New Delhi: In the uncertain space between the tenacity of Sumit Verma and the dogged resilience of a pragmatic Qamar Sayeed, the fate of a beloved book market hangs in the balance.

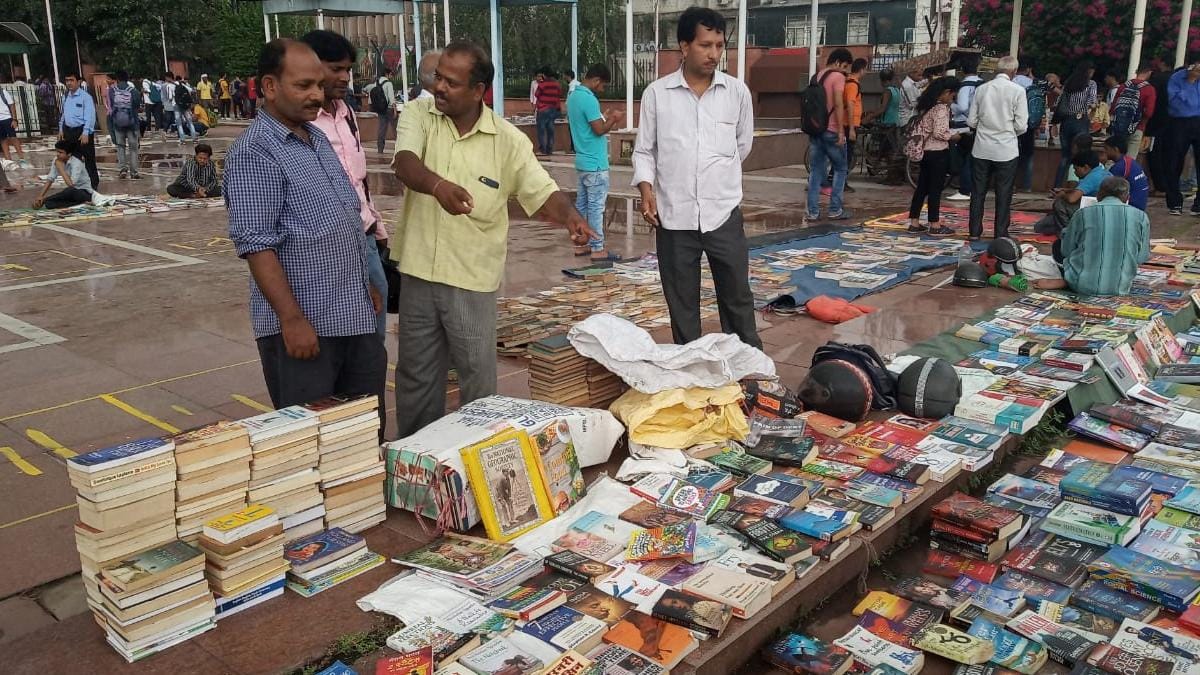

Nearly two months ago, when the Delhi High Court directed the North Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) to shut down the Sunday bazaar at Netaji Subhash Marg (Daryaganj) — declaring it a no hawking zone — an association of book vendors rallied behind a common cause. Bound by livelihood and loyalty to an over 50-year-old tradition, the Daryaganj Patri Sunday Book Bazaar Welfare Association and its 276 members marked the first Sunday that they were prohibited from setting up shop as a dark day in Delhi’s history.

But now, as the bazaar finds a new home in Mahila Haat, the united front of the book vendors’ association has split into two opposing camps — those cooperating and welcoming the relocation and those who want to continue to fight for what they view as their right over Daryaganj.

Internal struggle

In the microcosm of the seemingly innocuous book vendors’ association, a political unfurling is ensuing. The final agreement between the association and municipal authorities to move the Daryaganj market to Mahila Haat was taken on 12 September, “nearly two weeks after the president and vice president resigned”, says Sumit Verma, a book vendor in his mid-30s who is leading the internal dissent.

“All negotiations with the municipal corporation were supposed to halt until a new committee was formed, but despite that, the former council members sidestepped the process and met with the district commissioner. We were told, without discussion, that here is your two-year-lease. In place of our 50-year-old market, all we’re getting is betrayal,” Verma rails.

