Mumbai: The phone rings every evening between 7:30 and 7:40 pm in the office of the murdered anti-terror Mumbai lawyer Shahid Azmi. It was at this hour that he was fatally shot five times 12 years ago. And his mother, Rehana, has been dialling the number every day since.

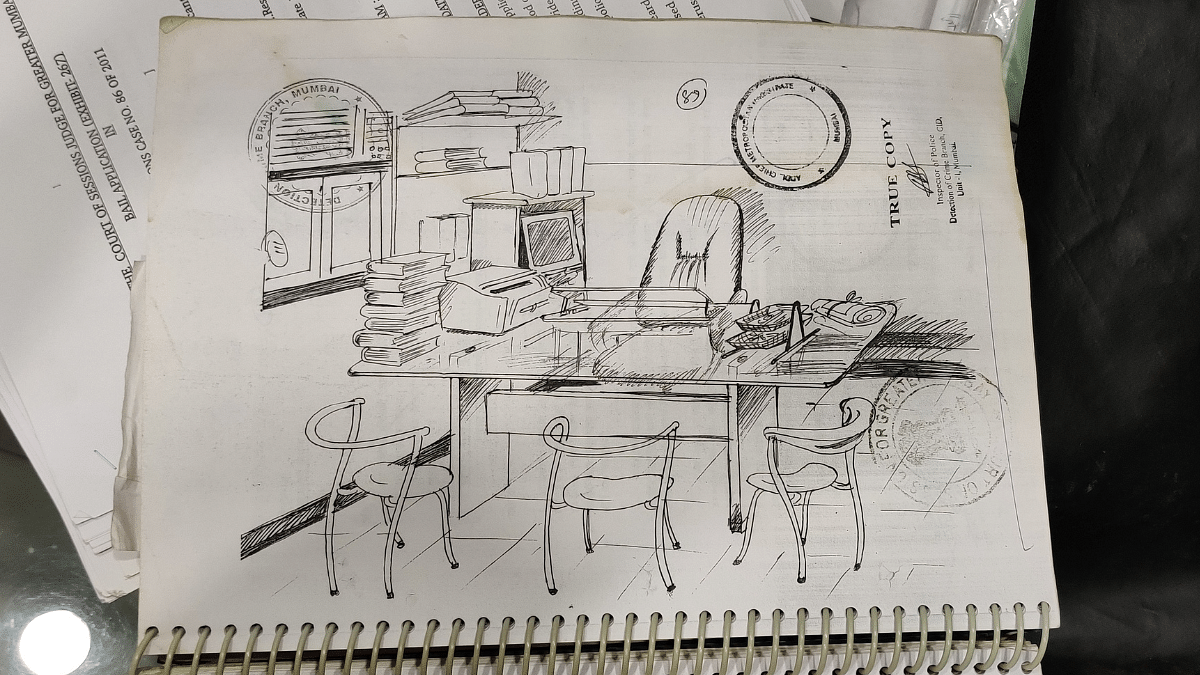

Now, sitting in Shahid’s chair, brother Khalid Azmi picks up the phone. “Yes mummy, I’ll do it right now, I’m still here,” he assures his mother on the phone in a small, two-room office on the ground floor in Taximens Colony, Kurla, Mumbai.

