A house of prayer next to a boutique. A coal truck that has been repurposed for a Christmas procession. And a roadside monument to Thomas Jones, a Welsh missionary Meghalaya never forgot.

These are just some of the striking frames from artist Tarun Bhartiya’s Niam/Faith/Hynniewtrep exhibition of 100 ‘constructed’ picture postcards with both contemporary and archival images of faith in the Khasi hills hanging at the BayArt Gallery, in Cardiff, Wales, this month (between 1 and 22 October) as part of a collaboration between Chennai Photo Biennial and Diffusion: Wales International Festival of Photography.

In 1841, Jones, a 31-year-old Welshman, went up the Khasi hills, present-day Meghalaya, to be a missionary. He would come down these hills eight years later, a rebel, to die in Calcutta (now Kolkata), hounded by the East India Company. Jones gave the Khasis – the majority tribes of these hills – a written script, translated part of the Bible, useful carpentry skills, and the knowledge of how to distil alcohol to treat wounds. But he had not one convert to his name. Jones, so goes Church lore, was more focussed on practical matters than in ‘saving’ the Khasi soul.

Missionaries that followed had better success in converting Khasis from their old faith, Niam Tynrai, but Jones perhaps set the “tone” of what is unique in the “Christian encounter” in these hills, says Bhartiya, a documentary filmmaker, photographer and activist, who grew up in Shillong.

Bhartiya stays in Meghalaya’s capital and is married into a Khasi family. His films include La Mana (Not Allowed, 2017), The Last Train in Nepal (2015, BBC4, Royal Television Society Award, Best Director 2015), and Jashn-e-Azadi (2007), which he edited. His current exhibition is an alternative window into thinking about faith, organised religion, its followers, and proselytisers.

“Missionary is not a popular word in India today. In the archives I looked through, I saw photos that somehow reinforce that image — they being carried up the hill on the back of the natives,” says Bhartiya. “And yet this image of a Sahib missionary is incomplete when it comes to Welsh missionaries in our hills.”

The Welsh pastors, from when Wales was colonised by the British, were sons of farmers and carpenters. It is perhaps his working-class origins that stirred Jones, when he saw Company officials exploiting the Khasis, and he “sided” with them.

Bhartiya’s exhibition also highlights another less-talked-about aspect of Christianity’s brush with the local population — the converts and pastors who accessed remote areas in the hills, which the missionaries could not. Check out the photo of U Larsing, Khasi evangelist, standing behind his mentor, Welsh pastor William Lewis, and his wife Anna. For a contemporary reference, there is the dapper Reverend J.R. Makdoh, wearing a cowboy hat standing with one hand on his horse and ready to set off for Sunday service.

