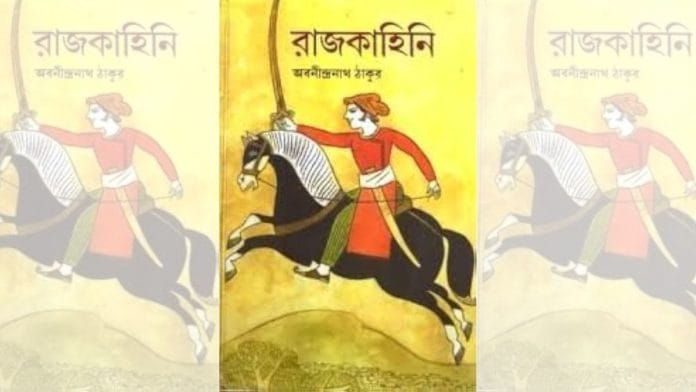

When Abanindranath Tagore wrote Raj Kahini—Bengali short stories on Rajput valour—in 1909, he wanted a glorious Hindu past to shape a turbulent present. Now translated into English by Sandipan Deb, these ageless stories bring into focus old fault lines in new India.

“It is not history,” Deb who has translated and adapted Raj Kahini into his new book Suryavamshi: The Sun Kings of Rajasthan told ThePrint. “But it gives you a sense of an era when Rajputs took on the invading Mughal armies. Like the way Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children tells you about the period of India’s transition from British rule to Partition and Independence.”

For Deb, the stories of Abanindranath needed to be translated for a wider audience and a new India that needs to remain connected to its roots. “The legend of King Arthur and his round table has travelled down the ages and remained relevant. So should Aban Thakur’s reimagining of the stories of brave Rajputs who defended their kingdoms with pride and honour, which he wrote during the first wave of India’s struggle for independence,” he said.

Rabindranath Tagore’s talented painter-writer nephew, Abanindranath, wanted to paint with his words and dream two impossible dreams. First, he hoped that a magnificent Hindu history would influence and stabilise his chaotic present. His Raj Kahini infused Swadeshi values in children and young adults.

Aban Thakur, as he was fondly called in Bengal, was also trying to keep caste aside and stitch a greater Hindu alliance against British rule after the Partition of Bengal was announced in 1905.

Both dreams are hotly debated political talking points today, even though India has been free from British rule for 76 years.

In 1905, Abanindranath drew the now-iconic Bharat Mata as a saffron-clad Sadhvi. As part of a larger nationalist project, he wanted Bengali children to grow up knowing about Bharat’s glorious history. The stories where the brave Rajput took on the mighty Mughal, often with support from courageous Bhil.

Also read: Bengali cinema finally moves on from Bakshi, Feluda. A new accidental detective is in town

Race memory married to history

Ironically, the tales Abanindranath told Bengali children to imbibe in them pride for the country were based on a book by a British officer. The short stories in Raj Kahini were inspired by East India Company officer, amateur anthropologist and historian Lieutenant Colonel James Tod’s book The Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan.

In the introduction to Suryavamshi, Deb writes that Tod’s account of Rajasthan’s history and demographics was “based on folklore, the race memory of the people of the land and his own diligent research”. But while Tod’s book, according to Deb, was a boring tome, Abanindranath’s language and imagination transformed the tales of love and sacrifice, jealousy and courage into “stunning word paintings”. Abanindranath, according to Deb, wrote itihasa, which marries history with mythology and race memory to tell tales of glorious dynasties.

The first story in Deb’s book is of Shiladitya, the boon-child of Suryadev, the Sun god, born to a Brahmin priestess. Riding a chariot drawn by seven horses and armed with the indestructible Adiyashila, or the sun-stone, Shiladitya raised armies and conquered faraway lands. However, he was betrayed by his most trusted minister, who desecrated the waters of a holy lake with the blood of a cow. Although Shiladitya was ultimately killed by a poisoned arrow by a “barbarian enemy,” the glory of the Sun Dynasty, or the Suryavamshis, that he founded was just beginning.

