New Delhi: In the snug wooden hall of Akshara Theatre, director Anasuya Vaidya carefully arranges a bed, chairs, and telephone on stage, preparing for a performance of Agatha Christie’s The Patient. Pointing to the handmade wooden louvre AC unit, she proudly proclaims that every inch of this Connaught Place theatre is hand-crafted from wood.

Akshara Theatre is a tiny treasure from another world in Delhi’s performance landscape. While the city’s heart has some unchanged Soviet-era cultural landmarks, like the Kamani Auditorium, Shri Ram Centre, and Little Theatre Group (LTG), Akshara stands out as more of a labour of love than a commercial space.

The auditorium, a small, intimate 96-seater wood-panelled space, continues to be a much-loved space among the wider theatre community, even as many production houses move to larger, more modern venues. With cheaper tickets and a limited audience, it remains the go-to venue for many smaller theatre groups in the city. It has a unique boutique value.

As the second-generation co-founder and director of Akshara Theatre, 65-year-old Anusuya Vaidya continues to run it as her late parents—playwright Gopal Sharman and thespian Jalabala Vaidya—envisioned it: a blend of classical Indian culture and modern theatrical expression. For her, the theatre is more than a space; it’s her parents’ life’s work.

“My father has built this place with his own hands. I am not exaggerating. His love, sweat, and tears are imbued in this theatre,” said Vaidya, a faraway look in her kohl-lined eyes as she sat on a gleaming wooden chair in the dimly lit theatre, moments before rehearsal.

Akshara Theatre, founded in 1972 and later registered as a non-profit, has been the launchpad for many big names. Comedian Zakir Khan, and actors like Pankaj Tripathi, Sandeep Mahajan, and Varun Grover, all started here.

For small theatre groups, Akshara is a crucial space for their existence and survival. We need at least 10 theatres like Akshara

