP) Vidya Sagar said.

Urmila’s daughter was rushed to Sri Krishna Medical College and Hospital (SKMCH) after being referred by the CHC.

She survived until 31 May. Though she had lost her voice, she narrated the horror through gestures—to her family, to the police.

“She asked for juice, for water,” her elder brother recounted. Now, the family is left with the painful image of the child writhing in pain on the bed during her final days.

SKMCH, with its temporary arrangements, admitted that she needed a life-saving surgery at a better, bigger facility.

An Advanced Life Support ambulance was arranged to take her to Patna.

“The way she fought for life gave me hope that she would survive,” her mother said.

The SHO of Kurhani police station, under whose jurisdiction the case falls, assured that the police would fast-track the case.

“The Director General of Police and the Superintendent of Police are personally overseeing the case. We have collected all the evidence, which will help us secure a conviction,” Ravi Prakash, SHO, told ThePrint.

The Paswan family, though frustrated by delays in police action on 26 May and treatment at SKMCH, held onto hope as the child was still alive. But at PMCH, their faith in the healthcare system broke, minute by minute, as the oxygen keeping her alive began to run out.

“We even begged them, warning that she would soon run out of oxygen. Still, someone asked us to pay Rs 2,500,” claimed Nagendra.

Currently, the investigation is at a crucial stage as the police have recovered the victim’s locket from the accused’s pocket.

Opposition’s protest

Since 1 June, the streets of Muzaffarpur and Patna have become a battleground for justice. Candle marches and sit-in protests have been carried out in outrage over the rape case, with roads being blocked.

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of India has taken suo motu cognizance of the case and issued notices to Bihar’s Chief Secretary and Director General of Police, demanding a detailed report within two weeks.

Currently, the political storm over Bihar’s healthcare system, intensified by the rape case, is far from settled.

“The allegations of a delay in getting a hospital bed are baseless,” said the PMCH chief.

Congress party workers have been continuously demanding the resignation of Health Minister Mangal Pandey, holding him responsible for PMCH’s medical negligence.

Pandey’s tenure has come under intense fire from opposition parties, as Bihar’s hospitals continue to make headlines for shocking cases of neglect and mismanagement.

Not long ago, the Nalanda Medical College and Hospital (NMCH), Bihar’s second-largest government hospital, became the centre of a disturbing controversy.

Awadhesh Prasad, a diabetic neuropathy patient, woke up in the hospital to find that rats had gnawed off his toes.

Before that, another patient, already deceased, had one of his eyes stolen from the hospital mortuary. Both incidents led to the suspension of junior medical staff.

Tejashwi Yadav has also levelled corruption allegations against Health Minister Mangal Pandey and the state government.

“Construction projects worth Rs 5,000 crore are underway at PMCH. The facility’s head (Dr IS Thakur) was shielded to cover up large-scale corruption in these projects,” he alleged.

Prashant Kishore’s Jan Suraj has now joined the movement, staging demonstrations in Gardanibagh, Patna. Posters reading “Sarkar soti rahi, betiyan roti rahi (government kept sleeping, daughters kept crying) ” were pasted across public walls.

“When the victim had arrived, instead of admitting her, they shuttled her between wards—sometimes citing a lack of beds, other times claiming the ICU was occupied,” Bihar Congress state president Rajesh Ram, who started agitations outside PMCH, said.

He also alleged that an air ambulance was requested from hospital staffers, but it was never arranged.

The state government and the PMCH both have denied allegations of negligence. Aas reported by the BBC, the PMCH chief IS Thakur, said that the girl was sent to the gynaecology department because the hospital doesn’t have an ENT ICU. And that Advanced Life Support ambulance (in which the survivor was brought in) already offers critical care.

“The allegations of a delay in getting a hospital bed are baseless,” Thakur said.

Meanwhile, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi took to Twitter, amplifying the demand for justice.

Back in Muzaffarpur village, the girl’s family home has become a hub for political gatherings. A blue tent, furnished with red plastic chairs, stands beside the huts, welcoming leaders who arrive with their entourages. Some bring cash assistance, offering amounts ranging from Rs 10,000 to Rs 20,000.

So far, Deputy Chief Minister Vijay Kumar Sinha, Tejashwi Yadav, and Chirag Paswan have visited the grieving family. Deputy CM Samrat Chaudhary has also promised that the case will be fast-tracked and justice will be served.

For now, the government is constructing a house for Urmila’s family under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY). The Zila Parishad is finally building them a toilet.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)