New Delhi: Maharaja Yeshwant Rao Holkar II was famous for two things. One was his brief but audacious attempt to declare independence for Indore instead of acceding to India in 1947. The second was his palace, Manik Bagh. Designed by the German architect Eckart Muthesius, this Art Deco marvel broke every rule of royal architecture, embracing sleek minimalism over colonial opulence. Nearly a century after it was conceptualised, an exhibition in Delhi is showcasing rare documents related to the iconic structure.

Titled ‘Eckart Muthesius and Manik Bagh – Pioneering Modernism in India’, the exhibition runs till 8 December at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA). It features vintage photographs, drawings, and watercolours that capture Manik Bagh as a “fairy tale palace” of Modernism.

“The sober design of the palace gave space for new ideas, for meditation,” said Raffael Dedo Gadebusch, head of the Asian Art Museum in Berlin, who collaborated with KNMA to curate the exhibition. “The huge banyan tree in the garden and the Mughal-inspired garden layout and waterworks are among the few subtle concessions to the Indian soul and tradition of the palace complex.”

Manik Bagh reimagined European modernism for an Indian context. Holkar, known for his fondness for art, luxury cars, and fashion, worked with Muthesius to weave Bauhaus aesthetics with traditional Indian elements, creating a seamless fusion of innovation and heritage.

The palace was completed in 1933, but in subsequent years too Muthesius played a role in interior design, overseeing every detail with care, from sculptures to furniture.

“United by their mutual passion, the two dreamers embarked on a journey to create a palace that would blur the lines between tradition and avant-garde design,” Gadebusch said.

Also Read: Narayani Gupta preserved Delhi history for decades. For scholars, she’s ‘God sent’

Europe to Indore

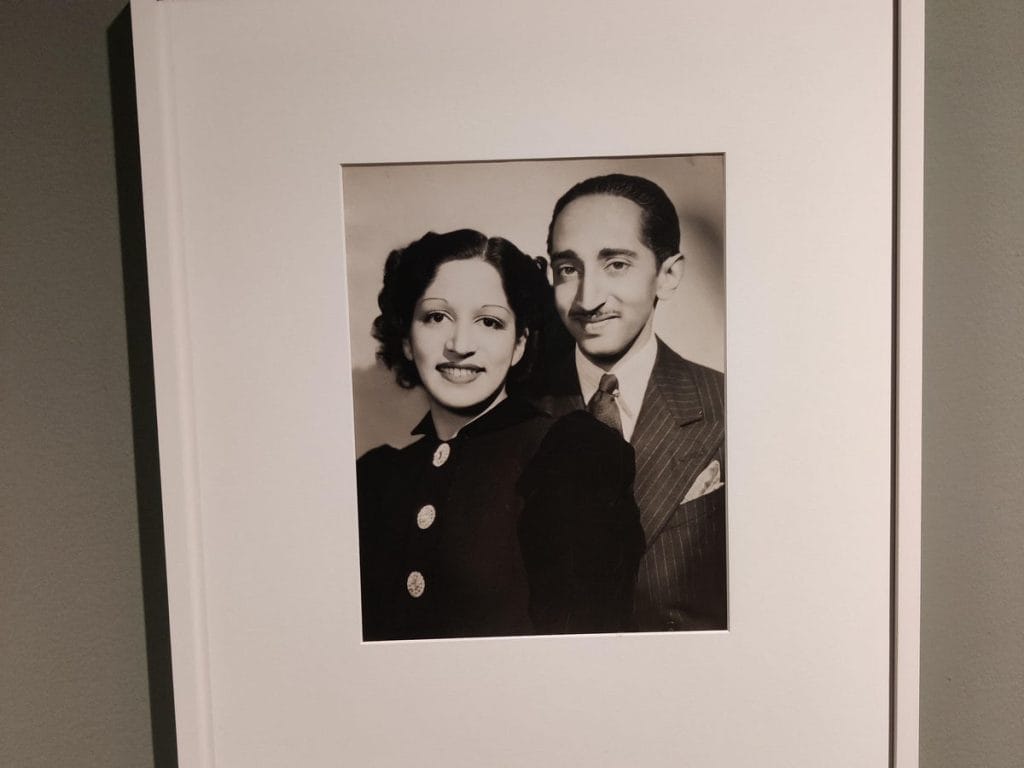

From their first meeting at an Oxford garden party to their travels across Europe’s capitals, Holkar and Muthesius took inspiration from the new and the bold. They mingled with art dealers, writers, designers, and artists such as Constantin Brancusi and Henri-Pierre Roché. Along the way, they also acquired modernist masterpieces, including Brancusi’s Bird in Space, which became a centrepiece of Manik Bagh.

The palace was a daring union of art, craft, and technology, marrying functionality with elegance.

“They redefined a royal residence, weaving a narrative that transcended continents and cultures,” said Gadebusch.

