New Delhi: A gigantic brown cloud named Bhura threatens to devastate Mumbai until four preteens band together to stop it. In a future without rain, 10-year-old Anoushqa decides she will make it pour again. Meanwhile, in Kerala, young Ammini watches the 2018 floods drown her world and sets out to find out why.

These are the plotlines of some of the most famous children’s books in India in the last five years—A Cloud Called Bhura, The Little Rainmaker, and Ammini Against the Storm. It’s a new age of Indian environmental fiction for children. Writers are building on a rich history of nature writing by the likes of Ruskin Bond, Zai Whitaker, and Ranjit Lal. But rather than just observing the environment, these stories reckon with the crisis confronting it.

“Ruskin Bond and Zai Whitaker wrote about the natural environment for children. But now, the writing is no longer just observant and descriptive,” said Sudeshna Shome Ghosh, the publisher of the children’s section of Speaking Tiger. “Now, we write about the environment as we see it, through our everyday interactions. The way we view the environment itself has changed, and so has our writing.”

With climate activist Greta Thunberg’s 2018 call for Fridays for Future—a movement to skip Friday classes for climate protests—climate change began gaining ground as a theme in children’s literature. Through picture books, non-fiction histories, and cli-fi (climate fiction) novels, Indian authors are tackling topics such as wildlife conservation, global warming, and the climate crisis in innovative ways for children.

Children’s books are probably the near-perfect medium (to explore climate change). If they understand climate change and how important it is to think about its effects at an early age, it sticks and they become more aware. The new-age books and how they tackle climate change are mind-boggling.

-Venkatesh M, director of Eureka Books

Publishers are taking notice, universities are offering short courses on the subject, and there’s even a Green Literature Festival. Most importantly, children love it.

“Without an emotional connection to nature, how can future climate leaders make the right decisions when it comes to it? These decisions emanate from emotion, not logic,” said Harini Nagendra, an author and director of Azim Premji University’s Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability, which offers a course on nature writing for children. “Books are the best way to develop this connection.”

Also Read: Climate fiction is growing, but it’s waiting for a Chetan Bhagat

Cli-fi is the new sci-fi

Former journalist Bijal Vachharajani learned about the Asian brown cloud—a vast pollution-driven haze—while studying for her master’s in Costa Rica in 2011. That’s when the idea for A Cloud Called Bhura, possibly India’s first climate fiction book for children, began to take shape.

“I was thinking about how so much of our knowledge about climate change comes from the people around us or media and TV, and not from actual science,” said 45-year-old Vachharajani, adding that her master’s degree in Environment Security and Peace gave her the tools to examine climate with the precision required. “I wanted to write something rooted in facts, yet entertaining too.”

Like the ominous cloud in her book, Vachharajani’s idea grew over the years. At the time, climate fiction for children was still a relatively new concept in India, and she wanted to blend satire with serious climate science. As a resident of Mumbai, she set the story in the city, drawing from her own experiences of the 2005 floods to describe some of the scenes.

In 2019, Speaking Tiger picked up A Cloud Called Bhura and it soon became a global bestseller, winning awards and continuing to be read aloud at children’s festivals even today.

“When she initially wrote it, there’s a scene where the AQI in Mumbai goes up to 400 because of the cloud—it felt like an unimaginable, cli-fi number,” recalled publisher Ghosh. “But now, 400 isn’t even surprising for Mumbai, let alone Delhi.”

Be it Aesop’s Fables or Panchatantra, kids’ literature was too moralistic. When it came to the environment, we needed books that actually connected children to the world around them

-Shashwat DC, coordinator of the nature writing for children course at Azim Premji University

It is this blend of reality and fantasy that makes climate fiction so compelling for eco-conscious young readers.

For 7-year-old Anaika Dalmia in Bhubaneswar, books like these introduce her to new worlds while making her think about the one she lives in. When the municipality authorities cut down a tree outside her house in early January, she was anxious.

