The Euromaidan revolt that ousted former Ukraine President Victor Yanukovych and the Donbas conflict resulted in a wide range of cinematic content in both Ukrainian and Russian from 2014 onwards. Some teleport you right there in Ukrainian war-torn territory, but if there’s one thing that’s certain, it’s this — cinema is now the entry-point to history for many, not textbooks that follow the diktats of a president banning words like ‘war’ and ‘invasion’ on paper.

“Look at him, he doesn’t look like a courtyard sweeper. An ordinary bum! Piss off…don’t take offence. I’m just getting into my role…more paint! Is this your first time? Gathered up some trainees..,” a middle-aged actress banters with a fellow actor and her makeup artist in an unspecified part of occupied eastern Ukraine as her group prepares to set up fake TV interviews over a bus explosion.

On first impression, the above dialogue from the 2018 film Donbass may appear to trivialise what has been a protracted and devastating war. But conflict, government upheaval, and uncertainty have been consistent realities for Ukrainians since the country’s founding, be it the Revolution on Granite, the Orange Revolution, Euromaidan, or the subsequent eight years of conflict in the Donbas region in the east.

Amateur and professional filmmakers alike have chosen to reflect these realities in their works over the years, especially after pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych’s ousting as president in early 2014.

The ongoing Russia-Ukraine war has had a spillover into the film industry with some Ukrainian filmmakers calling for a boycott of all Russian cinema, including producer Denis Ivanov’s works. In light of these developments, the diversity of perspectives and the stories represented in these works deserve the attention of audiences across the world.

Also read: Stephen King’s Putin takes on ‘comedian’ Zelenskyy & Russian bear runs into prickly porcupine

Bleak history, colourful celluloid

Due to such a troubled past and present, issues like ultra-nationalism, identity, self-determination, and preserving sovereignty have been at the front and centre in most analyses of Ukrainian politics and society.

Prominent filmmakers bringing these issues to the international stage include Valentyn Vasyanovych and Sergei Loznitsa, both of whom have offered fictionalised yet realistic depictions of war-torn Donbas since 2014.

While Vasyanovych’s sci-fi dystopian film Atlantis (2019) made a splash at the Venice Film Festival, Loznitsa has been prolific with documentaries and feature films. His dark comedy Donbass (2018) is particularly striking, winning the Un Certain Regard award at the Cannes Film Festival in the same year.

Set in the year 2025, one year after the supposed end of the war in Donbas, Atlantis masterfully uses extended wide shots and thermal cameras with little dialogue to capture the bleak lives of two former soldiers who go about their routines as if the war never ended. The male veterans don’t exactly have a lot of friends in the area, as they are blamed for contributing to the breakdown of the region. It adds to the bleak, desolate atmosphere that Vasyanovych goes for at the outset of the film.