Former association president Qamar Sayeed is 58 and fleetingly compares himself to Mahatma Gandhi over the phone. He is riled up, evidently displeased at the accusations of wielding power without official mandate.

“Yes the elected council dissolved on 1 September,” he admits. “But in the intervening gap between that and fresh elections, the previous position holder must represent the members. I haven’t committed any crime,” he asserts.

“They’ve arbitrarily picked their own pradhan, and deputy chairman, but if the members didn’t trust me to speak on their behalf, then I wouldn’t have been in charge for 35 years.”

Sayeed ruminates on a sense of legacy, talking of days spent “sweating in the dust and dirt of the Daryaganj footpath to reach where we are today”. Rather than Verma’s sense of justice, Sayeed appeals to the older guard’s practicality.

“I can present my MCD documents from a time when Sumit Verma wasn’t even born — if the court is removing us from an overcrowded and traffic-laden area and giving us a better location, then it makes no sense to protest it for the sake of protesting,” says Sayeed.

In his acerbic view, “Verma is on his way to be a politician. A few more speeches, an arrest here and there, and he’ll have achieved a sense of duty”.

For Sayeed, as well as his right-hand man and former vice president Ashrafilal, “we care about earning a living and providing for our families”.

“It’s been two months and no agreement was reached with the NDMC. They showed us four places, which the association rejected on a vote. You have to understand, for many poor vendors, this weekly market was the only source of their livelihood — they have children to feed and send to school,” Ashrafilal tells ThePrint.

A divided Sunday

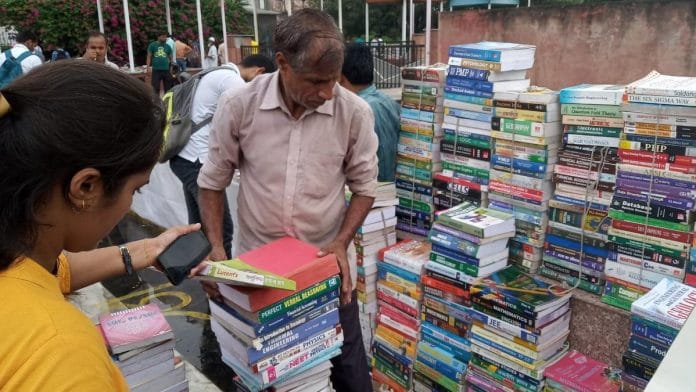

On Sunday, approximately 125 book vendors reached Mahila Haat at 7am to set up a display of their books within 6×4 feet of designated stall space each. Despite the first day at a new location, the bazaar witnessed a relatively good turnout, with the likes of Ramakrishna Chaudhary coming all the way from Gurugram to buy his daughter books.

“We came to know from the newspapers that the market is moving to a new place,” he told ThePrint, expressing relief and excitement at the prospect of continuing this tradition for his children.

For Sayeed, as well as other vendors who support him, Mahila Haat is a superior location to Daryaganj — “It’s clean, next to a park, there are toilets, and the NDMC is planning to create eating and sitting areas also.

“Members don’t mind paying the Rs 150-200 of rent on that one Sunday, because gradually people will start coming here and once again, the market will start running well.”

Hours later, in Daryaganj, the other half of the same association was staging a protest at the original site, supported by National Hawker Federation (NHF). Mohit Valecha, all India working president, NHF, told ThePrint, “The Municipal Corporation of Delhi is not following the 2014 vendor law.

“They have no right to remove these shopkeepers. We demand that once again these booksellers should be allowed to set up shop at their old place.”

Vendors held up posters reminding those passing by that affordable books were an integral ingredient of the Narendra Modi government’s ‘Beti Bachao Beti Padhao’ campaign — a line of argument echoed by Sayeed only a few weeks ago. Now, as the former president sits on the other side of the fence, and younger members like Verma plan to take the fight to court, it remains to be seen whether the bazaar will survive this level of in-fighting.

“We just can’t have two separate Sunday book bazaars — the customers will split. They will have to lose their court case for things to be resolved. And you watch, they will,” Sayeed says.

Both parties now await 25 September, the date of their next hearing before the high court.

With inputs from Krishan Murari.

Also read: What the girl in the pink burkha taught me about life and loss in Old Delhi