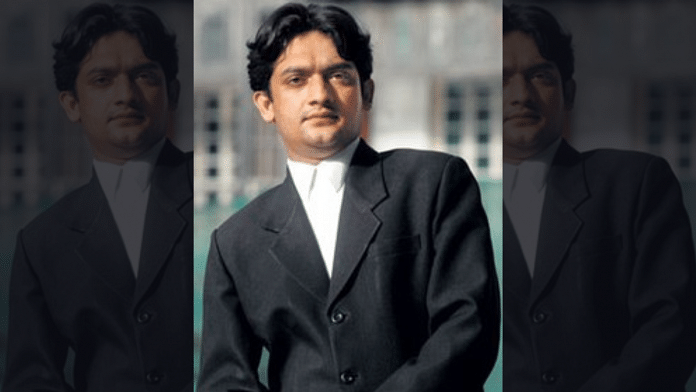

Advocate Shahid Azmi, immortalised in Hansal Mehta’s critically acclaimed movie Shahid (2012), fought relentlessly for the wrongly accused in terror cases. But over a decade on, the feisty lawyer’s murder trial remains stuck in the same judicial bottlenecks that he mastered. The case has since come up for hearing over 370 times, judges handling the case have changed over 15 times, the prosecution and the accused have sought multiple adjournments, only about 12 witnesses out of 109 have been examined, and the trial court has spent time dealing with several applications filed by the accused, including those demanding a wristwatch and a “special bed” in jail.

Meanwhile, Shahid’s family has battled a long wait and ‘betrayal’ from an organisation that had earlier helped him fight the cases he is known for.

Now, Khalid is a lawyer too, but he does not want to be in the ‘limelight’ like his brother and says, “I have seen my brother doing everything. What did he get in return?”

His question hangs in the air alongside the dozens of yellow, pink, and green case files stacked in a steel storage rack to his left. One of these case files, the only one wrapped in black, is Shahid’s.

The betrayal

Those who knew Shahid attest to the fact that his zeal to fight for the wrongly incarcerated came from his own struggles with the legal system. He spent five years in Tihar Jail in the 1990s after being arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act’s older and more stringent predecessor – the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act. Shahid was 17 at that time.

Khalid remembers getting a call from Shahid when he was released. The latter had two asks — a form for LLB admissions and another for journalism.

During his seven-year stint as a lawyer, Shahid worked closely with Jamiat-Ulama-e-Hind, which often helped him with the donations to engage senior advocates in the high courts and the Supreme Court. It was this association through which he took on the State machinery in several high-profile cases, including the 7/11 Mumbai local train blasts, the 2006 Malegaon bombings, the 2006 Aurangabad arms haul case, and the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks case.

Secretary of Jamiat-Ulama-e-Hind’s Maharashtra unit Gulzar Azmi is still all praises for Shahid. He mentions how Shahid was always “forward-looking” and credits his legal strategies for several acquittals, including the 2016 acquittal of nine Muslim men in the 2006 Malegaon blasts. He explained that it was Shahid’s idea to go to the Supreme Court to challenge the constitutional validity of a MCOCA provision in 2007. The immediate effect of this petition was that the SC stayed the trials in the Malegaon blasts case from February 2008 till April 2010 when the judgment was pronounced. Azmi said that while the challenge was unsuccessful, the stay bought them time. In January 2011, Swami Aseemanand confessed to the Malegaon blasts in CBI custody, finally leading to the discharge of the accused in April 2016. Gulzar also says about how Shahid himself never asked for any money for fighting these cases.

“There is no doubt that Shahid Azmi was handling trials only out of sympathy. We used to give him (money) sometimes, but he never asked for it. He was sympathetic because he had gone through that phase,” he says.

Shahid’s fight was, however, cut short on 11 February 2010 when he was murdered in his office by three men posing as his clients. Khalid seemed to be the natural heir to his legacy.

And Khalid did try. He worked with Jamiat on a few cases that were pending with Shahid. However, this association ended around 2015 due to what Khalid now refers to as a “betrayal”. He says that after his brother’s murder, Jamiat assured him that they would appoint a senior advocate to take care of the trial. He claims that whenever he asked Jamiat about Shahid’s case, he was given assurances and promises. “They always told me, you don’t worry about the case, we are taking care of it. So, I just focused on my work.” However, in 2014, he realised that it was only the public prosecutor and that Jamiat had not appointed any lawyer from its side.

“This made me and my family a little angry and emotional. It left us very disturbed because we gave our everything to this organisation, and now, it is backing out,” he says. Khalid then distanced himself from Jamiat.

In response, Gulzar Azmi maintains that Jamiat did not have that power and that it was the family’s prerogative to appoint a lawyer.