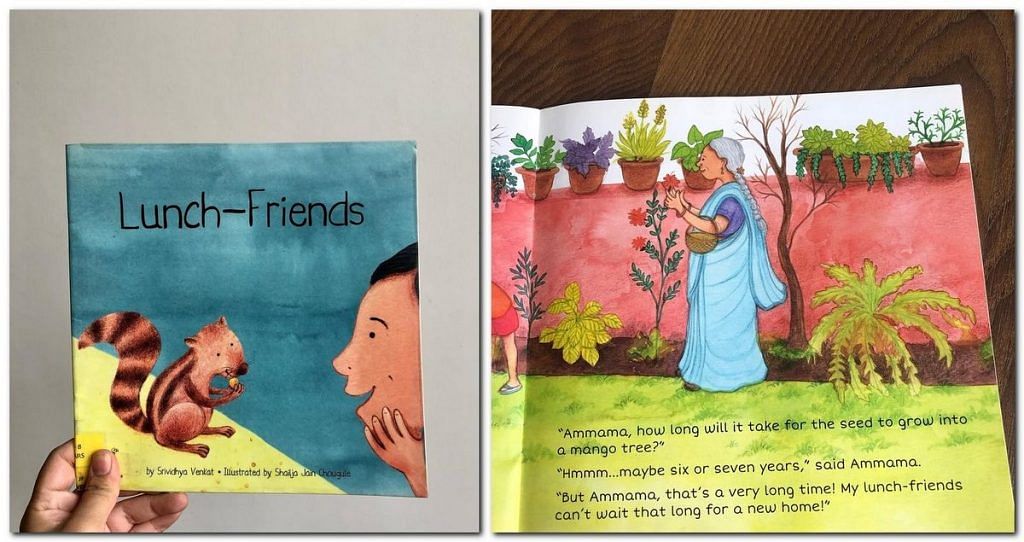

“What about all the squirrels and the birds living in the tree? Should we plant another one for them? What would Mihir do?” she asked, referring to the protagonist of Srividhya Venkat’s Lunch Friends, who faces a similar dilemma.

Dalmia also worries about her aunt in Mumbai—what if Bhura’s destruction reached her? At the zoo, she warns her younger brother not to tease the tigers.

For her, every tiger is “Macchli”— the titular big cat from Supriya Sehgal’s book of real-life animal stories, which her teacher once read to the class.

