New Delhi: Each time 17-year-old Ayesha got pregnant, strange images would blossom in her mind: a headless witch covered in blood; a giant, slimy snake wrapping itself over her home. Her first child was stillborn; her second one died a few hours after birth.

“Everyone in my family thought I got possessed by a demon when I was pregnant, and that is why my children died. They blamed me for what happened,” Ayesha, who was only 14 when she got married, says.

The mental torture became unbearable. One night, with Rs 1,000 in her small brown sling bag, she hopped onto a train leaving Gaya, Bihar, not knowing where it would take her.

She found herself at platform number 8 of New Delhi railway station.

Ayesha wasn’t the only child to have arrived here, alone. Every day, scores of children and teens like her deboard at New Delhi railway station, where close to 500 trains from all over India halt daily.

Many of them come looking for work, or friends, or simply to roam around the city. A handful of them hop on the crowded trains to find their mothers or grandparents and get lost along the way. Others do it as an act of rebellion.

Often, though, they are escaping from something: absolute poverty, extreme deprivation, various forms of violence, constant abuse, or simply unbearable pressure to perform well in exams.

Away from home, they think they can make a fresh start.

“I didn’t know where I wanted to go. I just wanted to get away from home,” Ayesha says, fiddling with a polybag containing biscuits and a book of jokes she bought from the platform. “I will find work and live independently.”

What becomes of children and teens like her depends more on luck, or lack of it, than anything else.

Some children simply disappear, even forever, perhaps into networks of trafficking, begging, prostitution, or child labour. Or, older children, not any better off themselves, take them under their wings and into a life of rag-picking and drug addiction.

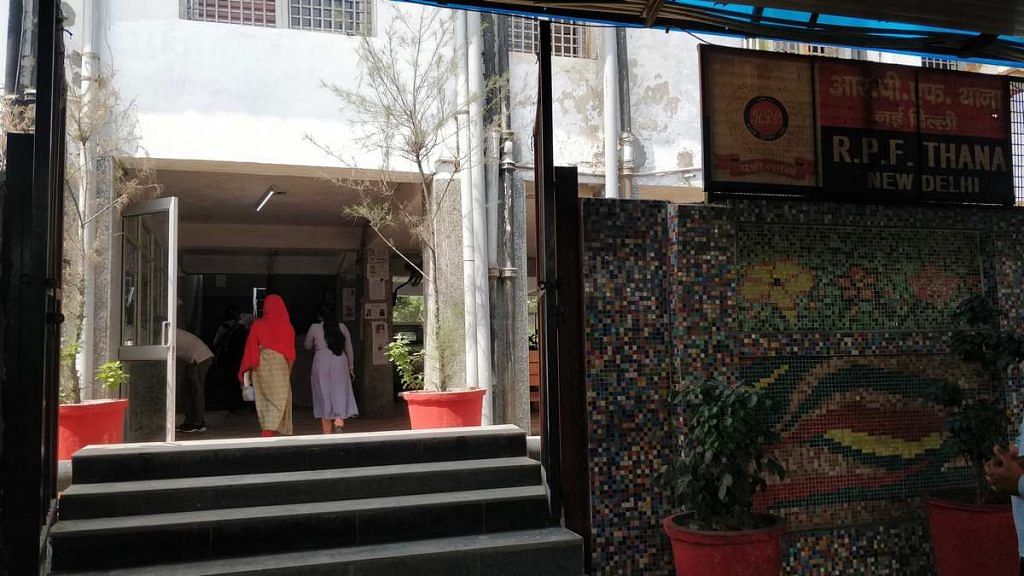

Some, like Ayesha, are spotted by dedicated teams of non-profit organisations, deployed at stations to keep an eye out for lost or runaway children. Called the Railway Protection Force Mitras, these teams work in collaboration with the RPF and the Ministry of Women and Child Development, acting as the authorities’ eyes on the ground.

Also Read: 2021, the year mental health cases exploded in small-town India

Looking out for the signs

Every morning at 8am, Yash Shishodia and four of his team members take their positions between platforms 6 and 9 of New Delhi Railway Station.

All of them work for the Bengaluru-based non-profit SATHI (Society for Assistance to Children in Difficult Situations), which has been rescuing children from railway stations across India since 1992.

Platforms 6, 7, 8, 9 are important, the team explains, because they see the highest rush of trains to and from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh — the two states from where maximum children are found.

Two team members stand on the overhead bridge that crosses all these platforms while the others take on patrol duty.

With their RPF-issued identity cards tucked in their belts, they look out for children walking aimlessly at the platform or who don’t have more than a small bag as luggage.

“The children who are alone mostly go to food stalls as they are hungry. They ask for work. In case we can’t spot them instantly and they spend a few days at the platforms, their appearance looks dirty, their clothes are ragged. These are clear signs to us that the child is alone and in need of help,” explains Shishodia.

Once a child is identified, the teams have to follow strict protocols. The first contact with a girl, for instance, can only be made by a woman team member. The staff also cannot coerce the children into going with them or chase them.

“The children sometimes get scared and start screaming. The staff is put in danger because the public gets suspicious,” says Ramanand Singh, who is part of SATHI’s New Delhi team.