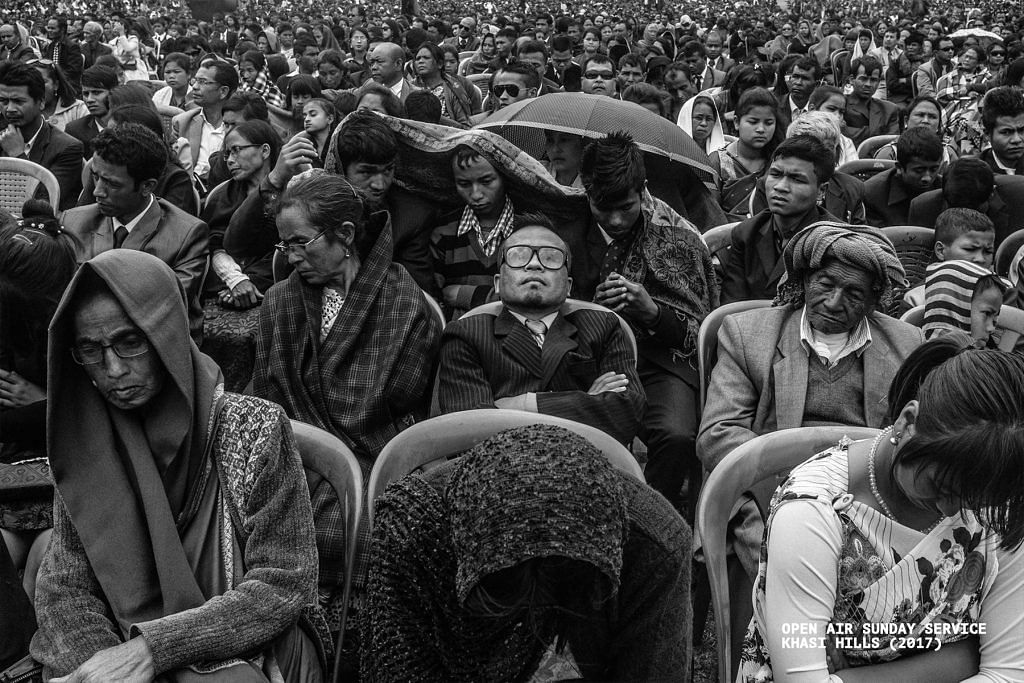

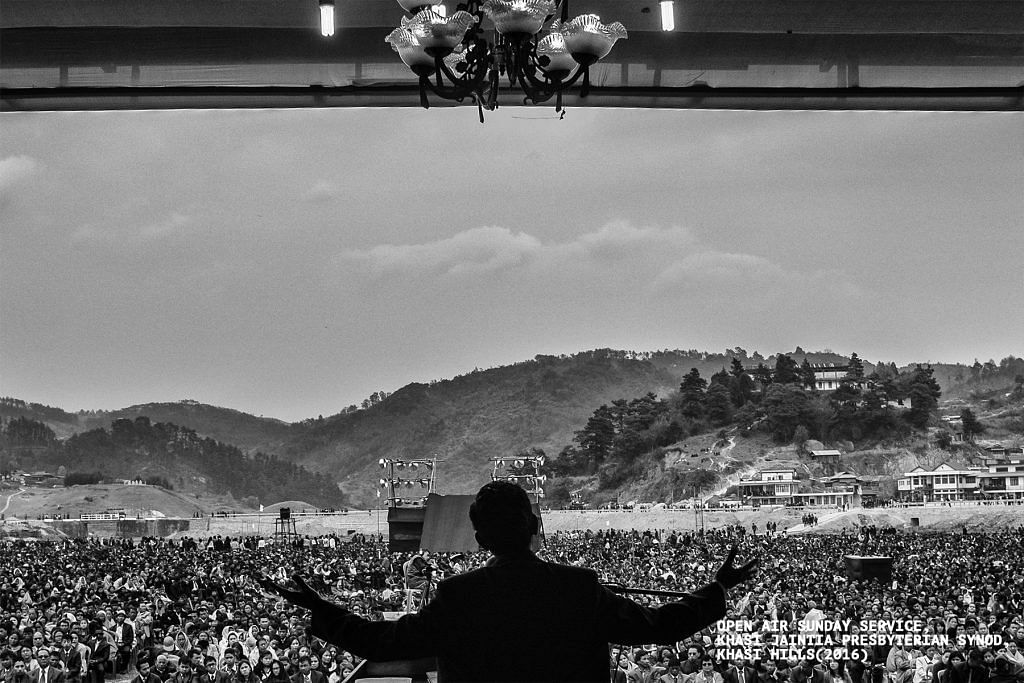

The exhibition of black and white photographs also maps how faith is not easily given up or followed. Bhartiya’s documentation from the last 14 years of Meghalaya, when the Khasi hills witnessed a wave of ‘Christian revival’, keeps that tension alive. If there are photos of a huge congregation in an open field, there are also photos with followers asleep during a church sermon. Children of families that follow the indigenous faith are seen waving the Seng Khasi flag, as are Christian children in the grip of religious ecstasy.

Also Read: Vijay Kumar, the art blogger & enthusiast who helped Modi bring back 157 artefacts from US

Christian Khasis and Niam Khasis

The Seng Khasi is a cultural and religious organisation that was formed in 1899 by the indigenous Niam Khasis of the “old faith” who followed the pre-Christian Khasi religion. A 2014 report in Hindustan Times, quoting a Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram (VKA) functionary, says that the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) “funds and supports” several independently run Seng Khasi schools in the state. VKAs are at the forefront of anti-conversion campaigns and they are “RSS-backed”.

Paia B. Synrem, assistant general secretary, Seng Khasi Kmie, Shillong, however, clarifies: “With like-minded organisations aligned to our ideology, we may have relationships but we maintain our independence. Our organisation was essentially built to protect and preserve our faith from attack on our faith by religious thoughts and ideas brought in by the British. But we are not Hindus though some of our practices are similar.”

The Niam Khasis too had their ‘revival’ when it began to intensify and expand its activities in the late ’70s and ’80s. 23 November began to be celebrated as Foundation Day in Shillong. The Seng Khasi organisation has by now more than 300 branches all over the Khasi hills, says Synrem.

Bhartiya’s curation suggests that the moving away from one’s ‘original faith’ did not happen in the Khasi hills through straightforward “conversion” or “coercion”, as missionary activities are set out to be by the Hindu Right. The exhibition also draws on the contemporary conversation on these topics by referring to Uttar Pradesh’s anti-conversion Bill in many of the photographs’ captions.

