At a luxury condominium in Noida, a Resident Welfare Association called an emergency meeting at 7pm. The agenda? How to deal with the menace of viral social media clips alleging harassment by those who either live or work at the township. And they were not even talking about Bhavya Roy.

The RWA was following up on a resident’s claim of harassment for feeding stray dogs. The fight wasn’t filmed, but the resident uploaded a video detailing the incident for his 13 lakh followers on YouTube.

The gated community had cause for concern. A clip from the neighbouring Jaypee Greens Wish Town township of resident Bhavya Roy hurling abuses at security guards had gone viral over the weekend.

While class conflict in gated societies isn’t uncommon, the new wrinkle isn’t just between homeowners and blue collar workers. It is also between the old and the new rich, and between the working class and the newly wealthy.

But both the working class and the upper class point fingers at the same group of ‘troublemakers’: the newest among the new rich. They arrive in these wealthy, rarified, self-contained condos after having made money from businesses like “dry fruits and paan” — a code for contempt. And they live a cocooned life — they swim, play, eat, drink, shop and bank inside their gated communities. Most of their only daily interactions are with the domestic workers and security guards.

It doesn’t matter that Bhavya Roy is an American-university educated lawyer. Workers and residents alike have written her off as “new money” who brought disrepute to their residential colonies.

A security guard in the complex Roy lives in says she was “probably drunk” — and that she was only renting a condo and didn’t own one. “The kind of people who live here are all VIPs, people who come from good backgrounds,” the security guard said. “They don’t behave like this.”

And among the residents, there’s an acceptance that things are changing.

“This is Noida. Lots of people come from small towns in Uttar Pradesh and buy or rent condos because they want a better life. They come with big money and the same small-town mentality,” said a 27-year-old investor who moved from Kanpur to Noida’s Jaypee Golf Greens.

Also read: The Great Gate Rage—Noida’s security guards are up against a new class war

Condo culture: convenience, comfort, control

Towering luxury condos line roads like Gurugram’s Golf Course Extension or the Noida-Greater Noida Expressway.

They come equipped with their own supermarkets, restaurants, theatres, bars, and schools. One luxury township even has a private art gallery inside. They are fully functional ecosystems, offering endless convenience at a price.

Condos are also attractive to working professionals with young families who can be at work and let their children roam free in a gated colony. Developers are also building ‘affordable’ condos priced at the lower end of Rs 1 crore, aimed at this younger generation.

“The big plus is that there’s a sense of community and security,” said K. Gyandeep, who has lived in DLF Magnolias in Gurugram for the past ten years and is a member of their homeowners board. “The facilities like the restaurant and clubhouse are also brilliant.”

He added that incidents like Roy’s assault of guards are rare. “Obviously there might be rude people, but they would have done the same in Punjabi Bagh. This isn’t condo culture, it has more to do with what she’s like as a person. Generally people are friendly and courteous.”

Living in a gated community has many benefits, including how everything is catered to residents. The housing society employs labour like gardeners and handymen. One resident of a super luxury condo in Gurugram said she was extremely grateful to the housekeeping team that came to help at 2 am when a water backlog caused her bedroom to flood.

The goodwill — when it exists — seems to flow both ways. Savita, a domestic worker who lives in Jaitpur village in Greater Noida and works at two houses in Noida township, said she has never experienced any rude behaviour — and that she is actually paid more than earlier, because her expat employers can afford it.

Security guards similarly demur when asked about incidents of “gate rage.” The standard answer is that it does happen, but rarely.

Also read: India’s democracy goes beyond the last mall in Noida. Rural feudal rich are feeling the pinch

Changing demographics

Everyone agrees that Bhavya Roy is an extreme case, and not indicative of the kind of people who live in condos. But everyone also agrees that the demographic of people now coming to live in condos is changing.

High property prices in Delhi have been a catalyst for families looking to sell ancient, ancestral homes and move to sleek townships. Paying a high maintenance fee for a condo is preferable to maintaining havelis or kothis, according to residents.

