Mass hysteria breaks out in India every few years and is increasingly being fuelled by paranoia about the internet.

To the world, Manish Sarki was the perfect all-rounder.

A strapping boy of 18, Sarki worked hard in school during the day and sent fielders scurrying after his shots at the neighbourhood cricket ground in the evenings. He would never get home later than dinner time even when his friends were out chatting, his mother Chandra Maya remembers, and his closest friends joked about how he would blush talking to girls.

Everyone in the village of St Mary’s Hill knew Sarki would grow up to be a policeman or join the army. Maybe because he was so well-behaved, no one noticed when he went quiet. They only noticed on the night of August 20 when he didn’t come back home.

The village gathered around the Sarki house around 9pm. A chill was enveloping the small mountain village on the outskirts of Darjeeling in northern Bengal, but a small group of men and women trekked to the local police station a couple of kilometers away. Boys go missing all the time, they were told.

Undeterred, the villagers split into smaller search parties and fanned out into the jungles, determined to find Sarki. Their hopes were dashed around 1.30am when a search team stumbled on Sarki’s body hanging from the ceiling of an empty pig warehouse on top of a hill.

Below, in spray paint, were the words “half blood prince was here” in what everyone recognised was Sarki’s handwriting. On the wall behind was drawn a hangman with two victims, an older boy, and more chillingly, a younger one. Every wall of the building had been scribbled on – the words “illuminati”, “last king”, “savage”, “doped up” and the number “666” appearing repeatedly.

In the light of day, some of the graffiti might have appeared benign – after all, some the walls displayed banalities like “be the change you want to see” or “the thing you fear the most is fear itself”. But in the eerie quiet of a cold mountain night, the villagers were convinced Sarki’s death was the doing of the satan. “I was heartbroken for my son but also scared out of my wits. We were all scared about who the younger boy could be,” said Chandra Maya.

By the time police arrived two hours later, a mist of rumours had cloaked the village. Wasn’t Sarki always on his phone for the past few weeks? And, wouldn’t he go out to the graveyard, barely a kilometer away, every night with his phone? “I think he was going crazy. That’s when I heard about the game,” added Chandra Maya.

By sunrise, everyone had heard of the game: a shadowy application called the Momo Challenge that had apparently killed Sarki. Several explanations were offered. “For the past few days, he was very sad and distracted. He would be lost in his phone. He never said anything to me, later I found out that he was playing the Momo game,” said Sarki’s friend Deekchen.

But how did he find out? Villagers say the local police first told them of the game, but the police deny ever saying anything. “In fact, we have not been able to confirm any role of any Momo Challenge game. We never told the locals about the game. Maybe the graffiti made them think that,” said Hare Krishna Pai, additional superintendent of police.

‘Hi, I am Momo. Let us play a game’

The next day, a second death, that of 26-year-old Aditi Goyal in Kurseong town, was also attributed to the Momo Challenge, turning the creeping fear into full-blown panic. By then, local politicians had put out statements about the supposedly lethal game, and everyone in the hills was talking about it.

“The whole area was in trauma and everyone was scared of their phones. We found young boys from Class 7 had started playing it. We started spreading awareness and seized phones from those who seemed vulnerable. Someone even sent a message to my daughter,” said Raju Gurung, a local from Kurseong.

Hindustan Times spoke to at least 20 people in the area and everyone claimed to know a relative, friend or neighbour who had had a close shave with the game. But everyone had a different notion.

Some described the game, which supposedly sets self-harm challenges that finally end in suicide, as an app, some as a Whatsapp message. Some said they received texts, some described a phone number. Indeed, beyond the ubiquitous image of the oblong faced, bulbous eyed doll that has come to signify the game, every detail was foggy. “Sometimes people are faking names and photos and sending messages ‘Hi, I am momo. Let us play a game.’ The fear of the game has hypnotised us,” said Junita Rana, a schoolteacher in Kurseong.