“Since this was a police case, we could not have interfered in it a lot. So to say that Jamiat-Ulama-i-Hindi did not show interest in the case, according to me, is a misrepresentation,” he says.

Khalid, however, still has questions. “If my brother was an important person to them when he was alive, why did they make promises to me and my family after his death? Why did they take me into their organisation for five years?” he asks.

Also read: ‘Damini’ to ‘Guilty Minds’ — Indian legal dramas go beyond ‘order, order’, wild meltdowns

372 hearings, 109 witnesses, over 15 judges

Khalid now works independently and has a criminal law practice of his own. He looks after cases related to Prevention of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO), domestic violence, and insurance, among others. Till 2015, he relied on Jamiat to handle the trial and the hearings. But since the fallout, he has been keeping track of the hearings himself.

In the twelve years since Shahid’s murder, the case has come up for hearing 372 times and judges have been changed a dozen times. Only about a dozen witnesses have been heard out of 109. The prime witness in the case is Inder Singh, Shahid’s clerk, who was present in the office when Shahid was shot dead.

According to Khalid, the chargesheet was filed within the statutory period of 90 days in May 2010. It named the four accused – Vinod Vichare, Pintu Devram Dagale, Devendra Jagtap and Hasmukh Shankar Solanki. Six others, including a former aide of Chhota Rajan gangster, Bharat Nepali, were named as absconding. They were all charge-sheeted for murder and criminal conspiracy under various sections of the Arms Act and the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999 (MCOCA).

The trial court dropped the charges under MCOCA in January 2011. The state filed an appeal in the Bombay High Court, challenging the dropping of the charge. While this appeal is still pending, the High Court has clarified that it has not stayed the trial.

After a chargesheet is filed, the court is supposed to frame charges against the accused and drop the ones that aren’t supported by enough evidence. However, the charges, in Shahid’s case, were only framed after seven years in August 2017 — a development that even the Bombay High Court found “surprising” in one of its orders.

Also read: MCOCA, conflicting evidence, 44,000 pages of confusion — 7/11 train bombing case drags

A wristwatch, a ‘special’ bed

In an order passed in August 2014, the trial court expressed its own frustration with the delay. The order noted that while the court was ready with the charges, the accused and their lawyers didn’t want them to be framed, citing this pending appeal on the MCOCA charge in the High Court.

In addition to the change in the judges and Covid, Khalid blames the delay on the several applications filed by the accused as well. Along with the bail applications, the accused also filed applications demanding a wristwatch and a different bed in jail.

In 2011, Hasmukh Solanki filed an application before the court, seeking permission to use a wristwatch for his personal use in jail. In another application, Devendra Jagtap informed the court that he had arthritis and needed a different type of bed in jail. Special judge V.V. Virkar rejected both these applications in December 2011, asserting that there was nothing to support their demands.

And this delay in the trial has since helped three of the accused get bail.

Vinod Vichare was granted bail by the Bombay High Court in 2012. Pintu Dagale was also granted bail in July 2015 — he had been in custody for more than five years and the trial had not even started yet.

Jagtap and Solanki also filed multiple unsuccessful bail applications before the trial court, the Bombay High Court and even the Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court rejected Jagtap’s bail application in 2018 after it found out that he had lied to the court about not having any past criminal record. During the hearing, the Maharashtra government told the court that there were as many as 10 different cases against him.

Solanki was finally granted bail in April 2022 — once again on the grounds of delay in trial.

However, one of the lawyers representing one of the accused in the past says that the delay can be attributed to Covid and the frequent change in judges in the case.

“Every time a new judge comes in, he or she adjourns every case by default at least once or twice, because it takes time to get acquainted with any case,” he explains. He also says that when he was appearing in the case, the prosecution often faltered in bringing the witnesses for examination.

Sumita, Jagtap’s sister, also blames the prosecution for the delay and says that it is “causing harassment to my brother.”

“He is unnecessarily behind bars,” she remarks.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)