According to the 2011 census, roughly 10.11 million children in India between the ages of five and 14 years are trapped in child labour. And given the job losses and looming recession, school closures and the migrants’ exodus from cities back to their homes in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown, that number is only set to increase.

In 2002, the International Labour Organization adopted 12 June as World Day Against Child Labour, an observance meant to highlight, and work towards reducing, the number of children engaged in labour at the cost of their health, safety and education. This year’s theme was focused on how a crisis, such as the novel coronavirus pandemic, could impact children, because, given the financial impact of a pandemic, many parents will feel compelled to take their children out of school and turn them into breadwinners.

Hindi cinema, given its reach and impact, is a powerful tool to tell such stories and make a change. And it hasn’t shied away from the subject of child labour. But too often, the stories told are inauthentic, given a glossy sheen and a purely commercial venture.

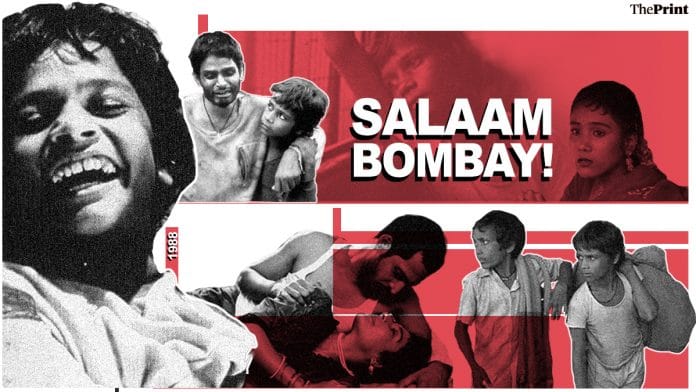

Mira Nair’s beautiful 1988 feature film debut, Salaam Bombay!, stands out as possibly one of the most haunting, ear-to-the-ground feature film on the subject of child labour. And the proceeds from the film were used to set up the Salaam Baalak Trust, an NGO that works for the welfare of street children. This weekend, there could be no better movie to rewatch.

Also read: Raj Kapoor’s Awara is all the more relevant in the context of India’s migrant crisis

When the street kids were the stars

Shafiq Syed plays Krishna, a young boy from a Karnataka slum who has, in a fit of rage, burnt his elder brother’s bicycle. His enraged mother drags him to the circus that has pitched up in the area and tells him that he is not to return until he earns the Rs 500 needed to pay for the bike’s repair.

One day, his boss sends him to go buy paan, and when he returns, he finds that the circus has moved away. With nowhere to work and the conviction that he cannot go home without the bike money, Krishna heads for the train station where he buys a ticket. He doesn’t even know where to go, and asks the ticket vendor, who advises him to go to Bombay.

Once in the big city, he manages to get a job as a runner for a tea vendor, delivering glasses of cutting chai to the locals in the slum where he sleeps on the street, no longer Krishna, but Chaipau, as the people around call him.

Chillum (Raghuvir Yadav), a drug peddler and addict who becomes a kind of mentor to Chaipau, works for Baba (Nana Patekar), a selfish, weak man and former pimp who promised his partner Rekha (Aneeta Kanwar) a life outside of prostitution once their child Manju (Hansa Vithal) was born. But that has not happened in years, and Rekha is forced to sometimes even take her beloved daughter along with her to client’s houses.

Meanwhile, the nearby brothel, run by a greedy madam (Shaukat Azmi), gets a new girl, whom an infatuated Chaipau calls Sola Saal (Chanda Sharma), and whose prized virginity is to be auctioned off to the highest bidder.

This debilitating world of drugs, prostitution and child labour and how Chaipau navigates it forms the story, but it is so much more than that.

There are some movies whose production is as interesting a story as the actual plot, and Salaam Bombay! is one of them. Because even though the cast includes well-known actors and even features cameos by Sanjna Kapoor and Irrfan (credited as Irfan Khan), the real stars are the street children.

Nair was clear that she wanted actual street kids to play the roles of the children, and that is, perhaps, one reason her film rings truer than many other efforts. Theatre veteran Barry John workshopped extensively with the children, who were even shown films such as Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Luis Bunuel’s Los Olvidados.

Written by Nair and Sooni Taraporevala, the film stands out not only for its gritty, heartbreaking performances and tight screenplay (courtesy Taraporevala), but also for its musical score (L. Subramaniam) and sensitive cinematography by Sandi Sissel. The film won a slew of awards, including two National Awards, two at Cannes and one from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and was nominated for a Golden Globe, a BAFTA and an Academy Award.

But its real triumph is equally its heartbreaking truth — the fact that more than 30 years later, it is still all too relevant.

Also read: Sadma is an achingly beautiful story about a love that defies labels