New Delhi: “Can you please show me where he is one last time? I will leave after this,” requests the father of a 17-year-old who just got admitted to the Shashiraj deaddiction and rehabilitation centre in Delhi’s Shahdara.

Far away in Mumbai, the Aryan Khan-Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) fiasco continues to play out for hypnotised Indians. Aryan, the son of Bollywood actor Shah Rukh Khan, has been in judicial custody for 21 days since his arrest on 3 October without any recourse to bail, even as some argue whether an addict or a young person consuming illegal substance belongs in jail or in a care facility, and is to be treated as a criminal or a patient. But no one talks about what happens to an addict in India, beyond the 13-gram cocaine and 21-gram charas seized from the party ship headed to Goa, and endless judicial custody. The story of India’s rehab centres clearly isn’t as headline-worthy as Shah Rukh Khan. Or Sushant Singh Rajput.

Back in Shahdara, nothing short of a spectator, like those overseeing the debt-ridden players in Netflix’s Squid Game, the man in charge of the centre reluctantly grabs the mouse, enlarges the monitoring screen showing the dormitory and points to one boy standing in the faraway corner of the room.

“Woh raha woh (See, that’s him).”

The father takes a last glance at his son, Vaibhav. Still concerned, he then requests one of the patients coming out of the room to look out for his son in the private rehabilitation centre.

“See uncle, it will take some time for him to come clean. He won’t recover overnight. It will take around two months to treat him physically and another two months mentally,” explains Jai, who proudly admits to trying all kinds of drugs, “the best and the worst, from MDMA to cocaine to marijuana”. The Covid-induced quarantine exacerbated his addiction problems as it increased the distance between him and his father living abroad.

It isn’t a unique story. The Covid pandemic has been a double-edged sword. It pushed more and more Indians into addiction, with distress calls from drug users shooting up by 200 per cent during the lockdown, according to government data, but they didn’t have access to deaddiction centres, hospitals or even doctors. Most Indian families can’t accept addiction – alcohol, smoking, or drugs – in normal conditions. Imagine what the pandemic did to that.

“I resumed drinking (alcohol) and smoking weed. I needed an escape,” Jai, who is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts from the Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), says. Leaving the sobriety centre halfway before recovery, or just a month after he was admitted in June 2021, resulted in his first relapse. He now vows to stay as long as he is required to come clean. This is his third month.

“We did all sorts of pooja path, showed him to doctors, gave him medicines but nothing worked,” says Vaibhav’s father. His son had been trying to limit his alcohol consumption for four years but the pandemic and bad peers resulted in him consuming over 350 ml of alcohol per day.

However, instead of helping substance abusers overcome their addiction by sending them to detoxification and rehabilitation centres, the law enforcement approach has been ‘jail not bail’. According to many, the arrest of Shah Rukh Khan’s son Aryan Khan has laid bare how the NCB is not doing enough to stop the bigger fish in the pond – the distributors and makers, instead of the consumers and addicts. India needs better free rehab centres, counsellors, mental health professionals and past addicts as life coaches than young adults behind bars.

“If somebody is in possession of illegal drugs without a prescription or in excess quantity, we take legal actions against them. It is the job of the health and welfare department to rehabilitate addicts. Not ours. We do not conduct any counselling sessions when they are in our custody,” Sanjay Kumar Singh, Deputy Director General of NCB, told ThePrint.

Several police officers ThePrint spoke to also reiterated that they aren’t responsible and would not take an addict to a rehab centre until or unless they affect the law and order situation, or are in a critical condition.

Also read: Will Aryan Khan spend Diwali at home? Only Kashmir has taken TV news away from Mannat

Two worlds apart

Notwithstanding the chances of relapse in future, Delhi’s Jai and Vaibhav are privileged to have families who can afford to treat them at a centre where they get visited by a doctor and a physician daily, and a psychiatrist every week. But not all drug addicts meet a similar fate.

“With Aryan Khan’s arrest, the government is more into sending the message that if you engage in this behaviour, you will end up behind bars. But there is no mention of why and how they can prevent people from going in that direction. What is the approach that the government is taking on preventing drug use? How much resources are we allocating for rehabilitation?” asks Dr Yatan Pal Singh Balhara, additional professor of psychiatry, National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre (NDDTC), Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

Not all get accommodated at a centre with two giant television halls, two spacious bedrooms, one VIP bedroom and a gym at the roof, all for Rs 10,000 per month (Shahdara is one of the cheapest among other private centres in Delhi).

