New Delhi: Miniature paintings often conjure images of Mughal courts, mythological scenes, and meticulous detailing. But some modern artists have subverted this tradition. Manjit Bawa simplified and reimagined Hindu deities, showing Goddess Durga riding a panther instead of a tiger. Nilima Sheikh told stories of Kashmiri life, while Rajasthani miniaturist R Vijay and American photographer Waswo X Waswo tackled power dynamics through their collaborative work.

“You cannot be trapped by narratives,” said art historian Geeti Sen at the launch of her latest book, Alchemy: Contemporary Indian Painting and Miniature Traditions, at the India International Centre. The book examines how five artists—Abanindranath Tagore, Manjit Bawa, Waswo X Waswo, R Vijay, and Nilima Sheikh—have adapted and evolved India’s miniature painting traditions.

The event included an hour-long slideshow of miniature-inspired works by these artists, with Sen pointing out their remarkable features and current relevance. While showing Bawa’s Durga miniature and its dismantling of traditional conventions, she said he was “not just a painter, he was an activist; a complete saviour.”

In the dimly lit hall, about 70 art enthusiasts listened attentively. Many seemed to know Sen personally, adding an informal, familiar air to the evening.

In conversation with cultural historian Dr Giles Tillotson, Sen explored how contemporary artists have drawn from and reinvented the miniature tradition through their different perspectives, breaking away from rigid stylistic and historical frameworks.

One of the most thought-provoking works came from a collaboration between Waswo and Vijay, depicting the tension and intimacy between a Western photographer—Waswo himself—and a naked Indian subject.

“There is a current that separates them—you can feel it in this painting,” said Sen, as the artwork appeared on screen. “They’re completely different, but both are made small, as a miniaturist would, in scale with the landscape.”

Sen added a light-hearted comment directed at Waswo, who was in the audience.

“It’s absolutely extraordinary how the two of them are made in the same size. I know Waswo—Waswo is huge. Excuse me, Waswo,” she added, drawing laughter.

Also Read: The luminous miniature paintings of Mewar — a centuries-long tradition

Kashmir in miniature

While miniature painting is often seen as a relic of the past, Sen presented works by contemporary artist Nilima Sheikh to show that even if form stays the same, stories evolve.