An epidemic of fear

It began with the braids. In June last year, a girl in Rajasthan claimed someone chopped off her braid while she was asleep. Dozens of women across Rajasthan followed up with similar claims. Over the following months, the pattern spread across north India like an epidemic: Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab, Delhi. By November, over 200 cases of braid chopping had been reported in Kashmir where the trend took its most vicious turn. Many women claimed to have seen Godmen, witches or cats before losing their consciousness. After finding their braids gone, many complained of aches and pains for days after. The police couldn’t really find any culprits, so the people took the matter in their hands. In August, a poor woman was killed by a mob in Agra on the suspicion of chopping braids. In October, an old man in Anantnag was killed for the same reason.

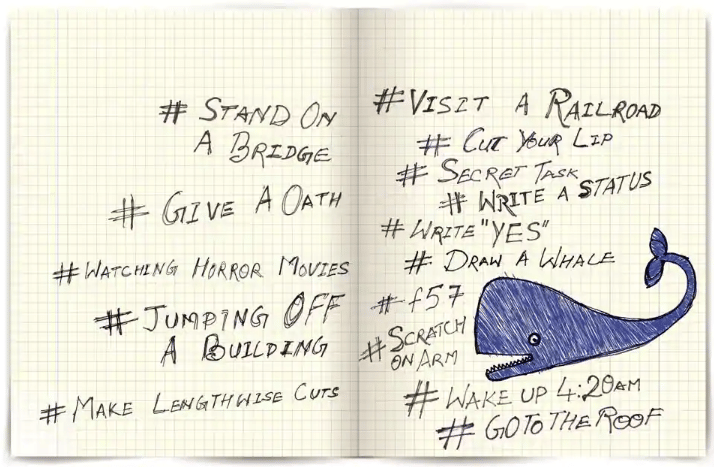

Then there was the Blue Whale. In July, a schoolboy’s suicide stoked the hysteria around the web-based game created by a Russian tech geek targeting teengers. The 50 challenges begin differently – from shutting yourself in or watching a horror film – proceed incrementally, and end the same way: suicide. Through 2017, more than 150 cases of young suicides across India – West Bengal, Delhi, Indore, Solapur, Dehradun – were blamed on the Blue Whale, often with no more proof that the young person was obsessed with smartphone and videogames. Every case was rife was contradictions and yet, websites were blocked, advisories issued, and in some cases, smartphones banned in schools.

Face-rippers and vampires

Experts say that underneath the web-fuelled hysteria, something more sinister is going on with the mental health of young people. Samir Parikh, director of the Department of Mental Health and Behavioural Sciences at Fortis Healthcare, insisted that we cannot dismiss these phenomena, but the focus should be on greater media literacy, on making children understand what is right and wrong content, and on teaching people to seek help if they are feeling vulnerable.

“Is there a component of hysteria in all this? Of course, there are lots of stories in the media and they have an impact. But we cannot deny the fact that there are pressures and problems that young people go through silently. If help and access is not given, they can be misused,” he added.

Parikh is clear that any approach that aims at shutting down access to the internet is wrong, mainly because it is impossible. “We need to understand that be it Blue Whale or Momo, if you are vulnerable, you might be pulled towards it. So you give people skills and teach people to not bottle it up, tell parents, block or involve authorities.”

India has had a long history of public panic. From a half-man half-monkey roaming the streets in Delhi, sometimes wearing a helmet, to the Munhnochwa (face ripper) of Mirzapur, claimed to be a flying object emitting beams of green or red light, sending shock waves through anyone who came in its contact, and leaving them with bites and scratches on their faces, to the Rathakaatteri (vampire) of Gundalpatti who allegedly sucked the blood of the village cattle, a new panic seizes the public imagination every few years. Many of these have been analysed as incidents of mass hysteria. The patterns have been revealing. Women are more likely to end up as victims than men, children turn to be more vulnerable than adults. The trends pick up in regions or communities marked by oppression of women, economic uncertainty or social anxiety.

Yet, questions remain about why a particular fear grips a set of people at a given time. Did every woman who complained of braid chopping do it herself? Was every alleged case of Blue Whale suicide made up by the parents or the police to evade responsibility? What do the women whose braids were chopped say now? And, did a year of fear and panic leave us any wiser?