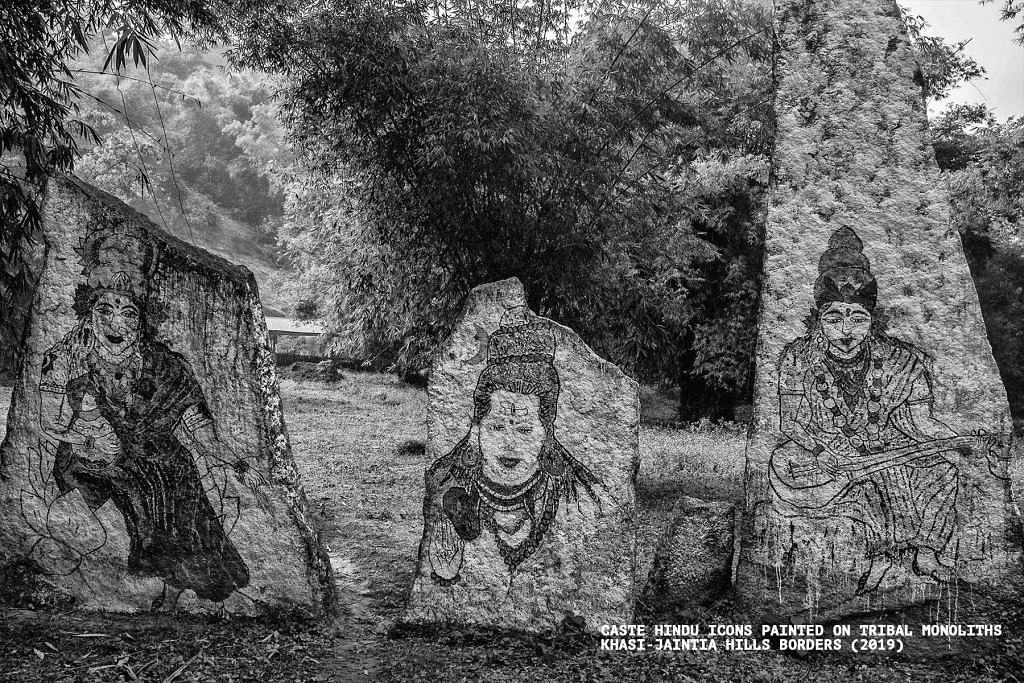

There have been attempts at rewriting socio-religious traditions from the other side as well. “Monoliths are a unique marker of Khasi-Jaintia secular and sacral history. They point to their ancient traditions,” says the filmmaker. During his documentation in the hills in 2019, he found monoliths that – he has featured one in his exhibition – painted over with Hindu imagery in the Ri Bhoi area of the Khasi Hills.

“In the Hinduised notion of faith, conversion is seen as an encounter between ignorant people and powerful missionaries,” says Bhartiya. “In the Khasi hills, however, converting to Christianity was a difficult proposition. Converts risked breaking traditional kinship and family ties. But even when they converted, they did not automatically accept the western Christian worldview. They could challenge even the missionaries if they saw that the missionaries did not hold up to the Christian values. Khasis want to be Christians on their own terms.”

Khasimon Phanbuh, a Seng Khasi community leader, who had been vice-president of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s women’s wing in Meghalaya in 2007, however, says the push for indigenisation or a Khasi cultural assertion among Christian Khasis (comprising about 75 per cent of Meghalaya’s population) actually came from “an indirect pressure” from its small but influential non-Christian Niam Khasi population (about 25 per cent).

Indigenisation also seems to be a result of the accommodation of various faiths in a single family that is uniquely Khasi. So, the push for Khasisation may have come from ‘within’.

Pastor Kysoibor Pyrtuh says his grandfather “became a Presbyterian by choice in his 80s”.

When writer and music producer K. Mark Swer’s grandfather died, his funeral rites were half Christian – in deference to some of the family members who were Christians – and half of the indigenous faith he was born into. “When his son, my uncle, died he was given a proper Khasi traditional funeral because he actively followed the traditional faith. Another uncle was given a Christian burial because he ‘followed’ his wife’s faith, though he never converted. There’s no big conflict. Lots of Khasi families have this mix,” says Swer.

Also Read: Stone Age tools, cave paintings discovered in Haryana could be clues to ‘prehistoric factory’

Reviving the revival

A greater challenge that is facing Christianity in the hills is faithlessness among the young, said Bhartiya. What is true for all organised religions is true for Christianity in these hills. This is why he was surprised by the signs of a ‘revival’ especially among the Presbyterians — mass hysteria, children declaring themselves prophets, being touched by the Holy Spirit, the seeing of angels, and daily full-house attendance at church — washing over the Khasi hills in 2006. The majority of Khasis are Presbyterians followed by Catholics and Anglicans.

“There is of course the historical reason, they were celebrating 100 years of the coming of Christianity to the hills. Deeply convinced of their relationship with God, the young were channelling the pain and tribulations of their community. As an atheist, I could have dismissed this event as ‘delusion’, but I chose to believe in their belief,” he says.

Writer Avner Pariat of Shillong, whose grandfather was a church elder, says many Church families were “astounded, quite shocked” by the unfolding of events. “Even now, there have been reports of attempts to sustain the revival in certain personality-driven religious cults.”

Revival is, however, no longer a mass phenomenon, adds Bhartiya, but “people keep praying for it. The search for salvation is, after all, a constant struggle.”

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)