-Kuljeet Singh, creative director at Atelier Theatre

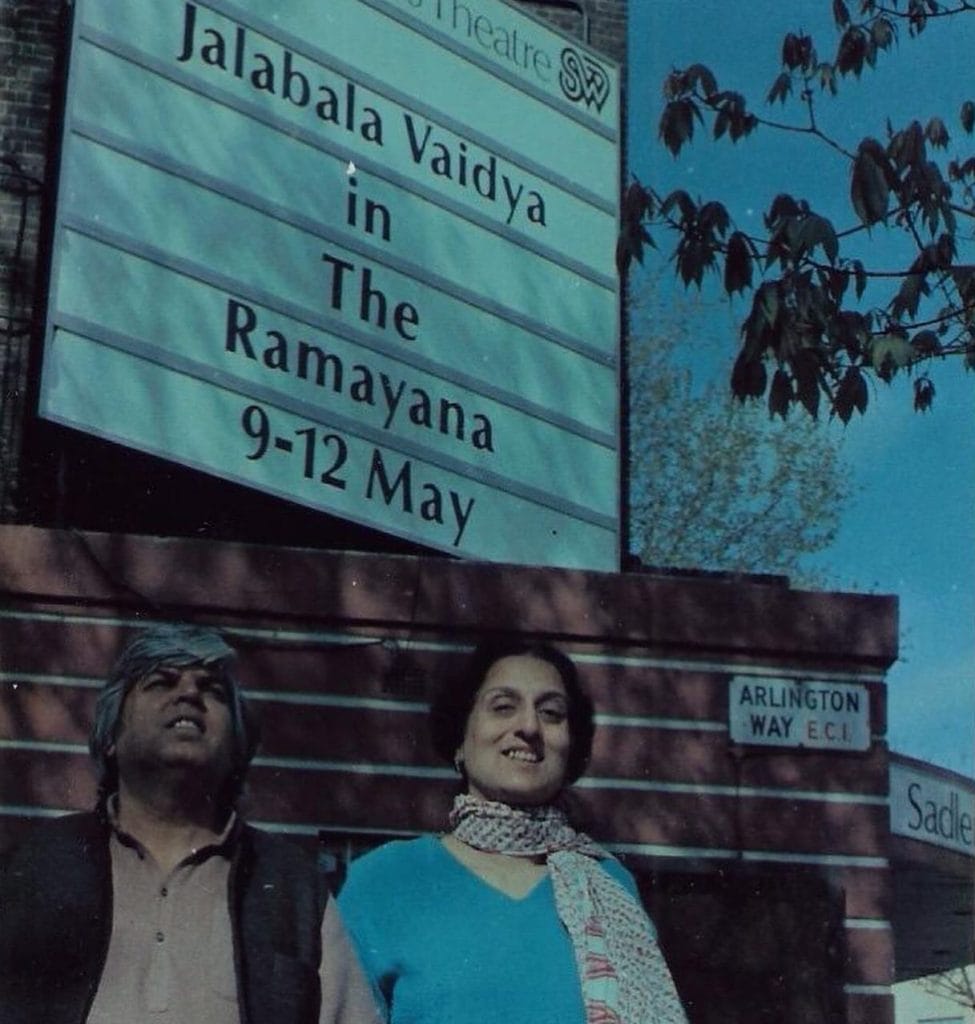

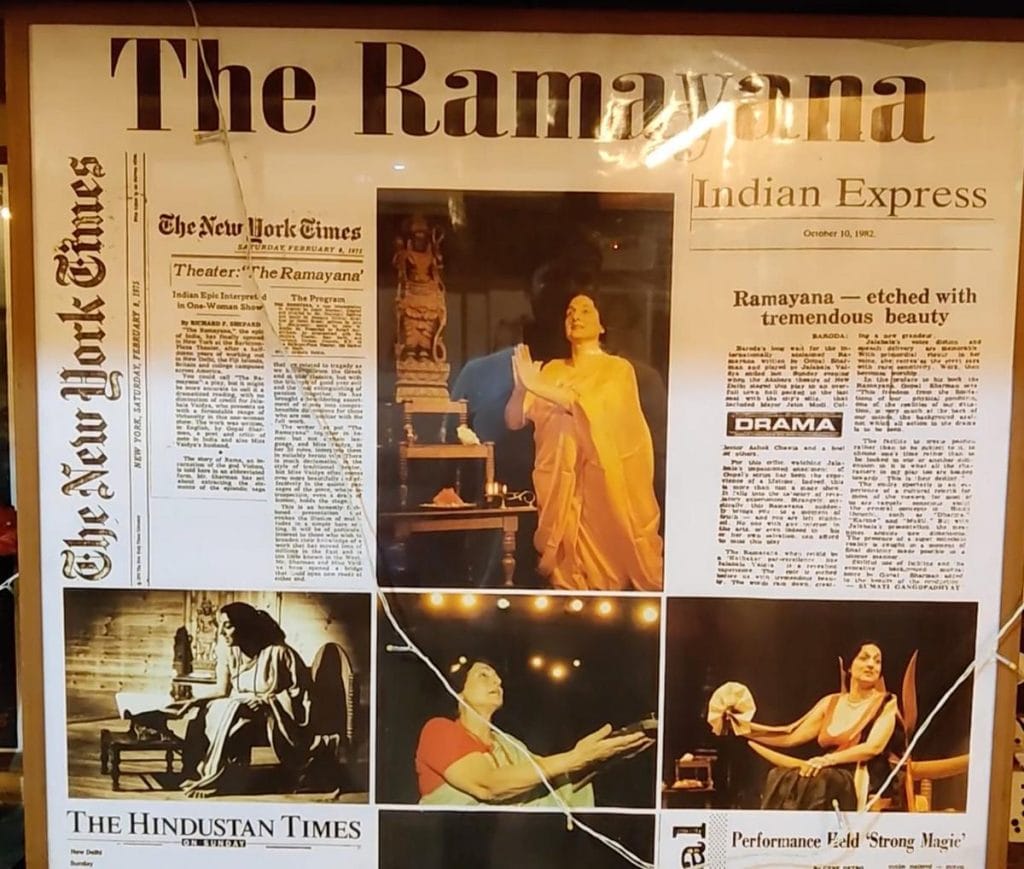

Sharman’s plays—such as Let’s Laugh Again, Full Circle, This and That, Jeevan Geet—and Jalabala’s unforgettable solo of The Ramayana have left their mark on the stage in India and beyond.

But today, Akshara is struggling. Funds are drying up, and censorship is increasing. Its 250-seat amphitheatre and 40-seat poetry space are rarely used anymore.

Vaidya and her family are fighting to keep the theatre alive, even as government help to save both the iconic building and its cultural heritage remains elusive. Online petitions have drawn supporters but not much in the way of tangible assistance.

In many ways, Akshara Theatre is a microcosm of the larger existential crisis sweeping Delhi theatre scene.

“Akshara Theatre has issues that parallel the problems faced by Indian theatre as a whole,” said Vaidya.

The two biggest challenges for any artist, universally, are government interference and funding, according to Akshara Theatre director Vaidya.

Also Read: ‘Political vendetta’? Bengal theatre groups say central funds guided by ‘pick-and-choose’ policy