Losing braids, earning rest

In Kanganhedi, a village of 700 houses on the Delhi-Haryana border, Munesh Devi’s hair has grown back just enough to tie it in a ponytail. A lot more has changed in her life since last year besides her hairstyle. “I can no longer work in our field. I hardly leave the house, except being taken to the doctor by my son every two weeks. Any exertion leaves me tired. Even going to funerals gets up my blood pressure. I lie in bed almost all day. Daughters-in-law press my feet.They also bring me rotis to eat in bed,” said Devi, sitting on a double bed in the living room. Its doors remain shut and its light dimmed to prevent Devi’s recurring headache.

They began in July 2017, immediately after she found her braid chopped at the neck. It was there when she finished feeding the cows in the family’s farm, she said, but gone when she got back home and slipped back her pallu. “Must have gone missing while I was travelling home on the back of my son’s motorcycle,” she added. She remembers fainting after the realisation struck. She continues to feel giddy. “My head spins. My whole body aches. My feet go numb. My teeth hurt.” She doesn’t know what ails her; neither does her doctor. He prescribes her pills for each of her symptoms. She shows off the stash to people asking her how she has been doing since “the incident.”

Munesh Devi’s was one of three braids found missing in the area in the course of one eventful day. The other two women don’t know, either, who chopped their braids or why they continue to suffer. Sri Devi said she lost her braid while sitting on a couch in the courtyard of her house. One moment it was hanging down her waist, the next moment it was lying on the floor. She had heard of the braid-chopping phenomenon only hours before. “My uncle, who was visiting us from Pataudi, had told me about a video he had seen on Facebook. I said, ‘Mama, please don’t say such things.’” Her son had called 100 after she fainted at the sight of her severed braid. “The police are yet to tell us if they found anything,” she said.

Devi also visited a psychiatrist in Dwarka along with her son, at the urging of the police. “He asked my son some questions. Gave us no answers,” she said. Her braid was taken away by a forensics team sent in by the police for further investigations. “We haven’t heard from them.” Perturbed by three incidents in a week, people in the village even consulted a tantrik (mystic). “He spoke about the presence of a mysterious cat in the village. But no such cat or dog has been found,” she said.

For many women, the disappearance of braids has been transformative. It has allowed them rightful rest after a lifetime’s slog at home and farm, won them the nurturing attention of their families, and given them the chance to talk about themselves for the first time. The third “victim” in Kangnahedi, Ombati, a daily-wage labourer who found her braid gone while working around the house, is still waiting for her life to change, however. “No government compensation, no one has even come to offer me a glass of juice,” she said, lying on a cot and complaining of a headache.

“We sent a team to that village for a couple of hours after a request from the concerned division of the Delhi police, but we haven’t received any formal communication from the top brass,” explained Nimesh Desai, director of the Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences, which had investigated the phenomenon of Delhi’s Monkey-man in 2001. “From the preliminary impressions of our team, in all probability, the incidents in Kanganhedi fit into the pattern of mass hysteria, which tends to subside on its own.”

Masked men or maids?

In Kashmir, the last region to be swept up in the storm, over 100 FIRs were registered over six months. Many women alleged masked men entered their homes when they were alone, sprinkled sedatives in the air, and chopped their braids while they lay unconscious. Separatist leaders accused the Indian government, and armed militants suspected the evil hand of intelligence agencies. As locals flooded the streets in protest, shutting down shops and schools, the police resorted to extreme measures, from announcing an award of Rs 6 lakh for information to unleashing riot-control tactics to disperse the crowds. Several vigilante groups armed with lathis and axes emerged to patrol the streets at night. A 70-year-old man in Anantnag died after being hit by a brick by a group of people who suspected him to be a braid chopper.

But now, police say the paranoia and panic was fuelled by nothing substantive.

“Almost all the cases turned out to be without any substance. There were a few cases where the women had cut their hair themselves. In one case, a maid had cut the hair of a girl,” said additional director general of police (law and order), Muneer Khan. In Kulgam, where 21 cases had been registered, the state government had formed a special investigation team(SIT). Additional Superintendent of Police (ASP), Kulgam, Aijaz Ahmad, who was part of the SIT, said that most of the cases have been closed because the allegations had no factual basis.

“In some of the cases, the culprits remain untraced, while maximum cases turned out to be of hysteria,” Ahmad said. He said the lack of a single eyewitness in all of the cases was particularly baffling.

