Safoora Zargar is learning to deal with the pain of losing friends and encountering online hate. Nargis Saifi hasn’t heard her children laugh in a long time. And P. Pavana watches her father tackle one debilitating disease after another. All three women have one thing in common: they have interacted with the police, prison authorities and the judiciary in the past two years, either as political prisoners themselves or on behalf of their loved ones.

Their stories have a constant sense of anxiety about financial security and social stigma. The lack of adequate medical care and neglect in prisons is another. Just thinking of how all this will end is adding to the mental toll.

“I will come out, won’t I? Is it going to take decades?” Khalid Saifi asked his wife Nargis in jail. “I did not know how to give him hope,” Nargis tells me. Khalid, the founder of United Against Hate, was arrested in February 2020 following the Delhi riots. He has been in jail since, under charges that the family says are ‘fabricated’.

“One day we will get justice. But until then, we have to suffer the collapse of our business, the suspicion with which people look at us or the fact that my children are growing up without their father. Who will be accountable for our struggle? I am sure Khalid will be acquitted, but our debt will remain on the judicial system,” Nargis says.

Khalid Saifi please इस विडीयो को सुनिए

और मेरे साथ मेरे शौहर के लिए उन को सही इलाज़ मिल सके उन के लिए आवाज़ उठाए।।

मेरा साथ दे।।#staystrongkhalidsaifi #KhalidSaifiKoRihaKaro #ReleaseAllPoliticalPrisoners pic.twitter.com/bIiJWWqUBo

— Khalid Saifi (@KSaifi) July 23, 2022

Safoora was arrested in April 2020 under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act in connection with the anti-CAA protests and spent about two and a half months in jail. Though she is out on bail right now, it could be a temporary reprieve. The arrest of human rights activist Teesta Setalvad, one of the petitioners who challenged the clean chit to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the 2002 Gujarat riots, is a reminder that these cases just ‘never go away’.

Also read: Indians will regret their silence over Modi’s ever-growing list of political prisoners

Poor medical care

As if the trauma of being thrown into prison under the draconian UAPA isn’t bad enough, the inhuman conditions inside make the ordeal unbearably painful. All three women spoke about the abysmal condition of the prisons, poor infrastructure and the lack of basic medical care.

“When we last went to Taloja jail, there were three doctors for more than 3,000 inmates, two of whom were ayurvedic practitioners while the third specialised in homeopathy. Two of the three doctors were retired, and not one had an MBBS,” said Pavana.

She has been fighting for her father, 84-year-old Telugu poet Varavara Rao, to be granted permanent medical bail. Rao is an accused in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon violence case and was arrested under the UAPA for allegedly plotting to assassinate Prime Minister Modi.

The death of Jesuit priest and tribal rights activist Fr. Stan Swamy is a reminder of just how bad things can get. Before his death in April 2021, the special NIA court had rejected Swamy’s application seeking bail on medical grounds. His death has been described by social activists, human rights organisations, and his family as ‘institutional’ and ‘judicial’ murder.

Varavara Rao, who was granted interim medical bail in February 2021, has been denied permanent bail. “If he is sent back to jail in his present condition, I fear that his health may worsen. The doctors suspect he may be suffering from dementia and early stage Parkinson’s,” said Pavana.

“Prison is for reforming people. But those in the ruling class clearly see it as a place of punishment. There are so many rights available to the undertrial prisoners, which even the authorities with the jail manual don’t know about,” Pavana added.

Safoora Zargar described Tihar Jail as a prison for women working under the tenets of a male prison. “It is difficult for a pregnant woman to lie on the floor. There are no basic facilities like prenatal and postnatal care for women.”

Their experiences in prison are contrary to the landmark 1979 Supreme Court ruling. The court had held that those imprisoned do not lose their fundamental rights. However, Safoora alleges that human rights violations are taking place inside the jail on a daily basis. “Violations we don’t even dare to talk about.” Since coming out on bail, she has been trying to bring to light the lack of healthcare for prisoners.

Also read: Is ‘freebie’ a disease? What SC hears is out of sync with poor India’s logic of democracy

