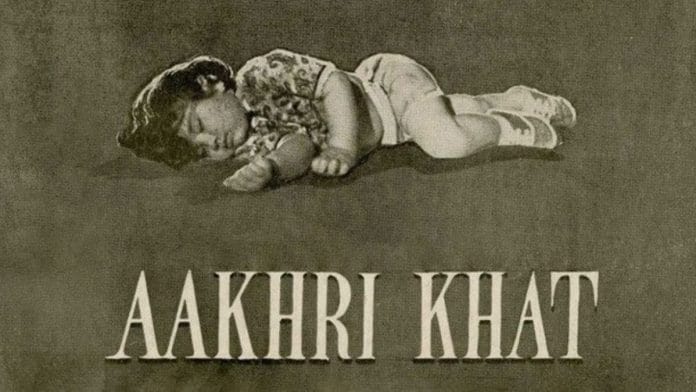

Rajesh Khanna, one of Bollywood’s biggest heartthrobs, was eclipsed by a 15-month-old toddler when he made his debut in Chetan Anand’s low-budget Aakhri Khat.

The film didn’t do well, though it was India’s first official entry to the Academy Awards. That said, it’s worth revisiting this 1966 movie even though the plot hinged on the tired trope of a mother’s death and the fate of her baby boy. The toddler stole the show. Aakhri Khat is a story of loss, longing, and fate. It is quietly poetic and deeply emotional.

Govind (Rajesh Khanna), a young sculptor, falls in love with Lajjo (Indrani Mukherjee), a village girl. They marry, Govind leaves for the city, and promises to call her back. However, circumstances change. Lajjo, who is now a mother, writes one final letter to Govind before her death, asking him to take care of their child.

What follows is an emotionally charged journey of a child lost in the streets of Mumbai, while his father desperately searches for him. On paper, it may sound like a tragic melodrama—but Anand transforms this into a powerful cinematic meditation on human vulnerability.

In 2007, Anand’s son Ketan, during a screening of his documentary, called the film a masterpiece. “… My father started with a bare outline of a script and a 15-month-old infant whom he let loose in the city, following him with his camera,” he said.

Bustling streets of Bombay

Aakhri Khat marked India’s early attempts at neo-realism. This shines through in the cinematography as the camera follows the boy (Master Bunty) who crawls, toddles, and wobbles through a chaotic, indifferent city. The use of natural light, the handheld camera work, and ambient sound to heighten the tension and the realism was impressive, given that it was shot in the 1960s.

One unforgettable scene shows the child scrambling through the food thrown on the street. In another, he is asleep on a pavement, while around him, the world blurs into motion, indifferent to his helplessness.

The child was not acting—he was simply living. And therein lies the genius of Anand’s vision. He captured those unguarded, organic moments.

Several scenes in Aakhri Khat linger long after the credits roll. Lajjo’s last letter to Govind is one such moment. The camera pans over her frail body as she lies next to her child. Indrani Mukherjee’s voice-over echoes hauntingly.

“Maine tumhare bina jeena seekh liya, par us bachhe ko kaun sikhayega?” (I’ve learned to live without you, but who will teach our child?)

In another scene, Anand heightens the tension when the camera follows the child onto the train tracks. He walks on his tiny feet, stumbles, and picks himself up again. The scene when a train barrels down the same tracks where the child is now sleeping is nail-biting and emotional. For a few agonising seconds, all you hear is the roar of metal on rails—until the baby’s wail pierces through.

The plot builds to the climactic scene where Govind hasn’t slept for three days. According to Gautam Chintamani, the author of Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna, Anand didn’t let Khanna sleep for three nights before the shoot. He would call him in the middle of the night.

“By the time Khanna arrived on the set to shoot the pivotal scene, he was a wreck,” he wrote in a 2018 article.

Also read: Hamraaz was Bollywood’s Shakespearean tragedy. Sunil Dutt, its Othello

A debut to remember

Khanna may have gone on to become a romantic hero, but his debut as a frantic father searching for his son shows a seldom-seen side to the actor. He was not even on Anand’s radar, according to Chintamani. In fact, Rajesh Khanna’s debut was supposed to be GP Sippy’s Raaz (1967). A chance meeting between the two men changed that.

“Anand knew that he had found his Govind,” wrote Chintamani. Khanna plumbed the depths of despair, vulnerability, desperation, and guilt—early proof of his commitment to his craft.

His debut did not rely on dramatic monologues or over-the-top emotional confrontations. He captured the longing of a father and a guilt-ridden lover just perfectly.

In the final scene, a weary and broken Govind sits beside Lajjo’s sculpture, lost in silence—until he notices a small child playing nearby. The moment the child looks at the sculpture and softly says “mumma,” Govind’s eyes fill with a flicker of hope.

Tears—of both solace and sorrow—stream down his face as he lets his body fall back in relief.

Fatherhood, urban indifference, and loss

Aakhri Khat is much more than a lost-and-found drama.

Without calling it out, the film shows what urban alienation looks like—how a city can swallow a soul without anyone noticing.

It also speaks deeply to the theme of fatherhood. In most 60s films, paternal love was authoritarian or peripheral.

But here, Govind’s journey is about rediscovery—not just of his son, but of his own emotional core. The music adds another layer to the story.

Mohammed Zahur Khayyam’s music is as poetic as the visuals.

The standout track, Mere Chand Mere Nanhe, sung by Lata Mangeshkar, is heartbreaking as it gives voice to the emotions of the mother’s spirit helplessly watching her son sleep on the steps of a church.

Another gem is Rut Jawan Jawan, which also marked a personal milestone for singer Bhupinder Singh. It was his first solo, where he debuted as a nightclub singer. The catchy song offers a momentary breather to the heavy emotions of the film.

A forgotten gem

Unfortunately, Aakhri Khat is overshadowed by Khanna’s more popular hits like Aradhana, Do Raaste, Kati Patang, Anand, Bawarchi and more.

Anand, too, deserves credit for not only making a film that defied many conventions but also for daring to let a toddler take centre stage.

Aakhri Khat isn’t just another film of the 1960s. It’s an emotional experience. Sometimes, the quietest stories leave the loudest echoes.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)