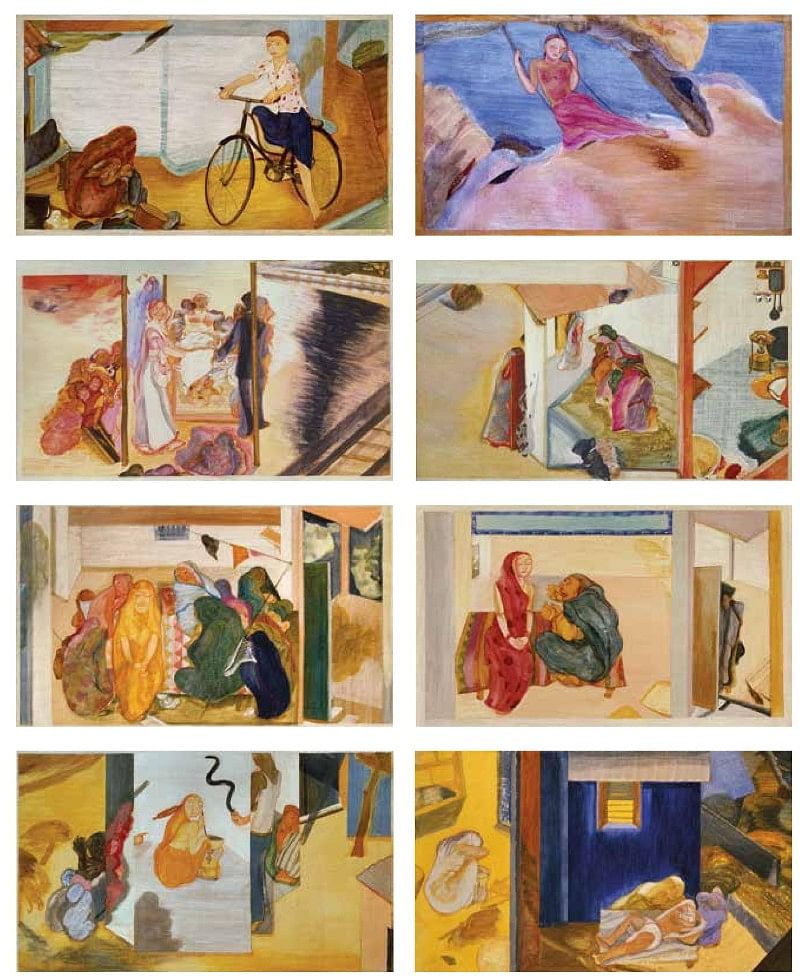

Sheikh’s miniatures zoom in closely on intimate, everyday moments from Kashmir, based on her personal and interpersonal experiences

Known for using traditional forms to explore modern themes of displacement, violence, and femininity, Sheikh chose not to illustrate ‘Kashmir’ as a grand narrative. Instead, through a series of paintings, she told the story of Champa, a young Kashmiri woman who was murdered for dowry by her husband’s family.

“(Champa) was not even 18 when she was married and died within a year of marriage,” Sen said. “In one painting, she’s shown in her innocence, riding a bicycle. In the next, she’s playing on a swing before her marriage.”

Traditionally, Indian miniatures were often created as illustrations for texts. Artists like the Mughal painter Sahib Din illustrated epics like Ramayana, while modernists like Raja Ravi Varma used the form to depict gods and religious texts for those who couldn’t read.

But Sheikh’s work diverges from this tradition, using miniatures to focus on quiet, human moments instead of myth or grandeur.

“Unlike most contemporary artists, [Nilima Sheikh] doesn’t like looking at herself as an illustrator,” Sen said.

Also Read: Abanindranath Tagore rejected European art. Promoted Hindu spirituality to convey ‘Indianness’

Reinvention and renewal

The 20th-century Bengali artist Abanindranath Tagore didn’t just bring nationalism into Indian art, but breathed new life into miniature painting.

Sen credited him with reviving the form through indigenous techniques and styles. His work often reflected Mughal influences, complete with elaborate borders. During the discussion, Sen presented his painting Abhisarika, depicting a woman stealthily going out into the night.

According to Sen, the Abhisarika is a popular Rajput representation of a heroine who, in a moment of transgression, goes out to seek her lover.

“She is shown running away from her home, often barefoot, and rather flustered, with her hair dishevelled, snakes in her way in the forest, amidst thunder, rain,” Said Sen. “And she braves her way through all this to find her lover.”

In the Q&A session, a man in the audience wearing a pahadi cap asked, “I was going through your beautiful book, and while it’s very nice, I noticed you’ve only included established names. What about new, contemporary, and emerging talents?”

To this, Sen offered a frank reply.

“I actually don’t know the answer to your question, but maybe it is time you write a book,” she said. “I am old fashioned, and I am biased, so I chose to write about those artists who would fulfil my ideas. And I don’t know young artists well enough to write about them.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

So Geeti Sen knows that Waswo is “big”. Wow!

Along expected lines though. After all, these are high society liberal progressive folks. They usually know how “big” everyone else in their social strata is.

Bengal used to be India’s intellectual vanguard against the onslaught of the West. It’s sad and disappointing to see how far it has fallen from it’s glory days. People like Geeti Sen represent the current state of Bengal.

Manjit Bawa’s depiction of Goddess Durga is not “bold and minimalistic”. It’s downright sleazy and offensive.

Also, his paintings come across as that of a child who has just recently learned how to draw. Nothing remarkable at all.

These people – Geeti Sen, Waswo, Rajiv, etc. – are part of a clique. It’s an elite society where everyone scratches everyone else’s back.