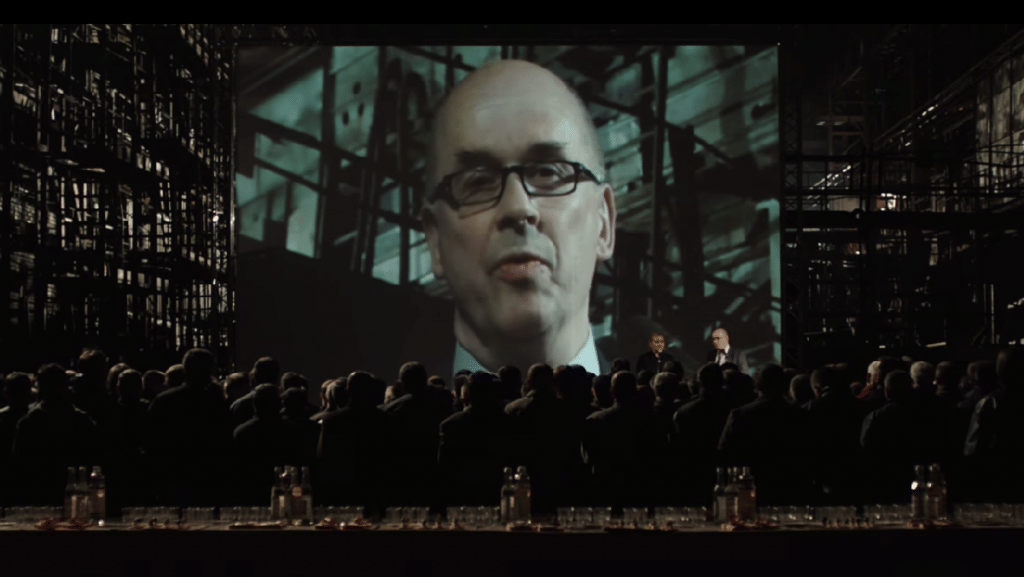

Donbass, however, takes a completely different approach as Loznitsa employs an intelligently and justifiably cynical style of comedy. Showcasing crisis actors, mud-slinging politicians, and activists across a series of seemingly disconnected vignettes, Loznitsa successfully portrays the farce and levity amongst the collapse of a functioning society, with lawlessness, corruption, and propaganda a common sight.

Alongside the satire and grim depiction of reality in these films, there appears consistent love for the Donbas region, its people, and what they have been through since 2014. For all the immense problems of eastern Ukraine that Atlantis and Donbass are unflinchingly honest about, the directors seem to view the region’s people as resourceful and resilient.

But thanks to the success of such directors, Ukrainian nationalism and the cinematic coverage of the conflict has often been seen as fairly male-centric.

Also read: Why’s Ukraine President Zelenskyy a winner? Watch TV comedy ‘Servant of the People’ for answer

Showing war at home

In this male dominant industry, Iryna Tsilyk’s 2020 film The Earth is Blue as an Orange stands out as a depiction of the impact of war and conflict on domestic spaces. Be it the Vietnam War or the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the moment of crisis and its representation is often validated by the participant’s narrative. That narrative is, by and large, hijacked by the perspectives of men or even women who fight the conflict with armour.

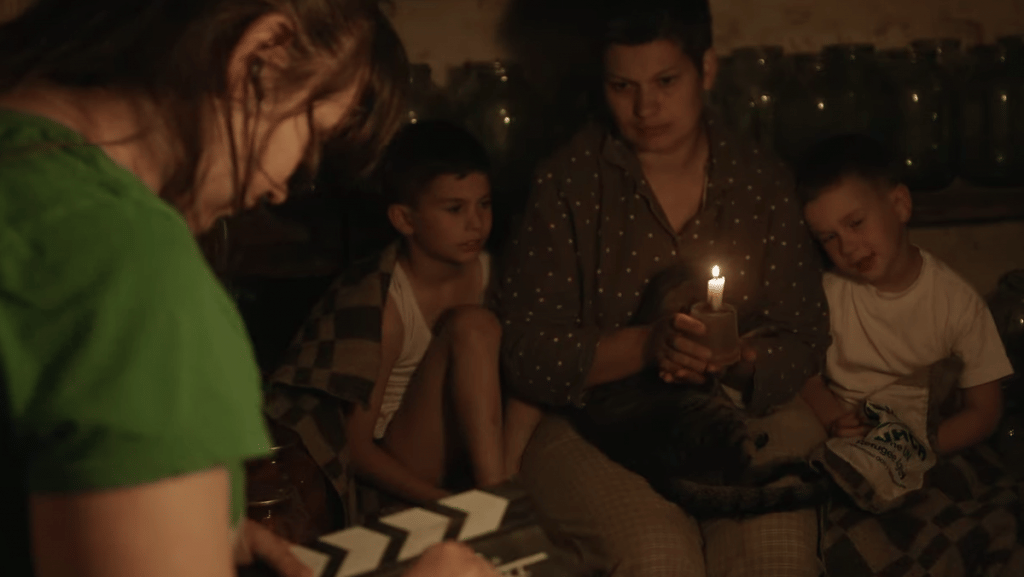

Tsilyk’s 74-minute-long documentary addresses this bias through the story of Hanna and her four children who live in the front-line war zone of Donbas. The family finds hope in the art of filming their lives — a passion that each member nurtures and feels ‘at home’ with. However, at the beginning of the film, their attempts to create a studio setup are cut short due to a bomb attack. The final product, a film recorded inside the house, is screened in front of their friends and relatives. It showcases a rebuilding process of Ukraine — of hope after the revolution.

