Kolkata: Filmmaker Krishnendu Bose was 10 years old in March 1971 when then Pakistan President Yahya Khan launched ‘Operation Searchlight’, a brutal military campaign that employed rape, torture, and murder to crush the East Pakistani uprising against West Pakistani hegemony over language, culture, and identity.

The resistance cry of the East Pakistanis back then was ‘Joy Bangla’, meaning Victory to Bengal, but young Bose had no idea of its significance. He thought everyone was talking about conjunctivitis, which many Bengalis also call ‘Joy Bangla’.

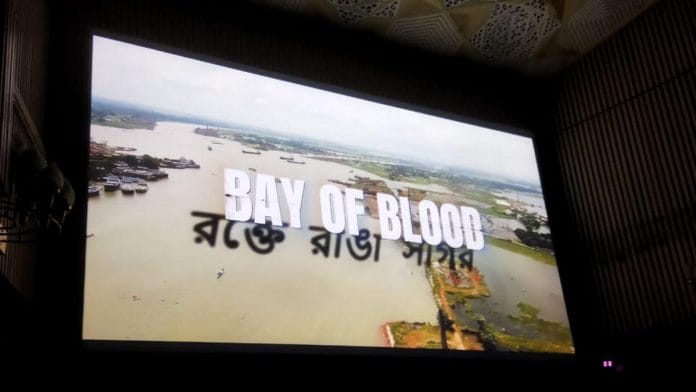

“I am a Ghoti (from the western part of Bengal, which did not bear the brunt of Partition) and grew up in Delhi. I thought Joy Bangla meant that eye disease. Much later I got to know it was the war cry that gave birth to the nation that we now know as Bangladesh,” Bose said at a special screening of his 95-minute documentary Bay of Blood at Kolkata’s Nandan cultural centre, organised by the Bangladesh Deputy High Commission on 14 June.

Released last year, Bay of Blood recounts Bangladesh’s bloody birth pangs in 1971 through a series of interviews with historians, war heroes, army defectors and rape survivors.

“It is not just me,” Bose added, reflecting on his childhood ignorance. “When we showed our film at Cannes, few knew about the genocide in East Pakistan.”

Going by the estimates of Bangladeshi authorities, around 3 million people were killed, hundreds of thousands of women were raped, and tens of millions were displaced during the 1971 war.

But Bay of Blood also doesn’t tell the full story of Operation Searchlight. It glosses over the massacres of minority Hindus by Yahya Khan’s army and paramilitary collaborators in East Pakistan—a tragedy that echoes even today with rising Islamic fundamentalism and ongoing attacks on minorities.

A sticker on a cricket bat & a song

Bay of Blood unpacks the horrors of 1971 through a series of interviews with those who know Bangladesh’s birth story intimately.

These include Salil Tripathi, author of a definitive work on that period, The Colonel Who Would Not Repent; retired Lt Col Quazi Sazzad Ali Zahir, who defected from the Pakistan army with strategic troop deployment maps and joined forces with India; and Meghna Guhathakurta, an academic and rights activist who witnessed her father’s murder by the Pakistan army as a young girl in Dhaka.

But of the most compelling stories is that of a sticker on a cricket bat that ignited a revolution.

On 26 February 1971, 18-year-old Raqibul Hasan, the only East Pakistani on the Pakistan cricket team, placed a sticker with the words ‘Joy Bangla’ on his bat. As he stepped out to bat at Dhaka’s Bangabandhu Stadium against the Commonwealth team, the crowd broke out in chants of Joy Bangla, overshadowing the four-day match.

The match itself was never completed. Demonstrations against Pakistan and in favour of a new nation for Bengali speakers erupted across Dhaka. And the young Hasan—who spoke at length in the documentary— traded his cricket bat for a Sten gun to fight for the liberation of his people.

And if a sticker on a cricket bat marked the beginning of a revolution, the documentary mentions how a song brought East Pakistan to the world’s attention.

It was at a dinner party in early 1971 that sitar maestro Ravi Shankar told his close friend George Harrison about the carnage across India’s border in the east. Shankar pulled out news articles and magazine cuttings to show his friend why his mind was in tatters. It made a big impact.

By the end of June 1971, Harrison got busy with organising a benefit concert to raise funds and let the world know about Bangladesh. The venue was New York’s iconic Madison Square Garden, and a star-studded lineup was put together to perform.

Shankar and Harrison insisted the concert was not political, but blame games began. Then US President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger were furious. “Goddamn Indians!” Nixon reportedly said in a private chat on funds pouring in for the concert.

On 1 August 1971, two concerts were held at Madison Square Garden. Performers included Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Alla Rakha, Kamla Chakravarty, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Billy Preston, Leon Russell, and the band Badfinger.

More than 40,000 people attended, and close to $250,000 was raised.

And the world knew about Bangladesh. But even now, a major part of the story remains largely in the shadows.

Also Read: History, heritage, hustle—Bengali filmmaker Prataya Saha’s 5-min movies on big cities go global

An inconvenient truth

The special screening of Bay of Blood in Kolkata, attended mostly by journalists, cinephiles, and history buffs, saw a few tense moments. Some members of the audience volleyed tough questions at director Krishnendu Bose.

“Is Bangladesh a secular country today, as you have mentioned in your documentary? one man asked. Another question quickly followed: “How are the Hindus in Bangladesh?”

Bose’s brief reply that there are “many perspectives” on an issue did not seem to satisfy the agitated members of the audience.

Bay of Blood is indeed economical with one aspect of the 1971 story: the selective massacres of the Hindus of East Pakistan.

In his 2013 book The Blood Telegram, American journalist and academic Gary J Bass quotes then-US Consul General in Dhaka, Archer Blood, to demonstrate that the Pakistani Army systematically targeted the Hindu community in East Pakistan while the Nixon Administration did nothing to stop it. But Bay of Blood does not address this in detail.

Another major element missing from the documentary is the role of Razakars and Al-Badr — paramilitary forces within East Pakistan that actively aided the marauding West Pakistani army in their campaign of rape and murder, especially against Hindus.

Last August, the death of Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, a Razakar and a convicted war criminal, brought hundreds of his mourning supporters out on the streets, exposing a schism in Bangladesh’s secular fabric. And continuing attacks on Hindus show the crisis in Bangladesh is far from over and Bay of Blood is ultimately an incomplete story, even if well told.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)