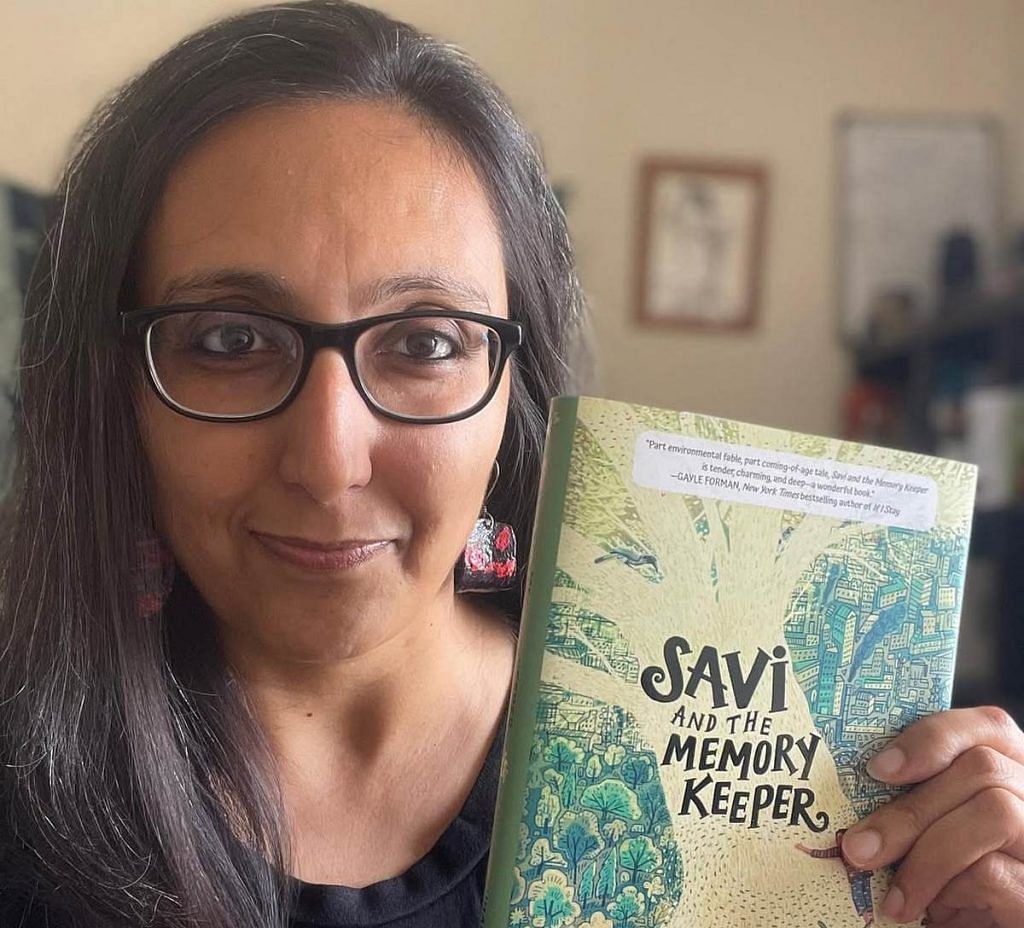

Many of the children Vachharajani meets tell her how her books—including Savi and the Memory Keeper, The Great Indian Nature Trail, and Bhura—help them understand the world, especially as extreme weather events, air pollution, and heatwaves make the headlines regularly.

“I had once visited a few schools in Ahmedabad in 2024, and the students there requested me to read from the chapter where Bhura’s rain causes floods in the city,” recalled Vachharajani. “Ahmedabad had seen flooding that year, and reading about it in fiction helped them make sense of how it happened.”

Picture books, primers, planet—no ‘preaching’

At the HarperCollins stall at the World Book Fair in Delhi, 10-year-old Aliya Mehta cajoled her father, pointing to a book just out of her reach. She wanted Our Potpourri Planet, the latest book by famed children’s writer Ranjit Lal, which hit shelves on 31 January.

“My English teacher told me about it—it’s on climate change, Papa,” she said, emphasising the phrase she had just learned in class.

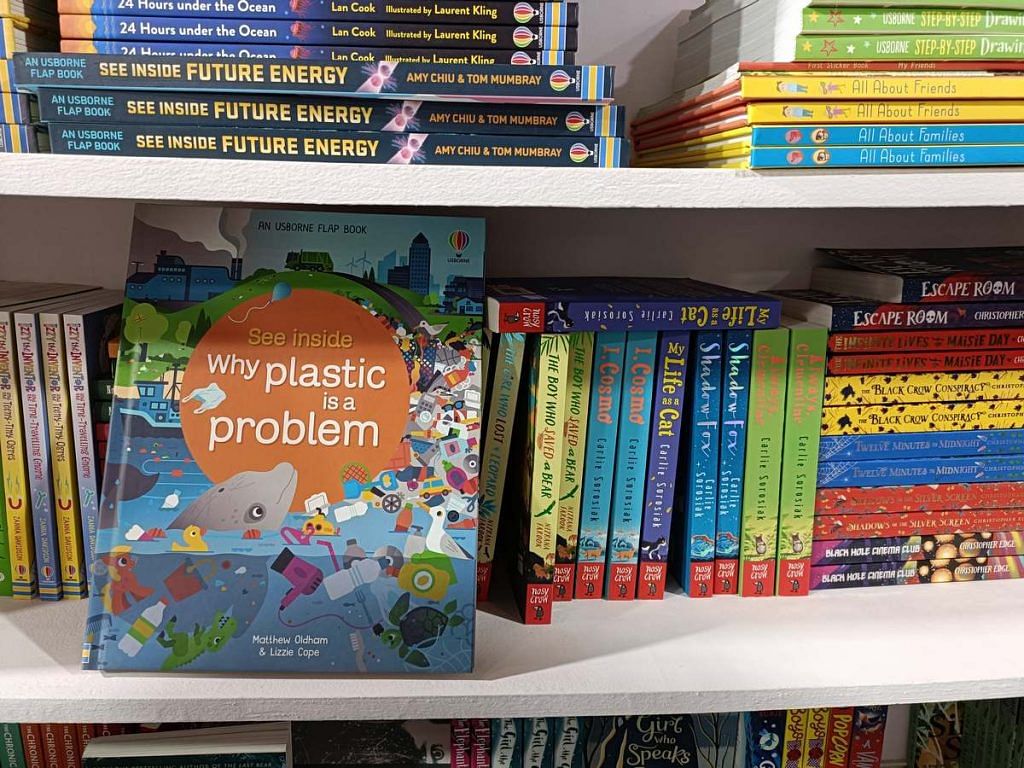

Lal’s book had plenty of competitors in the kids’ climate genre. At every major stall, wedged between Percy Jackson, Diary of a Wimpy Kid, and Harry Potter, were small corners dedicated to nature and the environment. For younger readers, there were picture books on trees, birds, animals, and bees. And older children had their pick of fiction and non-fiction, from mystery novels on wildlife trafficking to primers on plastic pollution.