Carving out a dream—by hand

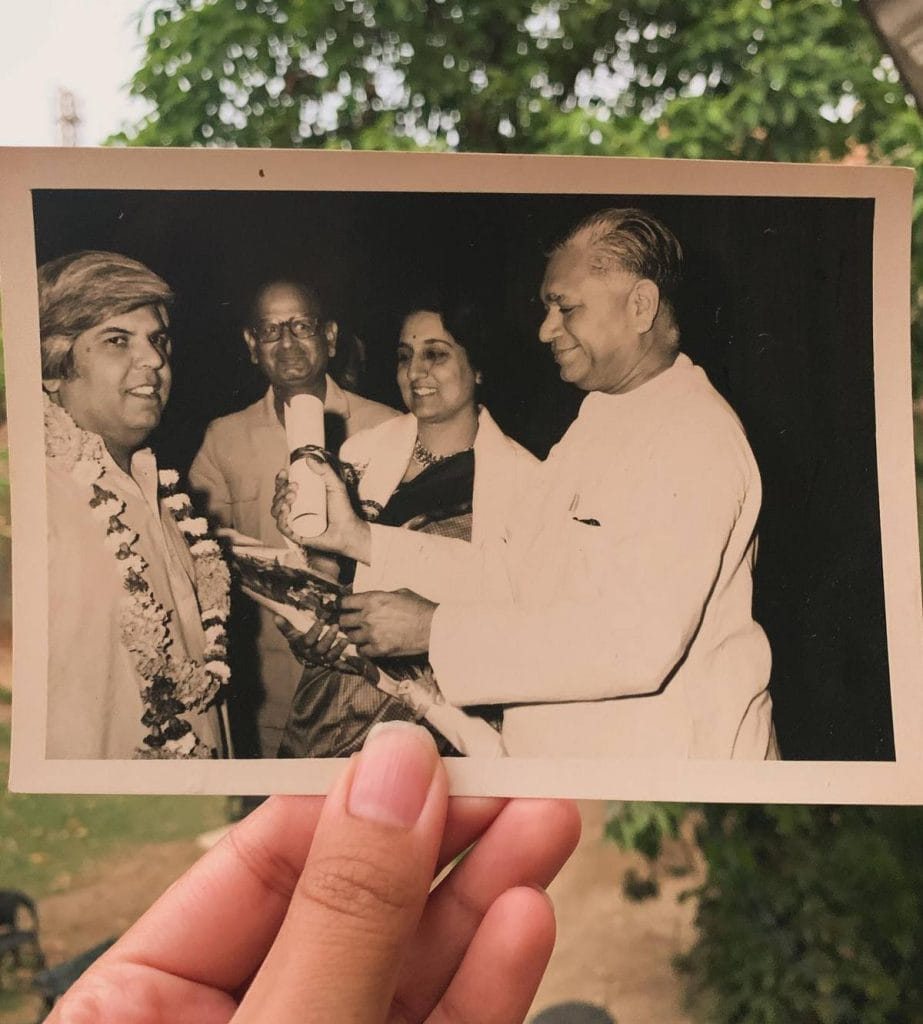

In 1970, at the height of their fame as Indian theatre’s power couple, Gopal Sharman and Jalabala Vaidya met Morarji Desai, then deputy to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to ask for a space for their dream theatre. Desai, in charge of land allocation for such projects, agreed, and the stage was set.

It was an exciting time for the family, recalled Anasuya Vaidya. She was only 11, but already part of her parents’ world of theatre. By the time she was 14, she was performing alongside them, travelling across India on their Bharat Yatra to popularise theatre and provide a platform for young talent. When they decided to build the theatre, her parents made sure she was involved from the start—even taking her to scout for locations.

The search led them through many buildings in Delhi, but none felt right—until they found a vacant colonial bungalow in Connaught Place. It was surrounded by lush, old trees and had tall pillars, wide verandahs, and a spacious, airy layout. Sitting under a blooming gulmohar tree, the family knew instantly: this was it.

But it wasn’t easy getting the curtains to rise. Several architects turned down Sharman, baulking at the complex design. Funds were another problem, despite contributions from the government and companies such as Tata. In the early 1970s, Sharman spent around Rs 3 lakh from his Homi Bhabha Fellowship and tour earnings just to get the theatre started. Later improvements between 1983 and 2003 also soaked up tens of lakhs through grants, fundraisers, and even Sharman’s earnings from TV documentary series.

