New Delhi: The staging of the play Hunkaro at Delhi’s Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards or META festival just as Anubhav Sinha’s new movie Bheed released turned the weekend into one of moral reckoning.

The black-and-white movie likened migrant workers’ long walk home during the Covid-19 lockdown to Partition. And Hunkaro, raw and unsparing, forces the audience to confront their wilful blindness during that period. In both productions, India’s privileged are shown to be complicit in the migrant workers’ woes.

META fests have been prestigious cultural events for the past 18 years and are anchored by the culture outreach wing of the Mahindra Group and Teamwork Arts. This year, the weeklong offering mounted 10 plays from across India in half a dozen languages. Two of these, Hunkaro and Namak, carried sharp commentaries on the experiences that emerged during the pandemic.

“Everyone saw everything, there was no hiding. If we forget it and let people forget it, it would be a huge, huge mistake because there is so much to learn from that,” said Hunkaro director Mohit Takalkar, who is a part of the experimental Marathi theatre movement. “We should keep creating work about this misery and this suffering. So, time and again, as we go back and look into the mirror, we’ll have to face these questions.”

Hunkaro is nominated for several META awards, including for best direction, acting, original story, and design.

Also read: India’s gaanewalis come alive with songs and storytelling – Begum Akhtar to Shobha Gurtu

‘Maybe you are the pests’

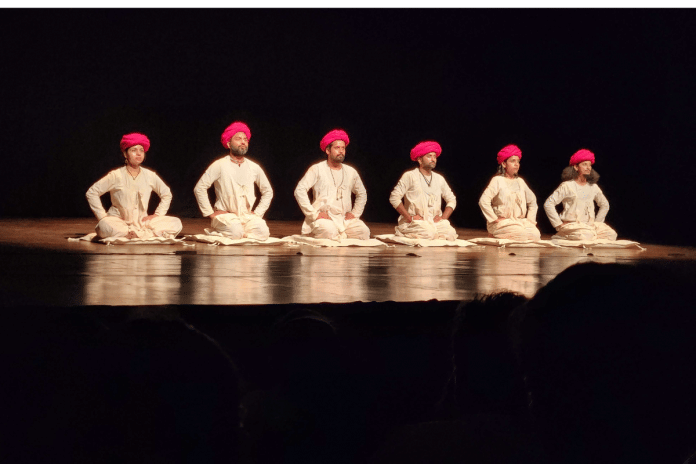

Nothing about Hunkaro is easy — least of all its languages. Everything is designed to discomfort the viewer. The actors remain seated on the floor in stark stillness throughout the play and don’t move about much. There are no props, no artifice except for the floor cushions they sit on. The stories are wrenching. They speak in dialects that most in the audience said they didn’t understand, except for a few words. Their acting resides in pure storytelling power.

The play is a multi-lingual production — in Marwari, Hindi, Haryanvi, and Awadhi. The 85-minute play, a collaboration with Jaipur’s Ujaagar Dramatic Association, is set on three stories by Vijaydan Detha, Arvind Charan, and Chirag Khandelwal.

Khandelwal’s Giddh shows a migrant worker befriending a strange half-crow-half-vulture on his walk home. The crow stands for survival, the vulture for death. And hanging perilously between the two is the worker’s hope. The story is introduced by an RJ who addresses listeners working from home, downloading new recipes on YouTube, and beating plates and vessels on their balconies, while the workers are walking 923 km in the scorching sun. And he calls the story “He walks” (Woh Chalta Hai).

The actors force the audience to participate in the workers’ walk to shake them out of apathy. Who is walking, the actor asks. The audience replies. Why is he walking? The audience is forced to engage. What is the title of the story? The actors also urge the audience to give out verbal affirmations throughout the play — the meaning of ‘hunkaro’ — because one actor tells them it is ‘a signal of transaction’.

The story, told in Awadhi, is excruciatingly detailed and slow. Just like the walk would have been. Braving the summer heat, sleeping hungry under the truck, having disturbed dreams, staring at the Aadhaar card number and the old bearded man on hoardings, counting dead bodies by the thread tied on their toes, and looking at the sun through his wife’s x-ray films.

And when the workers are sprayed with disinfectant, he asks the bird: “Why are we being sprayed with pesticides? We are not crops.” The bird answers: “Maybe you are pests then.”

Charan’s story Maai is about two brothers who leave a Mumbai chawl during the lockdown for their village in Rajasthan. They leave behind a physically disabled mother. The brothers are eaten away by guilt all along and a hope that she will make it. A year later, they start for Mumbai again to rebuild their lives.

But what grounds the two stories is Detha’s Asha Amar Dhan, which shows the starting point of a villager’s decision to leave home for work in the city. This decision is laced with hope but also loss. It is a Marwari story about a couple who leave their drought-ridden village for the big city. They lock up their children and leave them with a bit of food. The children hope the parents will return by evening, the father hopes someone will rescue them, and the mother hopes she will find wealth in the city.

“Mohit Takalkar is always pushing the envelope of theatrical experience through form, content, and presentation,” says Danish Husain, founder of the theatre company The Hoshruba Repertory.

Also read: Making art is a hugely political act in itself: Sitarist Anoushka Shankar

Penny drops for audience too

Hunkaro highlights how people lost the capacity to listen during the lockdown. That is why it begins with a Marwari play, challenging the audience to pay closer attention in the hope of understanding a few words here and there in order to make meaning.

The actor, who is also a storyteller, asks the audience if they understood the Marwari lines. Viewers say no. He then tells them that the words are simple, some are similar to words in other languages, others are onomatopoeic. Only if languages are spoken and heard will they live on, he explained.

Using unfamiliar dialects in front of an urbane audience is also a way of reinforcing the unknowability of the workers’ experience. Takalkar forces the audience out of their passivity to become active participants in the play’s meaning-making.

“I don’t know about others, but I am also telling myself that I am very much complicit in the migrant workers’ misery,” Takalkar says. “I was also showing fake concern about these things happening around. After that, the penny dropped for me at that time —oh my God, my life is so privileged.”

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)