Across the valley, the police arrested between 70 and 80 people, including members of vigilante groups, for “raising false alarm about braid chopping and creating disturbances”.

“We felt that this [braid chopping] was being done by agencies. It was a matter of honour of our women. Everybody wanted this should end. Stone pelting was the only option with us. Surprisingly it did end abruptly after that,” said a villager from north Kashmir who requested anonymity. Some of them are still visiting the courts for hearings.

Blue whales and phone bans

It was around 5pm on July 29 last year when Manpreet Singh Sahani climbed on the ledge of his fifth-floor apartment. As he teetered on the edge, neighbours and witnesses on the street below called out to him but could only watch helplessly as he jumped. Initial investigations by local police and testimonies of his friends exposed talk of the Blue Whale Challenge. Several of them took to social media to blame the game and link it to Sahani’s death.

In 24 hours, reports of the supposedly lethal game had inundated media, and reports of copycat cases were streaming in from all parts of India, ratcheting up paranoia about mobile phone and internet use among teenagers and their parents. Over the next two months, more than 150 deaths or injuries across the country were alleged to be linked to the game.

But while police initially suspected the boy was an avid gamer and could have been influenced by the Blue Whale Challenge, detailed investigation indicated more offline triggers.

“The boy was in love with a girl who had left him for some other boy. We had gone through his email accounts and mobile phone and found a draft on the phone which clarified his intention to commit suicide,” said Navin Reddy, deputy commissioner of police Zone 10.

This might not be an isolated phenomenon. Earlier this year, Union minister of state for home Hansraj Ahir told Lok Sabha that a committee formed under the chairmanship of the director general of the Computer Emergency Response Team-India (CERT-In) couldn’t establish the involvement of the Blue Whale Challenge in any case.

“The committee analysed the internet activities, device activities, call records and other social media activity, other forensic evidences and also interacted with rescued victims associated with these incidents,” the minister told the lower house.

Of course, by then several other central ministries, a number of state governments, the Central Board of Secondary Education and even the Supreme Court had got involved, with the apex court calling the game a “national problem”.

But experts say official agencies may have jumped the gun. “It was definitely a hoax. We need to shift focus from these voyeuristic things and to suicides, which is a big problem that kills a quarter of a million people. Some of these hoaxes have a life of their own because media makes them into a big story. We need long-term institutional solutions,” said Soumitra Pathare, director of the Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy.

The biggest tragedy

Back in St Mary’s hill, Chandra Maya Sarki has gone back to her old routine — wake up at the crack of dawn to draw water, fix food for her husband before he leaves for his daily wage work, and then clean their small wooden house. She likes to keep the television on and stray dialogues from the afternoon soaps animate the living room. She stares not at the screen, however, but at the the small framed photo of Sarki hanging on the blue wall, wondering why the mysterious admins of the Momo Challenge chose her child as their prey.

She doesn’t know yet that the cyber cell of the West Bengal police has completed its forensic probe of his phone and found no trace of any Momo Challenge. “If any application is downloaded, the forensic machine would find a trace, even if it is an unknown application. But we have found no such application, or any message on WhatsApp motivating people to play the game. We have found nothing so far,” said a senior official of the cyber cell on the condition of anonymity.

She doesn’t know that police has ruled out any links between the game and the death of Aditi Goyal and that at least two other cases in the state have been found to be hoaxes traced back to mischief makers sending scary messages through WhatsApp. She doesn’t know that Sarki’s teacher Sarita Sharma has a simple explanation for why he and his friends would go to the graveyard at night — the mobile network was the best at that spot.

All she knows is that her beloved younger son will no longer come back home at 8pm every day. That she will never make him his favourite meal of dal-aloo and dum-eggs. The money she had been saving with her husband to send him to Bengaluru for higher studies now seems meaningless. Sometimes she talks to Sarki’s sister, now in college, about him and the day that took him away from her. She will probably never know what really happened to Sarki or what troubled him enough to withdraw from his friends. Momo Challenge or not, that is the biggest tragedy of all.

(With additional reporting from Ashiq Hussain in Srinagar and Manish Pathak in Mumbai)

By special arrangement with![]()