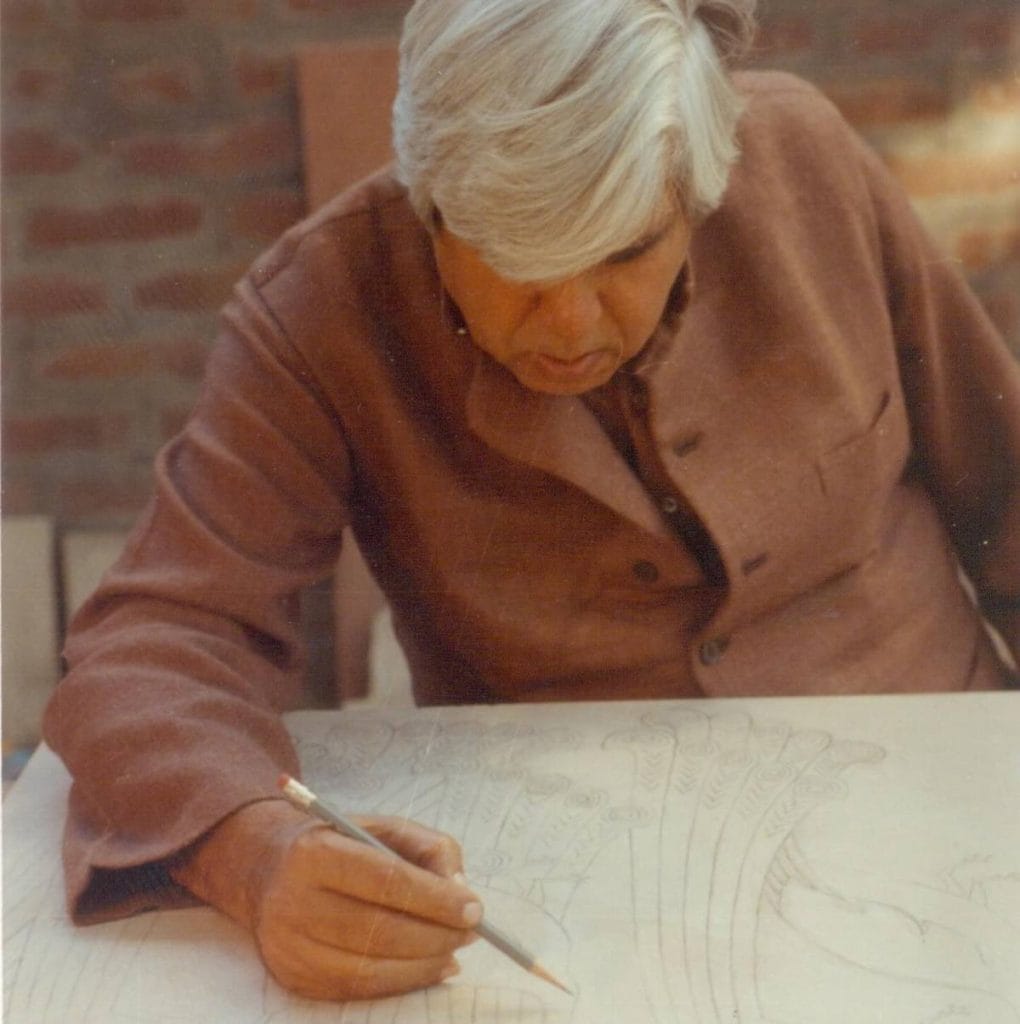

The real cost, though, was in time and effort. Five months into the project, Sharman decided to build it himself. With a small team of three carpenters, two masons, and two labourers, they got to work. One constraint was that the original bungalow structure had to remain intact, so they hollowed it out and built within, adding a lighting room, dressing rooms, an office, multipurpose hall, basement theatre, and studio. Almost everything was made of rosewood, teak, or pine.

“He designed the theatre to resemble a veena, the Indian musical instrument,” Vaidya said, running her hand along the polished chairs. “He used two kinds of wood: hardwoods to project sound and softwoods to absorb it.” Even the curve in the chairs’ top rail was designed to enhance acoustics.

The building itself is a mix of European, Greek, and Roman architectural styles, with a pinkish facade adorned with peacock and mandala carvings, all made by Sharman’s own hand.

“He and his team mastered these intricate techniques themselves,” said Vaidya, her admiration evident.

The theatre’s caretaker, who has worked here for over three decades, added that the building used more screws than nails.

“Gopal Sahib did this so that in an emergency, screws could be removed quickly for an easy evacuation,” he said, asking not to be named.

He also recalled being mesmerised by Sharman’s process, from drawing the design to carving it in stone.

“I saw Gopal Sahab breaking stones with his own hands. Every corner of the building has been made so carefully. The rosewood used here is not just beautiful—it’s strong and durable,” he said.

Akshara lacks the flash and scale of its Mandi House counterparts, but it has something special—its handcrafted, old-world charm. And it’s a lifeline for artists and theatre groups looking for an affordable venue on a tight budget.

Mandi House vs Akshara

Mandi House, Delhi’s theatre district, is a show-stealer. It’s where legends like Naseeruddin Shah, Nawazuddin Siddiqui, and Piyush Mishra cut their teeth. And with iconic venues like Kamani Auditorium, Shri Ram Centre, the National School of Drama, and LTG, it’s a magnet for every intellectual, actor, and ‘creative type’ in town. It’s like an art republic right in the heart of Lutyens’ Delhi, the city’s power corridor.

Here, entire days are spent over cups of chai, discussing art, politics, and revolution. The area has its own ecosystem—like ‘SRC aunty’ Sanjana Tiwari and her poetry volumes, BM Snack Corner dishing out bread pakoras, Bengali Market nearby, a renovated park, and tea stalls aplenty for endless adda.

In contrast, Akshara Theatre sits quietly near Ram Manohar Lohia (RML) Hospital. It doesn’t have Mandi House’s buzzing energy or the facelifts and frills of its venerable old cohorts Kamani and SRC. Open-air performances in its amphitheatre are limited in order to avoid disturbing RML patients. The chaiwala outside is more likely to be serving anxious relatives than actors discussing their next big role.

But Akshara has something special—its handcrafted, old-world charm. And it’s a lifeline for artists and theatre groups looking for an affordable venue.

One such group is Atelier Theatre, which owes its survival to Akshara, according to its founder Kuljeet Singh. He’s been staging his plays here for a decade.

While Kamani charges Rs 1 lakh per show and SRCPA around Rs 50,000, Akshara’s rate is Rs 20,000, or less with discounts. Kamani and SRCPA also have long waiting lists, with bookings required six months in advance and full payment upfront.