“They’re learning about it in schools—about how to conserve water, plastic pollution, and global warming,” said visitor Tamanna, whose 8-year-old daughter studies in Delhi’s GD Goenka school. “But reading about it in books makes them understand so much better.”

Parents aren’t the only ones seeking out these books. Since the National Education Policy of 2020 mandated environmental education across classes, demand has also grown from schools.

“It isn’t just the kids that want to read these books. We’ve had five to six school librarians enquiring about the best novels on the environment to stock in their schools,” said a stall manager at the World Book Fair.

This interest extends to non-fiction as well.

Around the time that Vachharajani came out with Bhura, author Meghaa Gupta was working on what would become another children’s bestseller—Unearthed: The Environmental History of Independent India, published by Penguin.

Released in 2020, Unearthed is a comprehensive primer on India’s environmental landmarks, from the Chipko movement to the National Action Plan on Climate Change. But it’s not textbookish and dry. It’s filled with illustrations and trivia to keep kids engaged. Four years later, people still flock to buy it.

“Unearthed was one of the first books of my daughter’s that even I enjoyed reading—I learnt so much from it,” said Aliya’s father Tarun Mehta, a software engineer. “I mean, we know about the Narmada Bachao Andolan, but who knew about the Silent Valley protests? The side effects of the Green Revolution? I think it’s a must-read for every child.”

With kids, you always have to experiment with format and content. The second you become too preachy, they automatically lose interest.

-Bijal Vachharajani, author

Another popular non-fiction title in this genre is Nita Ganguly’s 365 Ways to Save the Environment, a 2021 book that lays out small and large actions children can take to protect the natural world. Both Gupta and Ganguly have backgchildrenrounds in environmental science and biology and approach conservation with depth and nuance, offering a perspective children seldom see.

And it’s not only preteens and young adults. Younger readers are engaging with environmental themes in their own way.

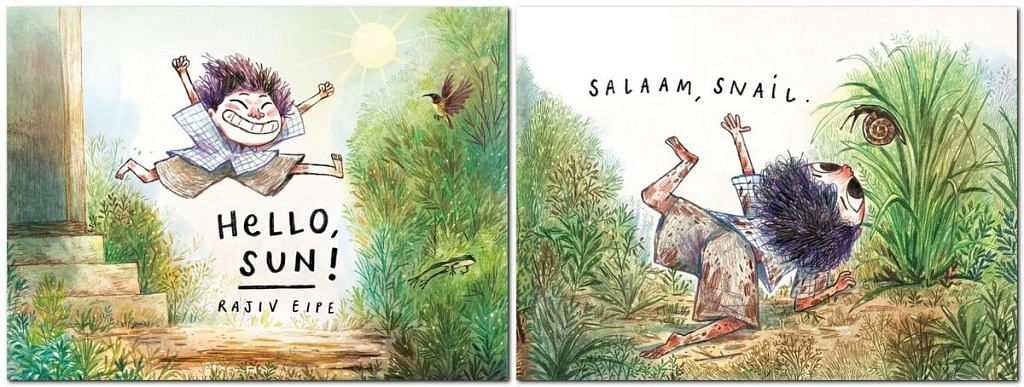

Mehta is also introducing his younger daughter Ada, 4, to eco-oriented books she can relate to. She’s too young to read complex prose, so he’s getting her started with picture books. In this search, he came across illustrator Rajiv Eipe and bought his latest book, Hello Sun, which came out in 2024.

“It is so rich and vivid, and even though she’s barely old enough to read two words together, she’s still learning the names of the insects and birds he mentions in the book—birds I can show her in real life too,” said Mehta.

Hello Sun, published by Pratham Books, is a vividly illustrated story about a young Indian boy discovering the world around him—from snails to spiders to wildflowers. It won the Book of the Year Award (Children’s Category) at the Green Literature Festival 2024.

“With kids, you always have to experiment with format and content,” said Vachharajani, who has collaborated with Eipe on illustrations for her book too. “The second you become too preachy, they automatically lose interest.”

