The Partition upheaval is a story of suffering on a vast scale. But embedded in the embers of violence are also golden nuggets of hope and victory of human enterprise. Narendra Nath Mohan, or NN, and his wife Ramrakhi Mohan were among the 18 million people who were displaced from their homes and had to desperately migrate to a new place. NN settled in the cantonment town of Kasauli and became a supplier to local British entrepreneur H.G. Meakin who ran beer distilleries and breweries in Kasauli and Solan.

NN soon created a place for himself in Kasauli. Despite the chilly winds and the cold, every Christmas — or ‘Bada Din’ as the festival is called in Hindi — NN would drive down to Meakins’ residence to personally wish him and gift a cake to his family, cementing a warm relationship with the brewer.

No surprise then that Meakin developed a soft spot for NN. In 1949, Meakin left for England but gave NN enough time to rustle up resources to purchase the Indian setup. And the latter rose to the occasion by starting a bold and unchartered chapter in entrepreneurship — a trademark of Partition survivors. “My grandmother had to sell off her jewellery and my grandfather had to take loans. But he managed to raise enough funds to travel to London where he acquired a majority stake in Dyer Meakin Breweries and renamed it Mohan Meakin,” says Vinay Mohan, the third-generation owner of Mohan Meakin.

Also read: Kim Brothers—Delhi’s Chinese shoe shop that dazzled Sanjay Gandhi, Arun Jaitley

Aiming for a large footprint

Today, after more than 70 years, it’s difficult to gauge whether NN realised he was making a promising purchase. The Kasauli brewery — the first in India — was established in the 1840s by Edward Abraham Dyer. It was also distinct for producing ‘Lion’, Asia’s first beer that became extremely popular in India among British administrators and troops. Lion started as a pale ale and remained the number one beer in the country for more than a century till the 1960s. In fact, even after its production eventually stopped in India, it continued to be locally produced in New Zealand and South Africa where the remaining British influence propelled its popularity. Such is the pull of this sticky brand that Lion is still the number one lager in neighbouring Sri Lanka where Mohan Meakin had introduced it in the1880s through its erstwhile Ceylon Bewery.

H.G Meakin bought the establishment from the Dyer family in 1887 and strengthened it by making it public at the London Stock Exchange. Meakin had also opened many more production centres in Ranikhet, Dalhousie, Chakrata, and Darjeeling, establishing a larger footprint in the country and increasing distribution. When Meakin sold the business to NN in 1949, it was a ready platform for NN to take off. And he did. He acquired large tracks of land in Ghaziabad and Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh and Khapoli in Maharashtra to build new production facilities. This played a big role in the creation of Mohan Meakin’s next big sticky brand – one that became the family’s identity and a calling card.

Also read: Prithviraj Kapoor to Kiara Advani—Delhi’s Delite Cinema remains a Bollywood favourite

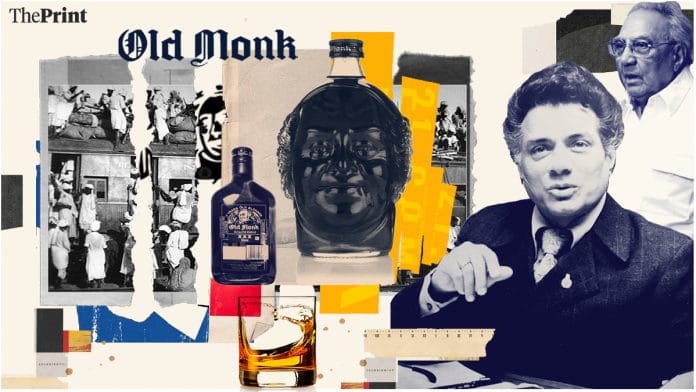

Old Monk, and the story behind it

Mohan Meakin’s Old Monk Rum was first prepared by Col. Ved Rattan Mohan, NN’s eldest son. Made from molasses and infused with a lingering taste of spices and vanilla, Old Monk is a dark rum that is matured in oak vats for seven years. Introduced in the 1960s, this rum soon became the largest-selling liquor brand in India. Even now, Old Monk remains the biggest Indian-made foreign liquor (IMFL) brand and sells in almost 30 countries across the world.

Although the design and shape of the bottle — especially the webbed impressions on the outside — were inspired by Old Parr, a popular blended Scotch whisky, the logo and the name were inspired by the drink brewed by Benedictine monks’ as they lead their ascetic life in the mountains. Everything, including the original bottle shape and the logo, has remained unchanged for the past six decades.

Ved Rattan Mohan and then his brother Brigadier Kapil Mohan never advertised Mohan Meakin because they believed that customer loyalty alone ought to carry the brand forward. And that is how it was from the 1960s onwards. Easy on the pocket, Old Monk acquired a reputation of being a ‘coming-of-age-drink’, something that college students and young adults could indulge in with their friends. Almost everyone has an anecdote or story around Old Monk. “Whenever I meet my old college friends for a reunion, it’s almost as if there are three people in the room—me, my friend, and the Monk,” says a nostalgic Arun Gupta, a diehard Old Monk loyalist.

Sticky brands are like old uncles who you love but you also pull jokes on them. With Old Monk’s easy, inexpensive and accessible image, there are a lot of jokes and memes about the brand. “If you want to know if an Old Monk bottle is real, turn the new bottle upside down. If it leaks, it’s real!” says Gupta, an Old Monk follower with a mischievous laugh.

The leaking cap yarn is of course not true but when you become a subject of memehood and good-hearted leg-pulling, you know you are a loved brand.

This article is a part of a series called BusinessHistories exploring iconic businesses in India that have endured tough times and changing markets. Read all articles here.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)