“At Akshara Theatre, it is much easier to book a venue just one week before the performance, and payment has never been an issue due to the friendly nature of the staff,” Singh said. “For small theatre groups, Akshara is a crucial space for their existence and survival. We need at least 10 theatres like Akshara.”

In terms of facilities, Singh notes that Kamani’s 632 seats are ideal for large productions, while SRCPA offers only basic amenities despite its steep fees. With such rates, breaking even is difficult.

Artists choose Akshara because of its rich legacy, historic significance, and the deep connections they share with the staff. It has a vintage vibe

-Tushar Chamola, founder of Believer Arts

“Theatre groups can’t benefit from performing in large venues like Kamani,” he said. “It’s easier to manage costs and gain benefits at Akshara.”

Tushar Chamola, founder of Believer Arts, agrees. For him, Akshara holds both “emotional value” and practical perks like “scheduling flexibility”. And with the reasonable rent, it’s easier for theatre companies to keep ticket prices affordable. Tickets at the venue usually range from Rs 100-500.

On 18 August, Believer Arts performed The Great Drama Company, a satirical play about the theatre world, to a full house at Akshara. Tickets were priced at Rs 299.

But there are some drawbacks too.

‘Vintage vibes’, modern woes

Certain types of productions are better suited to Akshara’s intimate set-up.

Recently, a short, small-budget play titled Talat Mahmood, Superstar Singer, Reluctant Actor was staged here with a cosy audience and minimal props. The ticket price was Rs 350. Some in the audience said the smallness of the hall ensured that the play, the actors, and the stage felt up close and personal. But a theatre director noted that Akshara is ideal for baithaks, storytelling, and musical performances, rather than large, elaborate productions.

While Anasuya Vaidya is proud that the theatre doesn’t need major repairs—the durable wood only needs regular cleaning and anti-termite treatments—the quaint charm of Akshara has become something of a disadvantage of late.

Amar Shah, theatre critic and director of Bela Theatre Karwaan, used to rent Akshara’s stage but stopped in recent years. He finds the venue too small for larger productions, and the original lights, designed by Sharman himself, limit more modern experimentation.

“For the audience, this space is uncomfortable. Directors don’t get the proper space. They don’t get freedom to explore their art. They have limitations,” said Shah, who initially staged Mohan Rakesh’s Aadhe Adhure at Akshara but later moved it to LTG Auditorium.

Location is another issue. Akshara’s distance from the nearest metro station makes it less convenient for visitors, and attracting an audience is tough for lesser-known theatre groups.

Competition is also growing in the budget theatre space. Singh points out that Studio Safdar Trust runs a very affordable theatre on the outskirts of Central Delhi, charging only around Rs 5,000 per show, with better lighting than Akshara.

Still, the intangibles keep some artists coming back.

“Artists choose Akshara because of its rich legacy, historic significance, and the deep connections they share with the staff,” Chamola said. “It has a vintage vibe.”

In 1976, while Sharman and Jalabala were performing on Broadway, the family received alarming news—bulldozers had arrived at Akshara Theatre without any warning. Sanjay Gandhi had allegedly ordered its demolition

Bengali Market to Broadway

For Anasuya Vaidya, running Akshara Theatre is about more than just maintaining a venue—it’s about preserving the legacy of her parents and their celebrated plays.