Also read: Actor Sean Penn finds his next project in conflict-torn Ukraine, to shoot Russian invasion

Ringing bells at home in India

Netflix, too, released its offering on the Euromaidan revolution in 2015, titled Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom. A fairly straightforward documentary akin to those aired on contemporary international news channels, Winter on Fire captures the vibrancy of the protest, which was largely led by students but also included civilians from all walks of life.

Shot by Israeli-American director Evgeny Afineevsky, Winter on Fire and its raw footage, interspersed with interviews, seems familiar. Especially if one attended the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 in India that, akin to Euromaidan, saw protesters using music, dance, and poetry to raise their voices against the State.

“I am here to defend the future,” says a protester in the documentary. The sheer energy in Winter on Fire is contagious and would probably remind India of the farmers’ protest, especially the role that songs and music played throughout the struggle.

The documentary also looks at the power of social media to have a positive impact, as many protesters talk about how Facebook posts helped them mobilise and share stories about the protest with the people who were a part of it.

Also read: Russian ‘state media’ outlet removes trailer of film equating Kashmir & Palestine, cites threats

The Russian side of the coin

Constructions of Ukrainian nationalism and identity are wholly incomplete without looking at what the other side — the Russians — has said. Given the turbulent history of Ukraine’s sovereignty as well as the complex linguistic demographics within the country, it is essential to also analyse Russian cinema in the same breath.

Critically-acclaimed Russian cinema that gets recognition at global film festivals is often more inward-looking and domestic-centric where the content is critical of President Vladimir Putin and his government’s institutions. Andrey Zvyagintsev’s depiction of corruption and local politics in Leviathan (2014) is a notable example, which stirred controversy in Russia.

Other popular Russian-language films about the war in Ukraine, such as Opolchenochka (2019) and Krym Put na Rodinu (2015) are little more than just propaganda. But the niche documentary space has allowed for greater nuance, with Olya Schechter’s A Sniper’s War (2018) gaining attention at film festivals for portraying the Donbas conflict from the point of view of Deki, a Serbian sniper fighting for the Russian military.

Through Deki, Schechter gets inside the mind of a mercenary murderer and a foreign supporter of the pro-Russian separatists with grievances against the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for its involvement in the war in Bosnia in 1990. As such, Schechter addresses a question that few in media or the film industry in Ukraine or the West have bothered to answer.

Also read: This is how the Ukraine-Russia war can look like in coming days — and what can end it

Stop with the ‘colonial’ bias

Then there’s the acclaimed American director, Oliver Stone. Decades after winning awards for Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989), Stone only recently emerged as a strong supporter of the Russian government and its activities in Ukraine. The filmmaker had served in the Vietnam War and has been vocal about his criticism of US military interventions and foreign policy, which explain many of his pro-Russia stances. “A dirty story and in the aftermath, the West maintains the dominant narrative of “Russia in Crimea” — the true narrative is ‘USA in Ukraine’,” Stone tweeted in December 2014 several months after Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Although he has condemned Russia’s ongoing invasion, he previously put out documentaries like Ukraine on Fire (2016), Revealing Ukraine (2019) and The Putin Interviews (2017) that reflect a brazen attempt to speak for a region he has little understanding of. It shows a ‘coloniser’s bias’ — unabashedly speaking for a people one isn’t a part of.

The Putin Interviews, however, offers an exclusive insight given by a Western filmmaker into the Russian president’s life, ideologies, and politics. From childhood to the US-Russia relations, this documentary looks at everything in ways that few managed before.

Regardless of one’s position on the Russia-Ukraine war and the level of knowledge of the last 30 years history, it is essential to parse through these works — the fictional and the propaganda — in order to best understand how national identity and political biases, of both the locals and the outsiders, have shaped the cinematic and societal landscape of this conflict-affected border region today.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)