Once a child is taken into custody, more hard work has to be done. The team must clear a mountain of paperwork, provide counselling, and present the child before the railway and local police stations as well as child welfare committees.

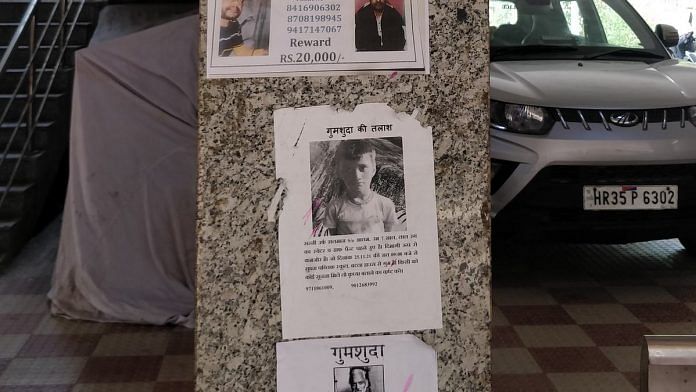

Tracing the families is also not easy if the child doesn’t have any phone numbers or doesn’t remember the name of the station from where they boarded the train. And with limited resources and fewer teams, the surveillance at the New Delhi railway station is not round-the-clock. Railways Childline, operated by the Ministry of Women and Child Development since 2015, also has a booth there, but all these efforts still need a boost.

If the parents can’t or won’t come instantly, the child is taken to an open shelter run by an NGO or to government safe homes.

Through it all, the teams are acutely aware that with every child they attend to, many others may, and likely do, slip through the cracks.

Indeed, according to estimates arrived at by SATHI, throughout India, about 60,000 to 80,000 children land up at various platforms each year and not all of them can be rescued.

Also read: 64% kids in rural India fear they have to drop out if not given additional support: Survey

Fractured families, violence, school pressure

Before Covid, about 30 unaccompanied children used to reach New Delhi railway station every day, which means about 900 each month, according to SATHI estimates based on week-long surveys.

However, not more than 250 children were found each month, despite the efforts of three other NGOs — Prayas, Salam Balak Trust, and EFICOR (Evangelical Fellowship of India Commission on Relief).

Rajshekhar M, deputy secretary, SATHI, says this means about 70 per cent of children who arrived at the station were never found. According to him, fewer children are currently being spotted at the platforms, but they still arrive regularly — seen or unseen.

Data collected by SATHI on these children shows that most of those who escape to big cities are Dalit or from other disadvantaged castes and close to 60 per cent of them are from poor families, usually from impoverished parts of the country.

“Jharkhand, Bihar, West Bengal, Eastern Uttar Pradesh are the areas of absolute poverty where there is a chronic migration of labour force to the rest of the country in any case,” Shanta Sinha, former chairperson, National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, says, adding that this impacts the children of these families.

“There are a lot of fractured families where one or both parents are migrating, there is not enough food and even if they are in the house, there is violence,” Sinha says.

In some instances, children are forced to drop out of school to earn for their family or they are burdened with the weight of being insurance for the older generation. In these stressed homes, expressions of love and tenderness are a scarcity, and beatings take the place of guidance.

“Children should not be burdened with maintaining the family,” Sinha says. She is currently working in Bihar to strengthen child protection committees at the gram panchayat level and training them to track each child to ensure they are safe and being cared for.

Also Read: Licensed to torture: How drug rehabs in Himachal use beatings to ‘treat’ addicts

Impulsiveness and rebellion a factor too

A survey by SATHI in 2019 indicated that children between the ages of 10 and 15 comprise the latest proportion of runaways, and that not all of them come from abusive homes.

“The children are in a rebellious age and most of their actions are impulsive,” SATHI founder Pramod Kulkarni, who retired from active work two years ago, explains.

When he first started working to rescue children, he says, there was a perception that they should not be sent back home to the same situation that they were trying to escape.

But, with over two decades of experience behind him, Kulkarni now holds a different view.

“Our data shows that abusive homes form a very small percentage of the cases,” Kulkarni says. “In most cases, the reasons can be addressed. When sent back, children stay united with their families. A new learning for us was that if the reasons are resolvable and the child can be put back with the family, then why not?”

Out of the one lakh children rescued and resettled since SATHI’s inception, only 25,000 could not be reunited with their parents and have been sent to government homes for long-term stay. The others have all been reunited with their families.

The NGO’s 2019 study also found that 99 per cent of kids who were reunited with their families between 2008 and 2009 remained at home and never left. Today, many of them live fruitful lives, pursuing careers in the army, or as artisans, technicians, and drivers.

‘Children should become the priority’

The focus should be not just on rescuing children but on preventing them from running away in the first place, Sinha says.

“The gram panchayats have to be given substantive amounts for the protection of such children and see that they are under care and protection from within the village. They can track the children. If these children are subjected to violence at home, either they can counsel the parents or remove the child from there and admit them into regular schools which have hostels, or to shelters which are closer to home,” she says.

And to fix the burden of poverty, regular meals at school and ensuring that the children don’t drop out are crucial, she adds.

“All these steps can be easily implemented… if only children become the priority.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)