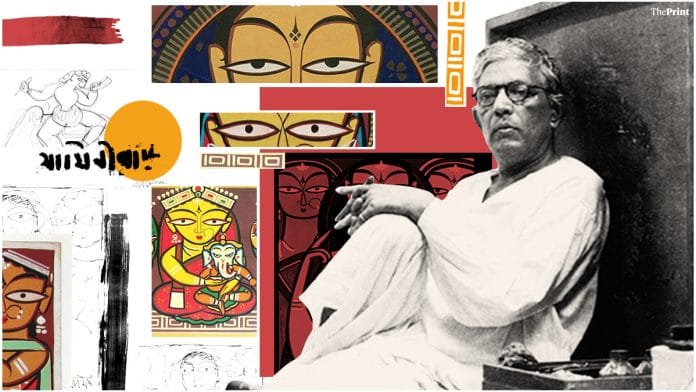

Famously known as the father of modern Indian art, Jamini Roy is the master behind those iconic folk style paintings with flat forms and bold outlines that many of us have seen. Ditching his academic training in Western art for a style inspired by Bengali folk traditions is what earned him a reputation in the late 1920s and early ’30s. The influence of the Kalighat Pat style is also believed to have lent him his signature artistic style.

As explained by author Krishna Chaitanya in A History of Indian Painting, Volume 2, “Roy produced a corpus which has not dated, continues to reveal hidden excellences to the modernist sensibility and has influenced modern art in India in several ways and at many levels.” In short, his art is both historic and immortal.

Roy was drawn to images of Santhals and simple village life. Though he championed the ordinary middle class, his works were adored by the rich and powerful, including former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi who ended up declaring him a “national artist”. He even had a reputation overseas, in cosmopolitan cities like London and New York where he held exhibitions.

In 1934, he was awarded the Viceroy’s gold medal and 20 years later, the Padma Bhushan. He passed away in Calcutta on 24 April 1972, at the age of 85, but the honours kept rolling in.

After his death, Indira Gandhi ordered that a section of his house be preserved as an art gallery and four years later, the Ministry of Culture declared him one of the “nine masters” whose work was considered to be a national treasure.

On Roy’s 48th death anniversary, ThePrint takes a look at how the artist discovered himself and his style, and how the concept of class seemed to penetrate every part of his life.

Also read: Raja Ravi Varma, the royal artist who became part of daily life through calendar art

Class-conscious painter who created new art idiom

Born on 11 April, 1887, Roy grew up in Belliatore — a village in Bankura, now in West Bengal. As a child, Roy would try to imitate the designs of carpenters, doll makers, potters and weavers in his village. Sometimes, he’d work closely with the village idol-maker which, according to Partha Mitter in his book The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-garde, 1922-47, is where Roy picked up a knack for bold and expressive contours.

At the age of 16, Roy attended the Calcutta School of Art where he was trained in Western art. Most biographies on Roy dismiss this part of his life since he eventually rejected his training to discover his own artistic style. But Chaitanya points out that Roy’s technical prowess in Western art is what enabled him to make a livelihood while starting out and his learnings in impressionism are reflected in later paintings.

By 1930, he had made a complete switch to traditional styles inspired by Patua scroll paintings and the Kalighat Pat style.

Roy, it is said, believed ordinary people were more important than governments in power and preferred to lead a simple life, right down to his paints. He opted for natural pigments from flowers, mud, chalk, “local rock dust mixed with the glue of tamarind seeds” or even the white of an egg, explains Chaitanya.

He reportedly never sold a painting for more than Rs 350 so that it would be affordable for those who were the focus of his art. But on gaining international recognition, Roy’s paintings ended up being sold upwards of $10,000, and sometimes, even for a fortune.

Take a look at the price tags that a British collector once slapped on three of Roy’s paintings — Christ with the Cross estimated at £8,000-£12,000, an untitled painting estimated at £6,000-£8,000 and Santal Drummers estimated at £8,000-£12,000.

Many say if the iconic artist were alive today, he would disapprove of the commercial value of his art.

Roy’s style has often been described as a “return” to folk style traditions or “a conscious and productive homegoing”, but it’s important to note that his paintings were more ingenious than indigenous. According to another Indian artist Mukul Dey, Roy’s line of art preserved a “typically Bengali” outlook but was an “improvement upon the traditional art of Bengal” that “open[ed] up a new field of art altogether”.

Also read: Enfant terrible of Indian art, F.N. Souza was not just a painter but also a brilliant writer