Writing nature for kids

Children’s books on environment and climate change are not about dry recitals of facts and figures. Indian authors are aiming to stir emotions through personal narratives and hopeful portraits of humankind’s connection to nature.

The point isn’t just to spread awareness about the 1.5℃ global warming limit, but to “make children fall in love with the rare and beautiful natural world around us”, said Harini Nagendra.

harini.nagendra

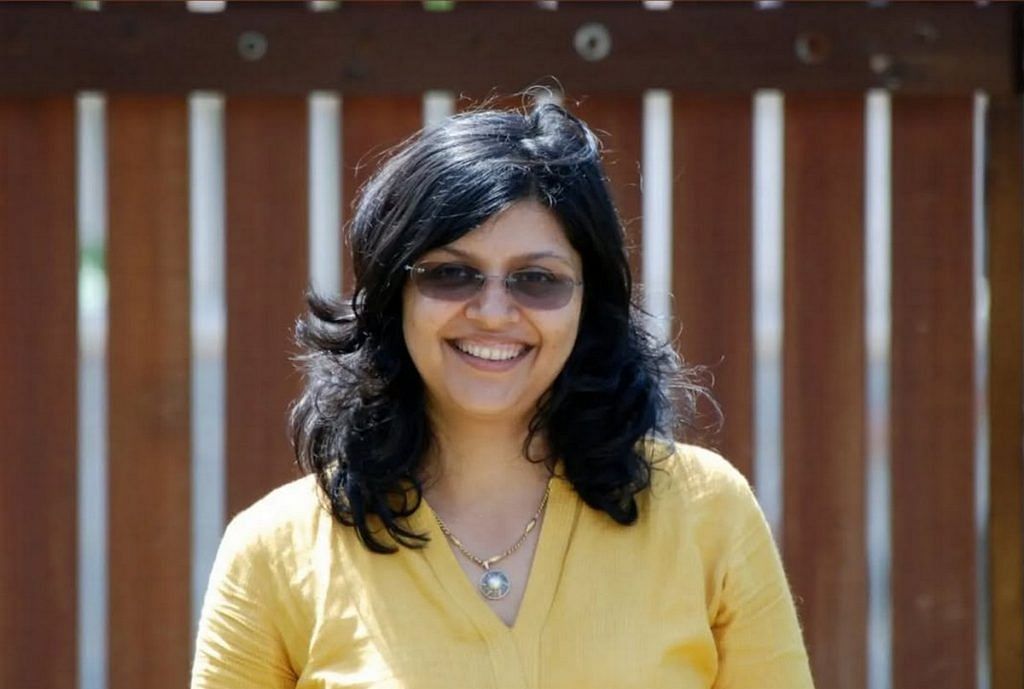

As director of the Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Nagendra helps aspiring writers bring the environment to life in a way that speaks to children’s magical imaginations—where trees can talk and every animal has a story.

“How do you make the environment exciting and inviting for kids? How do you lay out the environmental crisis without it sounding daunting? How can you instil hope in stories about climate and global warming?” These were some of the questions she asked herself about children’s literature in India.

In 2020, she and her colleague Shashwat DC launched a series of webinars bringing together publishers, illustrators, and authors in the field of environmental children’s literature. Their goal was to spark conversations, build networks, and foster an ecosystem of climate storytelling that went beyond moral lessons.

The following year, the webinars led to the university’s first nature writing for children course, which spanned a weekend and drew students from across the country.

“Be it Aesop’s Fables or Panchatantra, kids’ literature was too moralistic. When it came to the environment, we needed books that actually connected children to the world around them,” said Shashwat, coordinator of the course.

Now in its sixth edition, the course has brought together over 100 students in batches of 20-25 to explore how to write about environmental issues for children. One of the sessions even took place in Pench National Park in Madhya Pradesh, providing authors with an immediate catalyst for nature-focused storytelling.

“Our goal is simple—we want the right authors to meet the right publishers and illustrators,” said Shashwat. “The Indian landscape and ecosystem is unique, and it needs a unique approach from both policymakers and artists.”

