New Delhi: A work of fiction published 31 years ago, Lajja transcends time and moves from fiction to fact in documenting the condition of Hindus in Bangladesh today.

And though there was no Citizenship Amendment Act in India to provide refuge to Hindus fleeing the country when Taslima Nasrin’s novel came out, a new play based on it serves as an unspoken yet emphatic nod to the CAA.

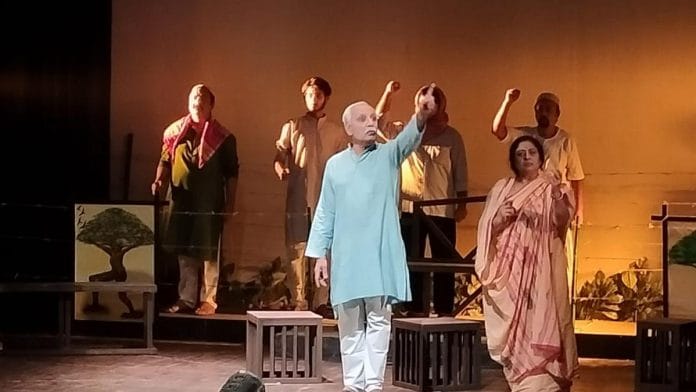

Adapted by the theatre group Nabapally Natya Sanstha, Lajja was staged at the Bipin Chandra Pal Auditorium in South Delhi on 17 November. The performance vividly demonstrated how Nasrin’s 1993 novel—still banned in Bangladesh—is just as as relevant today as it was 31 years ago.

Closely mirroring the book, the play tells the story of the fictional Dutta family as they face rising communal hatred and Islamist attacks against Hindus in Bangladesh after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in India in 1992. The themes of fear and betrayal resonate even now.

If the fall of the Babri Masjid were replaced with the fall of Sheikh Hasina, the events in the play would play out much the same.

Also Read: Jamaat wants Islamist Bangladesh. Is former ally BNP standing in the way?

Fiction, facts, fanaticism

Lajja is not just a story of one family but an indictment of a ‘secular’ nation’s fractured promises.

It does this by capturing the tension between Sudhamoy Dutta and his son Suranjan, as Hindus in Bangladesh are forced to pay the price for the demolition of Bari Masjid in India.

For Sudhamoy, Bangladesh is the homeland he’s held onto through the brutalities of Partition in 1947 and the upheavals following the 1971 war, when the “Khan army” stripped him of his lungi “to check his religion and then unleashed unspeakable violence”.

Suranjan, an atheist and a member of the local communist party, initially shares his father’s loyalty to the nation—until harsh reality sets in. Disillusioned with daily news of Hindu temples being attacked, men being killed, and women raped, Suranjan’s only hope is his love for Ratna—a Hindu woman—and the prospect of a life together. But that hope shatters when Ratna admits she once considered marrying a Muslim man to stay safe, and his own sister Maya is abducted by an Islamist gang from their home. Suranjan then spirals into rage and despair. He takes to the bottle, bays for revenge, and abuses a Muslim sex worker because of her religion.

Today, Bangladesh is going through a similar churn. The radicalisation of Bangladeshi society, attacks on Hindu homes and temples, and Jamaat-e-Islami’s growing influence have escalated since Sheikh Hasina was ousted as prime minister in August.

Bangladesh’s leading newspaper Prothom Alo has reported that between 5 and 20 August alone, at least 1,068 houses and businesses belonging to minorities were looted and vandalised. Hardly a day passes without news and videos of attacks on minorities posted on X—even as the interim government dismisses them as “propaganda from India” and sections of the Indian and Western media downplay them as stray incidents hijacked by the ‘Hindutva project’.

Here too, there are parallels with the Lajja— Suranjan’s communist friends fail to see the violence against Hindus as rooted in radical Islam, instead framing it a case of the powerful oppressing the powerless.

CAA only way out?

One of the most heartbreaking scenes in Lajja comes at the very end, in a dialogue between Sudhamoy and Suranjan after news comes of a body in the river that resembles Maya’s. Father and son, thus far estranged over their clash of ideals, finally agree on the grim future awaiting Hindus in Bangladesh as calls for Sharia law grow louder.

For anyone following the news from Bangladesh, this scene might seem all too familiar. In August this year, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami leaders held a meeting with top Qawmi scholars, with participants speaking emphatically about establishing an Islamic state under the leadership of Jamaat chief Dr Shafiqur Rahman.

“Come, father, let’s go to India,” Suranjan pleads in the play. Sudhamoy, who had once scorned the prospect of migration and looked down upon fellow Bangladeshi Hindus fleeing to safety in a foreign land, now concedes: “Yes, let us go to India.”

This is Lajja’s most politically charged line.

When the book was published, there was no CAA to provide refuge. But now, as conditions for Hindus in Bangladesh deteriorate, it’s hard not to see it as a solution.

Taslima Nasrin herself has described the CAA as “very good” and “generous”. But she has suggested one change—that the law should include an exception for Muslim “free-thinkers, feminists, and secularists” from India’s neighbouring countries.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)