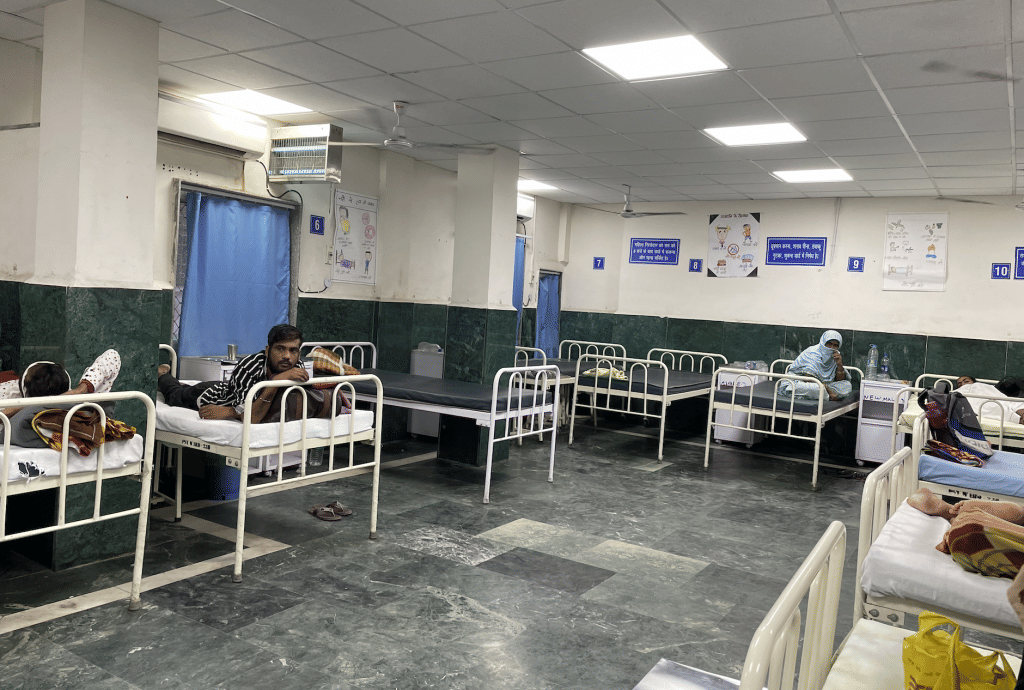

Almost an hour away is Ram Manohar Lohia (RML) Hospital’s mental health centre, where in ward number 23B is Imran’s mother who is having a hard time with her 30-year-old son. Still high on marijuana, Imran’s constant blabbering has annoyed everyone in the room. It took a guard to get him back to his bed.

This is one of the six deaddiction centres set up by the Delhi government in April 2016 for in-patient management of children and adolescents with drug/substance abuse. Only six out of the total 32 government hospitals had earmarked five beds for substance abusers that year. RML Hospital has increased the number of beds at the deaddiction ward to 20.

“He hasn’t eaten anything for the past 12 days and is suffering from low BP (blood pressure),” Imran’s mother, who has come from Gorakhpur, says, adding that the doctor had even put him on glucose. Imran has been taking marijuana or ganja for the past eight years and has been on and off medication for a few years, but hasn’t been able to stay clean.

In contrast to the regulations at the private centre, here in this crowded public hospital, a family member/attendant has to be with the patient at all times. Without one, a substance abuser cannot be detoxed.

“Most of these addicts are very violent when they are first admitted. It is difficult to control them. So, one of their family members has to be with them 24 hours,” nursing officer Ajay Meena tells ThePrint.

While the nursing officer claims that senior and junior resident doctors do a check every morning, the patient ThePrint spoke to told us that other than giving them their daily medicines, they were only made to do some exercise in the morning.

The permission to grant licences to private rehab centres is given by respective state governments under three different laws: The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, 1985; the Clinical Establishment Act (CEA), 2010; and the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. According to a report published by the National Centre for Biotechnology Information, only a few state governments have notified rules under the NDPS Act for licensing and regulation of “de-addiction” centres.

Also read: Aryan Khan is the second in Shah Rukh Khan family to be embroiled in a court case

Loneliness and joblessness

Not only do drug addicts in India meet two strikingly different fates once they vow to overcome their addiction, the coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns have also shown how the causes of their addiction are also distinct.

Vikram, a patient admitted at RML Hospital, and Jai, who is at Shashiraj Foundation, are both in their twenties. But that is the only thing they have in common. While Jai says he consumed drugs to find an escape from the absence of his father; Vikram, who plays dhol at wedding ceremonies and had quit doing ‘club’ drugs and ‘smacks’ (heroin) long back, says his inability to keep his family afloat during the Covid pandemic pulled him back into the drug trap.

