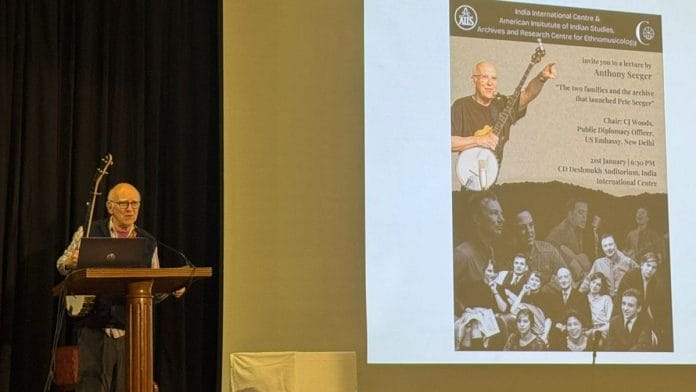

New Delhi: The audience at Delhi’s India International Centre erupted as Anthony ‘Tony’ Seeger picked up his banjo and launched into ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’ He urged everyone to sing along, just as his uncle, the legendary American folk singer Pete Seeger, often did.

With his banjo, Tony Seeger is keeping both his uncle’s music and folk legacy alive. An accomplished ethnomusicologist and archivist, he traced Pete Seeger’s musical roots to two families—the Seegers and Lomaxes—who crossed paths in the early 20th century and set the stage for the American folk revival movement.

Through archival audio recordings, he took the audience through the musical influences, institutions, and sounds that shaped Pete Seeger’s early years.

“This is also a presentation about archives, because archives change people’s lives,” Seeger said. “And this is an example of how archives started the career of Pete Seeger.”

The event, held on 24 January, opened with CJ Woods, public diplomacy officer at the US Embassy, sharing his excitement about being there with Tony Seeger.

“It’s about bringing people together through the power of music,” said Woods.

Also Read: Mir Taqi Mir sidelined for too long. His manuscripts being archived now

Cowboy songs and chance meetings

Long before Pete Seeger ever strummed a banjo, the Lomax and Seeger families were laying the groundwork for the revival of folk music in their own ways.

It all started with John Avery Lomax, who lived on a ranch in the late 1800s and was fascinated by cowboy songs. He spent years collecting them and was convinced of their cultural value. But when he shared his collection with his college professor, he was met with scorn.

“The professor said, ‘Oh, that’s terrible, worthless stuff. Study the great poets. Forget about cowboy songs. That night, Lomax was so hurt that he burned his manuscript,” Seeger said, as he moved on from a slide showing the Lomax family.

However, a few years later, when he was at Havard, his folklore professor said that it was great music, calling it American poetry on American life. The professor encouraged Lomax to publish a book.

“And Lomax went again and collected the music. He published a book called Cowboys in 1910,” laughed Seeger. The introduction of the book was written by former President Theodore Roosevelt—who also loved ranches and riding horses.