In a rarity for the times, the palace broke away from tradition in both design and many of the materials it used.

“Manik Bagh used artificial leathers and painted-grained glass instead of wallpaper,” said Gadebusch. The palace also had India’s first air-conditioning system, along with metal-framed and tinted windows, hydraulic doors, machined marble, and modern plumbing.

Yet, after 1933, the revival of classicism and baroque overshadowed Muthesius’s modernist vision. By the 1970s, Manik Bagh had faded into obscurity, its grandeur eroded by time. With Muthesius leaving during World War II and the Maharaja rarely living there, the palace was eventually taken over by the state, with its modernist legacy left without successors.

Today, the palace serves as a sarkari office—the headquarters of Indore’s Commissioner of Customs and Central Excise.

Also Read: What’s your image of Europeans in colonial Calcutta? Think beyond mansions & clubs

Breaking the rules

The modern aesthetic and forward-looking aesthetic of Manik Bagh reflected Maharaja Yeshwant Rao Holkar II’s “independent” and “cosmopolitan” outlook, according to Gadebusch.

The Maharaja—always ahead of his time—was also highly conscious of his image. While the palace was built with local bricks and wood, the practical pitched roofs, designed to handle Indore’s heavy monsoons, were so offensive to Holkar that early sketches depicted flat roofs instead. And they were even edited out of official photographs.

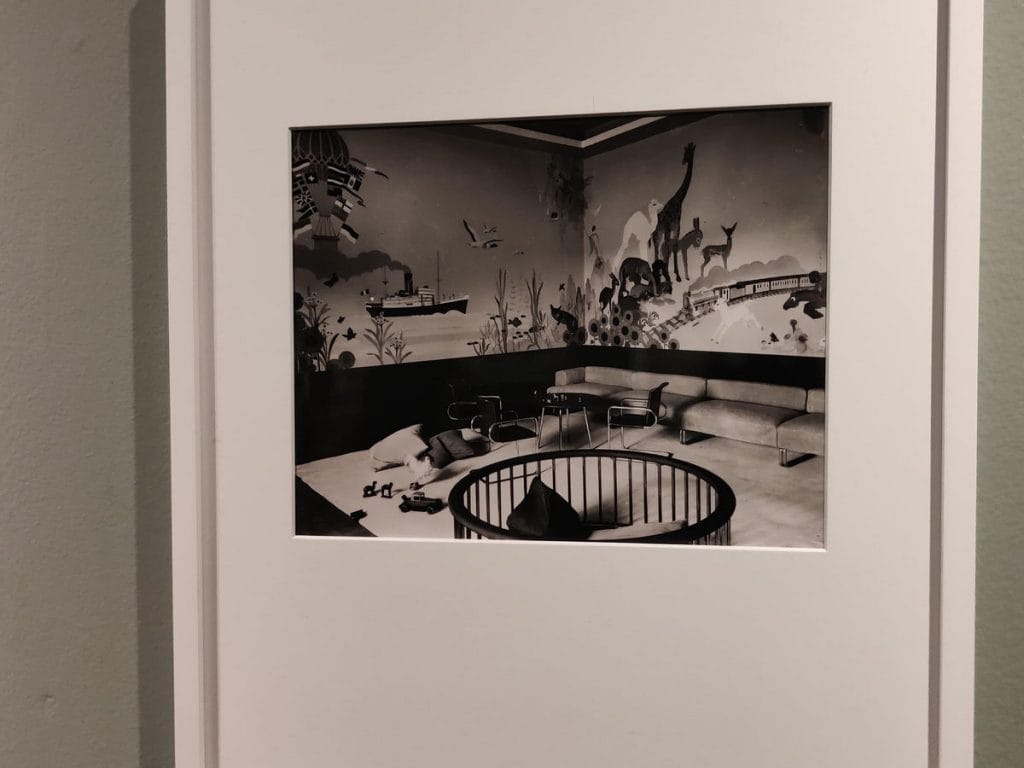

The Darbar (royal court) was a fresh take on traditional royal spaces. Its smooth, minimalistic design replaced ornate clutter with clean symmetry and openness. A muted palette complemented the Mughal-inspired garden outside, with its geometric layouts, running water, and a grand pond. Constantin Brancusi even designed a meditation temple for the palace, though it was never built.

The Holkars didn’t live there long. Yeshwant Rao Holkar’s wife, Maharani Sanyogita Devi, died in 1937 at just 22, and his enthusiasm for design faded. In 1980, many the palace’s furnishings—from leather chairs to animal-print chaise longues and glass bookshelves—were sold off at a Sotheby’s auction in Monaco, with French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent among the bidders.

Now, Manik Bagh’s avant-garde legacy survives only in its bones, design drawings, and photographs.

“It had tried breaking societal norms with every brick and Art Deco. The girl’s room in the palace could have been also for a boy. It stood as a political statement—modernity over colonial tradition,” Gadebusch said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)