“My son is an artist but this addiction has destroyed everything. He had sold off everything in our house. We may hardly have anything to eat at home but we will make him right,” says Vikram’s mother, who has just been handed over a list of medicines to buy for her son’s detoxification.

As Dr Vikash Singhal, who is a visiting psychiatrist to almost all of the private de-addiction centres in western Delhi pointed out, “Post-lockdown, those who were already substance abusers started doing more drugs, while those who had stopped, started having anxiety problems, and those psychologically disturbed by various incidents, were persuaded into doing drugs.”

Relationship problems within a troubled household have been a major factor in driving addictions during the pandemic, he said.

This was echoed by a team of psychiatrists and researchers in a paper published by the United States National Library of Medicine in May last year, which stated that the social and psychological implications of the pandemic can intensify drug abuse in a potentially catastrophic cycle.

While social distance, isolation or quarantine are essential measures to prevent coronavirus transmission, the paper, however, underlined that “these strategies, and the pandemic outbreak itself, have been associated with negative emotions, such as irritability, anxiety, fear, sadness, anger or boredom and are known to trigger relapse, even in those long-term abstainers, or intensify drug consumption”.

Also read: Does criminalisation curb drug consumption? What the use of NDPS Act in Mumbai tells us

Child and teen addicts

“We are already running out of beds to admit kids here. And also, there is a Covid protocol to follow. We are told to maintain only 60 per cent occupancy,” Arun Kumar, in-charge of SPYM (Society for Promotion of Youth and Masses) children deaddiction centre at Delhi Gate, responds to a phone call about the admission of a new child. It is only today that he has been able to pluck the courage to inform a member of Child Welfare Committee about the issues they are facing at the centre, he later admits.

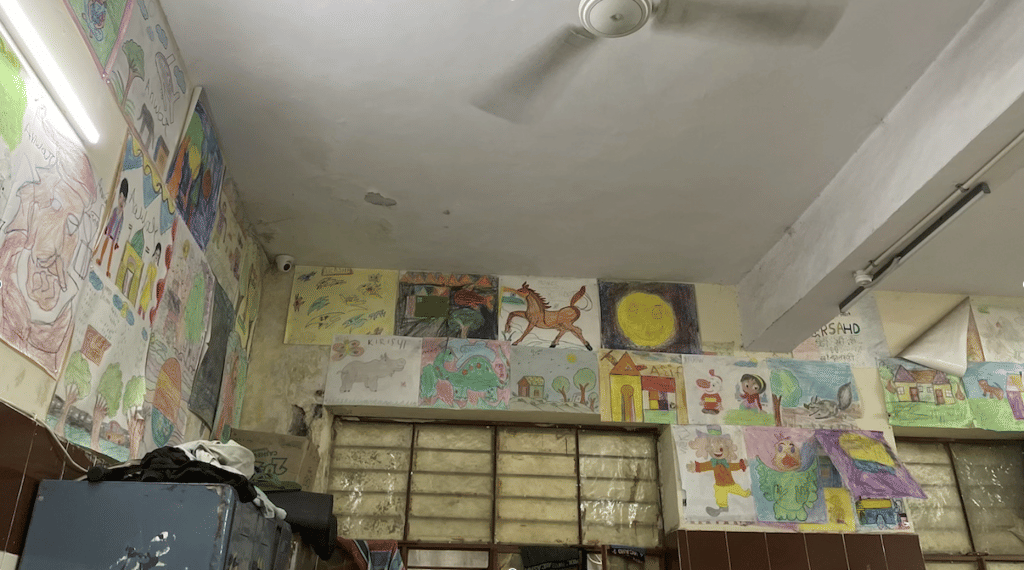

“But how can you say ‘no, we lack space’ and send such troubled kids back home. We are pushing them in the wrong circle. Pandemic has put us in a tricky spot” says Arun Kumar. The SPYM rehab centre has four halls –– one senior children’s bedroom, one junior children’s bedroom, and two activity halls, one of which is now an isolation ward.

Behind Arun Kumar, a whiteboard reads: Total number of children: 42, Volunteers: 2.

State-wise breakup below it says 35 children are from Delhi, six from Uttar Pradesh and one from Maharashtra.

Growing up in poverty, children below 18 indulge in various kinds of substances such as alcohol, inhalants, heroin, ganja and charas, among others, often due to bad company in their neighbourhood, and easy availability of drugs in the locality as their parents make ends meet.