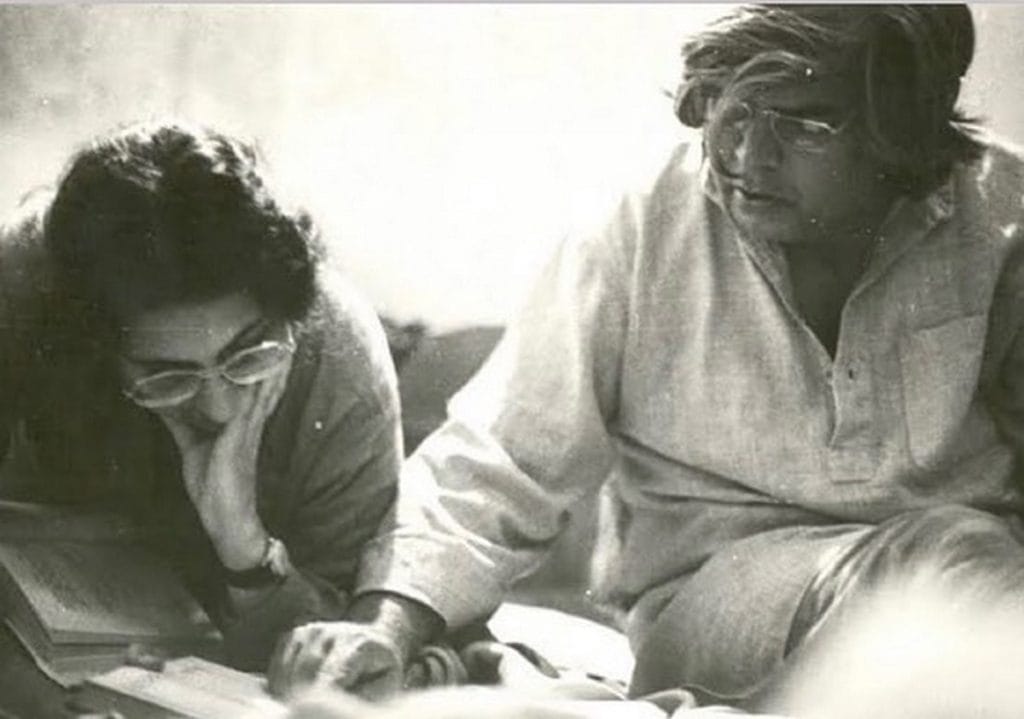

Vaidya said her mother, Jalabala, was working as a sub-editor at Link Magazine when she met Gopal Sharman, a freelance journalist. He was typing up his overdue art column. They snapped at each other—and it was love at first sight.

Jalabala, who died last year, wrote about that moment: “I have no idea how, why and what it was, but that’s how we met and were together since. We began to live together in a garage in Bengali Market. Later, we got married.”

For several years, Sharman wrote a popular column under the pseudonym ‘Nachiketa’, where he explored themes from the Upanishads, life, death, and philosophy. One of his dedicated readers was then President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. When Radhakrishnan underwent cataract surgery in 1966 and couldn’t read the columns himself, he requested that Sharman visit him to read aloud. Nervous about his own skills, Sharman asked Jalabala—who’d had experience acting in college— to read to the President instead.

I personally think power corrupts…Whoever comes to power, one will always be against them

-Gopal Sharman in a 2014 interview

This moment became a turning point for the couple. After a week of rehearsals, they visited the President’s residence. Vaidya recounted how her father and brother waited outside while her mother spent 45 minutes reading to a room of intellectuals and scholars. Radhakrishnan was so impressed that he suggested Jalabala perform for the public, even instructing his assistant to organise a programme.

That first public performance, Full Circle—a dramatic reading of Sharman’s stories—took place at Azad Bhavan and was a hit. Soon after, the Italian and Yugoslavian ambassadors invited the couple to perform in their countries.

“Everything was happening smoothly and naturally,” said Vaidya.

The European tour was a resounding success. Full Circle wowed audiences. At Italy’s Teatro Goldoni, the world’s oldest operational theatre, Jalabala’s performance earned standing ovations, and their shows sold out. Even the Pope attended one of their performances. The couple also toured London, staging Full Circle at the Arts Laboratory and Mercury Theatre.

The two years they spent in London became a period of intense creative collaboration. Vaidya said her father would lie on the floor in a dark room late at night, lost in thought, narrating his ideas aloud. Jalabala would write them down, turning his musings into early drafts.

And then, Broadway called.

‘The Ramayana’ in NYC

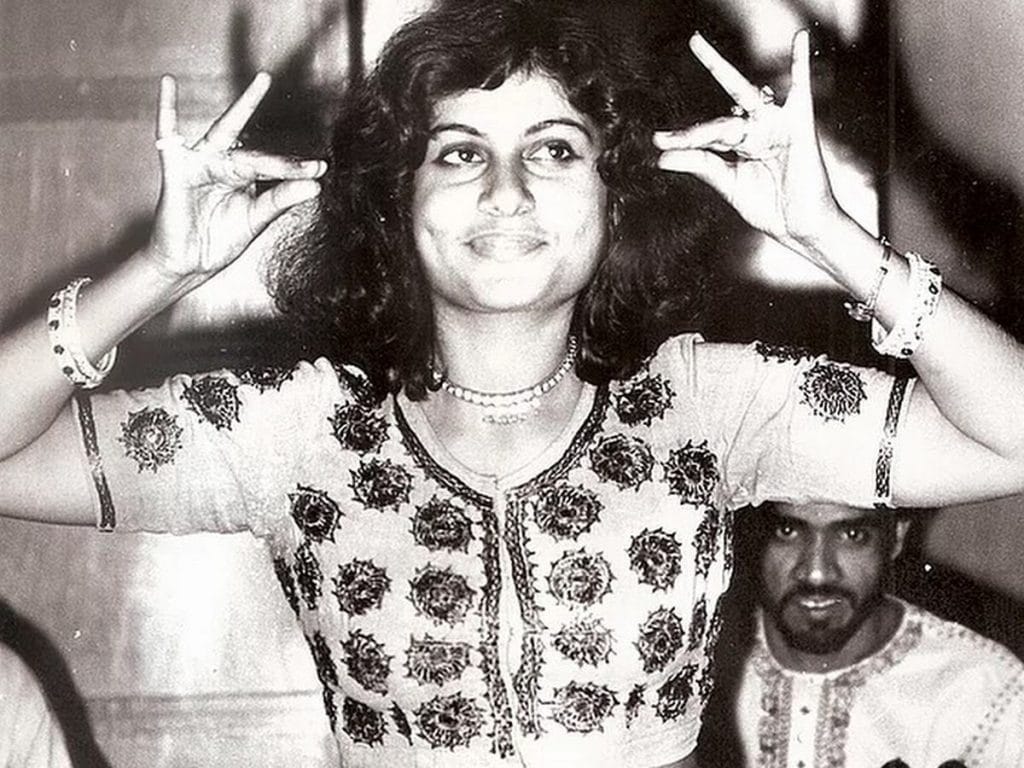

In Akshara Theatre’s waiting room, large framed photos of Vaidya’s childhood and important theatre productions decorate the walls. One play stands out—The Ramayana, a defining production for both Gopal Sharman and Jalabala.