The impact on children

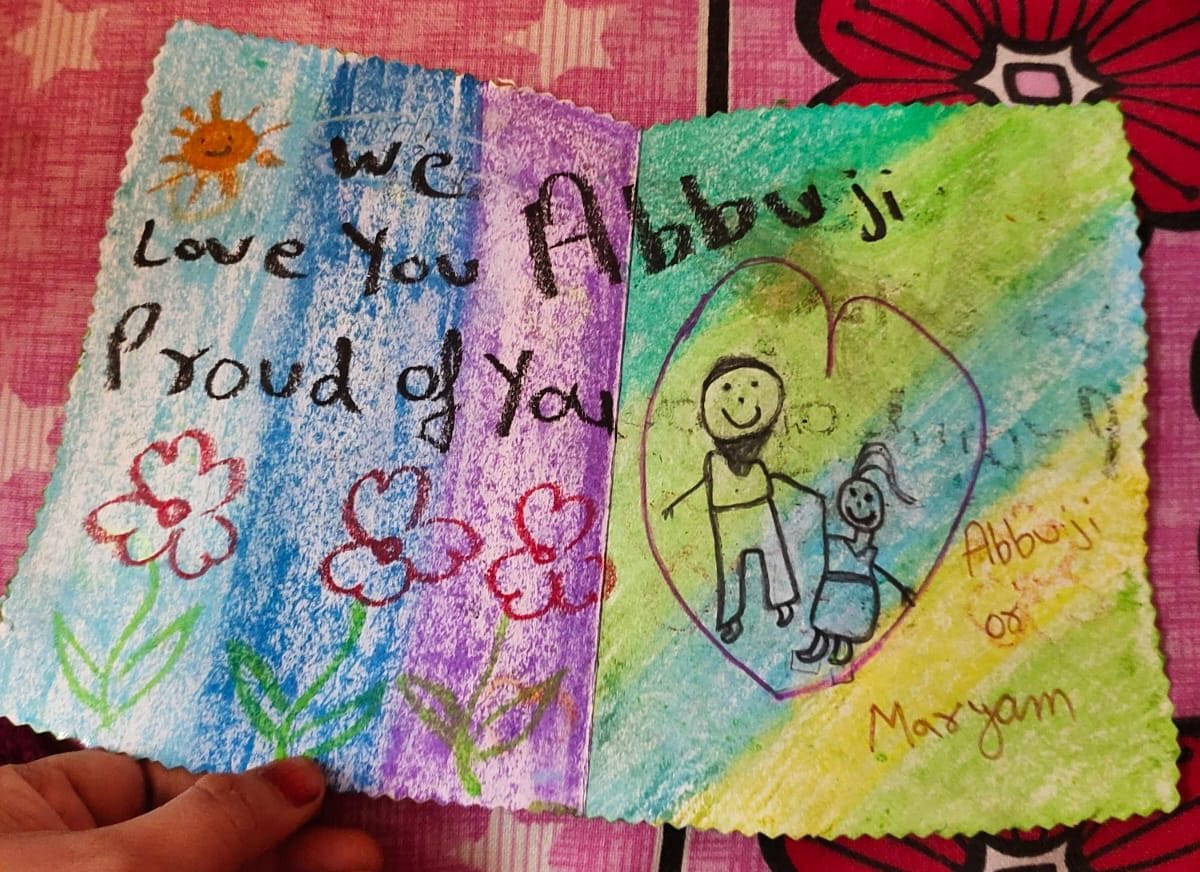

Empathy is a rare currency within the legal system and children are often left confused, if not traumatised, by the entire experience. When they meet their father Khalid in court during the hearings, Nargis’ three children immediately rush to hug him or hold his hand. It’s natural. But according to Nargis, policemen on duty stop them, sometimes physically prying the children’s hands from their father’s grasp. “The kids ask me, ‘What kind of danger can Abbu have from us?’ What should I tell them?” says Nargis.

Nargis tells her children that the police are only doing their job. “I explain to them that the cops are protecting their father from some bad people. I always tell them that we need to trust the administration and the courts,” she adds.

Her attempts to protect her children by restricting their access to news doesn’t always work. Though she imposed a blanket ban on watching television at the time of her husband’s arrest, her eldest son found videos on YouTube. “He came running to me with one question. ‘Did my father really do all this?’” says Nargis.

She faces stigma and judgement as she single-handedly raises their three children in Khalid’s absence. “When Khalid’s bail application before Eid was rejected, my children lost their hope. They have become even more silent now.”

The system also doesn’t take into account how a parent’s incarceration can negatively affect a child’s behaviour—its social, emotional and psychological ramifications. Researchers from the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice in the United Kingdom found that due to financial constraints, children are often unable to participate in regular activities. Some caretakers admitted that their wards had sealed themselves off from the rest of the society.

Pavana, too, was saddened and frustrated by the lack of empathy within the system. When her children had gone to meet their nana (grandfather) in the Pune jail, an official there denied their request saying only ‘the son’s children’ were allowed and not ‘daughter’s children’. “Every prison seems to have its own rules,” she says.

Also read: Bulldozers go after ‘illegal encroachments’ from MP to Delhi, but the law requires a notice

Toll on mental health

These experiences take a toll not just on their physical health, but also on their mental well-being. The ‘stigma’ of being in jail never leaves, and the onslaught from social media never lets up.

Nargis, for instance, has been open about her constant battle against suicidal thoughts. In a social media post, she wrote: If you really need to kill then kill me, my children and Khalid in one go. Why are you forcing us to die bit by bit?”

Every time Safoora consults a doctor and reveals her medical history, she can’t help but worry about their reaction. “What will the doctor think of me? Will she consider me a criminal? These are the thoughts that run through my mind,” she says.

After Safoora was arrested, a Hindutva group shared fake photos that were pornographic in nature on social media. Though the videos and photos were proven to be doctored, she is still attacked through it. “Even today when I share my opinion on some social media platforms, these people keep targeting my marriage and my child,” she says.

An Amnesty India report shows that Muslim women politicians in India have been subjected to 55 per cent more trolling than others. According to Safoora, the way Muslim women are being subjected to trolling reflects a deep-rooted hatred towards them. “This dehumanisation of Muslim women is happening all around us. It is being carried out in an organised and systematic manner,” she says.

In these bleak times, the kindness of friends and strangers are a beacon of hope. Nargis said her husband’s business came to a standstill when he was arrested, but friends helped them financially. NGOs such as United Against Hate help families in need of financial assistance, while lawyers and activists reach out with valuable insight and legal help. It is these acts of kindness along with their commitment to the truth that keeps them going.