While Kumar proudly shows an impressive collection of drawings from the children’s art therapy sessions, the posters haven’t quite buried the damp walls of the rooms.

If it wasn’t for the Covid pandemic, Deep Chand Bandhu Hospital in Ashok Vihar, New Delhi, would have detoxed at least 17 children in a month (as per their registrar). Sadly, the only hospital in Delhi that has a 30-bed deaddiction ward dedicated to juveniles (below 18) suffering from drug/substance abuse has been shut for over four months now due to the pandemic.

The facility didn’t resume even as coronavirus cases saw a sharp decline in the capital, mounting pressure on the NGOs that now face space and resource crunch to detox and rehabilitate the growing number of teens trapped into substance abuse.

“Covid pandemic has exposed the flaw in the system. Things got better way back but the hospitals are still not willing to admit these children for detox treatment,” says Kumar, who has been with the SPYM NGO for over two years now.

With many government hospitals out of the picture owing to Covid, poor families have now pinned their hopes on the two NGOs run by SPYM. One is SPYM children deaddiction centre at Delhi Gate, set up under the Child in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP) programme, and the other is Sewa Kutir at Kingsway Camp, for juveniles in conflict with law (JCL). The latter includes children who resort to petty crimes like pickpocketing, stealing and theft to fulfil their cravings.

Both these centres admit children after the referral of the state Child Welfare Committee.

These two NGOs are only equipped to rehabilitate children for three months to prevent relapses after the detoxification at government-run centres or government hospitals is completed. But with most of the deaddiction centres shutting doors on children and teens, the NGOs are now bearing the brunt.

The pandemic has also dented donations received by the SPYM from individuals, entrepreneurs and corporations. “The cause of helping treat drug addict kids has taken a back seat. They are more into helping people fight the virus now,” Kumar says.

Also read: Why India needs to re-look at messy drug laws, and not go for ‘Bollywood clean-up’

Experts on Covid impact on substance abuse

While the pandemic may have driven former and new drug addicts into taking these substances, according to experts, one of the root causes of the rampant drug abuse in India is the inaction of the government to curtail the availability of these illicit drugs.

“The government is not doing enough. Instead, the new excise policy will make alcohol available till late night. Addicts would be definitely tempted. It should be legally controlled,” Dr Singhal says.

Not only this, the lack of awareness about de-addiction centres at government hospitals plays a major role, as does the inadequate workforce at these centres. Following up with patients to prevent relapses is almost out of the question.

In the wake of Aryan Khan’s arrest during a “drug ring” bust on a cruise ship earlier this month, the central government has been thinking of making a fourth amendment to the Narcotic Drugs, 1985, and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act to empower the NCB to crack down on the trafficking of illicit drugs through the “dark web” or online drug trade and also make the home ministry the nodal administrative authority instead of the finance ministry.

However, the concern of undue “criminalisation” of consumption of drugs and the need to revisit penal provisions for those involved in drug use flagged by ministries and departments overseeing de-addiction and rehabilitation centres – Social Justice and Empowerment and Health and Family Welfare Ministry – has not been heeded.

While he refrained from speaking about Aryan Khan’s arrest saying the matter was subjudice, Dr Samir Parikh, Director, Department of Mental Health and Behavioural Sciences, Fortis hospital, reiterates the need to rethink such legislation. “Any person who suffers from substance abuse should be given all the treatment that we can but we should also have zero tolerance towards anybody who supplies people and takes lives away,” he says.

Quitting does not take long.

“If supported with medical treatment, most quit in 2-4 weeks. This is the short-term phase of treatment,” says Dr Balhara. But the real challenge is relapse prevention and rehabilitation, which takes months. “Around 60-70 per cent of substance abusers will relapse in a year if they don’t opt for long-term addiction treatment,” he says. A person must be trained to live a drug-free life, physically and mentally.

“We are overloaded, and are responsible for providing short-term detoxification treatment for a month or two. But the kids are again exposed to the same environment. NGOs should trace and track these kids,” says Dr Jyoti S. Kurian, senior resident, psychiatric department, Deep Chand Bandhu Hospital.

While the SPYM deaddiction centre says they try their best to follow-up cases by asking the parents to give updates, most don’t oblige.

“We have a team who calls the families of these kids and asks about their behavioural pattern. They have to bring their kids 15 days after getting discharged from here, but very few actually come,” Fazle Haque, who is in charge of tracking follow-up cases at SPYM deaddiction centre, says.

“They are a floating population. If they are here today, they are somewhere else tomorrow.”

Names of certain patients in rehabs have been changed to protect their identity.