While still in London, Sharman began reinterpreting the epic. Rather than portraying Rama and Sita as gods, he humanised them. But the play’s true USP was something else—it was a one-woman show, with Jalabala playing all 22 characters.

Created for the Royal Shakespeare Society’s World Theatre Season, one of the most prestigious stages in the 1960s, the play eventually made its way to New York’s Broadway in 1975. Jalabala became the first Indian woman to perform there, earning rave reviews.

“Jalabala Vaidya… presents us with a formidable range of virtuosity in this one‐woman show,” said a New York Times review. “The writer has put The Ramayana together in heroic but not archaic language, and Miss Vaidya, in her 20 roles, interprets them in suitably heroic vein.”

Back in India, meanwhile, Akshara Theatre was pushing boundaries with its hard-hitting political plays.

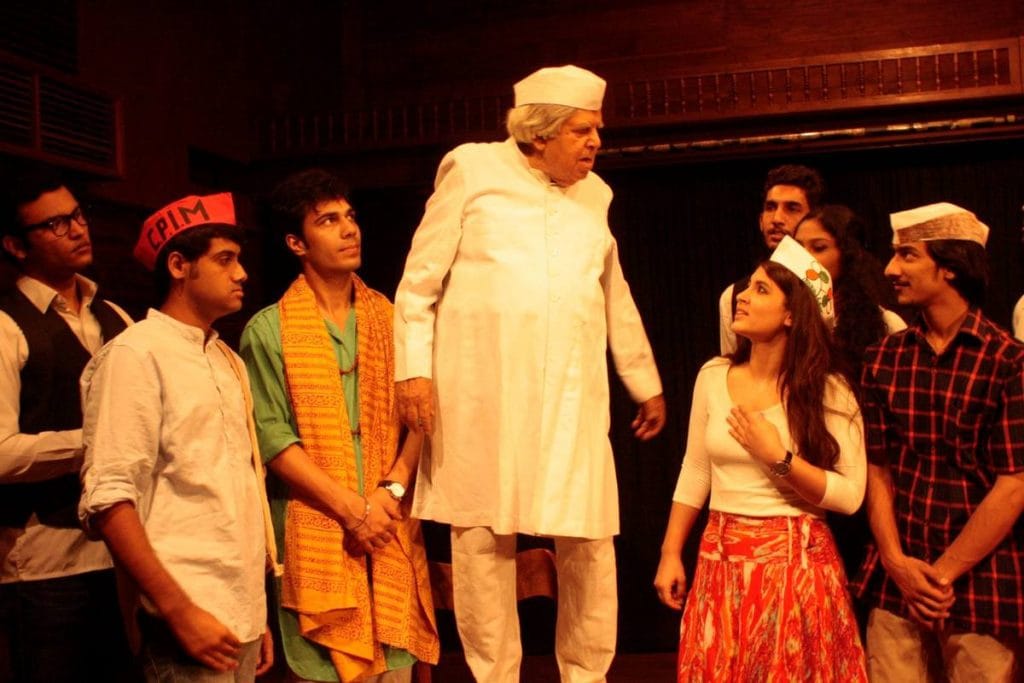

Akshara’s tradition of defiance continues to this day. The popular political stand-up comedy Aisi Taisi Democracy premiered here in 2014, two months after Narendra Modi came to power.

Brush with bulldozers

During the Emergency, Akshara Theatre staged Let’s Laugh Again, a biting political satire by Gopal Sharman that ran to packed houses for six months, right up until 1977 when the Emergency ended. But the play caused more than just a stir—it nearly cost them their theatre.

In 1976, while Sharman and Jalabala were performing on Broadway, the family received alarming news—bulldozers had arrived at Akshara Theatre without any warning. Sanjay Gandhi had allegedly ordered its demolition in retaliation for the play’s political undertones.

Vaidya speculated that one particular scene in Let’s Laugh Again might have provoked him

“We had a character who played with toy cars and cried for mummy when they broke,” she said.

When they heard about the bulldozers, Sharman and Jalabala contacted Indira Gandhi from New York. She heard them out and invited them to tea upon their return.

When the meeting finally happened, Vaidya said, Gandhi asked the couple if they thought she was a dictator. Gopal suggested airing a satire on Doordarshan to show Gandhi’s support for free media, with no censorship. Indira agreed but wanted to see the show first. When the couple refused, she gave her approval anyway.