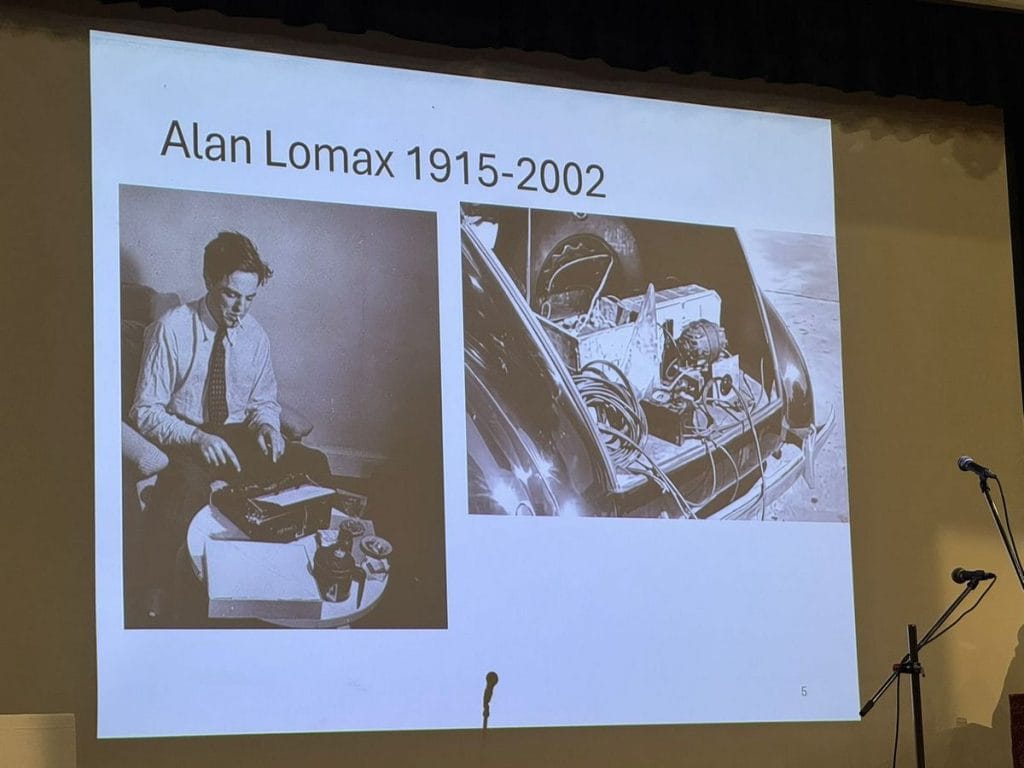

Lomax’s love for American music inspired his son Alan Lomax, who dropped out of Harvard at the age of 17 and joined his father in collecting songs.

Together, the Lomaxes travelled to prisons, museums, and rural communities, recording thousands of folk songs for the United States Library of Congress. Alan Lomax was eventually named Honorary Consultant for the Archive of American Folk Songs.

“It was difficult to collect music in those days and we didn’t have the recording devices that we have now,” Seeger said. “So they converted the back of a car into a recording studio. And if you wanted to learn a song, you didn’t go to YouTube—you bought books.”

Meanwhile, in 1921, Charles Seeger—Pete Seeger’s father—became the first professor of musicology at the University of California, Berkeley. But when he objected to the US entering World War I, the university’s president forced him into a year-long sabbatical.

And in that one year, Charles met composer Ruth Crawford, who would become his wife, as well as the Lomax family. Crawford helped the Lomax family transcribe their recordings.

“A contemporary once said that Charles Seeger and Alan Lomax provided the fuel, aimed him in a certain direction, and Pete took off like a rocket,” said Seeger.

Also Read: Lahore to Delhi & beyond—musical evening celebrates Punjabiyat through Sufi and folk songs

‘Hum Honge Kamyab’ connection

The Lomax-Seeger connection carried into the next generation as well.

At 16, Pete was hired as an assistant at the Library of Congress archive. He would visit the archive, listen to the recordings, and write them down for the archive’s director—Alan Lomax.

“That’s how he was exposed to old music, the vernacular music, the music of people in the hills and valleys who were working hard at various occupations. And that’s what Pete became,” said Seeger.

As Pete became successful, many people questioned his choice of instrument—the banjo. Tony Seeger recalled his uncle’s response in an interview: “It’s probably impossible to say in words why one person likes one instrument and another person likes another. I can remember as a 13-year-old being tremendously attracted to the sound of the banjo.”

Tony Seeger described his uncle’s music as a “real homage to traditional styles of that time.”

As the event drew to a close, several people in the audience requested Seeger to sing We Shall Overcome—an old gospel song popularised by Pete Seeger and which became an anthem of the American civil rights movement. Before he began, Woods shared a personal memory.

“As an African-American kid, Pete introduced me to We Shall Overcome, not We Will Overcome,” Woods said, drawing a huge round of applause. The song had started as ‘I’ll Overcome’ before African-American activist Lucille Simmons changed it to ‘We Will Overcome’. Pete Seeger later adapted it, crediting the final wording to his “Harvard education.”

The evening ended with everyone standing to sing the song—first in English and then in Hindi: “Hum Honge Kamyab Ek Din.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)