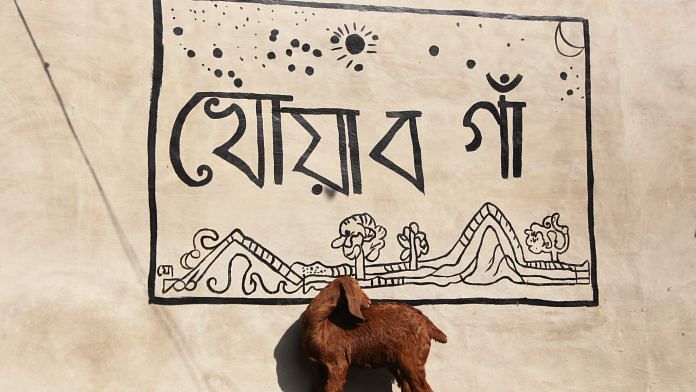

Lalbazar, Jhargram: Five kilometres from the Jhargram town in West Bengal lies a small village named Lalbazar. Surrounded by a dense forest of Sal trees, the village, home to the Lodha tribal community, has 13 houses, 11 of which have been painted by children. But the villagers are not satisfied with the hamlet’s name, and scholar Sibaji Bandyopadhyay has a suggestion: let’s call it Khwaabgaon (the village of dreams).

The paintings on the wall do not conform to any traditional or known form of art. Children aged between four and fifteen drew them using nothing but their imagination. The paintings are an imitation of the life in jungle.

A model village

It all began when artist Mrinal Mandal, a native of Jhargram, visited Lalbazar in 2014. He found the location extremely calming, silent and raw. “The village has only one road to go in and out. It’s small pocket with no disturbance, and an ideal environment for artists to work,” Mandal said.

In 2018, artists from different parts of West Bengal started visiting Khwaabgaon. While children were taught painting, women were taught how to sew qulits and men learned Katum Kutum, an art form introduced by Abanindranath Tagore, popularly known as Aban Thakur (nephew of Rabindranath Tagore). Aban created sculptures from discarded tree branches and roots, seeds of fruits, drift wood and leftover, unwanted wood. These items were sold in the two shops set up by the villagers while some were exported.

Apart from this, mime, terracotta, 3D painting, Pattachitra, Galar Putul, Taalpatar Sepai, and more modern and contemporary art form workshops were conducted in the village.

“We want to teach the kids the old art forms that have lost their relevance. Our idea is to make this village a platform for contemporary and traditional artists to come together so that this can be turned into an art village. This initiative has reached somewhere, but we want more to happen,” Mandal said.

“Right now, we are conducting a Dhokra (an ancient metal art form) workshop in the village”, Mandal added.

Dhokra is a skilled labour where artists spend days moulding shapes and designs in brass. The work started in 2021. After almost a year, the furnace was lit on Christmas day.

Mandal, the mind behind the concept, wants Khwaabgaon to become a model village that would inspire others.

Currently, Mandal’s initiative receives no funding from the government or private firms. Members of Chalchitra Academy, a non-profit organisation, provide funds to the project.

A tourist attraction

Villagers of Khwaabgaon are happy with the art project. Although it has not helped the tribals in any major way, the project has put the village on a map. Tourists from Kolkata and nearby areas have started coming to Khwaabgaon, which has become a ‘must visit’ place when travelling to Jhargram.

“My husband works in Jhargram. He heard about this small village that has houses with walls painted on them. Normally, we do not see such houses in our busy city lives.To reach this location we have to cross a jungle. It was picturesque. For a moment we thought we were on a jungle safari. When we saw the painting, we did not realise they were done by children. They were beautiful,” said Sangeeta Chakroborty, a tourist.

The money collected from selling the artefacts or the donation from visitors is put in the village bank – Tahabil. The villagers can take loans from Tahabil and pay back without any interest.

There were health campaigns for villagers as well and all houses now have functioning toilets.

Artistic kids

Khwaabgaon’s children learned to draw animals, trees, humans, and their existing surroundings. Fifteen-year-old Sikha Ahir painted deers, tigers, trees, and nature on the walls of her house. “I saw deers in the park and the rest of the elements were inspired from books,” she said.

Children observe elements in their natural surroundings, their lifestyle and draw them on the walls. Class 8 student Deep Mallik once saw villagers going on a hunt. He drew that on the wall of one of the houses. Mrinal Mandal said that the artists have taught the kids the study of nature and the kids replicate it on the walls.

Kamal Karmakar, a resident who has lived in Lalbazar for over 60 years, said the houses look colourful and pretty now.

Every year during Kali Puja, the walls are washed and painted aftresh. The project did not stop during covid.

The project has helped other artists too and revived forgotten art forms. Amal Karmakar, whose family has been involved in Dhokra art creations for generations, had come with his family to Khwaabgaon for the workshop.

“Our family has found this village and its people quite enticing. It is also a great place for us because the solid wax needed for the design is easily available here,” Karmakar said.

Lodha tribe

In the 1870s, the British government introduced the Criminal Tribes Act, which criminalised entire communities. This Act restricted the movement of people.

Sabars were one of the Lodha communities that were categorised as habitual criminals. Although the Act was nullified after India’s independence, the stigma it created about tribals remained for years.

Lodha tribals are forest dwellers, most of the villagers are daily wage labourers, or depend on forest and livestock for their livelihood.

Prashant Rakshit, director of Paschim Banga Kheria Sabar Kalyan Samiti, said that crimes were prevalent everywhere. There were criminals among Sabars as well, but not all. However, the stigma of being perceived as thieves continued.

“Socially and financially weak, Lodha tribes resorted to crime as a result of no employment. Over the last decade, the stigma has been diminishing. The tribals are counselled and are provided with alternative jobs. Major change has been brought by the young tribals, who are shuttling and migrating to other states for jobs,”

Khwaabgaon is located in a district with a vivid history of violent Maoist insurgency. Over the period, conditions of tribals have significantly improved. Once tagged as habitual offenders, the community has grown. And the young Sabars of the Lodha communities are growing up as artists.

(Edited by Prashant)