However, while filming the proposed satire, a letter arrived from the Prime Minister’s office, demanding to preview five minutes of the show, with promises that no changes would be made. But one official objected, saying the show might “demoralise” the bureaucracy. To this, Indira’s daughter-in-law Maneka Gandhi joked that the show might be what the country needed. This show was never broadcast.

As for Let’s Laugh Again, it continues to be staged, with updates and topical jokes each time. What’s stayed consistent is its anti-establishment tone, no matter the government in power.

Other well-regarded political satires performed at Akshara include Sharman’s India Alive, La La Land, Karma, and Larflarflarf. That tradition of defiance continues to this day. The popular political stand-up comedy Aisi Taisi Democracy premiered here in 2014, two months after Narendra Modi came to power.

“I personally think power corrupts…absolutely. Whoever comes to power, one will always be against them,” Sharman said in a 2014 interview, two years before his death.

Limitations and censorship

The two biggest challenges for any artist, universally, are government interference and funding, according to Vaidya.

“Independent artists who aren’t affiliated with any political party tend to face problems. And theatre is a medium for freedom of expression, it is fundamental,” she said. “If we want to express something, we should be able to do it.”

Vaidya added that the issues of funding and government are deeply intertwined in the arts because the government is often the primary benefactor. Most artists have limited resources, and private-sector patronage is rare.

Akshara Theatre needs either reform or revival, as it has now become just a commercial space

-Delhi-based theatre director

“In India, the corporate funding for art is pathetic. And the corporate companies don’t feel any responsibility towards arts and artists,” she added.

Despite these hurdles, Akshara Theatre has built a repertoire of innovative productions, from The Ramayana to Karma, a Sharman classic that manages to blend the god of death Yama, aliens, and a dystopian society into a comedy with song and dance.

“There was a fusion of modern and classical. We did a lot of original work here in the tiny theatre,” said Vaidya.

In recent years, she too has written several original plays for children— Train to Darjeeling, All Alone at Home, The Jungle Adventure, and All You Need Is Love— hoping to connect the new generation with Akshara’s rich legacy. Vaidya is currently working on recreating her father’s Ramayana, this time featuring multiple actors, since she’s convinced no one can replicate Jalabala’s virtuosity.

For others, however, the theatre itself is past the point of return. A 52-year-old theatre artist, asking to remain anonymous, said no major new plays or talents have come from it in years.

“Akshara Theatre needs either reform or revival, as it has now become just a commercial space,” he said.

Going dark—nearly

In 2016, an unpaid electricity bill of Rs 3 lakh nearly pushed Akshara Theatre to the brink of closure. This set off a campaign by artists to raise funds through crowdfunding and donations. While many contributed, comedian Papa CJ reportedly paid the full amount as a gesture of his affection. The extra funds collected were used to cover future expenses and bills.

Previously, the hall was rented to other theatre groups for Rs 6,000 per show, according to theatre director Amar Shah, who himself staged numerous plays there. However, after the electricity bill crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, Akshara increased its rental charges. Shah stopped booking the venue, deciding that the amenities no longer justified the price.

“That’s also their compulsion,” he said. “They have few people to help them and they can only earn through their plays,” said Shah.

Vaidya, however, insisted they still offer the space for free to many artists. Tushar Chamola confirmed he has used it for free rehearsals.

Also Read: Shabana Azmi to Naseeruddin Shah, how Bollywood stars breathed life into Delhi’s theatre scene

New gen, gurukul & gharana

A new, third generation is emerging at Akshara Theatre. Anasuya Vaidya’s adult children—Nisa, Dhruv, and Yashna Shetty—are preparing to eventually take the reins.

On the wooden stage, performers, including the siblings, are rehearsing The Patient, a suspense thriller directed by Vaidya. The scene features a doctor and a police officer questioning five murder suspects. Vaidya watches like a hawk, quietly guiding the actors whenever there’s a misstep.

Nisa, Dhruv, and Yashna have all grown up learning about theatre, singing, and dance from their maternal grandparents. Nisa has made a name for herself as a singer, even performing with AR Rahman. Dhruv and Yashna, aside from acting, are also involved in the theatre’s management.

Dhruv wants to make sure the theatre retains its identity as a platform for “all types of performances”. He rejects claims that the theatre has lost its edge.

“I don’t think there have been a lot of changes. Conventional theatre is still the same and the plays that are coming are still the same,” he said, adding that Akshara still stages everything from comedies to political satires.

Nisa echoed this, saying that the theatre hasn’t lost its essence.

While some critics, like Shah and the 52-year-old director, have raised concerns about nepotism within the family, Vaidya cites the Indian performing arts traditions of gharanas and gurukuls. She wants official recognition and support for these models, based on the familial lineage of gurus or ustads.

Despite years of advocacy, Vaidya said, the government has yet to recognise most of these institutions as key training centres.

“You have Kalakshetra. But, how many students do they produce in a year—20-30?” she asked.

Although Vaidya said the lack of recognition doesn’t affect Akshara’s daily functioning, an existential threat is always looming.

“It takes all of an artist’s talent and intelligence to just survive,” she said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)