Kindle your flair for nature writing! Join Azim Premji University’s Nature Writing for Children online course. Use our expert guidance to refine your stories based on flora and fauna. Submissions open till 5 October. Register now: https://t.co/4GhTQuUmep pic.twitter.com/CSSSpU0CeB

— Azim Premji University (@azimpremjiuniv) September 30, 2024

Over the past four years, the course has featured authors like Bijal Vachharajani, Bahar Datt, Zai Whitaker, and Rajiv Eipe, along with publishers from HarperCollins, Karadi Tales, Speaking Tiger, and Penguin. They guide aspiring writers on how to pitch stories, choose the right format, and craft strong narratives.

For Nagendra, the course is more personal. She calls herself an ‘accidental ecologist’—someone who stumbled into a climate career, but loved nature as a child. She hopes books can do for others what nature did for her.

“So many children nowadays are growing up in urban settings with limited access to the natural world,” said Nagendra. “As future leaders, shouldn’t we want children to have an affinity for nature, especially in the Indian context? This affinity comes from books.”

Also Read: Harry Potter sealed the defeat of Hindi books for children. But a new ‘pitara’ looks promising

Crime, comedy, and climate

Climate storytelling in India is going beyond conventional formats, according to Venkatesh M, the director of Eureka Books and organiser of Bookaroo, India’s biggest children’s literature festival.

“Children’s books are probably the near-perfect medium (to explore climate change). If they understand climate change and how important it is to think about its effects at an early age, it sticks and they become more aware,” he said. “The new-age books and how they tackle climate change are mind-boggling.”

Now, he added, there are stories about climate migration, comics with environmental themes, and tales where children are crusaders for the planet.

Pankaj Sekhsaria, an activist and chronicler of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands’ ecology, turned to fiction to bring real-world environmental stories to young readers.

His 2021 book, Waiting for Turtles, is a delightful story about a boy who goes to observe Olive Ridley turtles with his mother.

“There are millions of such stories in every corner of India, and I felt they deserved to be told authentically. Children’s books are a good medium to tell them,” said Sekhsaria.

Climate fiction isn’t limited to children’s books. Trisha Niyogi, director of Niyogi Publishers, points to authors like Rajat Chaudhuri, who weave environmental themes into fiction for adults. His 2024 novel Spellcasters mixes industrial pollution, agricultural biotechnology, and renewable energy with noir, crime, and thriller tropes.

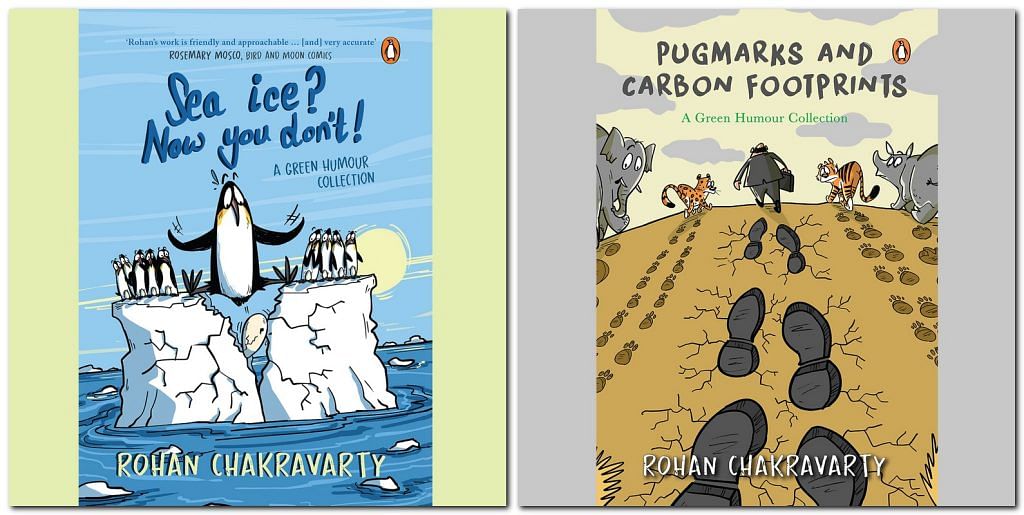

Humour is another nascent sub-genre. Rohan Chakravarty, creator of the acclaimed cartoon column Green Humour, addresses global warming and climate change through satire. His work, published both independently and in anthologies, has won awards at the Green Literature Festival 2021, the Sanctuary Asia Young Naturalist Award, and the Bangalore Literature Festival.

For Vachharajani, leaving climate change out of contemporary fiction would be more surprising than including it.

“If you write a book set in the present day and don’t have any mentions of climate change, that would be the real science fiction,” she said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)