In Abanindranath’s stories and Deb’s retelling, treachery and betrayal, closely linked with pride and honour, become obstacles to the dream of a greater Hindu alliance.

The final pages of Suryavamshi recount how the brave Rana Sanga or Sangram Singh was poisoned to death by his own noblemen while preparing for the next great battle, despite losing an eye, an arm, and a leg. This is not mythology but recorded history. In the Afterword, Deb writes: “In 1527, he (Rana Sanga) would be defeated by the invading Babur on the fields of Khanwa. Sanga was the most powerful king that Babur had to fight in Bharat.”

Another historical figure surrounded by myths and featured in Suryavamshi is Padmini, the princess of the island kingdom of Sinhala. Her story, which includes her marriage to Bhim Singh, the uncle of Rana Lakshman Singh of Chittor, and the unholy obsession of Pathan Badshah Alauddin, the ruler of Dilli, is the stuff of legends and cinema. Padmini is portrayed not just as a sacrificial queen who jumped onto a funeral pyre to protect the Rajput honour, but as a smart strategist who hoodwinks a powerful emperor and frees her husband from prison.

“When Raj Kahini first came out, very few Bengalis had been to Rajasthan. In fact, Abanindranath Tagore himself may never have set foot there. But his stories have transported both Bengali children and adults to a distant land for generations,” Deb said.

The best kind of children’s literature, he said, is the one that adults can also enjoy. And Raj Kahini is exactly that.

Rajputs and Bhils

Whether in paintings or writings, Abanindranath Tagore wanted art to promote Swadeshi causes. Writer and economist Sanjeev Sanyal said that Abanindranath’s work brought alive an era of resistance to foreign occupation. “It bolstered a sense among young Indians, particularly Bengalis, that they were inheritors of a heroic spirit that had defended our civilisation against all odds,” he said. Sanyal’s latest book Revolutionaries is about India’s armed struggle against British rule.

“Deb’s translations bring the same spirit alive for today’s generation,” he added.

If the Muslim invader and the defending Rajput form a simple binary in his stories, the proud Rajput and the simple-hearted Bhil form a complex dynamic. Although fate causes Rajput prince Goha to grow up among the Bhils and eventually become their king, relations between these two warrior clans are not always cordial, despite their shared struggle against the Muslim invader.

“After Goha passed away, over the years and decades, the anger the Bhils felt toward the Rajputs kept building quietly, little by little. Then, one day, it burst into a blaze that engulfed the forests and the mountains,” Deb writes in the chapter Bappaditya.

Even though he wanted to stitch a greater Hindu resistance against the invader and liberally used mythology and magic realism in his stories, Abanindranath was aware of the caste tensions that threatened such an alliance.

For Sohini Ghosh, associate professor of Bengali literature at Vidyasagar College, Calcutta University, Abanindranath’s Raj Kahini are well-crafted stories of Hindu nationalism that should be handled with care in modern retellings.

“Raj Kahini is not history but there is high literary value in his stories as Aban Thakur could paint with words. But there is no doubt these were early instances of Hindu nationalism in literature. We should be careful in treating the stories only as literary masterpieces today and not for political ends,” she said.

The tribal community of Rajasthan has recently raised the demand for a separate state called ‘Bhil Pradesh’. They want to combine 49 districts of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. They also want to include 12 out of 33 districts of Rajasthan in the new state. The state government has rejected the demand.

This week, Parliament saw heated debates between MPs from the ruling alliance and the Opposition over the caste census. Much like in Abanindranath’s stories, dreams of a greater Hindu alliance are often dashed by existing fault lines, raising questions about the very need for it in a changed world. Sandipan Deb’s masterful retelling should remind us how certain things remain unchanged for centuries even as we marvel at Abanindranath’s imagination and ambitious dreams.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)