But workers and older residents are somewhat disdainful of the “new” families choosing this life, coming as they are from successful businesses of their own instead of riding on the reputation of generational wealth.

Wealth allows access, but how the wealth was acquired is also under scrutiny now.

“People are moving in from areas like Punjabi Bagh,” said a resident at DLF Camellias, a gated community in Gurugram advertised as ‘Ultra Luxury Apartments and Penthouses’, the price of which is provided only ‘on request’. Punjabi Bagh is a locality in West Delhi — which is often stereotyped as loud, ostentatious and crass.

“Post-covid, there’s been a shift. The expat population has come down, and more apartments are empty, so landlords want their properties to be leased,” says Gyandeep.

Pointing to it as a mismatch, several residents said newer entrants to fancy gated communities like throwing parties to “show off” their new homes. Joint families who move from their ancestral homes into condos find themselves emulating their previous lifestyle. Some families invite relatives and loudly conduct walking tours of the colonies, or book the clubhouse for special events.

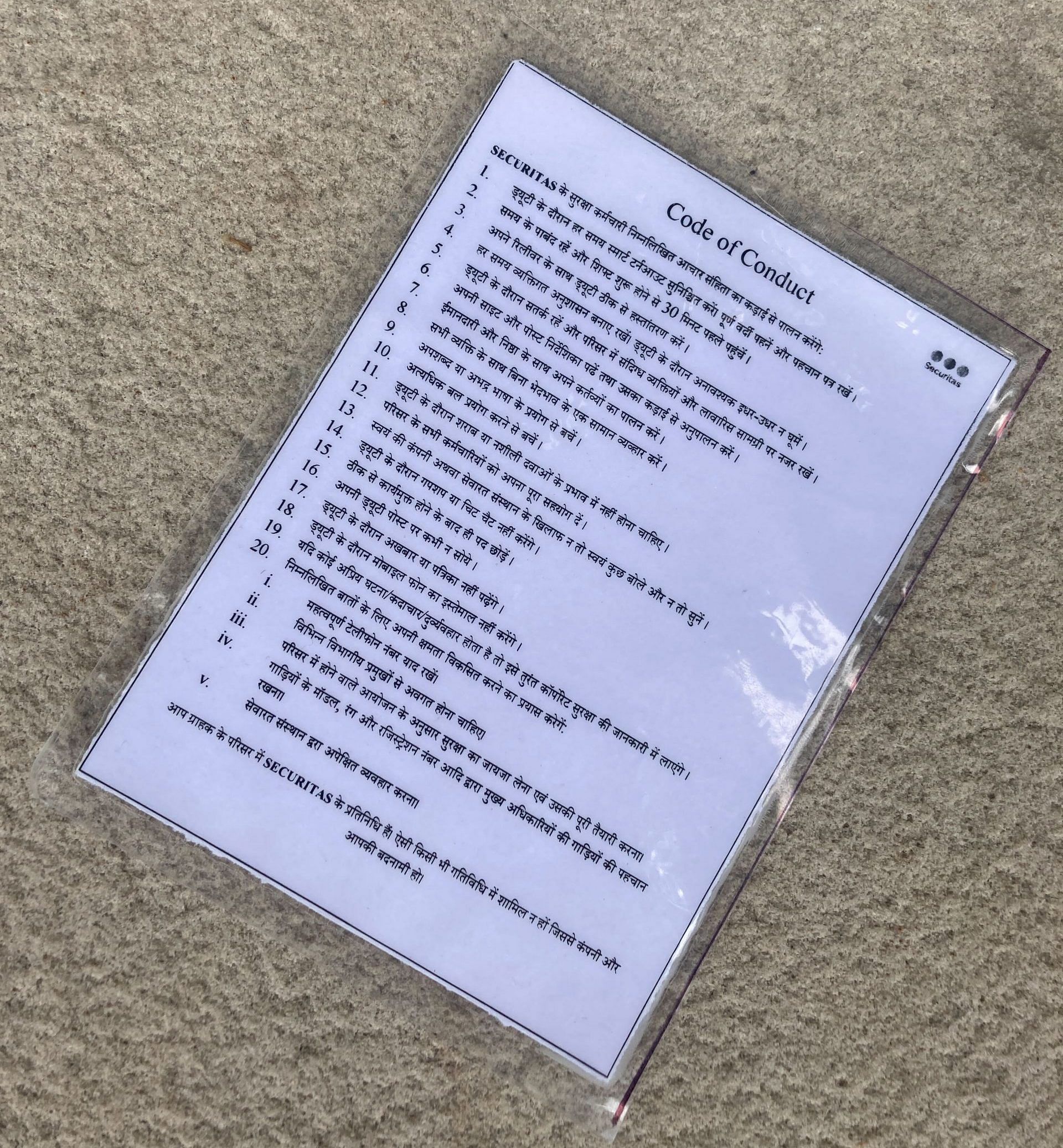

This might fly in residential parts of Delhi, but apartment complexes have unwritten codes of community conduct for residents. Sometimes, they also have written codes of conduct for the staff.

“They don’t have the civility of living in a condo,” said one longtime resident of DLF Magnolias. “The easier the money comes, the less people care about how they come across.”

Amit, a security guard, had the same theory about such residents. “People who got rich recently have ‘attitude’,” he said. “They don’t treat us badly, but we can tell. With other residents, at most they won’t return our greetings.”

A Swiggy delivery person in Noida, originally from Aligarh, also said that people who suddenly “emerge from the ground as rich” are the ones who don’t adjust their old behaviours to their new lifestyle. He has never been insulted by his customers while making deliveries — and good luck to those who try, he said. “I myself come from these areas.”

Also read: Noida vs Gurugram race is heating up. All eyes on Chautala’s job quota and Yogi’s Jewar

‘Cultured’ vs rich

This perception of the “new” new rich hinges on and is guided by age-old notions of class, culture and caste.

