Babur’s daughter Gulbadan Begum wrote the Humayun-Nama. Nur Jahan, the 20th wife and consort of Jahangir had coins minted with her name on them, rescued her husband from the rebel leader Mahabat Khan, and was a dominant force in the Mughal court. Maham Anga, Akbar’s chief wet nurse, was a key political player during his reign. Women of the royal Mughal courts wielded power —both political and financial—but their achievements are often overwritten or underplayed by the overtly male perspective of history.

“History in the past has been seen not just from a masculine lens but from the eyes of the ruling elites. Kings have been described more than the queens, and among the queens, an archetype of a warrior queen echoes more than any other, as if the queen is acceptable in history only if she has fought the battles,” Queeny Pradhan, professor and author of Ranis And The Raj: The Pen and the Sword, told ThePrint.

While their lives may be obscured by stories of emperors, armies and conquests, the monuments Mughal noblewomen commissioned still remain in Delhi—a reminder of their contribution to the empire’s cultural legacy.

Also read:

Khairul Manazil

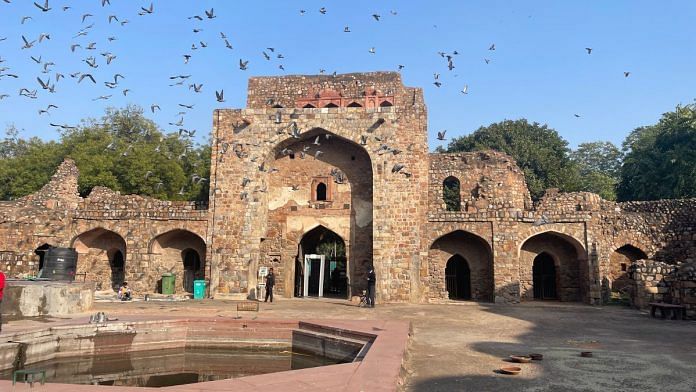

Right across Delhi’s Purana Qila, which Humayun and Sher Shah Suri built in the 16th century, stands the Khairul Manazil, a crumbling memory of one of Mughal history’s most powerful women—Maham Anga.

Now derelict, this mosque was built by Maham Anga in 1561, roughly 23 years after the Purana Qila. While it looks like a typical Mughal monument from the outset, its interiors are heavily inspired by Delhi Sultanate architecture. Anga was more than Akbar’s wet nurse; she was his furiously ambitious foster mother, often advancing her own agenda through her biological son and Akbar’s foster brother, Adham Khan. She was also a teenage Akbar’s political adviser and de facto regent from 1560-1562.

“She practised a certain sense of domination in the State from 1560 till her death in 1562. The time period shows that the foster mother of Akbar could find ways to get hold of the state machinery to concentrate power in her own hand,” Lubna Irfan, researcher and Assistant Professor at Aligarh Muslim University, tells ThePrint.

The Khairul Manazil opens into a wide courtyard surrounded by classroom-like structures, indicating that, apart from worship, it was intended to be a place of learning.

“Architecture was used throughout the Mughal period as a means of expression of power and asserting authority amongst the common masses,” added Irfan.

A well sits in the corner of this open courtyard, which is just as old as Khairul Manzil and functions even today. “This well is 30 feet deep, and people from all over the country come and bathe in it sometimes,” said the monument’s caretaker, who refused to be named.

Also read:

Mubarak Masjid

Even residents, for the most part, are unaware of the Mubarak Masjid in Old Delhi’s Chawri Bazaar. It was commissioned by Mubarak Begum, a famous courtesan who became one of the 13 wives of Resident Major General Sir David Ochterlony or “Loony Akhtar”, as he was popularly called.

A steep set of stairs running through a cluster of shops leads to this earthen-red mosque with three striped domes and three tombs.

Ochterlony was appointed to the Mughal Court under Emperor Shah Alam II during the early 19th century. He was famous for his eccentricities, such as taking long walks along the Red Fort with all 13 of his wives or frequently hosting dance parties at his residence.

Mubarak Begum, who started her career as a small-time nautch girl, was supposedly the General’s favourite wife. For a courtesan to commission a mosque is something most people would consider revolutionary even today. Mubarak Begum did just that in 1822, but couldn’t escape criticism.

“Mubarak Begum was also known as Generalee Begum, and her masjid was popularly known as Randi-ki Masjid (prostitute’s mosque) at the time,” explains Shah Umair, a history enthusiast, numismatist and founder of creative agency Noon Social. He added that the title, Generalee Begum, was bestowed on her as both the British and the Mughals hated her. She offended the British by calling herself ‘Lady Ochterlony’ and upset the Mughals by awarding herself the title of ‘Qudsia Begum’, a designation previously reserved for the Emperor’s mother

Today, the mosque continues to be operational under the Delhi Waqf Board, but not many, even in Old Delhi, have heard of it or can navigate it. “Around 10-15 people probably come here every day for namaz, but it is not that popular,” says a local shopkeeper.

Also read:

Qudsia Bagh

Not far from Kashmere Gate’s Inter-State Bus Terminus sits a char-bagh-style garden complex, Qudsia Bagh, commissioned by Qudsia Begum or Udham Bai in the 18th century. She, too, was a courtesan before she married the 13th Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah ‘Rangila’, a great patron of the arts. An ace administrator, Qudisa Begum wielded great power in her husband’s court and was regent of India from 1748 to 1754.

Once a grand palace, what now remains of Qudsia Bagh is a 20-acre complex with a mosque and a few pavilions, once used for lodging by the royal family.

“The 1857 uprising and later the British siege of Delhi marked the final destruction of Mughal Delhi, Shahjahanabad, and its surrounding areas. Qudsia Bagh, near Kashmere Gate, was among the numerous structures which were dismantled by the British and left in ruins. Still, the scars of 1857 can be seen on its palace, of which only parts remain, and its private mosque, the Shahi Masjid, as well as other structures within the premises of the Bagh,” writes archivist Tanuja Bhakuni, who documents Delhi’s history in her blog, Zikr-E-Dilli.

The scarred remains of the bagh still offer a measure of peace and quiet to visitors.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)