“The social mobility of certain middle-castes from agrarian backgrounds and provincial towns into these predominantly upper-caste enclaves unsettles otherwise masked caste hierarchies,” said Dr Sai Balakrishnan, associate professor of city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley. “Subtle and not-so-subtle caste markers suffuse our built environment, and enclaved living is no exception.”

“India’s upper-castes have long deluded themselves as being cosmopolitan and casteless moderns, and the language of “new money” becomes an idiom for protecting caste privilege without having to call it caste,” she added.

The politics of respectability plays a big role in this, reinforcing the established hierarchy of who is to be considered respectable and who isn’t. By behaving “crassly”, a wealthy person loses the innate, unearned respect they get simply for being wealthy. Losing temper and showing aggression — especially when captured on camera like Bhavya Roy — is therefore immediately seen as déclassé.

“Culture and education aren’t the same,” said the 27-year-old investor in response to Bhavya Roy’s educational background. “Money plays a big role in both, but so does upbringing.”

Answering enquiries about neighbours like Roy is also proving to be a sticking point. “It’s embarrassing to have the police come and ask you questions about your neighbours when they’re respectable people,” said the vice-president of a Noida RWA. He’s considering floating the idea of hiring female security guards to deal with future unruly incidents involving women residents.

Cultural capital plays a huge role in determining one’s status as ‘upper class’, according to French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Upper-class ‘taste’ and ‘aesthetic’, itself a bourgeois understanding, are characterised by highbrow choices of art, literature, and clothes — all broadly accepted as “good taste,” as opposed to working class and lower class preferences, which are characterised as “bad taste” or “vulgar.”

This makes class mobility all the more obvious: being rich might grant you access to the upper echelons, but liking the ‘wrong’ movies, songs, books, clothes or makeup won’t bring you acceptance. This is similar to how elements like accent, address, and attitude are sometimes used to distinguish “old money” from the new.

Like Bourdieu wrote, “Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier.” And in Delhi NCR, where wealth is flaunted and judged constantly, how you are classified can make all the difference.

This article is part of a series on the class wars in Delhi NCR. Read all here.

(Edited by Prashant)